2008 YEAR IN REVIEW

john cribbs

The Best

1. A Christmas Tale. I spent a lot of 2008 with my family, so it was funny that the big theme of many of the year's great films turned out to be "family maelstrom." That theme was fairly prevalent in some of my favorite flicks from 2007 (Before the Devil Knows You're Dead, Sad Vacation) but none of those touched upon it centrally the way at least three of my top ten did. To cite the "actual quote from George Bush" that opens Step Brothers: "Families is where our nation finds hope, where wings take dream." If there are any wings taking dream in this film, they're the kind that spin you around and dash you against the sharp rocks by the sea. Our first victim is Henri Vuillard, brought into life to serve as potential donor to a first born son and subsequently neglected after his marrow is deemed non-compatible.

Many years pass and the chance for reunion, just in time for the holidays, appears when it's revealed that his mother Junon has been diagnosed with the same fatal disease and from which he could potentially save her. But years of bitterness, disappointment, tightly formed alliances and exiles have molded the Vuillard clan into an unstable society brimming over with old secrets and crushing resentments.

Arnaud Desplechin, whose Kings and Queen was excellent but in no way hinted at the heights he achieves here, is a filmmaker whose intuitive talent for blending drama and sporadic comedy along with complicated subplots creates a free-moving feel which is at the same time deeply textured and highly entertaining. The film is constantly surprising, in everything from the eclectic choice of music to stylisic flourishes like letters being read directly into the camera, and so well observed that it's always interesting and never overbearing. That's because Desplechin cares about the Vuillards, warts and all: a phenomenal cast spearheaded by Mathieu Amalric as Henri and Catherine Deneuve as Junon play them as if they've just stumbled out of burning car wreck: weighed down by the impacted metal of familial obligation. Instead of reuniting with the family as a source of comfort and security, they trudge hesitantly onto the battleground of understanding.

What's amazing is how after two and half hours of exhausting emotional warfare, the movie still ends on a sweet note, with the idea that family in all its ugliness is still family. There is no resolution and never will be, only a series of confrontations and accusations, for Desplechin knows that not only is every unhappy family unhappy in its own way, it sets its own cadence: all-out disaster becomes their personal tradition. I get kind of annoyed reading reviews of the film that compare it to "dysfunctional family Christmas" fare like Four Christmases and Nothing Like the Holidays, but the alleged humor those movies wring out of family gatherings is as witty as it is cringe-inducing in A Christmas Tale, particularly Amalric's aggressive yet humorously pathetic grapples – both physically and verbally – with family members. Not only the best film I've seen yet at the Toronto Film Festival but easily one of the best and most refreshing released in the last decade.

2. Happy-Go-Lucky. In a way this is the movie Mike Leigh has been working up to his entire career: a film that balances his appreciation of carefree, eccentric working class characters with the doom inherent in his cynical denigration of the world they live in. Using his fascinating (and cryptic) collaboration process, Leigh has helped Sally Hawkins find Poppy, a tireless optimist who would laugh like a 6-year-old if you referred to her as "cock-eyed" and look at you cock-eyed if you compared her to Candide.

The first impression of her is that she's obnoxious, the kind of ditzy twit with mouth diarrhea you can't stand to be around, but when she finds her bike stolen and cheerfully laments "We didn't even get a chance to say goodbye!" it's obvious her bright exterior isn't some defense against other people, it's just who she is. How Leigh presents Poppy – as always, with a caring and uncritical eye – is not so much an indomitable spirit as a woman who hopes for the best and responds to every situation as if that's exactly what's been offered. Leigh has said that the difference between Poppy and David Thewlis' Johnny from Naked is that Johnny is disappointed, whereas Poppy is willing to give life the benefit of the doubt.

In her bright clothes and winning smile, she seeks only positive qualities in others and confidently challenges the world to shatter her optimistic assumptions. The challenge is met in the form of Scott the driving instructor, a bundle of fear and disgruntlement beautifully acted by Eddie Marsan as Johnny without the height, wit or modicum of sexuality. You won't find better scenes this year between two actors than those of Hawkins and Marsan in that car together, where Scott's spewing vitriol at the human condition clangs against the impenetrable wall of Poppy's good nature.

