2007 YEAR IN REVIEW

john cribbs

Best

1. GONE BABY GONE

"When I was young, I asked my priest how you could get to heaven and still protect yourself from all the evil in the world. He told me what God said to His children: You are sheep among wolves. Be wise as serpents, yet innocent as doves."

How did this happen? How did spoiledactor/former tabloid king Ben Who-fleck manage to not only handle his directorial debut with admirable subtlety and grace but to deliver as involving and unpretentious an entertainment as Gone Baby Gone , the best crime film since Carl Franklin's One False Move and grittiest procedural since Jake Gittes walked away from Chinatown? To surmise that he got over himself (and stopped fucking Jimmy Kimmel) long enough to give room to the story and its characters feels like short-change: there's a deft hand at work throughout the film that gives weight to Dennis Lehane's tale of abduction and absolution on the grimy streets of Dorchester. Sure it features all the usual plot convolutions of the detective story, but inherent contrivances take back seat to character study as every lead tries to front and feint and find where they stand. The world Patrick Kenzie's trying to fit into, one of sordid dealings and ambiguous morals, is by far the most realized of any film in a long time: the people and locations reek with a collective veracity the silly plastic surfaces of Mystic River and The Departed wish they could have pulled off.

Speaking of the people, Baby's got great acting too. Amy Ryan's performance has been justifiably touted as star-making, but the entire cast (save Michelle Monahan, the film's weak link) is stellar. After years of goofy turns that risk turning them into permanent jokes, Ed Harris and Morgan Freeman are here given roles that remind us how good they can be when the material works, and John Ashton makes a welcome return. And at the center is Casey Affleck, who I predict will never be as good as he was in his two big films this year (just as I can't imagine lightning striking twice for brother Ben in the director's chair.) His Kenzie is the most vulnerable PI ever put on screen, a guy whose idealism is given a naked trial by fire as he gets closer to the truth, that defending the defenseless isn't as clear cut as it should be and nothing is what it seems. And honestly, in a world where Ben Affleck directs the best movie of the year, what is?

2. SILENT LIGHT

"A brave man makes his destiny with what he's got."

It may seem somewhat vulgar to follow up a movie as modest as Gone Baby Gone with what is probably the most unapologetically indulgent art film I saw all year. But what a rich, hypnotic, slow-moving roller coaster it is! With Silent Light, Carlos Reygadas shows he's just as interested in applying his austere approach to simple anthropological melodrama as he is to the edgy, baiting material that's netted him the reputation as a Mexican enfant terrible. With an opening shot that would make Terrence Malick weep and break apart his dolly tracks, Reygadas introduces the audience to an order of Mennonites living in Chihuahua and the cinematic world to the beautiful language of Plautdietsch, a Dutch/German dialect that seems to linger in the room even as asentence is abruptly ended.

Borrowing the style (albeit a bit glamouredup) and story from Ordet, Reygadas finds transcendent in the mundane, but there's something else going on. Rather than asserting the ascetic purity of a simple life, the characters suffer the dichotomy of human nature vs spiritual destiny: whether the beauty of the world around them strengthens the will or merely exists as a cold stasis of confinement. If god demanded a pure and penitent life, surely he wouldn't imbue temptation into the fabric of the natural world! The film recalls Tarkovsky and Olmi as much as Dreyer, but Light's use of sight and sound feels like an advancement of what's come before and plays out in a form that's uniquely Reygadas, who reveals that even in paradise people can create their own torment but they can also reach beyond the confines of society and, ultimately, the laws of corporeal captivity. Personally I can't wait to see it on the big screen (I've only watched a screener) two or three times.

3. BEFORE THE DEVIL KNOWS YOU'RE DEAD

"The world is an evil place. Some make money off it, some are destroyed by it."

I hate using the word "Shakespearan" in reference to anything, but thatmight be the only term, literary or cinematic, epic enough to describe Sidney Lumet's nasty little melodrama. Back in New York where he belongs, the 83-year-old vet blows the new kids out of the tank with a risky, invigorating construction only a master filmmaker could pull off, knocking out the twist early, playing around with viewer expectation, lingering comfortably in long takes shot on DV and, in his boldest stroke, overlapping time and replaying scenes through different perspectives. This excellent use of fractured timeline is never showy or indulgent: every repetition of a scene reveals something, whether it's as small as a character reaction or as big as a major plot turn. But Lumet doesn't let it get gimmicky. Kelly Masterson's script is sustainable enough that the director can probe and reconfigure whileexpertly maintaining the tense momentum of the story.

