FRUSTRATING FILMOGRAPHIES #2

page 2

john cribbs

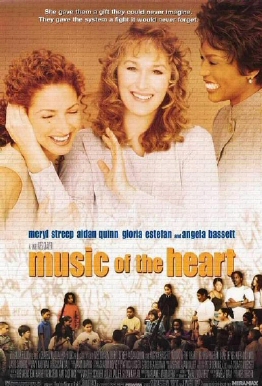

wes craven's MUSIC OF THE HEART

The movie's chief antagonist is an envious colleague who doesn't cotton to Meryl's violin-teachin' agenda, played with cartoonish smugness by John Pais (voice of Raphael from the first Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles movie). He must not have had an inspirational violin teacher growing up because he's a little bitter and surly. As literally the only consistent personified force of contention Meryl runs into, he exists solely to be ridiculous (in the commentary Craven states that the character's not based on any person living or dead). Craven can't do comedy: focusing on the bumbling sheriff and deputy in Last House and turning Freddy into a smartass one-liner over the course of the Elm Street movies are admitted mistakes of his (the latter he corrected by making Freddy scary again in New Nightmare). But this character goes beyond bad comic relief, appearing in the movie so it can say "Look at this moron everybody – this is the just the type of guy who would be against the kind of revolutionary teaching fundamentals Meryl's presence at the school represents. What a boob!" But of course his unmotivated desire to see her crushed and humiliated goes unrealized, and Meryl continues bringing her fiddlin' fundamentals to class to the apparent benefit of these wayward adolescents.

The movie's chief antagonist is an envious colleague who doesn't cotton to Meryl's violin-teachin' agenda, played with cartoonish smugness by John Pais (voice of Raphael from the first Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles movie). He must not have had an inspirational violin teacher growing up because he's a little bitter and surly. As literally the only consistent personified force of contention Meryl runs into, he exists solely to be ridiculous (in the commentary Craven states that the character's not based on any person living or dead). Craven can't do comedy: focusing on the bumbling sheriff and deputy in Last House and turning Freddy into a smartass one-liner over the course of the Elm Street movies are admitted mistakes of his (the latter he corrected by making Freddy scary again in New Nightmare). But this character goes beyond bad comic relief, appearing in the movie so it can say "Look at this moron everybody – this is the just the type of guy who would be against the kind of revolutionary teaching fundamentals Meryl's presence at the school represents. What a boob!" But of course his unmotivated desire to see her crushed and humiliated goes unrealized, and Meryl continues bringing her fiddlin' fundamentals to class to the apparent benefit of these wayward adolescents.

Rosalyn Coleman gets the part of Token Angry Black Mom who removes her son from the class, explaining to Meryl in no uncertain terms that she doesn't want some lady teaching her son "dead white man's music." Meryl informs her that the kids are only learning to play "Twinkle Twinkle Little Star," what's the big deal? Yet only a few classes in and they’re already reciting Bach! Sure enough, when the son returns ten years later to support Meryl in her time of need, he's turned into the preppiest, most GQ-looking black man ever to come out of Harlem, complete with sweater vest. One of the themes of Craven's earlier films is that an assault by unfeeling, primal forces can awaken similar primal instincts in ordinary people, either out of retribution or pure survival instinct. What's more horrific: a group of murderous rapists and cannibals transforming boring, middle class folks into bareknuckle avengers who'll do anything to protect their family, or a white woman in East Harlem turning black kids into conservative yuppies?

Not that I'd ever accuse the movie of suggesting that the pinnacle of a young black man's success would be to become a successful white man. This movie's hip, yo – it opens with an Aaliyah song! It has black movie friends, like Waiting to Exhale. It knows what's up.

I guess Coleman realizes this because she soon warms up to Streep and things are going well when the movie cuts to ten years in the future.* Meryl's hair is a little grayer, she sometimes remembers to walk a little slower and she now has a Culkin kid, but looks as old as she did at the beginning of the movie. Apparently Craven can hire people to make it look like Robert Englund was burned alive inside a boiler room, but not to make Meryl Streep look any younger.