In between are sketches featuring the same kind of weird and dodgy people that populate the director's best work, viewed by Poppy in the environment in which they've sheltered themselves (an apartment, a dance class, under a bridge.) Like Leigh, she doesn't judge anybody: she wants to speak and understand and help any way she can. It's not by design, and it's not something she's aware of, but it's something that's brought out in her. Poppy is not happy, she's not lucky. She's someone Mike Leigh has spent thirty years trying to create – a good person.

3. The Edge of Heaven. Seeing Fatih Akin's new film was like running into the Fatih Akin I knew from Head Onin a bar somewhere. I hadn't seen him in so long, and on first glance I immediately noticed a change. He was still the same guy, with the same fascinating view of the world I remember, but he's matured into someone less angry, even somewhat accepting, and has clearly let himself be effected by it in a positive way.

I don't say that to knock Head On, which remains the most provocative breakthrough film of the decade, only to point out that its director hasn't limited himself to aggressive filmmaking. The Edge of Heavenfeels like a work by someone much older, more a reflection through rather than a suicidal collision with the randomly distributed shards of fate. The taste is still bitter, but cleansing: for Akin, modern life is cruel and circumstance is a horrible bitch, but what dealing with it makes of us is something achingly pure.

In a gorgeously structured narrative the connections between two mothers, two accidental murders and two people looking for someone they'll never find comprise a braided narrative held together by the common thread of a search for personal identity in the current state of the world (specifically Turkey and Germany.) Whether the search be driven by a perceived purpose, a political stance or the love for another person, each will lead its seeker to a new sense of understanding. Their place in the world and the perception of others may have confined them to their miserable fate, but the difference between allowing themselves to be victimized and giving themselves over to others is what ultimately determines their destiny. It may be the only film I've seen in the last few years to succeed despite tackling so many Big Themes: watch this film next to Babeland see which one has more to offer than a vague sense of association.

It says a lot about how great the year was that anything could be just as good if not better than this film. The third act closes with the most sobering and poignant symbol of acceptance I can remember in a film. It's appropriate that the best performance in a roundly stellar cast comes from the great Hanna Schygulla, since Akin may be the closest thing we have to a Fassbinder these days: a wildly-talented provocateur plunging headlong into the politics of brutality and tenderness.

4. Paranoid Park. "What happened?" is exactly what Gus Van Sant plans to flirt with from the first shot of this third entry into his outstanding Death Trilogy (Gerry's more of a dress rehearsal), one that's sort of a spectacularly underplayed spin-off of Elephant. We follow a kid with a skateboard in frames so moodily lit and tracking shots so hypnotically precise that it's ten minutes before you even think to question why exactly we've been following him. Teenage angst is something so ubiquitous it's hard to convey on screen without completely deemphasizing it, yet as in his masterful 2003 film Van Sant forms such a mysterious and romantic surface out of the stuff we want to break into it like a safe and find a solution to all this stoic ennui.

His Weltschmez hero Alex is a skater, and while he doesn't run into any of the Salvies from Larry Clark's Wassup Rockers, he experiences a night filled with the same sense of dreamlike dread in Portland, Oregon as the day those kids tried to escape from L.A. But Van Sant only offers pieces of that night, mostly made up of skateboarding scenes shot in a way skateboarding scenes are never shot, spending more time with Alex as he suffers silently alone, his complacency in a tragic accident lulling every existential responsibility to the surface: his true feelings for the popular cheerleader he's dating, what he might have done to make his father leave home, how much he should care about what's going on in Iraq. The incident at Paranoid Park has awakened his sense of place in the world, and the entire movie has the exploratory innocence of a newborn child. No redemption is offered, only the chance for Alex to look at himself and ask, What happened?

