NOT TELLiNG:

MELViLLE AT CHRiSTMAS

~ by john cribbs ~

Jean-Pierre Melville's Deux hommes dans Manhattan, his only movie set entirely in America, and Un flic, his final film, are two very different movies from opposite ends of the director's sadly abbreviated filmography. Although separated by little more than a decade and seven films, the rapid evolution of Melville's career makes it feel as if three times the amount of movies had materialized in between these two. While Flic is steeped in an air of resignation, a logical culmination of the filmmaker's most famous stories of weathered cops, gangsters, Resistance fighters, heisters and hitmen reaching the bloody end of the line, Manhattan taps into an energy completely unlike anything from his other films, even the ones that came before it.

While the languor of finality is embedded in Flic's bluish gray tones, by contrast the vibrant black & white location photography of Manhattan, his fifth film, lends it the unruly excitement of a debut feature. It's mild and rambling and spirited in the same way Flic is complex and precise and fatigued. Its romantic view of nocturnal New York is a direct contrast to Flic's inescapable, coldly sterile daytime Paris. Manhattan ends with hope for its self-hating shutterbug; the characters in Un flic have moved so far beyond hope they wouldn't even recognize the word. Manhattan feels like a beginning, Flic feels like an end.

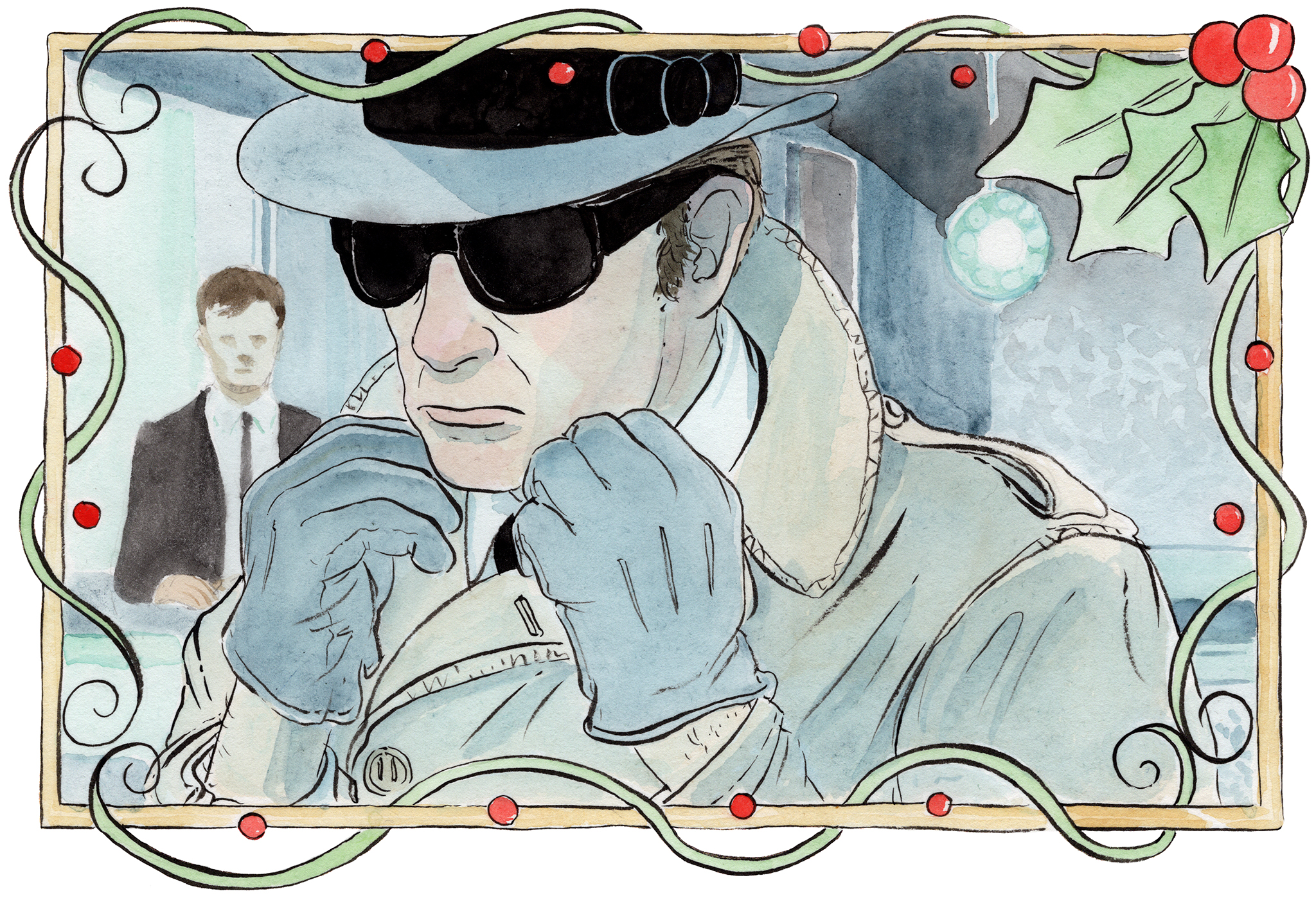

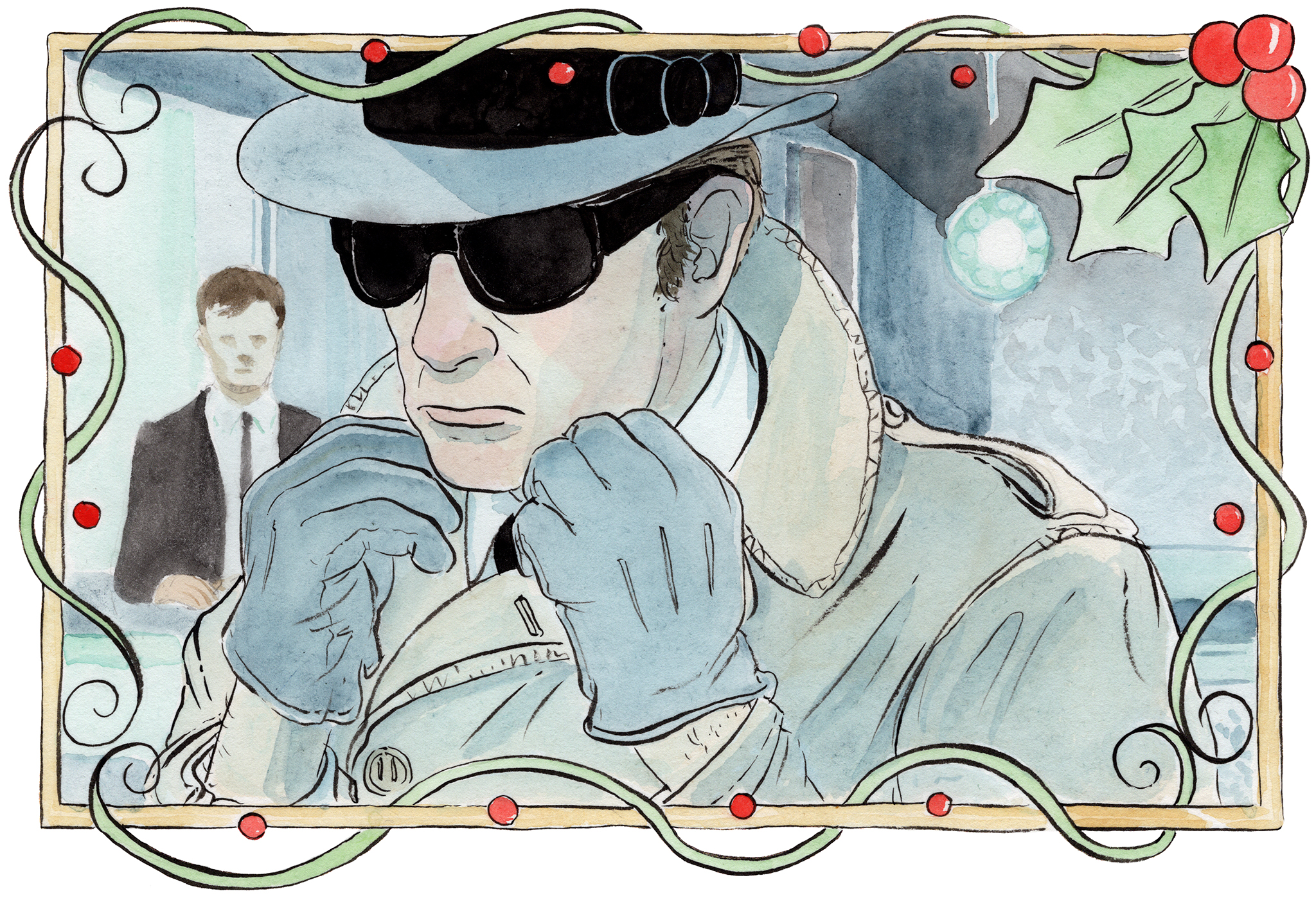

Beyond their stylistic distinctions, the films barely belong in the same genre. Manhattan is about a reporter and his photographer buddy trying to hunt down a missing U.N. delegate over the course of a long New York night, while Flic spans roughly a month and a half chronicling the end of a relationship between an apathetic policeman, his club-owning criminal acquaintance and the gorgeous blonde with whom they're both involved. There's technically no crime perpetated in Manhattan, yet it wears traces of American noir-thrillers, plot elements like moving a dead body and a string of steely femme fatales who know more than they're willing to say. Nobody packs a gun, but a concealed camera with a blinding flashbulb ends up being just as deadly a weapon. A trenchcoat/fedora combo on the lead character wouldn't look out of place among a lineup of the stick-up men and murderers of Melville's more American thriller-inspired films.

