la sed

EDEN ROAD

martin kessler

The story is simple enough. During a time of war, a battalion of soldiers are in dire need of

water. A convoy of water trucks and their brave drivers are sent to relieve the battalion.

Gradually the convoy is whittled down by misadventure through the perilous terrain until there

is just one truck left, with a hero and heroine determined to bring its precious cargo to its final

destination. They will certainly never return, and perhaps not even arrive at all.

Hijo de Hombre (Son of Man) is our destination, but I want to take the winding scenic route,

with the occasional detour. The film stands on its own, however I want to add what context I

can to it. Nothing hurries me, and nothing halts me.

HiJO DE HOMBRE / LA SED

lucas demare, 1961.

CiNE ARGENTiNO

~ artwork by patrick horvath ~

~ special thanks to ana orsatti ~

~ written by martin kessler ~

My interest in the history of Argentine cinema is only very recent, and just a few years ago was

familiar with just a handful of Argentine films and filmmakers (like Luis Puenzo for instance). I

can attribute much of my new fascination to the one-two-punch of seeing Lisandro Alonso’s

film Jauja (2015) followed by Lucrecia Martel’s film Zama (2017). I was captivated by the pair of

poetic period films. They place their protagonists in direct opposition to landscapes as

beautiful as they are overbearing, evoking themes ranging from the colonial to the existential.

Their filmmakers are associated with the New Argentine Cinema, which emerged in the 1990s,

but for this piece I’ll be looking back at an earlier age of Argentine cinema. Without getting too

in-depth, I think it’s worth touching on the cinematic ecosystem that Hijo de Hombre emerged

from.

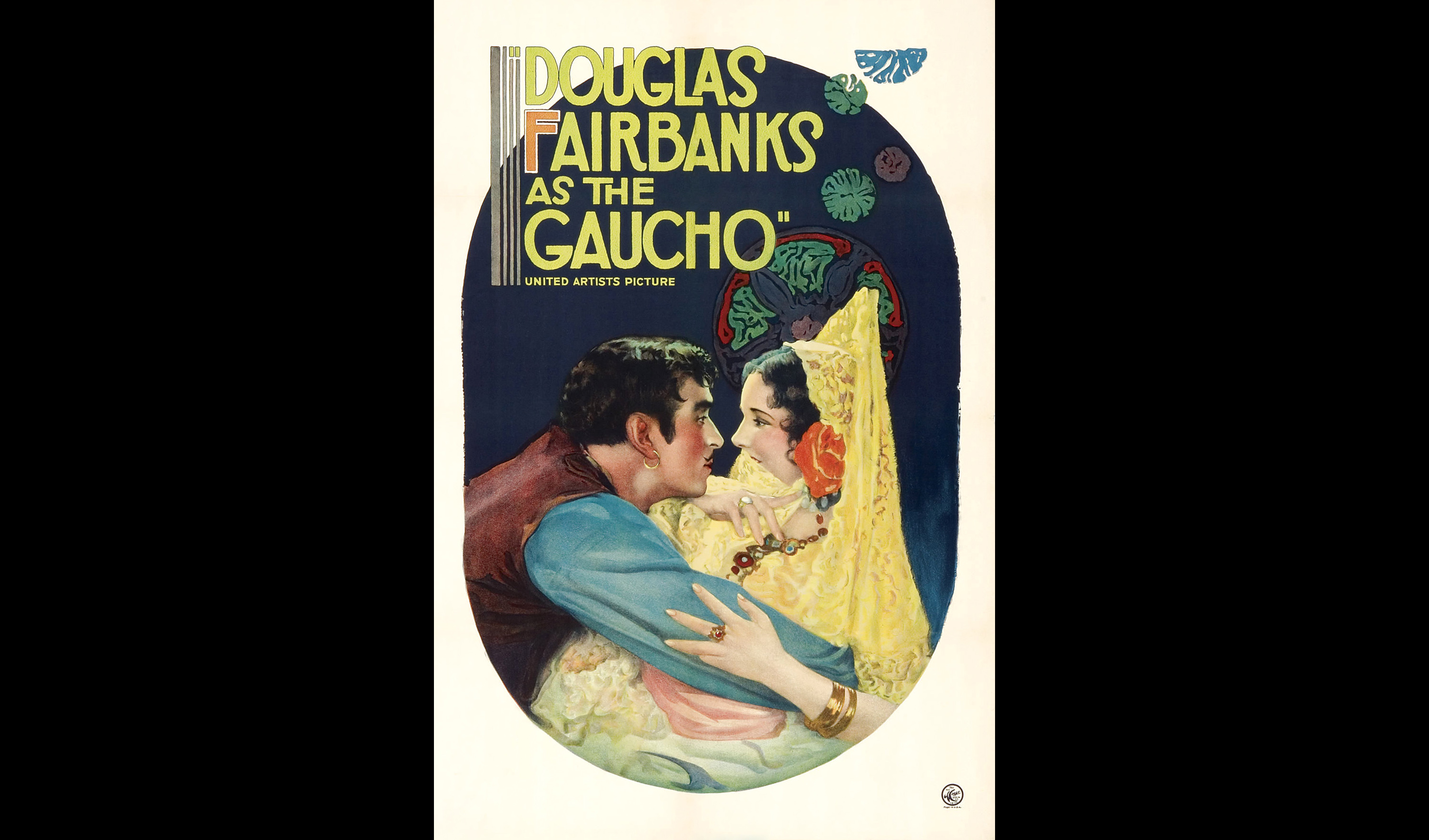

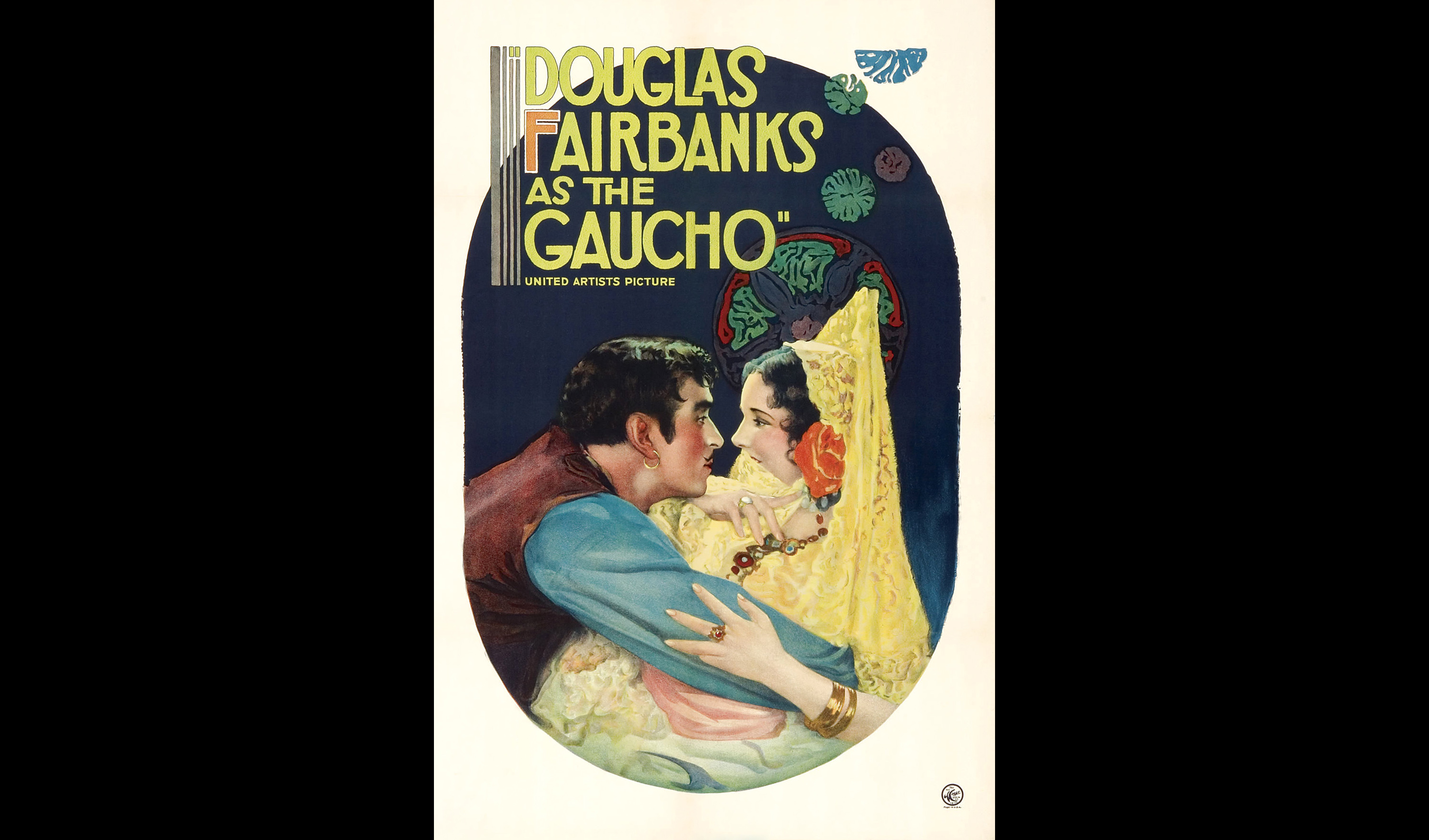

During the silent era, Argentine movie theatres were largely filled with import from Hollywood

and Europe. Argentine heroes were played on the big screen by American actors, like Douglas

Fairbanks in The Gaucho (1927).

There were of course silent Argentine films (Nobleza Gaucha being a much-celebrated early

example), but the introduction of sound allowed Argentine cinema to flourish. With sound

Argentine audiences could hear movies in their own Rioplatense dialect. It ushered in what’s

generally referred to as ‘The Golden Age of Argentine Cinema’. The industry grew rapidly, and

during its peak was the most productive and lucrative film industry in Latin America. For

instance in 1942, there were 56 feature films produced in Argentina, eclipsing Mexico’s 42.

An advertisement for the Libertad Lamarque vehicle Tango! (1933), the first Argentine film to

use optical sound:

It wasn’t always steady going, and there were dips in production during The Golden Age. The

largest one came during the latter half of the Second World War. A U.S. embargo on the

country included raw film stock, which ground the Argentine film industry to nearly a halt. The

main American rational was to prevent the officially neutral, but Axis-friendly nation from

potentially producing pro-fascist propaganda films. Set visits during the war from high ranking

Nazi propagandists isn’t exactly a good look. Another motivating factor was the conscious

push for the American film industry to have a greater foothold in Latin America, apparently a

market that often resisted the export of Hollywood films. I guess it shouldn’t be surprising that

American meddling in Latin American affairs would extended to film. A product of that initiative

was one of Orson Welles’ many never-completed films, It’s All True, shot in Brazil while The

Magnificent Ambersons (1942) was being butchered back in Hollywood.

From left to right: Argentine film director Alberto de Zavalía, Argentine actress Libertad

Lamarque, the wife of the American ambassador to Argentina, and Orson Welles:

Still, the Argentine film industry rebounded after the war and continued strong - for a little

while, at least. Eventually it settled into a gradual decline due to a faltering economy. Hijo de

Hombre, the film I’m building up to, was released in 1961, which would put it at the very tail

end of the era.

I was disappointed to find how little was written in English about the films of that remarkable

golden epoch, with a number of critics and scholars in the 1980s and onwards writing off the

entire period for being too bourgeois and full of sterile aestheticism. Instead many of them

favour the socialist realist films that began cropping up in the 1960s, focused on poverty and

misery. I have nothing at all against those films, but it’s a clear trend of North American and

European film critics being enamoured with them. Some view those films as being in artistic

opposition to the sorts of movies that marked the Golden Age of Argentine cinema. Others

don’t acknowledge that there was anything before at all, as if South American cinema simply

didn’t produce anything worth mentioning at all before Cinema Novo (the Brazilian new wave). I

mean, I kind of get it... movies about love triangles and the Tango seem frivolous when put

next to something like Brazilian filmmaker Nelson Pereira dos Santos’ Vidas Secas (1963), a

Naked Island-esque masterpiece about a poor family forced to kill their beloved dog to avoid

starvation.