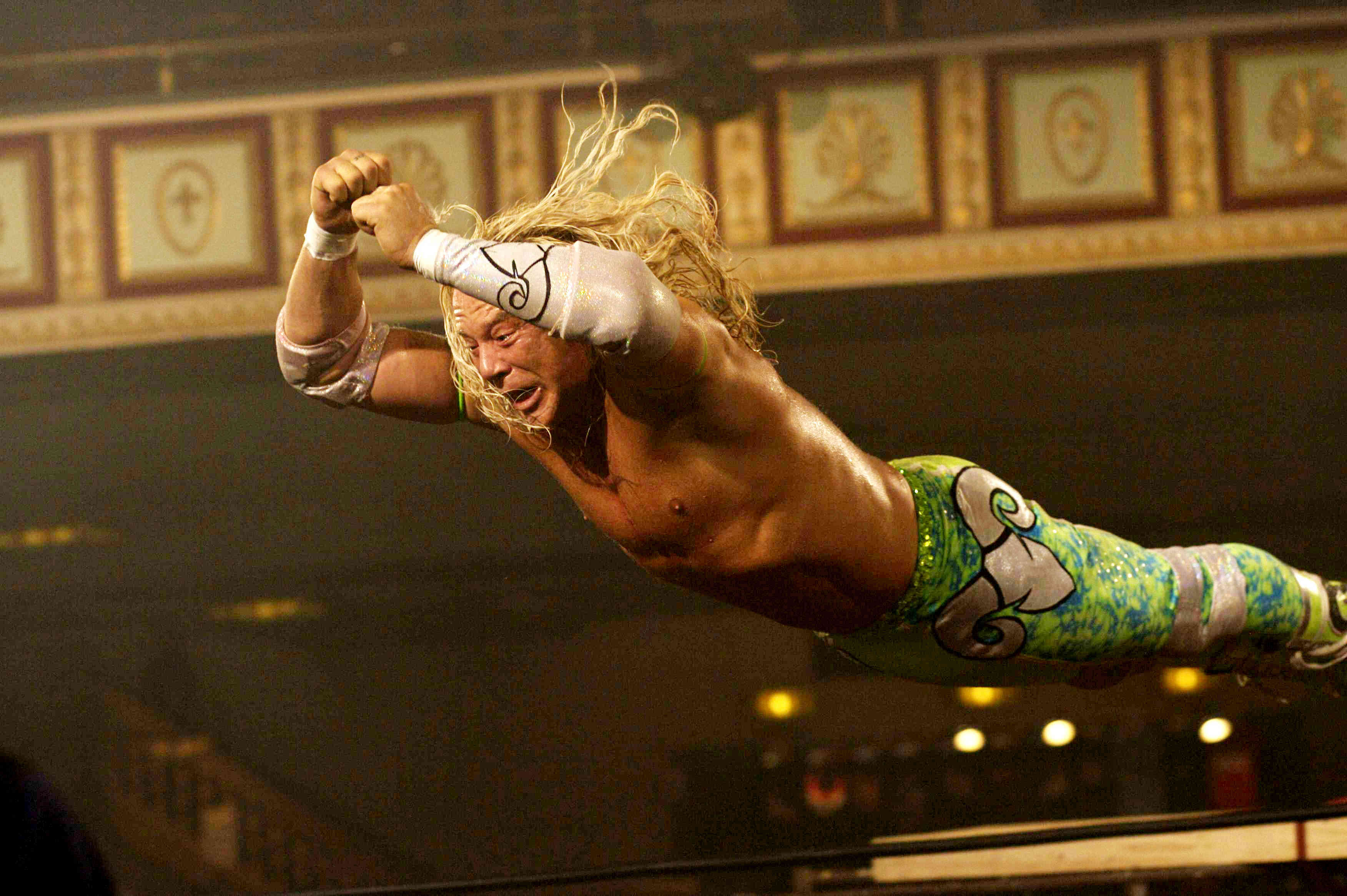

5. The Wrestler. Is pro wrestling real? I thought it was staged, but after seeing The WrestlerI have to wonder. If Mickey Rourke's Randy "The Ram" Robinson wasn't really getting beaten to death every day in the ring for 20 years, how do you explain the "used up piece of meat" that now drives his van and lives in his trailer (when it's not padlocked), wears his hearing aid and pops his vast amount of pain pills? Who has to continue submitting to the hard-slamming, sometimes nailgun-enhanced gauntlet of the ring for the dwindling amount of hardcore fans hooting and crying out for actual blood? Even as he choreographs the moves backstage with his fellow friends and fighters, or just relaxing on the couch watching TV, Randy looks like there isn't one part of his body that isn't in pain. So where did this guy come from?

