13 CURIOS FROM THE NEW CENTURY: part II

christopher funderburg

As the first decade of the first century of the new millenia draws to a close, I've already started to hear conversations about the Best Films of the Decade. For some reason the number of Best Films of the Decade is limited to ten, but that's all beside the point anyway because I've never really been one for patently ridiculous labels like "Best" and "Greatest" - there's just no point in arguing that sort of thing. But what I have been thinking about are all of the truly unique films that have been made in the last ten years, the works of le cinema valuable for their curiosity factor alone - doggedly offbeat projects with eccentric styles employed to express anomalous ideas for no readily discernible audience.

I ended up having a little more to say about each of the 13 films on this list than I expected, so I'm dividing it up into three parts (<<click here for Part I>>) to be published over the next couple of days. On the simplest level, I hope the list makes you aware of some films of which you've never heard, even if you don't come away as fan of any of the films I mention. Obviously, some of the films on the list are challenging or off-putting or smelly, but even more of them are lovably weird and genuinely worth your time - at very least, I think the world could always use a little more appreciation (and, heck, understanding) for these singular artists pursuing singular ends...

The Disappointment, or the force of Credulity

Named after a satirical 18th Century folk opera (based on popular hits including "Yankee Doodle") that so incensed its audience that they burned the theater to the ground after its debut, Brian Springer's debut feature is a meandering put-on so densely packed with facts, legends, rumors, history and outright lies that describing it as a "documentary" (as most critics have) seems a touch disingenuous. The film, of course, explicitly positions itself as a documentary, but that's all the more reason to find a different description. At any rate, deep down in its soul, this is a film that truly believes in the truth of un-reality passing over into reality - the line it divides between spirit and substance is blurred, for sure.

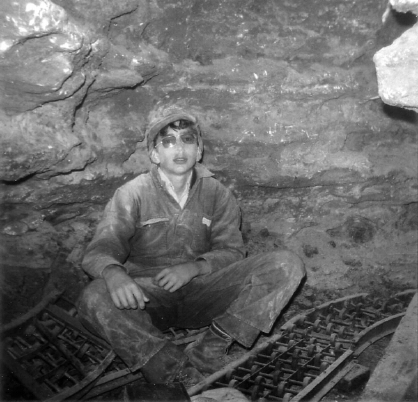

The film begins with the story of Springer's family, specifically their various treasure hunting excursions in rural Missouri. Over the course of decades, they hunted for the Spanish gold supposedly buried in the area and the film quickly makes clear that this perquisition isn't idle: these aren't under-funded chumps tooling about with metal detectors on their free weekends, they are serious searchers spelunking down deep in the cavernous cavities pocked across the countryside. It's been a fruitless search (for Spanish gold, anyway), but the film uses it as a jumping off point.

From there, Springer's twisting, constantly digressing narrative traces the roots of his family's quest for gold back to the 19th Century and finds a tangled web connecting anarchist Kate Austin, spiritualist folk lore and the titular opera, a wicked satire of intellectually dubious pursuits (like treasure-hunting and Spiritualism) with which the film is concerned. Over the course of the film, Springer literally and figuratively unearths strange sculptures of unknown origins, secret histories and a truly bizarre 120-page text purportedly co-authored by Springer's mother and the ghost of a Spanish priest. It, naturally, allows room for asides about the Korean war and etymological inquires.

At this point, I should mention that the movie is narrated by a large limestone sculpture that resembles some kind of a cross between a bug and a lizard. It sounds like it words are being routed through a "Speak and Spell" and the delivery of its choppy, declarative sentences adds a lot to the baffling air of the film. Its words seem both focused and pointlessly descriptive - enigmatic like a Sphinx, where every word feels carefully considered and direct, but ultimately puzzling. And that's the position of the film overall: I will tell you exactly what you need to know, whether you understand or not is up to you.

A charmingly deadpan riff on off-the-wall subjects, the film is also an extended rumination on the relationship between "history" and "discovery," but also between "folk beliefs" and "legitimate knowledge." I think that Springer ultimately sides more with the spiritualists and cranks on display (many of them are his family), but he's never strident or didactic about it. The film seems more intent on making its case by bringing you into a world casually brimming with ghosts, hidden treasure, revolutionary prophets and oracular folk art. With its loopy good-nature, the film easily disarms any natural resistance to such un-likelihoods - and any time you think you've got it figured out, it has something else up its sleeve.

Down with Love and Like Mike

Two big studio projects that are almost hard to believe exist, the true eccentricity of these films was carefully eschewed by marketing campaigns that positioned as completely normal Hollywood fair. Peyton Reed's manic recreation of Rock Hudson/Doris Day romps (á la Pillow Talk) would be a delightful film in any case, but its almost neurotic commitment to reproducing a candy-colored, fluffier than fluffy, decades-archaic style actually ends up producing a marvelously modern cinematic mutation of something long-since extinct. Maybe the most remarkable part is that the film retains the essential good-nature of those Hudson/Day films and never calcifies into something smug or arch.