Yet Flic, a movie that involves a bank robbery, an assassination, police torture, a love triangle, a flawlessly timed and executed train heist via helicopter and climactic shootout between cop and crook, is a much more subdued affair, juxtaposing its thrills with the kind of heavily quotidian conduct Melville loves so much. Best exemplified in scenes from Le Cercle Rouge where the jewel thief-hounding inspector has to get home and feed his cats, Melvillian moments of the mundane pervade Un flic. Instead of a stream of showgirls shedding layers of clothes in a bustling backstage of Manhattan, we've got Richard Crenna changing into slippers in a bathroom that shifts the tension of the daring 'copter-to-train heist to a leisurely lull.

Rather than our determined heroes meeting one beautiful and mysterious woman after another, Un flic employs a subplot involving an out-of-work banker lying to his wife about going to job interviews when he's really pulling off secret scores.1 While Flic is nothing if not cool and sexy, it's anything but romantic; Manhattan, which lacks a love story or a gorgeous movie star, is infused with romance, its animated scenes of New York nightlife a vivid contrast to the desolate, stormy seaside road on which Un flic opens with its infinite stretch of colorless, vacant condo balconies abandoned by beachgoers for the season, devoid of human activity.

So while it's not exactly surprising that these movies are unalike - one's title is Un flic, the other is a U.N. flick - the most salient detail one notices when putting them next to each other is how their tones seem to have been swapped. The story of a slick, well-dressed nightclub owner pulling off heists under the nose of his cop buddy should be revitalizing rather than resigned. Following a sleepy-eyed journalist and his flask-swigging cameraman companion as they run up against one dead end after another in their search for a stranger they expect to find shacked up with a lady somewhere in the city ought to be taxing, not rousing. Just consider Manhattan's milieu: it really does feel like one long night, for which one of the two men is roused from an alcohol-induced sleep, during which both of them become progressively more tired as the movie goes on.