The film's amasterpiece of editing work, but also a stunning achievement in structure and framing: Phillip Seymour Hoffman's self-loathing Andy is always looming over Ethan Hawke's weak Hank, who in turn is relegated to being cornered or pushed back into most of the shots in which he appears. To top it off, Lumet reminds us what a great actor's director he is, eliciting great performances from everyone. Hoffman, Hawke, Albert Finney, Marisa Tomei and small players like Amy Ryan and Michael Shannon (who are pretty much my homecoming queen and king of performers this year) and Aleksa Palladino, all top-notch as a collective of repulsed and repulsive desperate liars and cheaters whose every action proves more condemning than the last. Though not without its convolutions (the infidelity subplot seems a little much), the film turns the standard heist thriller/family tragedy on its head and, if I remember correctly, ass-rapes it a few times. More than a return to form, Devil stands up next to 12 Angry Men, The Pawnbroker, The Hill, Dog Day Afternoon and Network and even manages to show them up more than once. In short a return to fierce filmmaking: angry, living cinema.

4. STUCK

"Why are you doing this to me?"

Stuart Gordon seems to finally be getting some long-deserved use out of thelittle pieces of respect he's accumulated over the years and last year was a geyser of Gordon masterpieces for me. I finally saw the hugely underrated King of the Ants, his two great "Master of Horror" episodes (from a series I don't largely consider great) and this, which of all my favorite movies of 2007 I'm most jealous. Based on the story of the Ft Worth woman who hit a homeless man with her car and left him impaled through the windshield in her garage until he died, Stuck is one of the sharpest black comedies in recent memory. Gordon taps into a vengeful rage at callous insensitivity, and his main target in the film is nothing less than the incongruity of human indolence (Paul Haggis, take note you hack!)

Mena Suvari, also credited as an executiveproducer, gives her best performance by far as the frantic driver and Stephen Rea's hangdog face is perfect for the beaten-down victim struggling to survive, whether it's bolting from his angry landlord with as many clothes as he can carry or dislodging a windshield wiper from his abdomen. The movie has as many hilarious visual gags as it does exhilarating suspense pieces, but what itís loaded with is boldly excessive, darkly madcap mayhem that is riveting to experience (the TIFF audience ate it up, best audience response I've seen in a while.) It could have easily been called Struck - or Crash - but that wouldn't fit the level of giddy absurdity Gordon reaches. Scott Tobias said "too bad there's no place for a movie like Stuck in American theaters these days," and I can't help agreeing. Do they even deserve it?

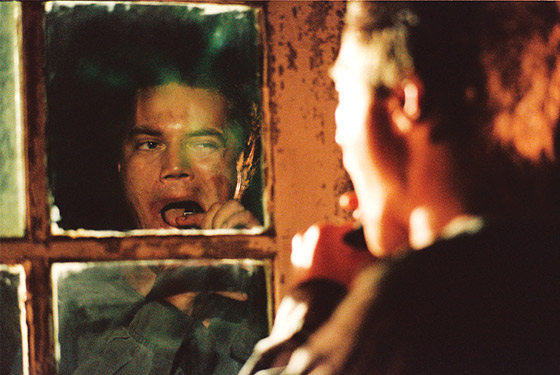

5. BUG

"Why are you doing this?!"

Chock it up to bad marketing on the studio's part: this year Billy Friedkinmade a great film for the first time in twenty years and nobody even noticed. Adapted by Tracy Letts from his play, Bug is a love story for the delusional parasitosis patient in all of us. And before you think "Oh no not another drama about a schizophrenic ex-soldier with delusions of insect infestation," take into account the homerun performance by Michael Shannon, who sells a terror of invisible critters and the seductive folie ŗ he works upon Ashley Judd with above board intensity. Friedkin has sneered at the film being sold as a horror movie, but the label isn't far off: he's certainly tapping into Cronenberg territory (Shannon's freakout in the bathroom mirror is Brundlefly-esque) and the confinement horror of Polanski's apartment trilogy. The latter is especially evoked by the off-white walls turned black-lit quarantine of the hotel room where the characters redirect the source of their hopelessness to a more tangible, government-funded mindfuck that turns them into the satisfied (and, suddenly, important) victims of an unbearable humanity. What could be scarier than relegating oneself to that? Tainted by the condition of the country they live in, its global politics and commodifying of citizens, Shannon and Judd need to get "bugged" if only to justify their own cruel experiences, concluding that life is such a sordid mish-mash of fear and despair we might as well combine and condense those anxieties into microscopic parasites in a manic struggle to escape anatomical destiny. Cynical it may be, but it's kind of beautiful.