Nonetheless, I think devaluing an entire era of filmmaking is their loss. I’m sure Argentina had

its share of out-of-touch “white telephone” movies, just as film professor Tim Barnard points

out in Popular Cinema and Populist Politics (linking them to the semi-propagandistic Italian films of the Fascist era), but watching a

number of the films for myself paints a different picture. Classic Argentine cinema is full of

imagination and exuberance; tragic romance stories, great gaucho western epics, elaborate

tango musicals, hardboiled crime stories, crowd-pleasing sports dramas, stylish horror stories,

and melodramas with a flair for the erotic. Watching several in a row, I’m overwhelmed by the cinematic resplendency of it all. I feel a little like Salvatore at the end of

Cinema Paradiso… or if I wanted to use a specifically Argentine example instead, there’s a

similar scene in Leopoldo Torre Nilsson’s The House of the Angel (1957) where the main

character Ana goes to the cinema.

Films were a point of pride for the nation. The prominent Argentine film critic, Domingo Di

Núbila describes Argentine cinema of that time as “national, but not nationalistic”. The films

made a point of asserting Argentina’s independence on the big screen without treading into

jingoistic territory. It might be worth reminding people who haven’t seen the Madonna musical

lately, that Argentina’s most famous first lady, Eva Perón (formerly Eva Duarte) was an actress,

though the more I actually see of her acting the less I’m convinced that she had any

appreciable acting talent whatsoever. There are also persistent rumours of her using her

political influence to have certain actors blacklisted, but forget I even mentioned that.

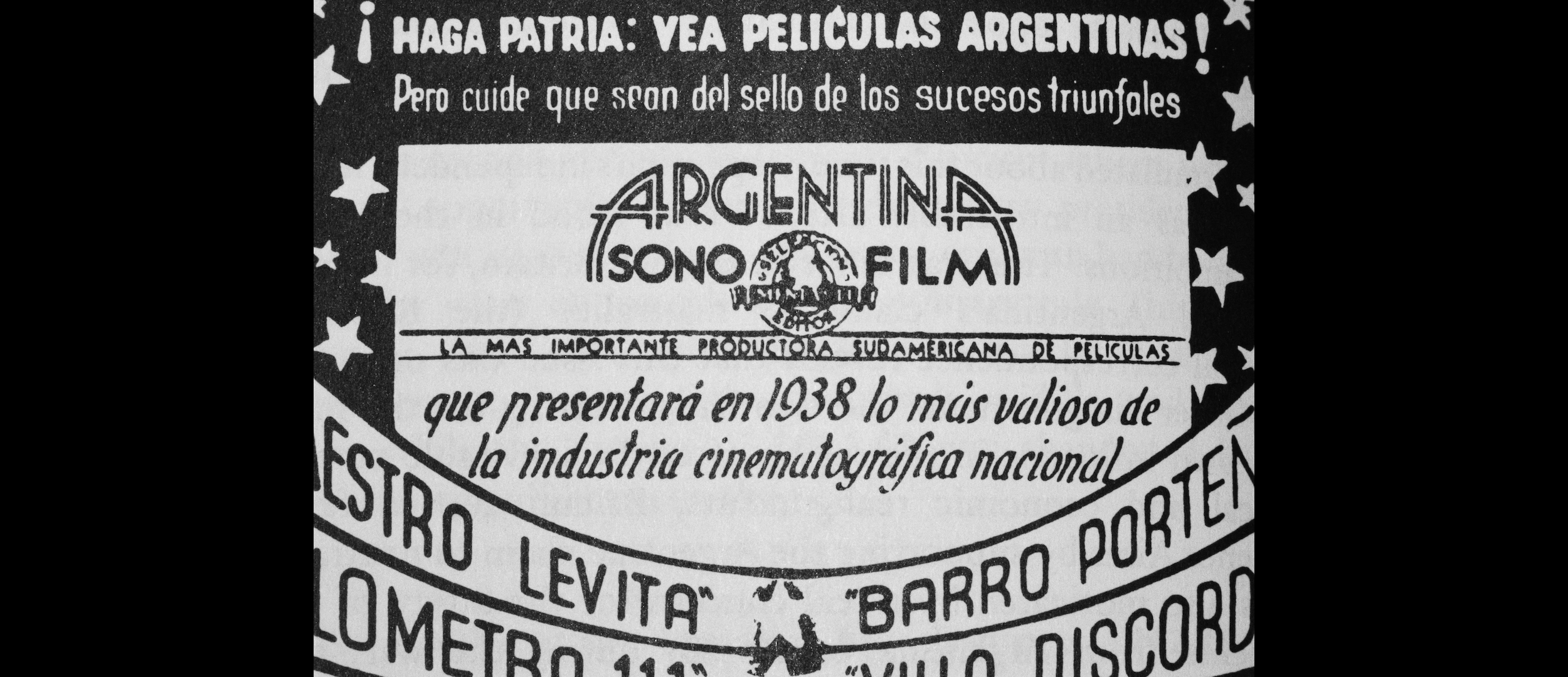

A 1938 Argentina Sono Film studio publicity ad proclaiming “Be Patriotic! See Argentine

Movies!”:

Regardless of the patriotic tenor around classic Argentine cinema, the films themselves have a

decidedly international flavour to them. I know there’s at least the stereotype of Argentines

thinking of themselves as ‘more European’ than other citizens of South American nations. At a

Q&A following a screening of Zama that I attended at the New York Film Festival, director

Lucrecia Martel suggested that perhaps Argentines don’t think of themselves as a part of Latin

America, and instead fit in somewhere between ‘Paris and Florida’. I took the implication of her

statement to mean a sort of blend of high culture with sweaty vulgarity. With my stumbling

through classic Argentine cinema, I get at least an impression of what she may have been

describing, with films that are examples of both an effort to imitate and compete with the

polished output of classic Hollywood, while also being clearly influenced by the poetic realism

and neo-realism of European cinema. The blending of the two is less awkward then the

unacquainted might expect. For instance one film I watched recently was the outstanding 1953

soccer melodrama, El Hijo del Crack (1953). It starred Argentine actor/producer Armando Bó,

and was directed by Leopoldo Torre Nilsson and his father Leopoldo Torres Ríos (the younger

of which would become more prominent the following decade). It comes across a little like

splitting the difference between Knute Rockne, All American and Bicycle Thieves.

International influence on Argentine cinema wasn’t limited to the stylistic either. Exploring

Argentine cinema, I’d often run across films based on works by international authors including

Tolstoy, Wilde, Chekov, Ibsen, Flaubert and Schnitzler. Apparently in an effort to counter-act

that, in 1947 General Perón legislated that a minimum of ten percent of all films had to be

based on Argentine stories. While Hijo de Hombre is an Argentine film production, it’s neither

Argentine in its subject nor its origin.

THAT MAN FROM PARAGUAY

The film is based on a novel by Paraguayan author and poet, Augusto Roa Bastos. In addition

to writing in Spanish, Roa Bastos would often include words and phrases in Guarani, (a widely

spoken language of Paraguay’s indigenous population) which Roa Bastos had learned in his

youth growing up on a rural sugar plantation. He had written poetry and short stories leading

up to it, but Hijo de Hombre was his first novel.1 Roa Bastos said that he had originally set out

to write Hijo de Hombre as a short story, but failed when its scope spiralled into something

larger. The novel is really a collection of nine stories (bumped up to ten with Roa Bastos’

revised 1982 edition of the book).

The stories have some overlapping or related characters,

and blend religious allegory (often ironically) with realism informed by Roa Bastos’ own

observations and experiences. They take place in Paraguay and span from about 1910 to

1936. That includes the war the film is set during, The Chaco War (1932 - 1935).

The Chaco War is also known as The War of Thirst, and it was between Paraguay and

Bolivia.2 Those nations fought for control over the Chaco Boreal; an inhospitably dry lowland

where thirst proved to be as deadly as bullets.

In the film, one soldier begs to be able to drink

the piss of his companion, just to alleviate his thirst. The novel further elaborates:

We have lost all hope that the water trucks will come, and all hope of escaping from this

clearing, which we have gone through much effort to defend. The strongest of us could not

walk a hundred paces without collapsing. The air has evaporated the last drops of our sweat,

and even dried up our tear ducts. Anyone who has managed to keep some urine in his bladder

can consider himself lucky. There is brisk traffic in that liquor... Only a miracle can save us. But

in this accursed Eden, no miracle is possible.

One of the reasons most often pointed to for why that mercilessly dry region was fought over

was because it was believed then, that it was home to massive oil reserves. The situation was

exasperated by the interests of the U.S.-based Standard Oil Company, the company that

would inspire the fictional/satirical SOC, Southern Oil Company in Henri-Georges Clouzot’s

doomed trucker classic, The Wages of Fear (1953). Time would reveal that there was no oil to

be found there.

Augusto Roa Bastos had experienced The Chaco War firsthand as a stretcher bearer and

auxiliary medic, joining up when he was only fifteen years old. His experience with the

wounded and the dead left him to wonder, "why two brother countries like Bolivia and

Paraguay were massacring each other”. That experience was formative in his pacifist outlook,

and his austere (bleak even) humanism. It would only be reinforced by his time spent as a war

corespondent in France during the second World War.

Yet another war, The Paraguayan Civil War, caused Roa Bastos to flee to Argentina. There his

writing and his criticism of Paraguan dictator, General Alfredo Stroessner, would eventually

earn him the label of “subversive figure” back in his home country and ensure his exile for the

next four decades. Hijo de Hombre would be taught in Paraguayan schools before Roa Bastos

was permitted to return to his homeland.

After relocating to Buenos Aires, Roa Bastos had several odd jobs to get by, including work as

an insurance salesman and as a radio host. He had an affinity for film, and his skill with words

eventually managed to find him some work as a screenwriter. The first movie he’d write was the

provocative Thunder Among The Leaves (1957), which he adapted from one of his own short

stories that would be collected in a book also called Thunder Among The Leaves. The film was

a vehicle for actor/producer, and now director, Armando Bó, who seems to have made it his

goal to act with his shirt off for as much of the film as possible.3 It’s noteworthy for kicking off

the twenty film-long collaboration with Bó and his muse (and purportedly mistress), actress

Isabel Sarli.

Thunder Among The Leaves is a very good film, full of stark imagery and poignant subtext, but

it also foreshadows the sexploitative direction that Bó and Sarli’s movies together would

gradually take. The film was heavily influenced by ...And God Created Woman (1956), and there

seems to have been a conscious effort to market Sarli as Argentina’s very own Brigitte Bardot-like

sexpot. The most famous scene in the film is of Sarli bathing nude. A lack of formal

censorship in Argentina allowed for that sort of artistically daring content, which would have

been prohibited in many other countries at the time. The bathing scene was controversial, but

almost certainly played a role in the film’s success, with Thunder Among The Leaves being the

most financially successful Argentine film ever made at that point in time.

Roa Bastos would write a follow-up film for Armando Bó & Isabel Sarli, titled Sabaleros (1959).

It would feature even more scenes of Sarli bathing in the nude and bare-chested Bó, and

would also prove successful (both commercially and critically), but after that Roa Bastos would

part ways with the movie star duo, and move on to other film projects.

Roa Bastos’ screenwriting career would eventually culminate in Hijo de Hombre. He, himself

would write the screenplay for Hijo de Hombre. In adapting his novel to the screen, Roa Bastos

selected two chapters, entitled "Destined" and "Mission." Most sources refer to the film as an

adaptation of Mission exclusively, though in reading the novel it’s clear that elements from the

preceding chapter Destined were incorporated into the film. At first the stories in each chapter

seem very different. For instance "Destined" is told in the first person, while "Mission" is told in the

third person. However, in reading them back to back, it becomes clear that they are parallel

stories that connect by the end.