Yet there's an invigorating sense of discovery with each new development of their investigation, even after it ends over the cold body of their quarry, Mme. Fevre-Berthier, whose reposed corpse they find sitting upright, eyes closed on the couch as if he's just napping. By contrast, Coleman the weary cop examines a corpse early in Un flic: a murdered young woman propped up as if frozen mid-action similar to Manhattan's delegate, but whose expression is one of chilling ambivalence, the victim staring forward with eyes open in a grotesque mimicry of life, seeming to accuse the helpless Coleman despite not really seeing him at all. These are two similarly-posed yet opposedly-situated dead bodies, both discovered in an apartment on the night of December 23rd.

Because what these two films do have in common is that they open on the same date, the late afternoon/evening of December 23rd. Melville, handling narration duties as he did in Bob le Flambeur, notes the setting of Manhattan in the film's very first line: "It was 3:32 pm on December 23 when the old 1912 gaslight, forgotten by urban planners, lit up for the kids on 43rd street." The scene shifts from an Irish, an Italian and a Jewish boy playing in front of the United Nations,2 celebrating NYC's diversity and rustic charm (the gaslight), to tuba players belting out "Silent Night" at a fully-decorated Rockefeller Center covered with holiday pedestrians and a Salvation Army Santa.

Un flic also shifts focus from a small group of people, four gangsters knocking off a bank at closing time on the outskirts of Paris (on what is later revealed to be December 23rd), to heavy traffic in one of the most recognizable parts of the city, again with street lights igniting to illuminate Avenue des Champs-Élysées where Alain Delon's Detective Coleman begins his shift. Once night has fallen and Coleman has started to look into the planned drug deal that will involve the men from the opening robbery, we hear that same generic tuba rendition of "Silent Night" used in Manhattan as he turns onto the only street in the movie where Christmas seems to exist. Strewn with lights, cluttered with cars, busy with shuffling bodies, Coleman arrives at this festive set with only business on his mind: getting some info from an informant, his own Salvation Army Santa. That's right, big red works for Coleman - and considering there's only one day until Christmas you would assume the guy's got more important things to do!