I loved The Wrestler. It deserves strong consideration for best movie of the year for, among other things, using the instruments of filmmaking to communicate a story that's worth telling (what a novelty!) That said, it would be impossible for Darren Aronofsky's movie to be any better than Rocky Balboa(which is also a great movie, to be fair) or come anywhere near the extraordinary film it is without two things. One of them, obviously, is Rourke. Without him, the film would not even register, it would be a "Wallace Berry wrestling picture." Rourke's performance makes me want to describe it using all the bullshit I hate hearing about any acting job: "He bares his soul," "He puts it all up on the screen." I've seen a lot of movies but I've never seen anything "put up on the screen" the way Rourke presents his weathered "Ram." His friendly interactions with people around him, the way he kicks off his jeans in the tanning salon, how he hunches over a pay phone: he provides the character a veracity that proves immune to even the most heavy-handed melodrama (as demonstrated in scenes involving Evan Rachel Wood, whose TV-quality acting would ruin any other film.) I was sure this was just going to be another former Hollywood stud doing the small award-baiting movie, but Rourke goes above and beyond, bringing life experience to what could have been marred by falseness (like a badly staged fight.)

The second thing The Wrestler has going for it is that it genuinely cares about wrestling and the men who make it their profession. The matches themselves are tributes to their dedication and showmanship, and the camaraderie amongst fighters who pound each other flat on the canvas makes them even more respectable. These two strengths are tight as ropes, which is good because the movie's got a lot of problems. Besides Wood's obnoxious take on the cliché estranged daughter character, the parallel between Rourke and aged stripper Marisa Tomei selling their bodies is kind of lame, the Jesus imagery is hard to take seriously, and more than a few things that should be implied are flat-out stated by characters (and the director.) I would say that technically the next two or three films on this list are much better, but The Wrestler is unlike anything else I saw this year. Rourke has the tortured body and tired face of a man who has barely survived. Is this movie real?

6. 35 Rhums (35 Shots of Rum). Every new Claire Denis film is a surprise, this one is no exception. A step back from the metaphysical bafflement of The Intruder, 35 Rhumsfollows an Ozu-ish plot about a grown woman living with her father who is unwilling to give up the close relationship she shares with him by moving out and finding a husband. Her father, an aging train conductor, doesn't want to give her up either: she's just one more thing he'll lose before there's nothing left for him. As far as story that's all you've got, but for a filmmaker like Denis who specializes in moments and gestures that's all you need. The scenarios are brilliantly observed and the opposite of force-fed: we learn about how one character feels through their reactions to another, captured even while the people on screen remain oblivious to them.

Whereas Friday Night was about the distance that exists even in connection, 35 Rhums is all about trying to maintain intimacy (and yes the father and daughter have got the kind of closeness that just teeters on pushing past the platonic) to keep from being sucked out into a cold, indifferent world; Denis' patented style of existential detachment works especially well in quiet moments of the two leads holding each other, walking on the beach, sharing dinner, dancing, yet finding confrontation or resolution unbearable. Should that barrier be breached, the entire base of their cherished bond would burst, inevitable given Denis' awareness of how we hurt each other out of stubborn love; how isolated our existences become even when we're close together. Denis regular Alex Descas is haunted and graceful as the windower who brings the train back and forth through the same tunnel day after day, the monotony of his existence slowly devolving into the resignation of old age. What is there after the last shot of rum? As always, beautiful camerawork by Agnès Godard.