To make a very long story (over two hours!) short, budget cuts threaten to eliminate Meryl's violin class and her job, Chief Bassett has her hands tied, so supportive friends, teachers and boyfriends come together and arrange the fundraising "Fiddle Fest," where current and former students play with such luminary violinists as Itzhak Perlman and Isaac Stern (very famous.) Everybody loves it, there's a shot of the John Pais character in the audience crying because he finally believes in this crazy violin teacher. Backstage at Carnegie Hall, Meryl gives the troops a pep talk: "I want you all to take a second and just... breathe. Deep breaths. Now listen to me. I want you all to play from your heart. Forget about the audience, watch me, you'll do just fine. Just play from here." On the commentary, Craven reveals that Streep made up the line on set and her brilliant improvising inspired the title to be changed from 50 Violins to Music of the Heart. Just like how Last House on the Left was retitled from Sex Crime of the Century – make it more universal.

To make a very long story (over two hours!) short, budget cuts threaten to eliminate Meryl's violin class and her job, Chief Bassett has her hands tied, so supportive friends, teachers and boyfriends come together and arrange the fundraising "Fiddle Fest," where current and former students play with such luminary violinists as Itzhak Perlman and Isaac Stern (very famous.) Everybody loves it, there's a shot of the John Pais character in the audience crying because he finally believes in this crazy violin teacher. Backstage at Carnegie Hall, Meryl gives the troops a pep talk: "I want you all to take a second and just... breathe. Deep breaths. Now listen to me. I want you all to play from your heart. Forget about the audience, watch me, you'll do just fine. Just play from here." On the commentary, Craven reveals that Streep made up the line on set and her brilliant improvising inspired the title to be changed from 50 Violins to Music of the Heart. Just like how Last House on the Left was retitled from Sex Crime of the Century – make it more universal.

This "heart" business would be a deal breaker for me if I were actually invested at all in the movie or the character. Meryl's whole deal is that she teaches the children commitment and discipline by having them dedicate themselves to perfecting a difficult musical instrument, fine. But that's a mind exercise, the same kind learning to do literally anything would require: learning to ride a bike, or throw a football, or fix cars. The implication of musical spirituality that comes "from the heart" is entirely besides the point to what this thing is supposed to be about - it's a concept that is completely forced on the narrative and has nothing to do with anything. Putting kids through such a conformative process as being part of a violin group, having them concentrate on doing the same thing over and over, is not instilling in them some kind of poetic insight, even if it somehow inspires some of the kids to become better people (with sweater vests). They're giving themselves over to hours of difficult rehearsing and taking time away from other potential activities (the movie implies that said activities would be negative ones, running with gangs or smokin' crack, but there's every possibility that positive opportunities are also being missed), only to be told that Meryl has imbued them with some magical transcending purpose in life. It's an ignorant way to think, and arrogant.

If that's not a convincing enough argument that this movie has an ego the size of an octobass [that's the biggest kind of bowed string instrument - chris], check out the film's tagline: "She gave them a gift they could never imagine. They gave the system a fight it would never forget." Not as good, in my opinion, as "To avoid fainting, keep repeating: It's only a movie...It's only a movie...It's only a movie..." or even "Don't bury me – I'm not dead!" My question is, DO they fight "the system?" Nobody in the film really represents the system. This movie fails to include an Andy Garcia-in-Stand and Deliver bad guy come to rain on everyone's parade, so who exactly is in danger of forgetting this alleged fight that never happened? The only idea of some higher power looming over the school looking to undermine the fabrics of public education is through Meryl's angrily rants in front of family, students and in introductions to concerts that practically make her sound like a conspiracy nut. I got the feeling, from the film, that her attempts to "save the music" were not so much based on benefiting the kids as to keep herself from being unemployed. Wanting to save your job is absolutely reasonable, but masking that motivation under the pretext of "the children are our greatest resource" philosophy is a little dodgy. I'm sure the actual Roberta Guaspari's actions were more momentous in real life but as portrayed in the film it's got all the gravitas and significance of Max Fischer saving Latin.