The story of "Destined" is about a man who finds himself in command of a battalion of soldiers,

who he ultimately sees die slowly and horribly of thirst. It ends with him losing his mind and

tempting death by firing his machine gun at a truck that appears. The story of Mission is about

a driver and a nurse who are part of a dwindling convoy of water trucks sent to relieve a

battalion of soldiers. The drivers are called “aguateros”, referring to the ancient profession of

water-bringers, often depicted carrying jugs of water on their back. It isn’t until you reach the

end of "Mission," and the hero is tragically machine-gunned to death, that you realize the shooter

was the delirious-with-thirst protagonist of Destined!

Don’t worry, I’m not slapping you with the end of the film right away. That parallel narrative

structure from the novel was jettisoned for the film in favour of something a little more

conventional. It doesn’t conclude with the main character being murdered by one of the men

he tried to save. The film’s ending isn’t upbeat or lacking in depth either though. I’ll get to the

ending when it’s more appropriate (like near the end of the article), but I just want to give some

sense of the material that the filmmakers were working from.

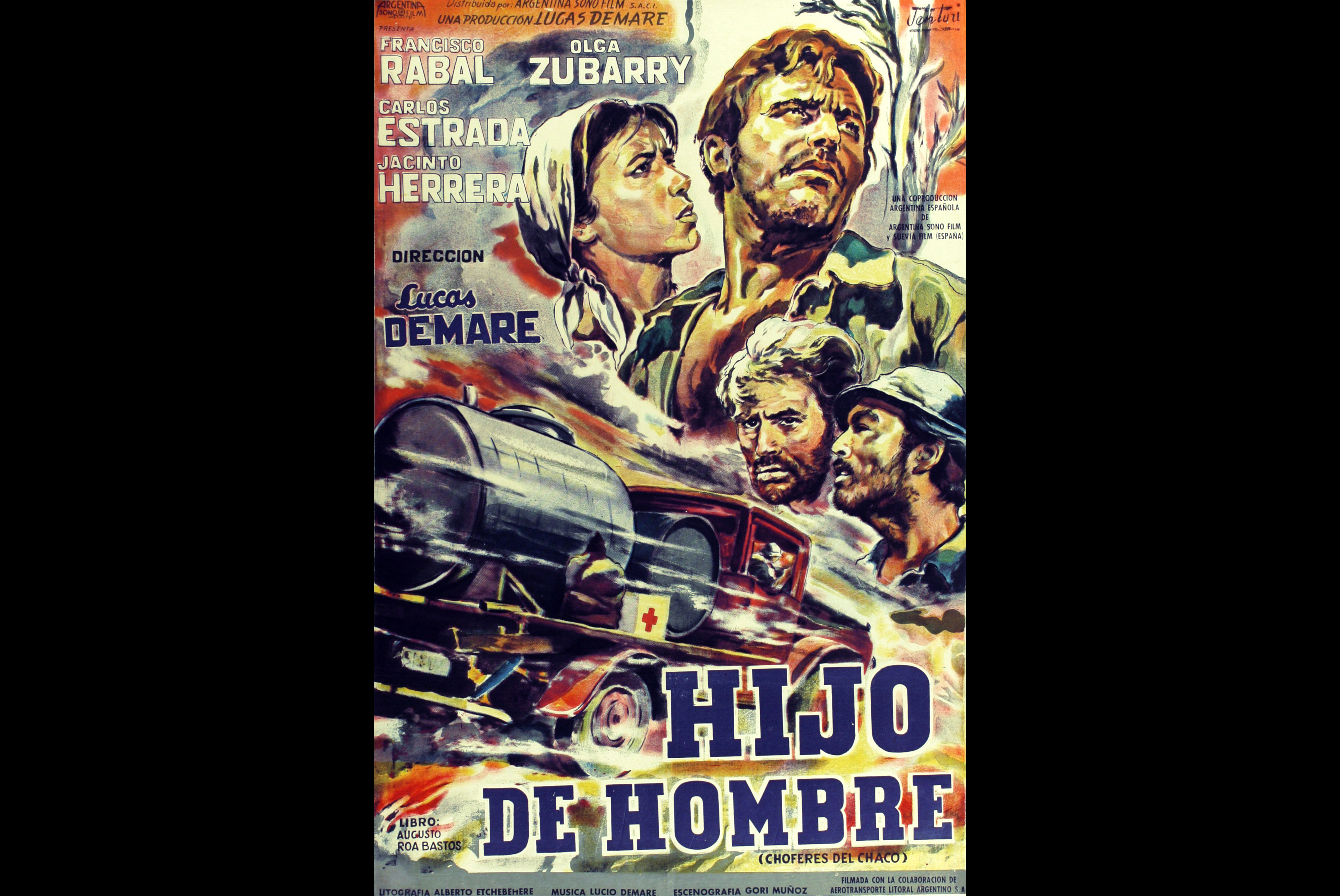

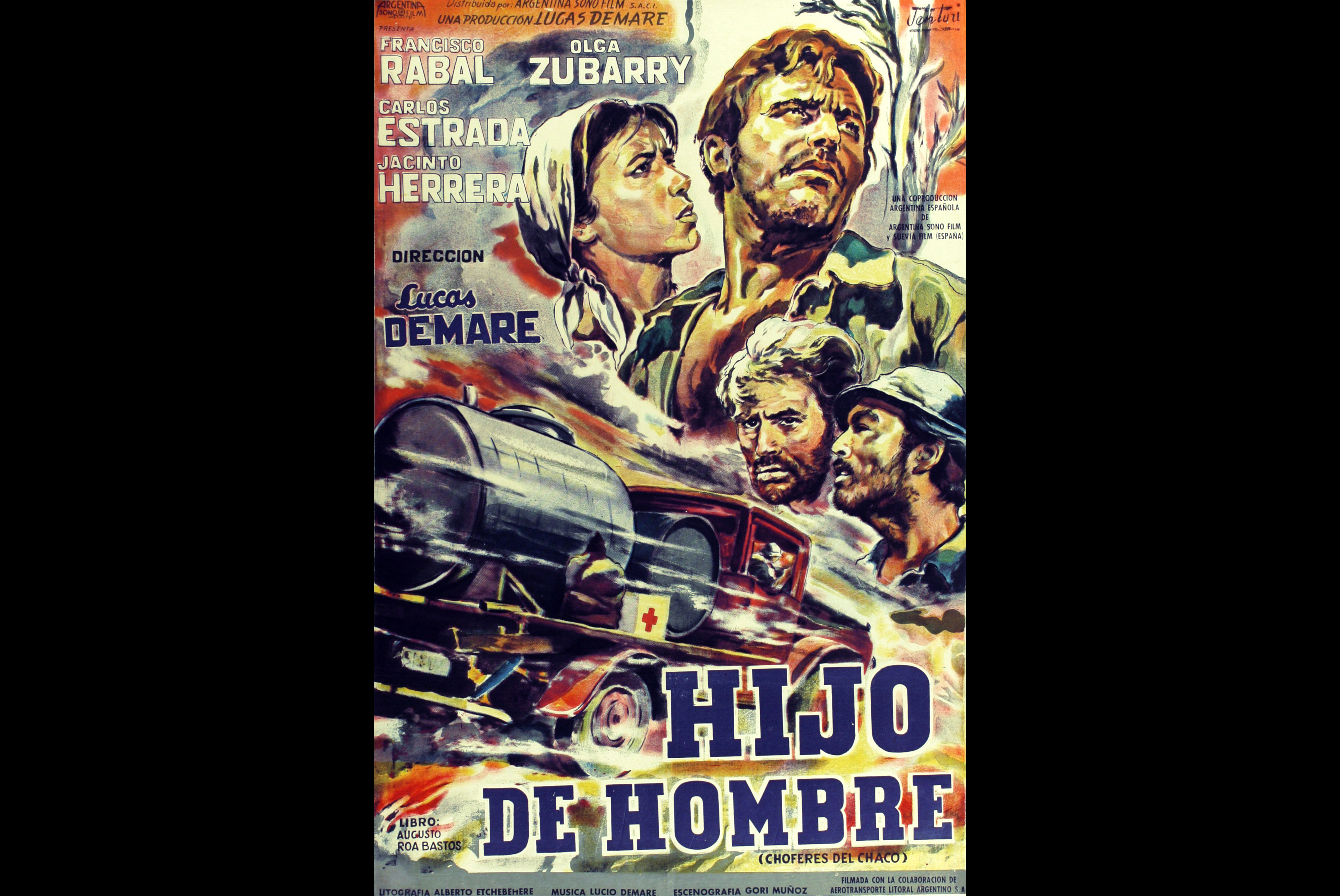

The paring down of the book’s stories is likely why the film and its accompanying posters

feature a bracketed “Choferes del Chaco” in smaller text under the tile. Meaning “Drivers of

Chaco”, it likely would have communicated to audiences familiar with the book, that the film

only intended to focus on just 'that story about the truck drivers’, rather than be some

sprawling saga that tried to incorporate everything.

While I’m discussing titles, I should explain why the film also goes by the title of La Sed (The

Thirst)...

Actually, not only does it have multiple titles, but multiple versions. La Sed was the European

release title, and despite being the more widely seen version of the film (with other European

releases using it as their basis), it’s also generally considered the inferior version. La Sed is

about two minutes shorter than the Argentine cut, mostly excising some sexually provocative

moments that would have been unwelcome in Franco’s Spain. It’s less drastic than the 35-

minutes or so cut from The Wages of Fear for its American release, but still a hinderance.

Even more noticeable were the changes made to the film’s audio. The film’s dialogue was dubbed

over to eliminate the dialects of the original cast, out of concern that they were too difficult for

audiences in Spain to understand. Two Spanish writers, Emilio Canda and Antonio Cuevas

(who later abandoned writing altogether to become a successful producer) wrote the

translation, and there’s a consensus that the poetry of Roa Bastos’ dialogue was lost.

Fortunately, Roa Bastos’ dark poetry can still be found in any version, because it was woven

into the visuals of the film by its director.

HORSEPOWER

Direction of Hijo de Hombre fell on the sturdy shoulders of Lucas Demare. It was made towards

the end of his most productive period as a filmmaker which began in the late 1930s and

slowed down toward the end of the 1950s, not coincidentally overlapping with The Golden Age

of Argentine Cinema. He had a reputation as a true workhorse, and directed forty films (thirtyfive

of them feature-length) over the course of his career, covering a wide variety of genres

including musicals, melodramas, adventure stories, and westerns (the most famous of which,

Savage Pampas would be remade in English). He was intelligent and worldly, but unpretentious

and well known for his ‘common touch’. He said that he preferred to direct while dressed only

in “shorts and short boots”, and it’s not uncommon to see behind the scenes photos of him

directing on location shirtless with a viewfinder hanging from his neck.

Lucas Demare was born in Buenos Aires, and had initially been trained as a musician, playing

the bandoneon (a type of concertina), in the prestigious Tango Orchestra of Argentina, which

his famous older brother Lucio Demare would eventually be a conductor and composer for.