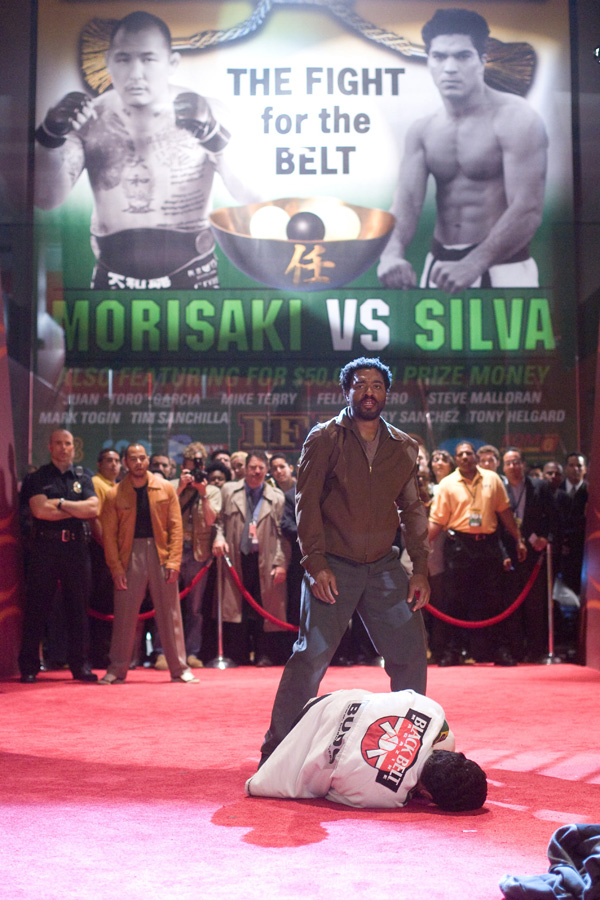

7. Redbelt. Chiwetel Ejiofor is Mike Terry, a martial arts instructor with a unique code of ethics. He's nothing, not even a blip on the screen, especially compared to a big shot fighter who is so famous he's apparently the only person on any TV at any given time. Mike will stick to his guns and his own ideals of honor and preservation even after his values have been compromised, his students disappoint him and his wife betrays him. Mike is an old warrior, and not just in the physical sense: he believes in traditional ideals like truth and unfaltering honor, making him the perfect opponent to the kind of scheming corruption David Mamet uses to paint his seedy worlds.

The criticisms of this film seem to be based on whether or not the world needed a pretentious art-house version of Kickboxer. Even if that doesn't sound as awesome to you as it does to me, if Aronofsky can get away with applying Dardenne-style aesthetics to the world of professional wrestling (and Jean-Claude Van Damme can make his own gloriously pretentious art film*) why should Redbelt be faulted? Personally I couldn't be happier Mamet joined a Brazilian jiu jitsu class and after the second or third lesson decided to make a movie about it! At the very least it gives us something we really needed: Ejiofor in a powerful lead role, and let me emphasize the word powerful. He plays Mike with such hard, resilient presence you believe his level of badassness (or is it badassity?) even without the fights and hardcore training sequences, but there's a vulnerability too that's just as visible. Ejiofor carries the movie, which at some points clearly appreciates the help (I'm still not sure how to feel about the Emily Mortimer/window incident at the beginning, although I dig the fact that it's fucking weird) and at others tightens perfectly around him like a sparring glove (that's, you know, tightened.)

In Mike Terry, Mamet finds his first truly compelling male lead (Spartan's Bobby Scott was close but came up short of the mark), and finally manages to keep his trademark ridiculous plot mechanisms to a minimum (Mike has a cool idea, they steal it: end of con) while maintaining his cynical view of slick conspiratorial institutions and inherent human greed. And instead of being saved at the eleventh hour by undercover Asian US Marshals, Mike Terry – the guy perpetually holding the black marble – stands up against those who would diminish his skills and his honor through sleazy double-dealing.

*Ooh Dardenne and Van Damme, making a movie together – imagine it!

8. Still Walking. Still Walking! My eyes twinkled when I first saw it listed in the TIFF schedule. I speculated what it might be about: memories of Walking Tall and Alex Cox's Walkergot me thinking about a man yeah, a tough motherfucker walking down a street, perhaps with a shotgun at his side! Where's this walker going, and who's going to be seeing the business end of that fowling piece? They may have killed his family they may have gunned him down they may have burned his melons and raped his dog and taken his legs but he's still walking!