As soon as Coleman turns the corner, the brass instruments and cheerful crowd noise becomes a whimper in the distance and we're right back into the unadorned streets. Similarly, the holiday fades as the two men in Manhattan visit increasingly isolated interiors (from a live theatrical play, a recording session and a burlesque club to a private brothel, a hospital room with a sole occupant and an apartment with a dead man). So why this specific date of the 23rd leading into Christmas Eve? Nobody in these movies says "Merry Christmas." The season presumably had little sentimental value for the Jewish Melville. It could have something to do with the French Resistance, subject of a major subplot in Manhattan and dealt with more fully in the director's Army of Shadows, scoring one of its most significant strikes when Vichy deputy leader Admiral Francois Darlan was assassinated by Resistance fighter Fernand Bonnier de La Chapelle on December 24, 1942.3 Manhattan's former Resistance fighter suffers a less heroic coronary death.

A slightly more plausible explanation: on the day after the December 23rd robbery of Un flic, Richard Crenna's bank robber Simon organizes a post-heist meeting with his associates at the Musée d’Orsay. During the visit, Simon first considers Van Gogh's "Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear and Pipe," a painting memorializing the artist's mutilation of his ear on the night of December 23, 1888, the severed lobe of which having possibly been gifted to a whore named Rachel the next day, a thoughtful yet gruesome Christmas gift.4 After speaking with his crew, Simon closely studies another Van Gogh, "Self-Portrait with Grey Felt Hat."

Even though this painting pre-dated the artist's night with the open razor by a year, its placement in the scene makes for a fascinating comparison to "Bandaged" as it profiles the opposite side of his face (the non-mutilated ear). The order of these painting's appearances, "Bandaged" followed by "Grey Felt Hat," suggests the more presentable, less-mutilated Van Gogh portrait in a grey hat, not unlike the one Simon is wearing, to be a cover-up of the previous representation. The artist as disheveled, mentally-unbalanced self-mutilator vs. the artist as dapper, healthy-if-somewhat orangey gentleman, the severed ear hidden from view. Simon the desperate, unfeeling bank robber vs. Simon the harmless, posh chap enjoying an afternoon at the museum. (It's notable that in the reverse shot, Simon's right ear is exposed - together with the painting, they make a complete man/face.)

So we have two portraits of Van Gogh, months apart: in one the result of his madness is evident, in another it isn't - the contrast of these two portraits of the same man are not a lie, individually they're just not telling the whole story. For what is Christmas if not putting a pretty gloss on everything, covering it to make it attractive, more acceptable? Bright lights and tinsel on a dead tree. In Manhattan, a reporter for the French Press Agency named Moreau, a noted "night owl" played by Melville himself, is tasked with locating a missing diplomat, then covering up the scandalous truth about the circumstances of his death at the apartment of his mistress. In Un flic, Coleman knows that his pal Simon is involved in shady enterprises but prefers to saunter into Simon's club, tickle his ivories, share his girlfriend and act like everything's fine.

While Moreau's covering of the truth is noble (he wants to spare the diplomat's family embarrassment and maintain the reputation of a beloved resistance fighter), Coleman's is entirely selfish: Melville shows his relationship with Simon to be the only thing he has outside of the tedious, soul-crushing duty of investigating urban night crimes. Even after he's positively identified Simon as the mastermind behind a bank and drug heist, Coleman hesitates to move in for the arrest that will effectively end the friendship. This gets at the core of the difference between these two films: in Manhattan, the ultimate decision is that the truth remain covered. In Un flic, it must inevitably be revealed. Melville suggests that acknowledging the truth ruins Coleman, but it's in supporting the lie that Manhattan's ostensible villain finds redemption.

It all comes back to the cryptic, cribbed Celine quote from the opening of 1962's Le Doulos: "Mourir...ou mentir? To lie, or to die?" For most of that film, we're led to believe that Silien is a police informer whose actions are against his criminal comrade Faugel; once Silien has revealed his true intentions to protect Faugel, both men are fated to fall. Melville explored this idea further in Le deuxième souffle, wherein the final act the great Gu Minda is more than willing to sacrifice himself to expose the police-generated lie that he's a dirty rat who betrayed his fellow crooks. The idea is perfectly illustrated when Minda is driving with Commissioner Fardiano handcuffed in the back seat, laying out all the details of the recent roadside robbery as Fardiano begs him to stop, knowing that the only reason he's hearing the truth is that he's about to be shot. Melville suggests that once the lie is gone, the only thing to do is to die. He plants the idea that his characters are aware of this early in Un flic, following the scene of Simon considering the self portrait of Van Gogh (a famous suicide) with Coleman practicing the rapid fire shooting he'll put to use when Simon performs his suicide-by-cop at the end of the film.