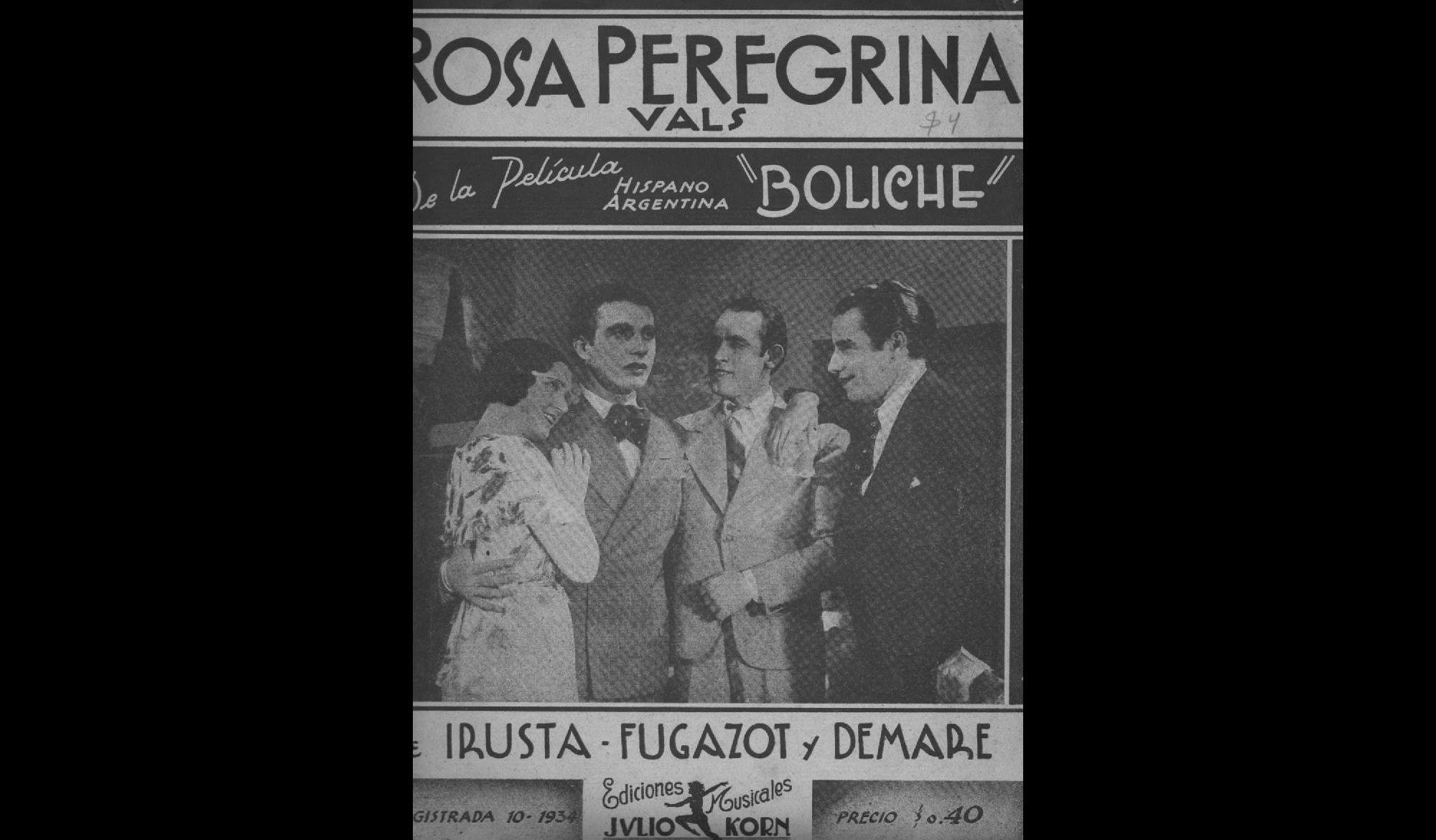

Lucas Demare found his way into the film industry through music, tagging along when his

brother was hired to perform in the now-lost Spanish musical film Boliche made in 1933, which

Lucio Demare received third billing in.

After his bit part in Boliche, Lucas Demare decided to leave behind music in pursuit of a career

in film. He’d work as a production assistant, slater, or third assistant director on Spanish film

productions, often without pay so that he could study the technical side of filmmaking. After a

few years he had worked his way up to second assistant director, and was set to make his

directorial debut in Spain. He purchased the rights to Àngel Guimerà’s play Martha of the

Lowlands intending to film it in 1936, but the outbreak of the civil war forced him to return

home to Argentina. 4

In 1937 Lucio managed to hook his younger brother up with a job as the floor manager at Río

de la Plata film studios, and the following year Lucas would make his debut as a film director

with the romantic comedy, Two Friends and a Lover. It starred his future wife, Norma Castillo.

There’s a white telephone in it, but I’m not sure if it qualifies as one of the “white telephone”

movies that professor Tim Barnard decried. Lucio would compose some of the music for that

film, and continue to work with his younger brother, composing the scores to many of Lucas’

films, including Hijo de Hombre. I think to its detriment, the La Sed release of the film replaces

Lucio’s music with a more conventional score by Spanish composer Manuel Parada.

Demare’s name may not mean all that much to people reading this, but he was one of the most

respected Argentine filmmakers of his day. Three of his films would compete in the Cannes

Film Festival - Los Isleros (1951), El Último Perro (1956), and Zafara (1959) - though none would

win big. Demare was ubiquitous enough with classic Argentine cinema, that I nearly overlooked

that his name is on the cover of my copy of Argentine Cinema (published in 1984, the first

English language book on the subject) hidden in plain sight on the poster for his film La Guerra

Gaucha (1942).

Demare intended to shoot Hijo de Hombre on location in the Chaco Boreal in Paraguay, using

the real places the story is set in, and utilize an old Cacho War military barracks to house the

cast and crew. However, after a gruelling 15-day location scouting process, it was decided that

it would have been more or less impossible to transport and take care of the hundred or so

people and all the equipment required to make the film. At least Demare left with a feel for the

place. He settled instead for shooting in the northern Santiago province of Argentina as a

substitute for the dry Paraguayan region. It’s certainly a more geographically accurate

substitute than southern France being transformed into South America for The Wages of Fear.

Apparently Santiago was similar enough to the Chaco Boreal, that when Hijo de Hombre was

released most people assumed it was shot in Paraguay anyway.

Pictured below, Southern France:

Demare’s approach to Roa Bastos’ material is straightforward but thoughtful. There’s an

understanding and faithfulness to what’s on the page. It seems as if Demare made it his

mission to carry Roa Bastos’ story like precious cargo to his audience, with as few dings and

dents as possible.

Roa Bastos had initially sold the film rights to his novel for very little (which he was never

actually paid) to an inexperienced producer, but after finding out that Demare had read the

novel and wanted to adapt it, they conspired to pressure that producer into handing back the

rights. Roa Bastos seemed to respect Demare, and would compare his style to the famous

Spanish poet Federico García Lorca, who was murdered by fascists during the beginning of the

Spanish Civil War (though for all my ignorance of Lorca, that could have been a backhanded

compliment). Demare’s treatment of the material would also be appreciated by Roa Bastos

devotees. Professor Helene Carol Weldt-Basson, a specialist on Augusto Roa Bastos referred

to Demare as a master filmmaker, and described the film as a “stunning cinematographic

accomplishment.”

Going back to what I described in Argentine films earlier, there’s a blend of classic Hollywood

and arthouse European influence on display in Hijo de Hombre. Demare has one foot firmly and

comfortably in each approach. At times Demare’s muscular artistry reminds me of Classic

Hollywood filmmakers like Howard Hawkes, George Stevens, or William Wyler. Demare himself

admitted to being greatly influenced by John Ford and Frank Capra. I think though, in the case

of Hijo de Hombre, John Huston is the Hollywood director whose name first comes to mind,

and whose Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948) is, I think an obvious influence on the film. The

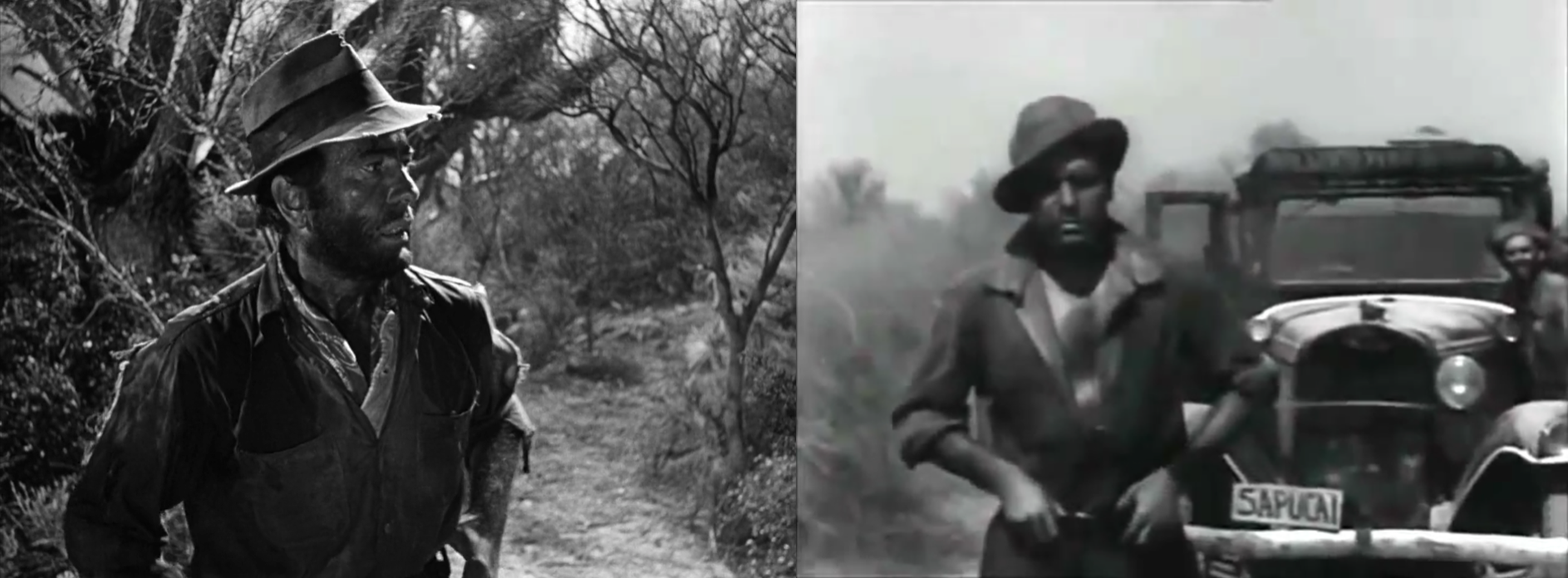

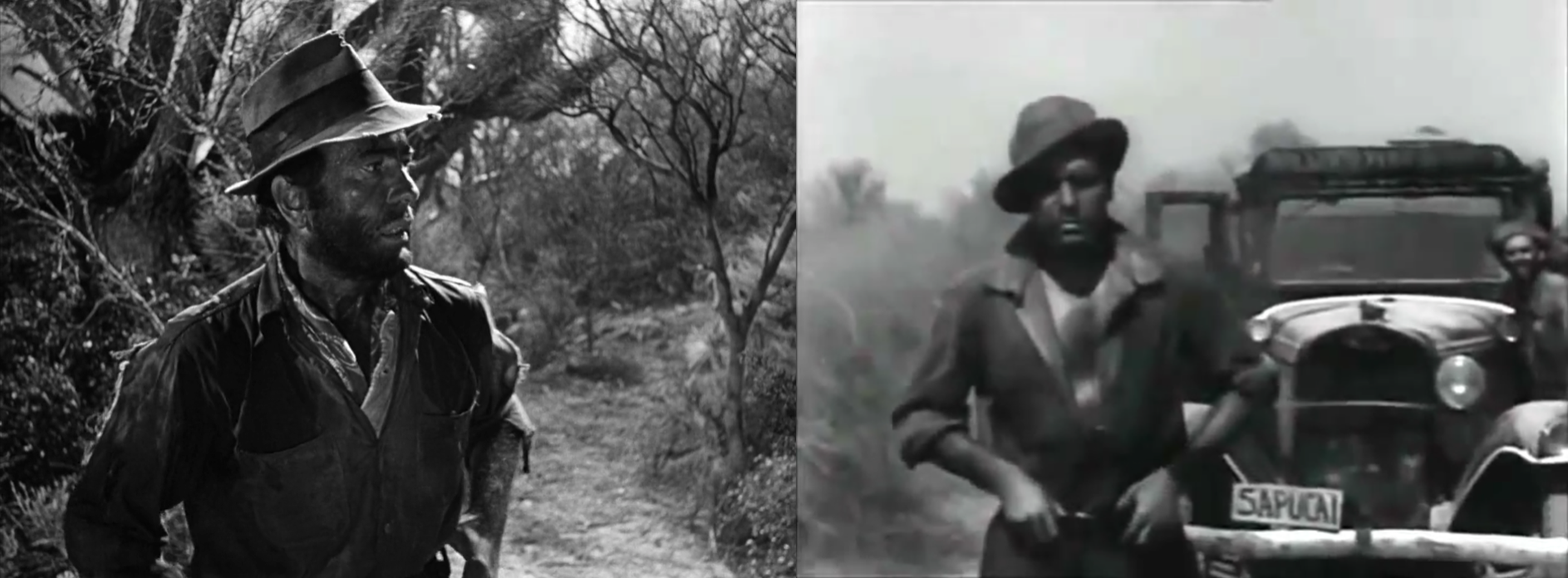

lead actor is even dressed in a way that resembles Humphrey Bogart.