Ok just kidding (although I hope I've inspired Chris Funderburg to write another action movie with that description – how about one called Fowling Piece, Funderburg? That's a lost Bronson title if there every was one.) What we've actually got here is something of a quiet masterpiece, with another family gathering, another absent son, another upbeat story about parents and siblings ripping into each other, albeit much more politely than in Christmas Tale (what do you expect, they're Japanese.) Following his excellent Nobody Knows, Hirokazu Kore-Eda sets the table (and only somewhat metaphorically, there's a lot of delicious-looking food served in this movie) with a group of characters who could have easily been clichés: the grumpy judgmental old father, the spazzy self-centered daughter. But Kore-Eda uses their personalities to bring out fifteen years worth of missed opportunities and dredged-up disappointments.

Taking place almost entirely in the house where a family gathers on the anniversary of the eldest son's tragic death by drowning, Still Walking is about the way people live their lives and how life choices come under scrutiny in the fragile family environment. Although that's a particularly brutal subject, Kore-Eda comes at it thoughtfully and never with a heavy hand. While there are few scenes that cause as much wincing as the mother subjecting a young boy semi-responsible for the death of her son to an awkward annual groveling, there are also few as sweet and sincere as the gruff old man bonding with his step-grandson. It's good to see Kore-Eda has gotten over the sentimentality of After Life but is still able to make a film that's as life-affirming as it is tough to watch. This is challenging material which more than any film this year displayed a clarity and understanding of the impact of late-life family gatherings, and of Japanese cinema in general.

9. Me and Orson Welles. Richard Linklater's little movie about the 1937 staging of Mercury Theater's first production (a heavily-edited "Julius Caesar" set in Fascist Italy) is irresistibly charming for both film enthusiasts and anyone interested in a genuinely sweet romance. Which is extremely surprising considering it stars the guy from High School the Musicaland Claire goddamn Danes. I credit Linklater for constructing (on the Isle of Man no less) a pre-war Manhattan that's bristling on the foundation of fantastic newness: an exciting atmosphere of art and inventiveness that makes everything seem romantic. And who better to symbolize said pulsating creativity than a young Orson Welles, still a few years from Kane but already a living legend in the radio and theatre.

At the center of the film is Christian McKay, who plays Welles as nurturing teacher and egomaniacal dictator, as brilliant and debonair as he is intolerably boorish and manipulative. The impersonation of Welles is dead-on, but McKay's characterization goes beyond mere imitation: it's a performance that's more fun to watch than any other this year. The rehearsal scenes detailing his working methods are both fascinating in their examination of a brilliantly insane artistic mind and hilarious in showcasing Welles' demanding and spastic direction of the befuddled cast and stagehands. The movie sets up a great drama in the High School kid's relationship to the director, and entertains equally with a great cast as the Mercury up-and-comers (it shares with Happy-Go-Luckyanother excellent performance by Eddie Marsan, here playing a henpecked John Houseman) and its wealth of Welles trivia, such as the menu of his pre-performance meal (2 steaks, 2 potatoes, a pineapple, triple pistachio ice cream and a bottle of scotch.)

I wish they had come up with a better title, but the playful and unpretentious one they went with perfectly suits Linklater's approach to this material (also Mercury Days or something would sound pretty lame I guess.) He handles the film lightly but with the kind of technical expertise (something else it shares with Happy-Go-Lucky is terrific camerawork by the great Dick Pope) that's been consistent throughout his varied career. His movies may be hit-or-miss, but this one's definitely a hit.

10. The Foot Fist Way. Danny McBride is Dan Simmons, a martial arts instructor with a unique code of ethics. He's nothing, not even a blip on the screen, especially compared to a big shot fighter who is so famous he's apparently the only person on any TV at any given time. Dan will stick to his guns and his own ideals of honor and preservation even after his values have been compromised, his students disappoint him and his wife betrays him.