6. SAD VACATION

It's good to see the spirit of Shohei Imamura lives on in the films of a newgeneration of Japanese auteurs like Shinji Aoyama. In his modern Greek tragedy, Aoyama works with a loose structure that's also deceptively intricate and complicated. In his deceptively airtight concept-premise, a former crook (the great Tadanobu Asano) quits his dead-end job transporting immigrants for slave labor to form a surrogate family of his own and thus build an artificial comfort zone within which he can remain, happy and anonymous. But fate deals him an unexpected hand when he discovers another surrogate family: a taxi company run by his estranged mother, a woman who abandoned him as a child and may be theone to blame, and repay, for his sordid past.

I'm going into detailabout the plot because I'd love to get people interested in seeking this movie out, as Aoyama hasn't had the best distribution track record (thematically-linked earlier films Helpless and Eureka are almost impossible to find.) He has an excellent understanding of the suffocation caused by family ties in Japan and the amoral lengths characters are willing to go, using their tainted past as an excuse to ruin their future. In a rigidly-structured society the "ideal" family can only be destroyed by true blood relatives and individuality ultimately crumbles. Vacation features multiple characters: determining their relationship to each other is part of the fun, but I found myself emotionally involved in all of them and each little journey leading to the quitely unnerving, ambiguous ending. What Aoyama's most interested in is what we do with our life and who we choose to share it with, whether it's taking the initiative to hunt down the charming local girl who disappeared or indulging in the most uncomfortable mother-son closeness since The Grifters. Escaping destiny seems to be a heavy theme in the best movies I saw this year (and there's more of that coming up!) but this one nailed that hopeless concept on the head.

7. EASTERN PROMISES

"Sometimes if doors are closed you just open them up."

"Promises PROMISES super-thrills and boney-chills!" - John Cribbs

While not exactly the one-eighty return to form from the horribly disappointing History of Violence, Cronenberg's latest still feels like a stronger sister film, one that improves on similar ideas and is far more successful in execution. For one thing, the violence is more vivid, soaked into the celluloid - visceral (a word associated with the director's best work.) Appropriate to a narrative driven by the diary of a dead girl, Promises exudes an elusive terror through the quiet threat of the vory v zakone, clandestine boogeymen in sweatervests who'll snatch unsuspecting girls out of the east into a life of prostitution and death. And from the initial killing in the most unlikeliest of places (a barber shop - top that, Sweeney Todd) everything is dug up from beneath the surface: London subcultures, secret societies, casual prejudices, hidden identities and nothing, no matter how many frozen fingers youcut off, stays buried.

The ritual of initiation and weight ofobligation is upon every character from Naomi Watt's reluctant sleuth of a midwife to Vincent Cassel, guilty simultaneously of sibling rivalry and unacceptable homosexual desire for Viggo's butcher. Cronenberg's technical team - Suschitzky, Howard Shore, even Denise (great costumes, Denise) - are at the top of their game and the man himself is back in friendly waters. Mortensen's grisly tats recall the "prophetic roadmap" markings of Elias Koteas' crash fetish Vaughan, and that's not the only hark back to the director's best work: Promises is every bit the baroque chamberpiece as Dead Ringers, as much the Noh tragedy as M Butterfly. But mainly it's thrilling pulp-art and a great action film, all this encapsulated in the best scene - possibly of any movie this year - the (literal) balls-out knifefight in the bathhouse. The ending's a letdown: although I like the structure of Viggo "exposed" after his naked throwdown, I'm surprised the last scene didn't have Ludacris letting all the whores out onto the street murmuring "Dopey crack-hos." Still, the worst scene is better than the best scene in History of Violence, and a step back in the right direction.