AGUATEROS

Before I get too far ahead of myself, I should mention that the lead is the great Spanish actor

Francisco Rabal. It wasn’t unusual for A-list Argentine films to bring in international talent,

usually for the purpose of making the film more marketable abroad. Hijo de Hombre was

Rabal’s immediate follow-up to Luis Buñuel’s Viridiana (1961), and I wonder if he may have

been inspired to become involved in an Argentine film by his Viridiana co-star Fernando Rey

who had experience with Argentine film productions (and had just married the beautiful

Argentine actress Mabel Karr in 1960).5 Buñuel's filmmaking was likely an influence on Hijo de

Hombre too, though it doesn’t resemble Viridiana nearly as much as it does Francisco Rabal’s

prior collaboration with Buñuel, Nazarín (1959), with its desert landscapes and subtle but

impactful visuals. I don’t know if Buñuel and Demare would have met, but both Nazarín and

Demare’s own film Zafara were in competition during the 1959 Cannes Film Festival, though

they’d both lose out to French filmmaker Marcel Camus’ beloved Brazilian endeavour, Black

Orpheus.

Hijo de Hombre also recalls Nazarín, in that Rabal again plays a would-be saviour, a man with

with an air of unpretentious piety, who is put through the ringer in the desert and ultimately

fails. The name of Rabal’s truck driver hero is Cristóbal Jara, sometimes just called Cristó in

the film, which I take as an allusion to Jesus Christ. In the novel it says that he, “seemed to be

part of the truck, a living and thinking part that radiated strength and will to the tendons and

nerves of the broken down vehicle. His skill was already well known around the army base and

the outpost. The truck was full of patches and repaired parts, but no one laughed at the motto

painted on the roof. In truth or in jest, he had a reputation for making the truck run on a bit of

wire and even without gasoline.” He’s a mechanical miracle-worker.

That motto, mentioned in the excerpt appears in the film as “Soy Lento Pero Seguro”, meaning

“I’m Slow But Steady”. In the novel the phrase is written in Guinari rather than Spanish, but has

more or less the same idiomatic meaning, and could be translated as “Nothing Hurries Me, and

Nothing Halts Me.”

It was common for mottos like that, or names or phrases to be painted onto trucks in South

America. A detail that was used to great effect in William Friedkin’s Sorcerer (1977), with its two

hero trucks named ‘Sorcerer’ and ‘Lazaro’. Sorcerer happens to also star Francisco Rabal as

one of its four leads, and watching it now, Rabal’s presence takes on a meta-textual element,

like his character Cristóbal Jara has been resurrected to drive a truck through perilous terrain

once more and meet a similar fate. Only now he’s transporting nitroglycerin instead of water.

Sorcerer is ostensibly a remake (or based on the same source novel if you want to be

particular) of another film I’ve mentioned, The Wages of Fear, and I think Friedkin managed to

make his version worthwhile by distinguishing it from Clouzot’s in philosophical outlook. I’ve

always seen The Wages of Fear as a nihilistic film with its characters at the mercy of the cruel

capriciousness of an uncaring universe, whereas Sorcerer I consider a determinist film, with its

four truck drivers’ fate locked-in during their prologue vignettes, and their fate is inescapable.

Watching the film now, I believe that The Wages of Fear was only one of Sorcerer’s parents,

with the other of course being Hijo de Hombre. I haven’t seen Friedkin cite it as an influence,

but there are a number of strong parallels between the two films, and at the very least Rabal’s

presence ensures that there was someone on set who would have been thinking of Hijo de Hombre.

The Wages of Fear is the film that seems to make the most sense to compare Hijo de Hombre

to, and there are moments when that comparison seems encouraged.6 Demare cranks up the

tension and suspense in a Clouzot-like way, without direct imitation, and there are certain

images that come across as inspired by The Wages of Fear without being outright lifts.

However, comparing the two films feels a bit like comparing Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai to

Eiichi Kudo’s Eleven Samurai. The Wages of Fear is an all-time great, but Hijo de Hombre is

leaner, faster, and more focused.7 The Wages of Fear takes its time, and at nearly two and a

half hours long, it only gets rolling roughly an hour into its runtime, after setting up character

motivation and tone. Hijo de Hombre hits the ground running. The opening scene is of the

battalion of soldiers in a state of extreme thirst, which establishes an urgency that will

dominate the entire film. Every second of its ninety-one minute runtime matters for its

desperate characters, and backstory is filled in with reverie-like flashbacks while on the go.

Hijo de Hombre also distinguishes itself from The Wages of Fear with its leading lady. The

Wages of Fear leaves Véra Clouzot (Brazilian-French actress and wife of Henri-Georges

Clouzot) in the dust both figuratively and literally. Can I get away with only saying that Henri-Georges

Clouzot’s depiction of the women in his films was ‘complicated’ and leaving it at that

for this article?

Hijo de Hombre’s lead actress is Olga Zubarry, who plays a nurse named María

Saluí. She’s as tough as she is compassionate, and for most of the film feels as much like the

protagonist as Cristóbal does. The character’s background as a prostitute is explored in a

flashback, and like Cristóbal evoking Christ, her name evokes Mary Magdalene (this is further

compounded with her name being changed to Magdalena in some of the European versions of

the film). Again Nazarín is echoed, with María resembling the character of Beatriz in that film.

Beatriz who follows and falls in love without consciously realizing it, with the character of

Father Nazarín. María becomes unsettled when her sexual advance on Cristóbal is treated not

with contempt as others do, but rather indifference. She becomes compelled by him. The novel

gives clear insight into her fixation; “It tormented her not to know what he felt, not to be able to

cross the distance between them.” He tries to leave her behind, but she halts the convoy, and

makes Cristóbal take her with him on the mission, saying that they’ll “need a nurse” to finally

convince him.

According to Helene Carol Weldt-Basson, in her essay All Women Are Whores: Prostitution,

Female Archetypes, and Feminism in the Works of Augusto Roa Bastos, nearly all of Roa

Bastos’ heroines are prostitutes. She elaborates that “…Roa Bastos’s portrayal of women as

prostitutes fail to result in a stereotyped portrait of women. Indeed, the object of this analysis is

to illustrate how Roa Bastos paradoxically employs the figure of the prostitute, as well as other

fixed female archetypes, to achieve a complex, postmodern view of women, as well as to

communicate a feminist message to the reader…” It’s easy to see on screen how María Saluí

defies cliché. She’s as hardboiled as the best of them, and often a more active character than

Cristóbal. For example while being bombed she bravely collects medical supplies from an

ambulance truck before it’s destroyed in a fiery explosion, while others stand back and gawk.

She’s a road warrior.

Olga Zubarry was perfectly cast as María Saluí. She was known for her bold and adventurous

personality, and had achieved notoriety for supposedly being 'the first actress to appear nude

in an Argentine film’, with The Naked Angel (1946) which is based on an Arthur Schnitzler

novella. I was worried it might turn out to be a sort of proto-David Hamilton film when I found

out that it was shot when Zubarry was only 16 years-old, however as she clarified, “There was

no nudity. At that time I could not be nude, especially because I was younger. What judgments

the producers and the owners of the studio had to endure! I had to wear a flesh-coloured

mesh.” In watching the film, it’s clear that the filmmakers clearly played it safe, no matter what

audiences imagined they saw.

The Naked Angel wasn’t Zubarry’s first role, but it was the one that catapulted her to stardom,

and a career that would span six decades (Hijo de Hombre was her thirty-fifth film). She had

also starred in La sangre y la semilla (1959) where she played a 19th century Paraguayan war

widow. The film was co-written by Augusto Roa Bastos, so there was some connection prior

to her being cast in Hijo de Hombre.

Zubarry would often be characterized as “Argentina’s own Ingrid Bergman” for her talent and

beauty. In a 2011 interview (just a year before her death), reflecting back on her long career, she

cited her role in Hijo de Hombre as the one she was most proud of. I wonder if it’s in part

because it showed a strength to her that wasn’t often depicted with the elegant roles she

typically had. During a flashback to María’s life before the war, under Film Noir lighting,

surrounded by smoke from her cigarette, Zubarry is shot with all the grace in the world, but it’s

a fleeting moment, there only to juxtapose with the rest of the film, where the War of Thirst has

covered her with dirt, motor oil, and blood.