Ewan MacGregor and David Hyde Pierce blow through their scenes with a carefully calibrated precision that only makes the proceedings feel more antic and off-the-rails: their back-and-forth is an expert contortion of one-liners, double-entendre, dry-comedy and campy self-awareness delivered with an unbelievable machine gun rapidity and jaw-dropping verbal dexterity. Rene Zewelleger, an actress of whom I in no way endorse or approve, delivers a climatic monologue that has to be heard to be believed: over the course of several minutes she displays an almost supernatural comedic touch in a monologue that combines an emotional reversal, a narrative climax and an outlandish plot twist. It's an outrageously absurd speech intended on one level to be absurd - its intricacy and length is essentially a riotous gag - but Zewelleger also delivers it as a legitimate tour de force.

Down with Love takes an aesthetic that was already fanciful to begin with and pushes everything (the sets, the costumes, the dialog, the colors) to the next level. It's a pasquinade of a caricature! It would be weird enough for more subdued homage to get bank-rolled and positioned as a blockbuster, but the fact of the matter is that the film quickly jumps past Pillow Talk into Frank Tashlin territory and then races from there into a heretofore unexplored beyond. Reed might've wanted to make one like they did in the good ol' days, but even in the good ol' days they never made them like this.

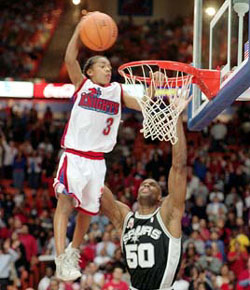

Another film churned out by the indifferent studio system, on the surface Like Mike is exactly what it appears to be: an Absent-Minded Professor rip-off that's both an extended shoe commercial and a star vehicle for a memorably obnoxious tween rapper. The plot ostensibly concerns a hard-luck kid who finds some Nike Brand Magic Sneakers that give him the skills to compete with the Goliaths in the NBA but director John Schultz instead lingers in a truly bizarre subplot revolving around a demonic orphanage impresario played by Crispin Glover. The film's heroes start out hopelessly exploited under Glover's cruel thumb, trapped in grotesque existence that's an outsized parody of Dickensian poverty. And the filmmakers are clearly more interested in Glover than anything else: the camera spends a lot of time in weirdly lit close-ups of his sneering, make-up-enhanced visage. Glover's notoriously unnerving presence several times threatens to completely disrupt the film and his monstrous subplot frequently overtakes the proceedings just when it seems like its finally fading into the background.

Another film churned out by the indifferent studio system, on the surface Like Mike is exactly what it appears to be: an Absent-Minded Professor rip-off that's both an extended shoe commercial and a star vehicle for a memorably obnoxious tween rapper. The plot ostensibly concerns a hard-luck kid who finds some Nike Brand Magic Sneakers that give him the skills to compete with the Goliaths in the NBA but director John Schultz instead lingers in a truly bizarre subplot revolving around a demonic orphanage impresario played by Crispin Glover. The film's heroes start out hopelessly exploited under Glover's cruel thumb, trapped in grotesque existence that's an outsized parody of Dickensian poverty. And the filmmakers are clearly more interested in Glover than anything else: the camera spends a lot of time in weirdly lit close-ups of his sneering, make-up-enhanced visage. Glover's notoriously unnerving presence several times threatens to completely disrupt the film and his monstrous subplot frequently overtakes the proceedings just when it seems like its finally fading into the background.

It seems pretty apparent that Schultz and his creative team (especially cinematographer Shawn Maurer and production designer Arlan Jay Vetter) are far more interested in exploring every nook and cranny of Glover's flamboyantly grim world. There’s certainly more effort and imagination on display in those contexts than in the endless, dull scenes of the tween rapper taking advantage of his magic shoes and slamming dunk after dunk. These two different worlds – the grimy Dickensian orphanage/sweatshop and the pro-athlete-cameo-heavy NBA ball courts – are spliced together with almost no consideration for matching their tone and look. When Glover encroaches on the NBA world (one that otherwise resembles normal reality), the results are just as disorienting as Jeff Daniels stepping off the screen in Purple Rose of Cairo or Christopher Lloyd dissolving the animated shoe in Who Framed Roger Rabbit?

Both Down with Love and Like Mike are infused with a certain flavor that belies their studio background: I suppose any filmmaker could've had the idea to make films like these two, but Reed and Schultz were given enough money that they could pursue their stylistic excesses down channels that simply can't be reached with huge budgets for elaborate set design, grotesque prostheses, extravagant lighting and fabulous costumes. Down with Love needs huge stars harnessing the full wattage of their star power to be so ebullient and exciting just as much as Like Mike needs a brain-dead, grossly commercialized kids' movie frame to be truly creepy and subversive. In some ways, this is the best argument in favor of a Hollywood system that thoughtlessly excretes garbage: neither of these films could have existed if some executive hadn't decided to make yet another Rene Zewellger romantic comedy or capitalize on the market synergies swirling around a flash-in-the-pan adolescent rapper and a sneaker company.

<<Previous Page 1 2 Next Page>>

home about contact us featured writings years in review film productions

All rights reserved The Pink Smoke © 2009