But besides serving as a comedy version of Redbelt (imagine a Mike Terry-Dan Simmons face-off!), Foot Fist Way manages to distinguish itself from the Will Ferrell category of "pathetic middle-aged man placed hilariously in sports environment where he will be humiliated and probably have at least one scene in his underwear" by maintaining its low-concept comedy basis with humor that's never forced but rather seems almost "found." And is, incidentally, hilarious. McBride, previously known as "that other ugly guy from All the Real Girls," had quite a year, and his biggest accomplishment among amusing turns in Tropic Thunder and The Pineapple Express was somehow shaping Dan Simmons – a horrible bully and self-idolizing maniac – into a likeable character. Was there a sadder image this year than Dan sitting alone outside Chili's after separating from his wife? Even when he's bullying sidekick Julio or knocking defenseless old men to the ground and reveling over his defeated foe as "king of the demo," Simmons is almost oddly relatable (if you don't cheer at the end, this movie didn't work for you.) Director/co-writer Jody Hill (who is also hilarious as Mike McAlister, fifth degree black belt) provides the movie an off-beat rhythm and sense of realism almost as expertly-handled as that of The Wrestler. See The Foot Fist Way if you haven't already, and make sure to check out the DVD's alternative ending on the bleachers outside the gym. Also, everybody's seen the Conan bit right? It's magic of an Andy Kaufman caliber.