8. PERSEPOLIS

It's sort of a miracle how well Marjane Satrapi, with co-director Vincent Paronnaud, was able to rework and revitalize her excellent comic strip on the screen. Artwise it's a gorgeous mix of German Expressionism and Lotte Reiniger's Orientalist animation, part Chinese shadow theater part UPA cartoon, gorgeously layered and charmingly drawn. The art is compelling and the screenplay deserves it: what could have been ethnographic agitprop is instead simply a great coming-of-age story. Beyond the prejudices against her background and persecution Marjane suffers for her independence, she experiences the universal pangs of being a teenager and a young woman. It's hard to say whether she goes through a more difficult time under the reign of the Shah, stripped of identity and individuality during the Ayatollah's fundamentalist revolution, or during her first relationship with a boy after leavingPakistan for the west.

All of these life changes she faces with charming aplomb (that's right I used the word aplomb, I'm not ashamed of it) and we're with her every step of the way. Even under the hijab she's relatable: just compare her rebellious, Bruce Lee-loving outsider to Ellen Page's Juno. I believe her love for Iron Maiden more than I bought Page's Mott the Hoople name-dropping. What's more lovable, a trendy hipster spouting nonsense colloquialisms or Marjane headbanging defiantly on her tennis racket guitar to Maiden-esque metal in her own free world? (Yeah I know itís a little early in these lists yet but fuck Juno man.) All apologies to Brad Bird and Ratatouille, which I loved, but this is the best animated movie of the year: the political history of a country through the eyes of rebellious youth.

9. IMPORT/EXPORT

From the cold European no-escape subgenre of foreign releases comes Ulrich Seidl's latest, a surprisingly sensitive, often hilarious story about two characters searching for a little common decency and respect but encountering only dehumanization and indolence. Unemployed mother Olga from Austria and aimless security guard Paul from Ukraine swap places without ever meeting and without an idea what it is they hope to find. Truth and beauty? A dignified life? What they find isn't too different from life back home: humilations from absurd porno webcam companies, troll-like gypsys, callous thugs, scumbags with childlike indifference, self-righteous middle class families, murderously jealous co-workers, lecherous thieves and some stuffed animal teeth that need cleaning.

Almost neorealist in its settings (it features the most claustrophobicopen spaces put on film since Kieslowski), the movie's not without humor. Like his contemporary Lukas Moodysson, Seidl is able to poke fun at his characters and their banal situations while avoiding exploitation: there are numerous opportunities to get cheap laughs from hapless foreigners and the declining patients of a geriatric hospital wing but Seidl never takes advantage of his non-professional extras. As a result the acting is great. Stars Paul Hofmann and Ekateryna Rak are so good it's amazing they've never been in front of the camera before. One of two movies beautifully shot by camerman Ed Lachman, the film's not quite as groundbreaking as Seidl's 2001 Dog Days, but it's a better movie all around, a sad and funny study of labor migration and human spirit as global commodity.

10. 3:10 TO YUMA and THE ASSASSINATION OF JESSE JAMES BY THE COWARD ROBERT FORD

"I ain't never been a hero."

"I've been a nobody all my life."

All new westerns are saddled (no pun intended) with the compulsory acclaimof "saving" the genre from celluloid oblivion, a dispensable obligation forced upon them by critics who don't seem to realize they never went away, that their influence exists in everything from modern crime movies to John Carpenter action films. Just because nobody's wearing a cowboy hat and riding a horse while shouting "yee-haw" doesn't mean it's not a western. In these two movies the characters do wear hats and ride horses, though I'm pretty sure no one shouts "yee-haw." That's post-modernism for you, although what you've got is your classic non-gay cowboys (well, arguable in the latter) in films that had seemingly unsurpassable acts to follow: the original 1957 3:10 to Yuma and Samuel Fuller's I Shot Jesse James. The new Yuma, from the director of Walk the Line and writers of Bart Freundlich's Catch That Kid, had everything going against it not unlike Christian Bale's obdurate Dan Evans. But despite a handicap akin to missing half a leg, James Mangold and company manage to do exactly what someone who feels they just HAVE to remake a near-perfect classic should: they stay true to the original idea and up the ante in exciting, suspenseful ways. Honestly, this is the John Carpenter's The Thingof westerns (didn't mean to bring up Carpenter twice, it just sort of happened.)

Meanwhile, Chopper's Andrew Dominik managed to spin contemplative gold out of Ron Hansen's fictionalization of the last, less glorious days of Missouri's most-loved killer. What both films share are men engrossing in their unsavory deeds and men pitiful yet identifiable in their desperation. They're about men who got something to prove, one to his family and the other to himself, and each have to do it in the shadowof a charismatic psychopath of an outlaw.