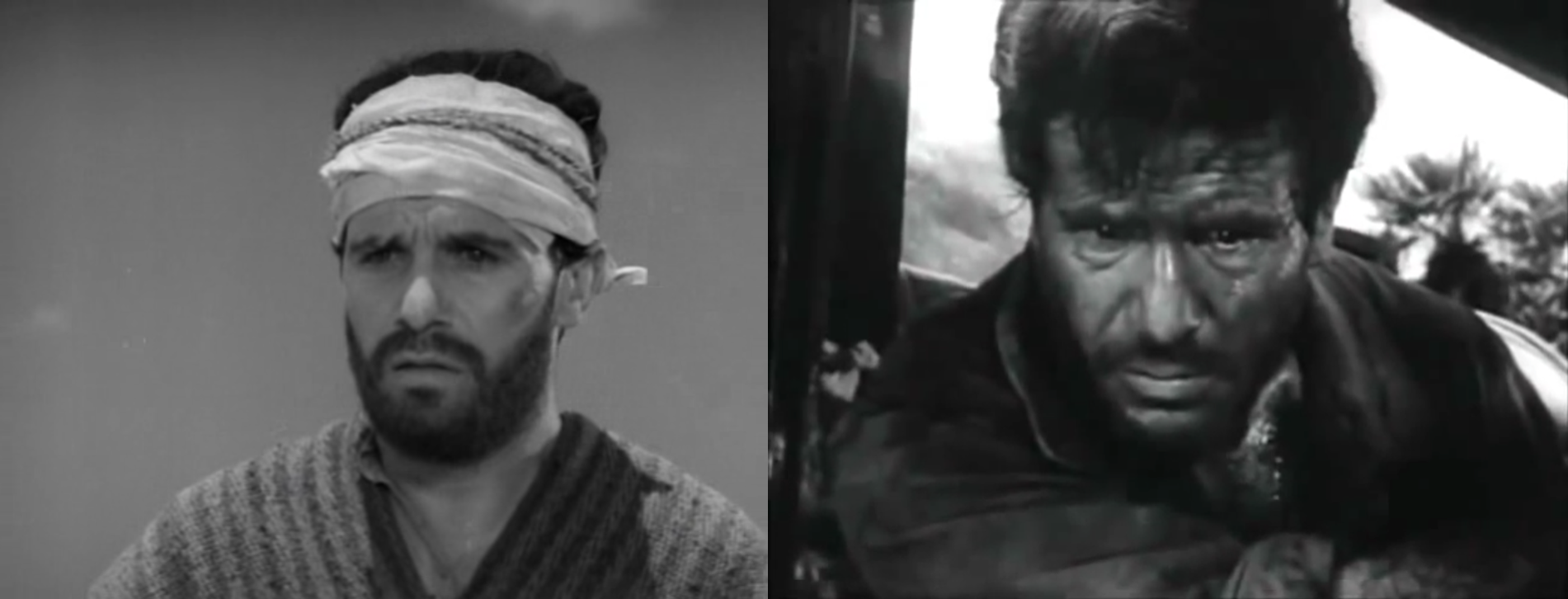

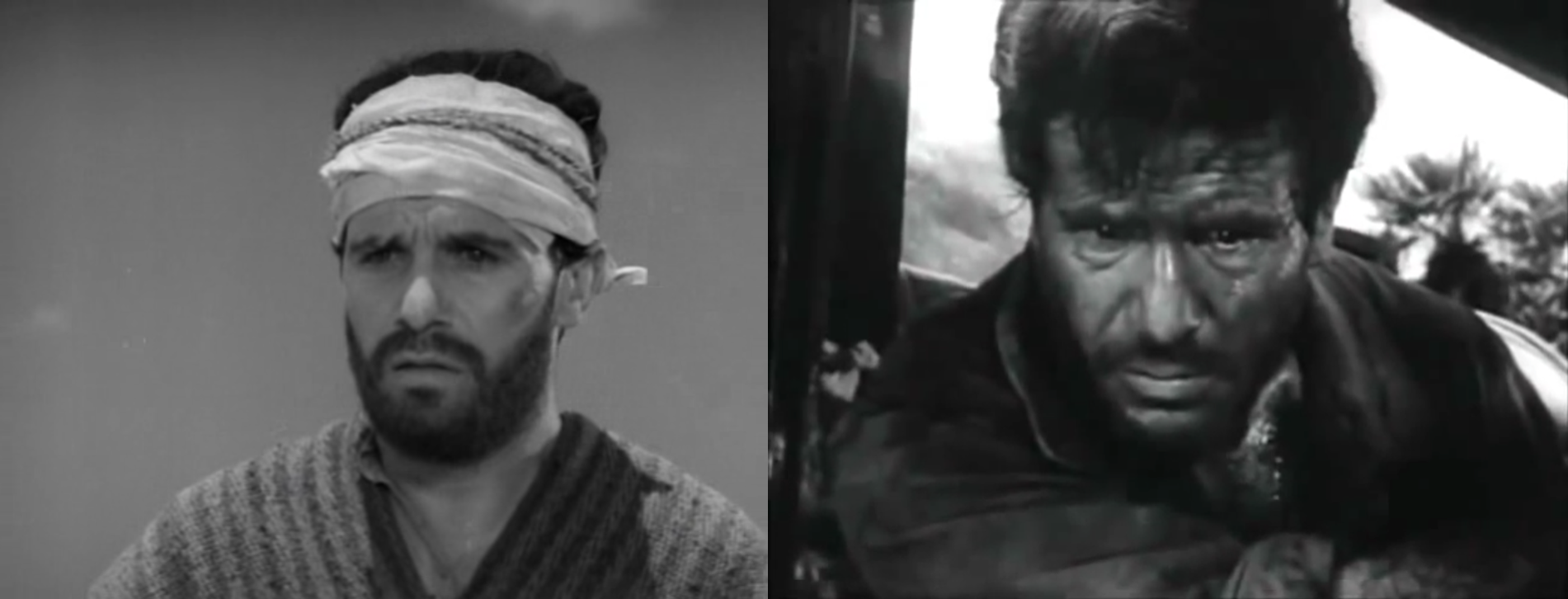

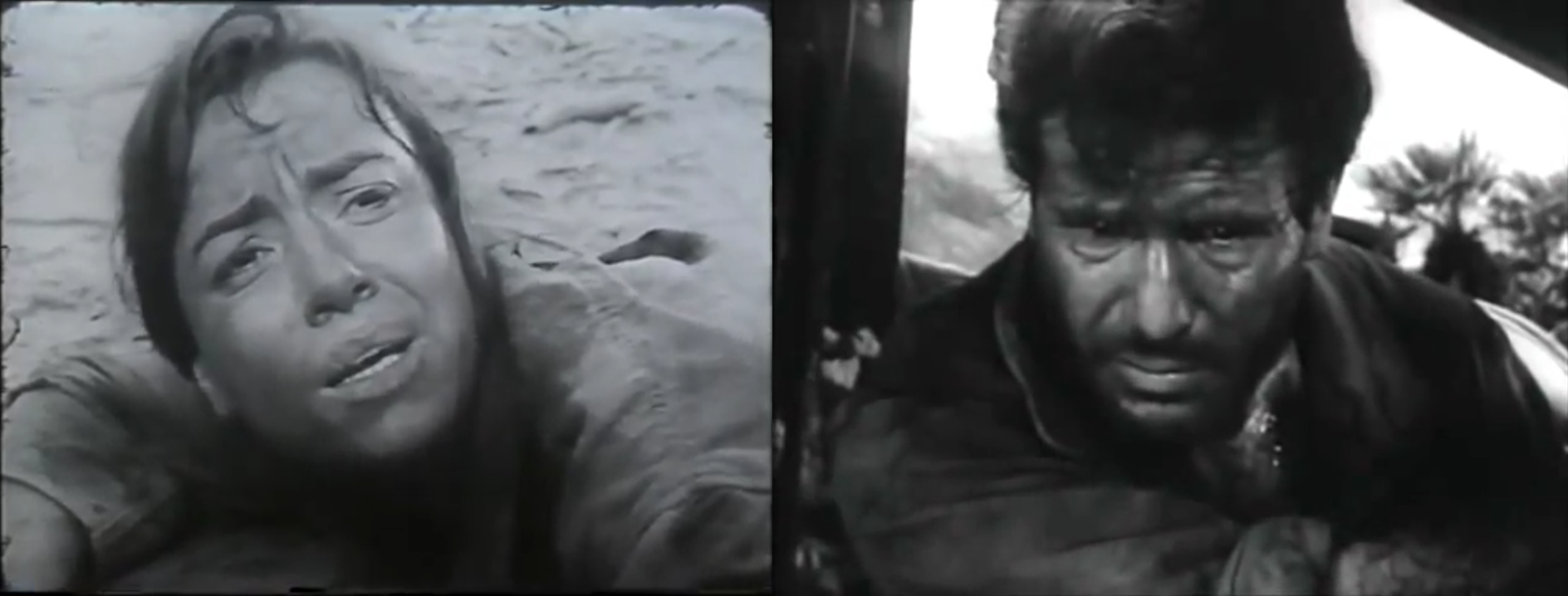

To support the film’s two leads and round out the cast, Lucas Demare brought in Paraguayan

actor Jacinto Herrera, who he had worked with previously on his acclaimed colour western El

Último Perro (1956). Here he plays the leader of the convoy, Sergeant Silvestre Aquino.

Herrera’s calm, burly presence balances the quiet intensity of Francisco Rabal’s performance.

He brings a sense of stability to the film.

Herrera’s most memorable scene comes just after an attack by Bolivian biplane bombers on

the helpless trucks. A bomb punctures one of the vehicles but does not detonate. Sergeant

Silvestre takes it upon himself to try to defuse the bomb, or rather as he says “defang” it,

knowing that it could explode at any moment. With the explosive centimetres away from his

face, it’s classic high-tension stuff. Very suspenseful…

Just when it seems he’s got it, the bomb goes off. Silvestre and the precious truck are blown

completely away. A gruesome detail from the novel was excised, that Sergeant Silvestre was

decapitated in the blast. His death cements the seriousness of the situation. It sinks in that

we’re not watching an adventure film like Cent mille dollars au soleil (1964), which stars Jean-

Paul Belmondo and Lino Ventura as competing truck drivers in North Africa. Cent mille dollars

au soleil has its cynical edge and is an excellent film, but it’s also a ‘fun’ film. Hijo de

Hombre’s heart is in a more somber place. Anything bad can and probably will happen to its

characters.

Threats to the convoy come not only from the enemy Bolivians, but also from Paraguayan

comrades who want to drink more than their fill. One stunning sequence has what’s left of the

convoy arrive at an allied outpost. Thirsty soldiers nearly riot when they're told that the water

isn’t for them, but for a special mission. Demare makes sure to pan across their desperate

faces. The drivers finally relent and give up a half cup of water to the lined up soldiers. While

the drivers are giving out water to the wounded, one soldier who had already gotten a cup

shoots himself in the hand and pretends that he hasn’t gotten any. When a driver who

recognizes him examines the hole in the hand (which introduces an image of Stigmata into the

film) he recognizes the self-inflicted wound for what it is. “You would have been better to shoot

to kill,” the driver tells the soldier and kicks him to the dirt.

Other obstacles are even more frustrating. At one point the whole convoy is forced to go

backward on a narrow path for a very long stretch after running face to face with an oncoming

truck full of wounded soldiers, undoing large chunk of their progress towards their destination.

As imposing as the impediments are, Cristóbal has an unwavering determination that carries

him through. When the tires of the truck are slashed, rather than give up or panic, he simply fills

them with esparto grass to keep rolling. At one point María asks Cristóbal if he believes in

miracles…in “things that only god can accomplish”. His answer is that he believes there’s

nothing man can’t accomplish.

But in this accursed Eden, no miracle is possible.

Seeing Cristóbal and María overcome the seemingly insurmountable in their truck, I’m

reminded of George Miller’s heroes, Mad Max and Furiosa in Mad Max: Fury Road (2015).

The Mad Max films became increasingly fantastique with every instalment, and are far removed

from the realism and history of Hijo de Hombre, but it’s also hard not to see Hijo de Hombre as

a sort of prototype for the action and visual storytelling that characterizes those films. On one

hand it’s entirely possible that there’s only so many ways to stage interesting and exciting

action around a truck in the desert - driving it through dust storms, hanging off the top of it,

setting it on fire, and defending it like it’s a fortress - but still, enough images and moments

strike me as similar enough to at least speculate that Hijo de Hombre may have planted a seed

of influence in George Miller at some point in time.

FiNAL DESTiNATiON

The final obstacle for Cristóbal and María comes in the form of an ambush by thirsty Bolivian

soldiers. Cristóbal is shot up, and the soldiers capture the final water truck. They even shoot

holes in the sides of the tank to get at the liquid right away. In the novel Roa Bastos compares

the sight of the soldiers drinking from the truck, to a sexual violation. It seems Demare tried to

visually realize that simile with the repugnant enthusiasm of the soldiers, and the way some

grin after drinking the water they took by force. In that way the scene takes on a subtext for

other casualties of war.

It’s María who springs into action, grabbing a bag of grenades, and then fiercely tossing them

at the soldiers. The novel describes her as looking “wild and terrible with her halo of dust”. She

singlehandedly manages to drive the enemy away.

Wounded, Cristóbal staggers up to the still running tap, spilling out precious water. His hands

are too mutilated to turn it off, so he uses his elbow. María helps to quickly plug up the bullet

holes in the water tank with sticks.

Apparently the filming of Cristóbal being wounded also resulted in an injury to the director. In

an interview with the journalist Julio Ardiles Gray, Demare described how he took it upon

himself to be the one to fire the rife with blanks (made weightier by talcum used to create more

smoke on screen) at Rabal. The rifle kept getting clogged with dust, so it wouldn’t shoot,

and while pointing the rifle downwards to avoid getting any more dust in it, the gun went off

pointed directly at Demare’s foot. In what must have seemed like a scene right out of the

movie, Demare had to be rushed to a doctor forty kilometres away in one of the 1928-model

trucks used in the film. The doctor thought it would be necessary to amputate two toes, and

Demare describing the sight said that he wished he could have amputated his toes himself.

Not wanting to delay production, he convinced the doctor to only clean the wound and sew up

everything up as well as possible. Luckily he kept his toes, but Demare would have to continue

to shoot while on “rustic” crutches created by the film’s carpenters.

In the novel it mentions that the sight of his swollen and mangled hand reminds Cristóbal of

Sergeant Silvestre’s head that was popped off in the explosion. Driving the truck seems

impossible now but Cristóbal, being the man who believes there is nothing man cannot do,

concentrates and comes up with a solution.