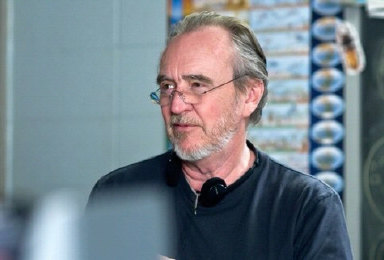

This kind of sentimentality doesn't become Craven, whose reputation is based on his earlier work's brutally honest portrayal of violence (Last House was a Vietnam parable, for instance) and his later slasher fare's reflection of the same. My take on Craven, which I've brought up a couple times in the past and still believe, is that he has absolutely great ideas which suffer from terrible execution. There's always something about his films that doesn't work: the terrible comedy and generally shabby filmmaking in Last House on the Left, the half-thought out "mutants" of the original Hills Have Eyes, the entirety of the movie Shocker [except for the last ten minutes! - chris]. But at the same time his films are smart, which makes me wonder why the hell he'd find himself involved with anything so dumb as Music of the Heart.

Craven is unabashedly proud of the film, as evidenced on the DVD commentary.** He starts the commentary track with producer Marianne Maddalena, who for some reason stops talking entirely ten minutes into the film. (Did she fall asleep? I hope Freddy didn't get her). "I was dying to do a picture outside of the genre," Craven confesses, seemingly obliterating all ambiguity over his main reason for doing M.O.T.H. "This is one of those movies of love that I've been waiting years and years and years to be able to do." Well that explains everything except what it was that could have possibly appealed to him about an inspirational script involving a violin teacher who plays by her own rules .

In his review of Music, Roger Ebert described Craven as "a cultured man who broke into movies doing horror and got stuck in the genre; he's been trying to fight his way free from studio typecasting for 20 years." Well, that's completely legit. If a director wants to break typecasting, or even challenge himself with material outside his comfort zone, that’s absolutely fine. But let's face it Wes, this is unacceptable. Munch never turned to positivism. Gyorgy Ligeti didn't write marching songs. There's a big difference between branching out and directng something that doesn't even exist within the boundaries of your own work, let alone an unapologetically cheesy Inspirational Teacher movie in which Meryl Streep at one point tells a crippled kid "you can stand strong on the inside."

In his review of Music, Roger Ebert described Craven as "a cultured man who broke into movies doing horror and got stuck in the genre; he's been trying to fight his way free from studio typecasting for 20 years." Well, that's completely legit. If a director wants to break typecasting, or even challenge himself with material outside his comfort zone, that’s absolutely fine. But let's face it Wes, this is unacceptable. Munch never turned to positivism. Gyorgy Ligeti didn't write marching songs. There's a big difference between branching out and directng something that doesn't even exist within the boundaries of your own work, let alone an unapologetically cheesy Inspirational Teacher movie in which Meryl Streep at one point tells a crippled kid "you can stand strong on the inside."

Several filmmakers commonly categorized as "horror directors" have tried their hand at something different. There have been successful attempts, like George A Romero's Knightriders, and less successful attempts that resulted in Dario Argento's Five Days in Milan and David Cronenberg's Fast Company. But those two failures in particular can be described as early slips by young directors still trying their voice, Craven was well into his career when he accepted this project. And for his part, Cronenberg is a filmmaker whose early films are textbook genre pics while his later work evolved into something absolutely unclassifiable; yet somewhat improbably, his whole filmography feels intrinsically connected. Couldn't Craven have found a non-horror project with themes that reflected his movies up to that point? Or has he been personally repulsed by the films he makes, secretly hoping that one day the right kind of safe, by-the-numbers Hollywood melodrama would come along?