But mainly what they share is an understanding of the bleak, uncivilized world of the western, the unsavory abandon of lawlessness, and how small a man can be when he's lost in it. Evans and Bob Ford make their place in history by getting close to a legend, and learn that when the legend becomes fact, you shoot the legend (or send him off to Yuma.) Neither film hits it out of the ballpark - I could do without the ending of both of them - but they're full of brilliant scenes and beautiful photography (Roger Deakins deserves co-directing credit for his work in Assassination) and overall a clear portrait of what brings a man to his most desperate decision.

11. NO COUNTRY FOR OLD MEN

"OK...I'll be part of this world."

Patient fans of the Coen Brothers have earned another great film, and we get something approximating a great film in No COuntry for Old Men, which on one hand seems almost effortless in its technical ingenuity and, from a writing standpoint, a whole new territory for the possibilities of adaptation. Cormac McCarthy's blood opus is not so much retold as interpreted with meticulous zeal through the eyes of twin visualists of the darkest whimsicality. A modern western (that's right critics, no horses and no hats...well that's not true but you get the idea) as well as a horrific road movie, Country could be confused with a bad dream if not for the vividness of its open fields, the thundering echo of a tent pole against the walls of a vent that's so reminiscent of the dragging shovel in Blood Simple.

Thisis the Coens at their most serious since that masterful debut, and their progression as more vocational filmmakers has for better or worse finally met material deserving of such diligent craftsmanship (craftsMENship?) In the absence of Carter Burwell's score we have the violence, which falls from crescendo to calando through the film's running time and perforates the silence like...well, a gunshot. Once again you've got Roger Deakins, who shoots roadside motels at magic hour like no other cameraman. The interpretation and movement of McCarthy's characters into slouching, sad-faced Tommy Lee Jones and Bardem's demonic auton Anton Chigurh feels like creation rather than moving storyboards. And that ending, for all the complaints, is pretty goddamn perfect (later you'll see I'm against perfection, but for now let's just say this movie worked for me.)

Worth Mentioning: The Lookout

"Whoever's got the money's got the power."

Since this is his second year on the "worth mentioning" list, I'm starting tothink that Joseph Gordon-Levitt must be an actor worth mentioning (if I had liked Mysterious Skin in 2005 he'd be sweeping: to be fair, I liked HIM in that movie, and this year Gregg Araki made his best movie to date so apparently everyone's improving.) He certainly carries this little drama/heist thriller with his performance as Chris Pratt, former BMOC turned brain-damaged town idiot. How he deals with the debility and lays out his day-to-day agenda become fascinating thanks to a solid script and tight direction by Scott Frank, who already has things feeling odd and menacing before the villains showup.

The movie's got problems - mostly in the form of blind, obnoxiousJeff Daniels - but is unique enough to make it impossible to discard, and at very least is a hugely promising start for Frank as a filmmaker. Lookout is the anti-Memento, relying on story rather than the twists that can easily be milked from the gimmick of its hero's weird mental illness. And Gordon-Levitt: his performance is the anti-Daniel Day-Lewis, and I'll apologize in advance to the DDL lovers out there but JGL plays it subtle, and I hope he never tries to go the showy/scene-appetite route. I'll say it again, he's become an actor worth mentioning and I almost don't want to because I feel we need to keep him to ourselves. Martin Scorsese, leave our JGL alone!