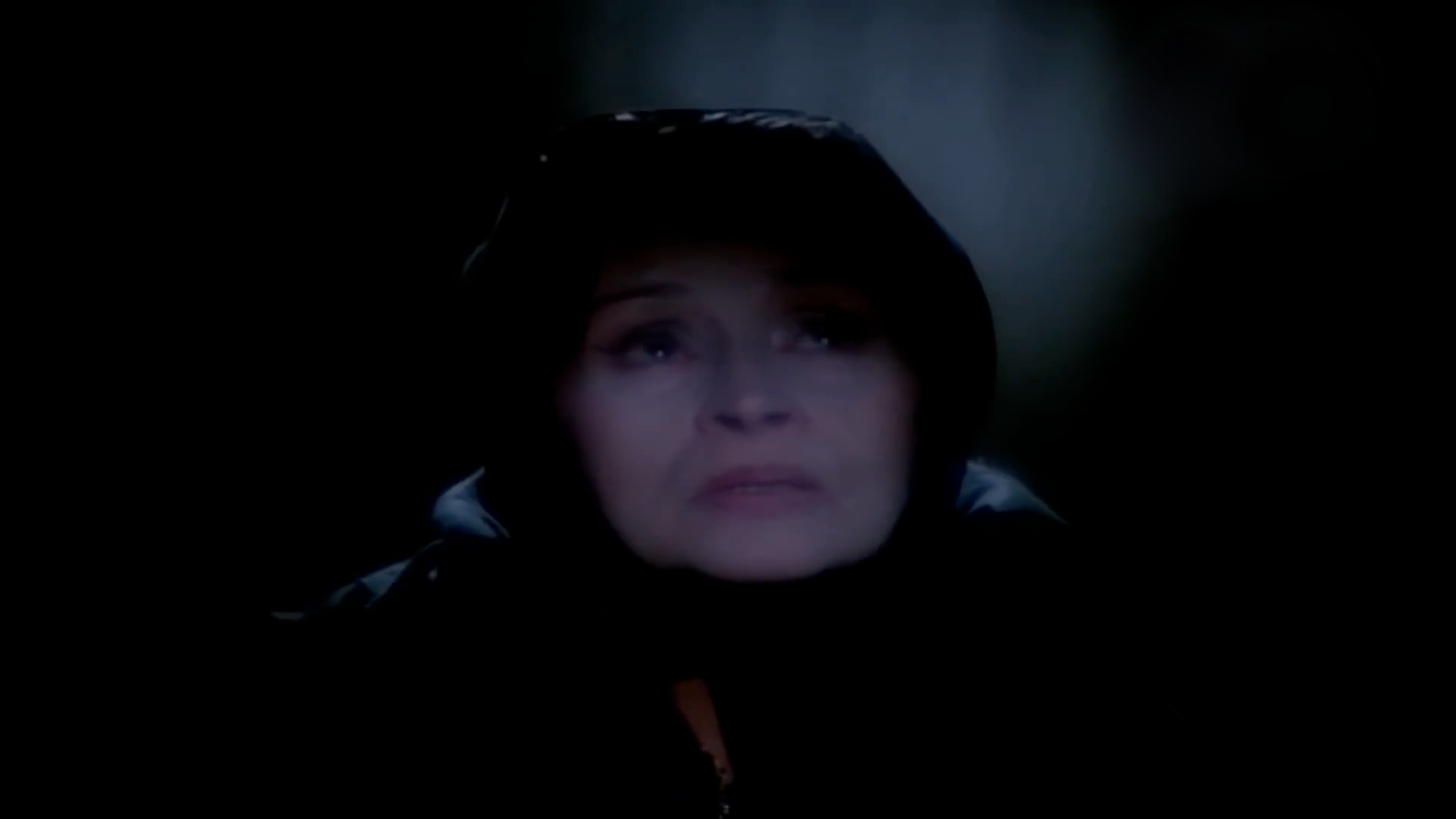

Cristóbal has María use chickenwire to tie his hands tightly to the stick shift and steering

wheel. “Pronto,” he tells her when she hesitates at the grotesque sight. It’s like a strange

automotive variation of crucifixion. Not that everything that preceded in the film wasn’t

impeccable, but this is the scene where during my first time watching the film, I realized I was

seeing something special.

María is clearly in her own anguish with a tired and pained expression, but Cristóbal is too

focused to notice. During the scene, I’m astonished by how much Olga Zubarry reminds me of

Renée Jeanne Falconetti in The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928).

Just as she finishes, María collapses, and Cristóbal can see the shrapnel wound on her back.

Wired in, it’s impossible for him to get out to go to her. They share a final look, and it’s a credit

to the actors, how one look without any words between them can contain so much; the

distance between them filled with a deep and growing ocean of regret, realizing just a little too

late that they could have lived and had a life together. That everything they’ve been through

was a mistake that there is now no escape from. The wheels of fate (along with the wheels of

the truck) are already in motion. There is no going back. The only thing left is the mission, and

Cristóbal will have to make the final stretch alone.

From the novel:

For now the only thing that mattered was to go on…through the desert, through the merciless

heat of the sun, and the head of his dead friend, through this awful country where life and death

could not be separated. That was his destiny. And what other destiny could there be for

Cristóbal Jara?

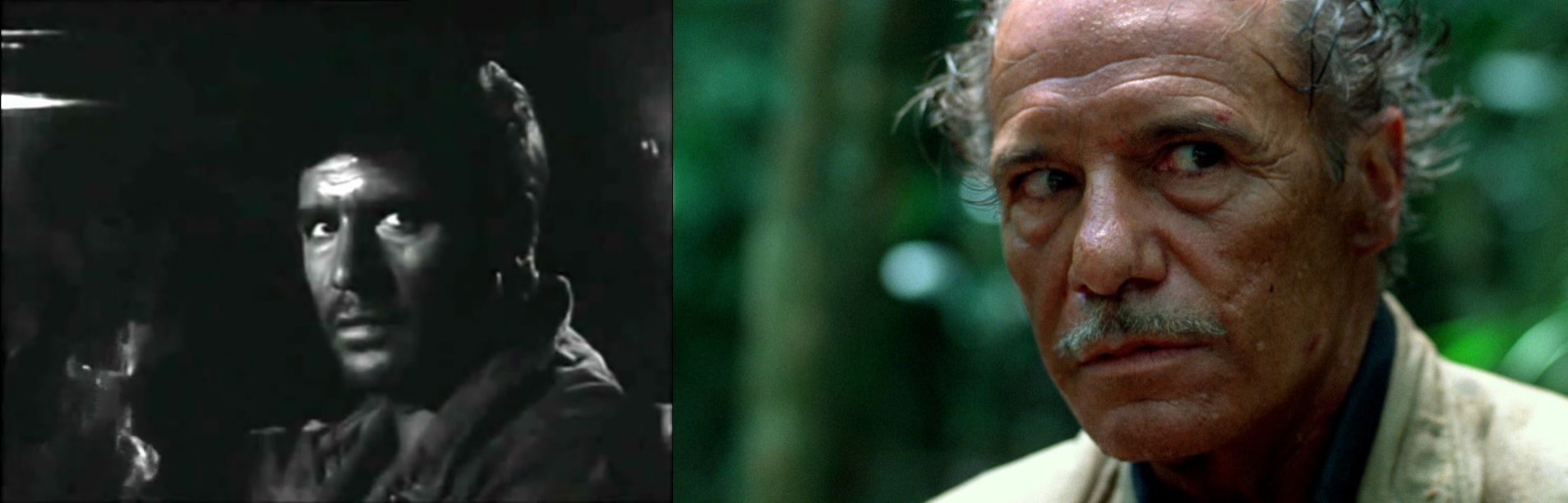

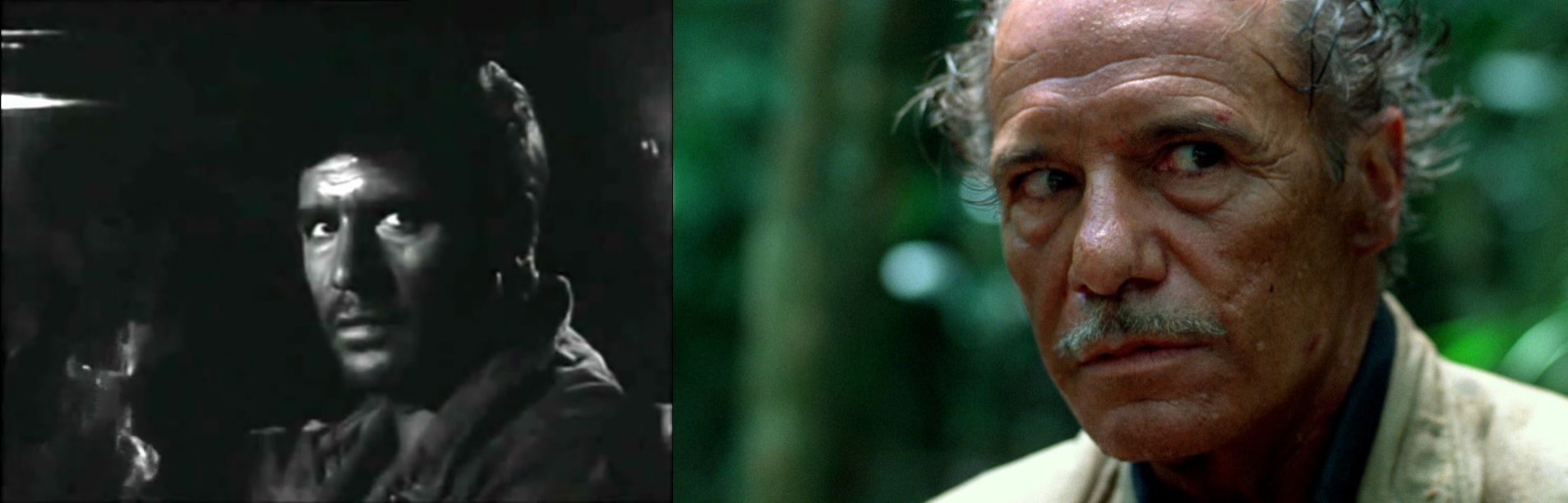

I think the desert is a perfect stage for existential stories. It’s where devils can be confronted

both outside and within. Unfortunately it’s become something of a cliche, but I love a good

‘wandering in the desert’ film. Driving in the desert is even better. At this point in particular I’m

reminded of Jauja and Zama wherein their protagonists (played by Viggo Mortensen and Daniel

Giménez Cacho respectively) are worn down to nubs of men by the landscape, just like

Cristóbal.

Both the man and the vehicle are pushed to their limit. He drives the truck, but judging by his

expression it may as well be a cross he carries. Cristóbal bleeds and the truck burns. Nothing

Hurries Me, and Nothing Halts Me.

In the novel, Bastos described the truck as being like a mythological animal. Some archaic

behemoth, rolling across the landscape, flames and smoke spewing from it. That sort of

animism in trucks has appeared in other films, one of the best instances of which would be in

Steven Spielberg’s Duel (1971). Also, once again I’m reminded of Mad Max, specifically at the

climax of The Road Warrior (1981). Just like Cristóbal, Mad Max fatalistically drives his truck,

his bruised face half-hidden in shadow and one hand on the steering wheel. I’m willing to

double down on my speculation and would be ready to eat my hat if George Miller hasn’t seen

Hijo de Hombre.

Cristóbal struggles to keep conscious. You want so badly for him to make it in time to save the

battalion. To make all the suffering that we’ve seen transpire throughout the film worthwhile. A

redeeming act. For a moment it seems possible that the man can perform a miracle. Of course,

what sort of a film would it be if it gave us exactly what we wanted?

But in this accursed Eden, no miracle is possible.

There’s one more key actor in the film who I haven’t yet introduced, Carlos Estrada. Strangely

the only other film I’ve seen Estrada in is the 1987 action movie, Rage of Honor which is a

Cannon Films production about a ninja traveling to Argentina to battle a drug lord. It stars Sho

Kosugi, who is more or less responsible for kicking off the 1980s boom of Ninja in popular

culture. Estrada has limited screen time in Hijo de Hombre, but plays the significant role of

Miguel Vera, the military officer in charge of the dying battalion. The novel characterizes him as

an upperclass man who “despite having been born out in the country, did not possess the solid

good sense of the peasantry... He did not know how to find his way, even within permitted

limits. He was only able to lose himself.” In other words, he’s completely unlike Cristóbal.