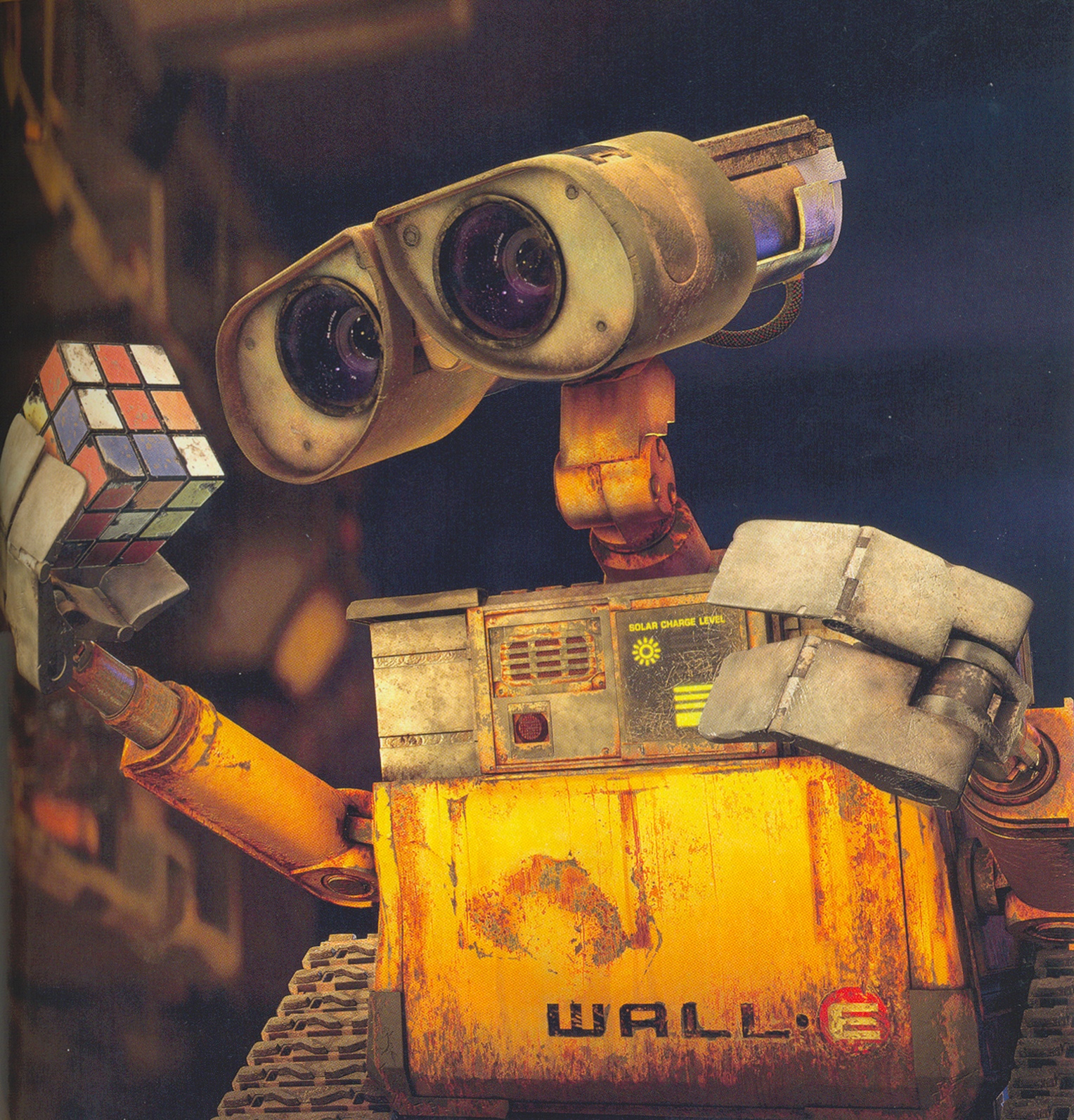

In a league all its own: WALL-E

I hold Pixar to ridiculously high standards: Ratatouille didn't even make my official top ten last year (what the fuck man?) I expect each one to be not only a great animated movie, but a great Pixar movie: that is, exceed the bar that's already placed high in terms of criteria. The first half hour of Wall-Enot only exceeds all expectations, it actually makes the rest of the movie seem disappointing when it resorts to being just an excellent Pixar movie. Not to disparage the scenes on the Axiom, which are phenomenal ("I don't want to survive! I want to live!") or the perfect final scene, but Jesus has there ever been anything as amazing in any film – animation or otherwise – as watching this busy little garbage compactor go about his daily life on a hauntingly desolate Earth? Has anything been more visually compelling than the buildings of stacked waste cubes, the floating grain of dust storms, the shells of depleted robots frozen mid-task among the salvage? Moreso, has any song ever seemed more romantic than when Wall-E plays "It Only Takes a Moment" for Eve?

Besides surpassing the marks that have become reliable Pixar stables (great characters, brilliant computer animation) Wall-E is, on its own time, a wonderful love story: how about the two of them dancing out in space? It's impossible not to point out an amazing aspect of every single sequence, and only the sometimes bogged-down "human" message and loss of Wall-E as a character in the final 20 minutes of the film detract from its bottomless wealth of innovation and craftsmanship.

Worth mentioning: The Bank Job.

To be honest I was ready to give up on this movie after half an hour. Too boring! Too much going on! Why isn't Statham shirtless and greased up and beating up a bunch of punks with a fire hose? This, I thought, is pretty typical of the director of Cocktail, Dante's Peak and the remake of The Getaway. But as the story progressed, and what started as a simple heist ends up involving backstabbing crooks, corrupt cops, MI5, black militants and the Royal family, so did the scale of pure excitement rise considerably. What makes this movie so appealing is the period aspect: none of the thieves wields a laser cutter to split glass cases, there's no slinky chick flexing underneath wires her ass millimeters from tripping the alarm, no clever new way of blowing a safe using water and a balloon and synchronized time locks – it's all old school.

Statham, all brute force in a leather coat, fits in perfectly with his 70s surroundings and has dynamite chemistry with Saffron Burrows as a former fling who comes back to set him up. The aspects of the robbery itself, like the amateur radio operator who picks up the thieves' communication, are the kind of bizarre circumstances that have to be true. I never thought I'd see a movie where the crooks stop in the middle of a bank job to take a nap! Honestly merits a place with some of the best group heist movies: The Asphalt Jungle, The Killing, Rififi, Inside Man. Additionally, it has what is possibly the coolest poster of any movie from the last ten years.

(continues on next page with the Worst of 2008)

<<Previous Page 1 2 3 4 Next Page>>

home about contact us featured writings years in review film productions

All rights reserved The Pink Smoke © 2008