Best 2006 Movie I saw in 2007

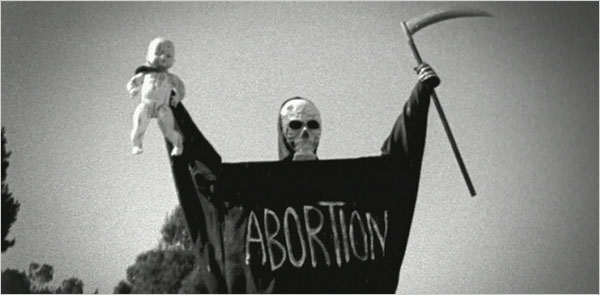

Lake of Fire

I'm usually not a fan of the shady documentary medium, but there were plenty of notable "real life" entertainments this year. Plenty of political docs as usual, but the most interesting controversies came from the alleged wunderkind of My Kid Could Paint That and the shifty politics of video game champs in The King of Kong: A Fistful of Quarters. Errol Morris-acolyte Jason Kohn deserves praise merely for setting foot inside Brazil's Sao Paulo to film Manda Bala, described by its director as a "nonfiction Robocop" and featuring, among other things, stories from a surgeon who grafts ears back onto kidnap victims. Philip Groning unveiled the quiet lives of Carthusian monks as literally the first ever outsider allowed inside their walls with Into Great Silence. Terror's Advocate, a nice companion piece to director Barbet Schroeder's own General Idi Amin Dade, opens with its subject downplaying the genocide of the Khmer Rouge and just gets more audacious from there. Moving from more sympathetic causes (the Algerian resistance) to undefendable butchers (Klaus Barbi), the film asks what kind of terrorism is justified and what kind of man would stand by it, providing one of the best lines from any movie this year: "I would even defend George Bush if he pled guilty."

But the best doc of the year (technically from 2006) is Tony Kaye'ssixteen-years-in-the-making abortion epic Lake of Fire, an examination of all the major political issues from both sides (Kaye himself has stated he's not sure where he stands.) The terrorism of pro-lifers is portrayed in all its extremism - it's chilling to watch a doctor demonstrate his bulletproof vest then see pictures of him shot through the side slumped over the wheel of his truck, the vest hanging uselessly around his torso - but there's also the sense of loss in an extended sequence of a woman going in for a procedure. Coldly ambivalent yet strongly humanistic, what more could you want from a documentary? I'm curious to see Wrath of the Gods, an Overnight/Lost in La Mancha examining of the classic Canadian film Beowulf and Grendel.

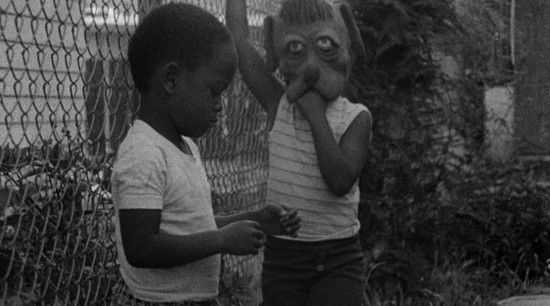

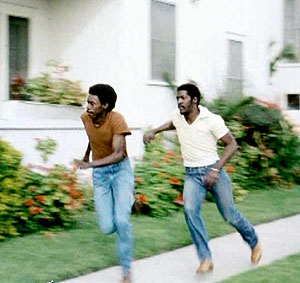

Best re-release

Killer of Sheep and My Brother's Wedding

With the almost miraculous release of Charles Burnett's 1977 Killer of Sheep following last year's American debut of Melville's Army of Shadows, I'm starting to wonder how many more masterpieces they've got locked up in a trunk somewhere. When I talk about Sheep, I feel like I'm referring to something timeless: that of all the films ever made in America (and maybe even around the world) it deserves a top slot on a list of movies that should be regarded with the ageless classics of art, literature and music. But since I've talked it up and down over the last year, I'll stick to something brief about Brother's Wedding. While it's not in the same league as Sheep, it'll always have that second feature label of "lesser work," it's a great film just as worthy of discovery. You don't have to be a put upon 30-year-old dry cleaner living with your parents in the Ghetto to feel for Everett Silas' Pierce, a man ultimately torn between two ceremonies that stand for two very different sides of his life and represent the first real decision he's ever had to make. More story-oriented yet just as quietly observed as Sheep, it continues Burnett's theme of a man's responsibility to family while struggling to remain true to himself in an environment where survival's tough and fronts areimportant.

Whereas Sheep is poetic, I think of Wedding as wise: its characters can't help but feel the constraints of who they are, where they come from, and there aren't any transcendent slow dances with a loved one for them. The honest ones lead their life and refuse to make fake appearances for those who've moved away from it in shame, something that's easy to do until an actual line is drawn and opportunity demands the right choice be made. Both films have great ideas and plenty of hilarious moments, character quirks like Stan defending his incoming by stating he gives to the Salvation Army and the little girl who makes herself up to try and impress Pierce in his mother's dry cleaners. Wow, these movies are great. Now can we please get a release of The Annihilation of Fish?? (I mean the title has another animal getting whacked, it must be just as good.)

3 movies I had the most guilt-free fun at in 2007

Hot Fuzz

Spiderman 3

The Bourne Ultimatum

(continues on next page with The Worst of 2007)

<<Previous Page 1 2 3 Next Page>>

home about contact us featured writings years in review film productions

All rights reserved The Pink Smoke © 2010