As far as bearing the inescapable brand of "horror director," well fiddle me this, Craven – how come Sam Raimi wasn't compromised into making an Inspirational Teacher movie with Meryl Streep? You could argue that Raimi's guilty of shelling out a Nostalgic Sports Movie with Kevin Costner, but that's a perfectly legitimate side project for a baseball fan like Raimi, especially when your next project is something as good as A Simple Plan. How about Francis Ford Coppola and Joe Dante and other Corman protégées who started their careers with horror movies but moved on to other things? Steven Spielberg did Duel! Universally well-respected directors have managed to step in and out of the horror genre without being "trapped" by it, and come up with some of their best work: Neil Jordan, William Friedkin, Stanley Kubrick, Roman Polanski John Carpenter! Carpenter, the only man who I think rivals Wes Craven's influence and consistent contributions to the genre over the last four decades, has made amazing films that would never be considered "horror" by anybody (Assault on Precinct 13, Escape from New York, Big Trouble in Little China) yet reflect the filmmaker's style and interests and, most importantly, are anything but standard.

Craven should have taken a look at the career of Friday the 13th series veteran Steve Miner, whose non-horror projects include such fecal matter as Soul Man, Forever Young and Wild Hearts Can't Be Broken. These aren't the films of a respected filmmaker, they're soulless studio products brought in on time and on budget by a layman director. Granted, Miner's not nearly as talented or interesting a horror director as Craven, but that doesn't mean Wes could take a boring movie with cut-and-paste plot and bring anything to it. I'm tempted to just give up right now and blame this on straight-up senility; that reverting to a broader, more popularly-accepted genre at age 60 was just Craven's version of purchasing a midlife crisis dick car.

But Wes Craven is an intelligent guy. And a former college professor! He knows about all the stuff his fellow horror directors have done, and he's thought about it – I guarantee it. And that’s why I can't accept his excuse of "dying" to make a non-horror film. I don't buy that the creator of a franchise as successful as the Nightmare on Elm Street movies would have such a hard time breaking out of the mold, or that he got so old he didn't realize the blatant lack of sophistication inherent in this kind of story.

But Wes Craven is an intelligent guy. And a former college professor! He knows about all the stuff his fellow horror directors have done, and he's thought about it – I guarantee it. And that’s why I can't accept his excuse of "dying" to make a non-horror film. I don't buy that the creator of a franchise as successful as the Nightmare on Elm Street movies would have such a hard time breaking out of the mold, or that he got so old he didn't realize the blatant lack of sophistication inherent in this kind of story.

Maybe there was some personal connection he felt with the material? Let's explore that. He tried his hand at music before his filmmaking career started, appearing in Chicago cabarets with a guitar on his lap. Perhaps he feels an affinity towards string instruments. M.O.T.H.'s broken home subplot, there could be something there. Craven's parents divorced when he was very young, he himself went through a divorce with kids (in his book American Rhapsody, Joe Eszterhas claimed the divorce was a result of Craven's affair with Sharon Stone on the set of his film Deadly Blessing.) Superficially these aspects of the director's life could have drawn him to the material, but the guitar’s not a violin and I can't believe experiencing a divorce would bring him in touch with the female side of a difficult separation (which is just over-dramatized filler in the movie anyway.) Still, you could argue that Craven's filmography is full of strong women (A Nightmare on Elm Street, Deadly Friend - Kristy Swanson being physically strong in that one) and female victimization (Last House on the Left, Scream). It's possible he sympathized with Meryl's role as a struggling single mom. On the other hand, he already tackled the single mom bit in what I consider his best movie, New Nightmare, and it came off with a lot more honesty there.

* This is a weird coincidence: just by chance, I happened to review The Dead Pit for my “Video Oddities” series. In that movie, the evil undead surgeon returns from the grave after 20 years – the movie itself, from 1989, is 20 years old. In Music of the Heart, 10 years passes between the two parts of the teacher’s life – that movie is exactly 10 years old. What does it mean?

** My two favorite parts of the commentary: Craven is apparently very proud of an establishing shot of a tray of cinnamon rolls that took 20 minutes to shoot for some reason, and heaps praise on his actors in a classroom segment where he ends by adding "Even the dog is great in this scene!"

(continued on page 3 of Frustrating Filmographies #2: Wes Craven's Music of the Heart)

<<Previous Page 1 2 3 Next Page>>

home about contact us featured writings years in review film productions

All rights reserved The Pink Smoke © 2009