Miguel Vera has given up and is ready to take his own life, but decides first to take care of his

remaining men, who twist and moan in extreme agony. Like some Bruegel scene of Hell. Vera

uses a Maxim machine gun to put his thirsting troops out of their misery. He then lifts his pistol,

which has a cross dangling from it to his head, but just as he’s about the pull the trigger the

quiet of the dead allows Vera to hear a sound he couldn’t before, the sound of the truck. It’s

more or less the same horrible-horrible mistake that Thomas Jane’s character makes at the

end of The Mist (2007), though played much less melodramatically.

Just as Cristóbal reaches his destination, he succumbs to his wounds. His mission complete,

he runs the truck into a tree to finally halt it. Our hero dies with his head on the steering wheel,

gazing at us. The persistent beep of the truck’s horn is decidedly undignified.

All Vera can do is bury Cristóbal. Dust to dust. He marks the grave with a cross, and I think of

how simultaneously strong that symbol is, while also not being nearly strong enough for this

land. There are things that man cannot accomplish. Roa Bastos’ sense for the cruel absurdity

of war is strongly felt. Pointless bravery, pointless desire, pointless sacrifice, pointless

martyrdom, all for this dry Chaco Eden.

It’s an incredibly bleak ending, but could be interpreted as not entirely hopeless. One person

was saved after all. It might be worth contrasting the ending with the epilogue of another war

film, Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan (1998). An elderly version of the titular Ryan visits

the grave of the man who saved his life, and Spielberg emotionally stacks the deck by having

Ryan surrounded by his loving wife, children and grandchildren to reassure its audience that

the sacrifice of its characters was not wasted, and that Ryan lived the best life he could. Hijo

de Hombre gives no closure on what Miguel Vera will do with the lease on life he’s been given,

and you’re left with a feeling of ambivalence. In the novel at least, Miguel Vera dies not long

after the war. Whether it was by accident or by guilt-driven suicide, is unclear to me, but it may

have been meant to be left ambiguous.

FATE

So where has fate lead to?

It might not be surprising that as upsetting as it is, Hijo de Hombre was not as big a

commercial or critical hit as some of Demare’s previous films. It would be three years before

he’d make another film, an uncharacteristically long period of downtime for someone who had

been making a film or two (or sometimes even three) a year since the beginning of his career.

At least Olga Zubarry’s performance wouldn’t go unnoticed, and it won her awards at the Berlin

Film Festival and the San Sebastián Film Festival, the later of which also gave its top prize to

the film.

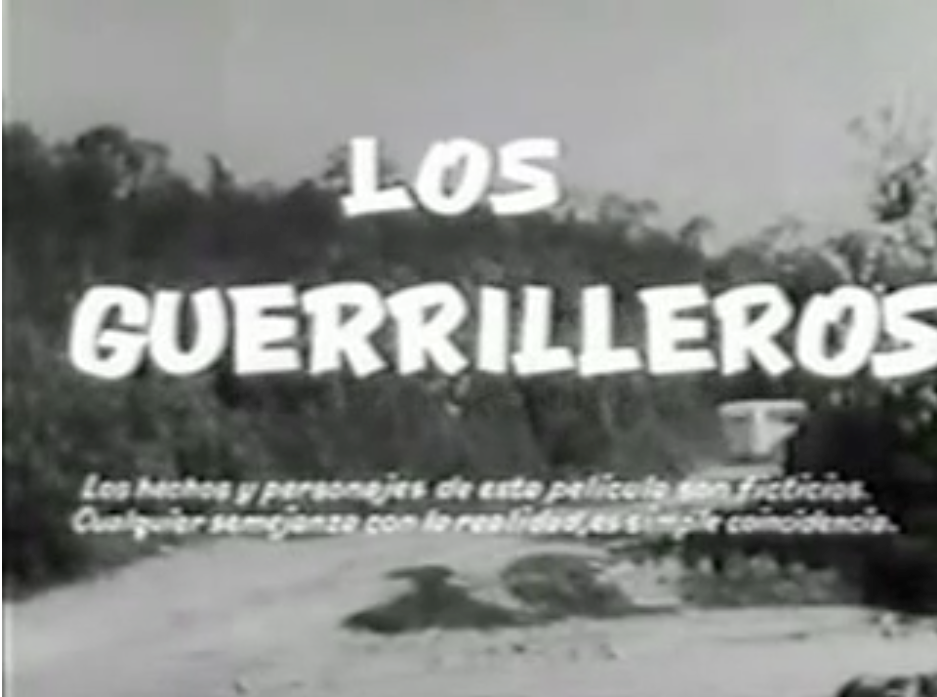

In the years since its release, Hijo de Hombre has become one the most beloved and best

remembered of Demare’s films, though that may not be saying much especially considering the

sorry state the film is in. The best version of the film available is a thirty year old telecine

uploaded to youtube by Lucas Demare’s daughter, musician and actress María José Demare.

She has a long film career of her own, beginning with a role in her father’s 1965 thriller, Los

Guerrilleros, which was also Lucas Demare’s second collaboration with Olga Zubarry.

Francisco Rabal wouldn’t have the chance to work with Demare again, but he did star in

another Argentine film released the same year, La Mano en La Trampa which was directed by

Leopoldo Torre Nilsson. There’s no desert in La Mano en La Trampa, but there is dessert.

Rabal holding an ice-cream cone during a scene in La Mano en La Trampa:

Augusto Roa Bastos would continue to write screenplays, including a segment in the horror

anthology film, Demon in the Blood (1964), and would work again twice with Demare. He’d

write the screenplay for La Boda (1964), which is not based on one of his own stories, but

instead a novel by Spanish author Ángel María de Lera. It’s about a wedding night that seems

doomed by bloodshed. It’s the sort of film that isn’t easy to classify, but it’s very eerie and

disturbing.

Demare’s career continued to slow down in the 1960s. Films became infrequent and often

made with budgets lower than what they warranted. Demare even made an embarrassing anti-marijuana

film a la Reefer Madness (1936), though I wouldn’t fault him at all for taking what

work was available. A part of that was the decline in the Argentine film industry as a whole, but

it seems that critical interest in Demare’s work also waned. With his strong sense of craft and

cinematic convention, it’s easy to imagine Demare being considered antiquated by the 1960s.

There’s a classiness to Demare’s films that just seems out of step or old fashioned when you

remember that the later ones were being released at the same time as the films of someone

like the brilliant enfant terrible of Brazilian cinema, Glauber Rocha. Believe it or not, Demare

would outlive Rocha who died suddenly and tragically at age 42 in 1981... if only by two weeks.

It’s a bit like being reminded that Louis Armstrong outlived Jimi Hendrix.

The final film Roa Bastos would write for Demare would be La Madre María (1974), which is a

period drama based on the life of a Spanish woman who dedicated herself to helping

Argentina’s sick and poor. The film is bittersweet both for its story, as well as the fact that it

comes more or less at the end of both Roa Bastos’ and Demare’s film careers. As with many other Argentine filmmakers, the infamous 1976 coup d’état, where right-wing generals seized power, was a harsh turning point.

Roa Bastos would become one of the most celebrated Latin American authors, with his

screenwriting career (coming to a grand total of twelve films, with two other films not written by

him but based on his stories) viewed more as a curious blip in a formidable literary legacy.

While he’d never win a Nobel Prize in literature, he was often name-dropped as a likely

candidate, and he did win the prestigious Premio Cervantes prize for what is generally

considered to be his masterpiece, the 1974 novel I, the Supreme (the only novel of his that’s

available in English, and is newly back in print!). It’s about the historical figure, Dr. José Gaspar

Rodríguez de Francia, who was an archetypical South American despot, and held the title of

"Supreme and Perpetual Dictator of Paraguay” (and who was also a major inspiration for

Joseph Conrad’s seminal novel, Nostromo). Roa Bastos considered it and Hijo de Hombre, to

be part of a trilogy which he completed with his 1993 novel El Fiscal, which is about an attempt

to assassinate the Paraguayan dictator Alfredo Stroessner. After the 1976 coup, he’d leave

Argentina for Europe. He’d be given honorary Spanish citizenship, though he’d spend most

of his later years in France, working as a professor and writing.

In one of his last interviews, Demare would bemoan the state of the Argentine film industry, and

discuss the need for something better:

I have many projects that I would like to make, but I am waiting for the state of cinema in my

country to change. I think we need to make an important cinema, a cinema like the one we've

had, which, with some exceptions, has been neglected. As the country goes forward, our

cinema must also move forward. I hope they will give us a little more freedom in terms of

subject, so that we are not so restricted in important things. The country can not sustain itself

with a cinema like the one we are making. I understand that sexy or irrelevant movies are

necessary in any film industry. But I also believe that the industry should not be only that. I think

theme is now very limited…I believe that the country is capable. It is a mature country. It has

good writers, good actors, good directors, good technicians. The technical conditions have

improved a lot in the country, they are not of the came same quality as when I started making

films, but the materials have been quite modernized. The quality of our technicians is

demonstrated clearly; many technicians are working with great success abroad, like Ricardo

Aronovich, who is a valuable director of photography; or Lalo Schifrin an excellent composer; or

actors like Hector Alterio, who lives here, but is still linked to Europe.

I insist that we have a wealth of important people in all aspects. That is why we are obliged to

make an important cinema, a cinema that brings people back to Argentine theatres. Today

people prefer to see foreign films because they address issues that the public wants to see.

Many people even cross the river to Montevideo to see movies that aren’t shown here. And I do

not know why you can not see them. Because aside from the prohibition for minors under

eighteen, enough is enough. Let us see, because we are adults. I clarify that I'm not interested

in pornography. I'm talking about deep issues. The cinema is an important part of our culture.

It’s too bad Demare didn’t live to see the New Argentine Cinema, and the ascent of Argentine

filmmakers like Lucrecia Martel and Lisandro Alonso. I think they fulfilled that need for an

important cinema by creating mature and challenging films.

In that excerpt Demare also touched on an issue that I think is still at the centre of the fate of

classic Argentine cinema. So many of the films I watched while writing this seem terribly

neglected. They’re crying out for rediscovery, reappraisal, and restoration. Hijo de Hombre

especially, as it’s better than the run of the mill ‘forgotten masterpiece’.

Now we reach the end of the road, and like life; the path may have been winding, but the

destination is certain.

~ AUGUST 8, 2019 ~

1 Roa Bastos had written an earlier novel, El Fiscal, which he destroyed before publication. He

then later wrote a different version of the novel from memory, which would eventually be

published in 1993.

2 I was completely oblivious about the Chaco War before seeing the film, and while the

premise of fighting to the death for the oil rights to a territory with no oil, I’m not sure it’s quite

as absurd as The Football War between El Salvador and Honduras, which was triggered by, as

the name suggests, a game of football.

3 I just wanted to sneak in that Armando Bó is the grandfather of screenwriting cousins Armando Bó & Nicolás Giacobone, who won an academy award for Birdman (2014).

4 Martha of the Lowlands would eventually be adapted to film in Germany. The end result

would be Tiefland (1954) directed by the notorious Leni Riefenstahl.

5 Rabal’s other Viridiana co-star Silvia Pinal, starred in a play called La Sed, which I had

wondered might have had something to do with the film, but it turns out to be only a

coincidence, and it was simply a Spanish language production of Henri Bernstein’s La Soif.

6 I don’t know if Clouzot and Demare would have met, but they were in competition in the 1956 Cannes Film Festival, with Clouzot’s The Mystery of Picasso and Demare’s El Último

Perro.

7 Likely not an influence on Hijo de Hombre, but for anyone wants something similar from around the same time, I’d highly recommend the episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents, titled "Escape to Sonoita" which first aired in 1960. I think a strong case could be made for it being the

best episode of the entire series. It involves an oil truck stolen by thieves who become so

thirsty they end up killing one another over a tiny bit of water, and of course it has a great ironic

twist at the end when it’s revealed that the truck was in fact carrying water rather than oil. It

features a young Burt Reynolds, Murray Hamilton (the mayor in Jaws), James Bell, and Harry

Dean Stanton. The episode was directed by Stuart Rosenberg who would go on to make Cool

Hand Luke.