It's a death that births the lie in Manhattan, when Moreau and his photographer partner, the Scotch-loving Pierre Delmas (Pierre Grasset), hit a light switch in the apartment of an American actress to reveal the body of Fevre-Berthier. As Moreau phones in to his editor only to be connected to his paper's director, the opportunistic Delmas drags the body to the bed and lays it next to a picture of the actress to create a more scandalous portrait: Delmas doesn't want "Van Gogh, gentleman with a hat," he wants "Van Gogh with a bandage over the ear he cut off to gift to a hooker." After Moreau fails to talk Delmas out of his scheme, the director arrives, appraises the situation, and tries to convince Delmas to surrender the film in his camera: "There is more to journalism than such traditions. Reporting is not just saying and showing everything. Not telling, sometimes, might be more honest."

The irony is that Delmas hasn't created a lie, merely an exaggeration. Moreau and the director's plan to physically move the body to another location is the lie which Delmas now threatens, although the director has smoothly side-stepped what they're conspiring to do by suggesting they're simply "not telling." His commitment to deceit comes from a good place, specifically the preservation of Fevre-Berthier - who has been said to be of pre-war vintage, "when statesmen forgot they were politicians" - as an idea, a legacy. "It's only when such men are gone that wars break out," Moreau's editor related, and Moreau's director seems convinced that revealing the truth will create another kind of war, one forged in the press which will tarnish the heroism of French WWII fighters. As he'd make clear later in Army of Shadows, Melville considers the code of ethics of his gangs of heisters to be on par with that of his gang of resistance fighters. The morality of the two factions isn't the same, but when it comes to loyalty within the group, telling is the most unforgivable of transgressions.

Like Moreau's director, the characters of Un flic are able to live with a lie by simply not telling. The first time Coleman enters Simon's club, the mutual friendship between the two men and Catherine Deneuve's femme chic Cathy is established without dialogue, through looks from one character to another. The wordless exchange of the threesome is repeated in Coleman's next visit, during which he couldn't look more content to be in the company of Simon and Cathy, but his final appearance at the club is nothing but words as Coleman recites the names of Simon's accomplices for the criminal to unconvincingly deny one after the other. Coleman's interrogation is really a warning to Simon (he's already gotten henchman Louis to break his silence) but it effectively collapses the facade and one of the men now has to die.

The Coleman-Simon dynamic is a departure from most Melville movies where the crooks clam up and the cop won't stop talking. Coleman more closely resembles Delon's stoic assassin Jef Costello from Le Samourai, getting down to business as quickly as possible and more comfortable not saying anything, neither confirming or denying his secret life as a hitman. The standard motivation of Melville's lawmen is to trip up their antagonist by getting him to talk, to "tell" all over the place, to manipulate the truth in service of a lie, to take everything that is Gu Minda away by claiming that he squealed. Emphasizing the eloquence of silence is hardly surprising coming from a man whose first film was all about silence: it's all the French guy and his niece of Le Silence de la mer can do to maintain a pretense of normalcy to sit there and not talk while the German lieutenant occupying their house (like the later chief policemen of Bob le flambeur, Les Doulos and Le deuxième souffle) chatters endlessly. But Melville's characters would only get more quiet further down his career, the 27-minute silence during the heist of his penultimate film Le Cercle Rouge (replicated in Un flic's two big heist scenes) signifying the pinnacle of his tragic anti-heroes' reticence.

"A man in front of a mirror means a stocktaking, a summing-up," Melville once stated. Sure enough the man loves a good moment of quiet reflective stocktaking, as seen in Bob, Le doulos, Leon Morin and Cercle Rouge, but another stylistic evolution that reached its peak in Un flic are his use of reverse close-ups in which one character studies another. I've already brought up the two most significant, Coleman looking into the vacant eyes of the dead prostitute and Simon gazing at the grey-hatted Van Gogh: someone who is alive looking at someone who is dead but petrified in a posture of life.

These two sets of champ-contrechamp mirror each other, but Coleman's commiseration for the blonde victim in front of him is more elusive. Is she an embodiment of the "indifference and derision" Coleman-by-way-of-Vidocq claims mankind inspires in policemen? Or the futility of his role as a law officer? Or is this another of Melville's narrative divinations, predicting where Coleman will end up with the women in his life? Coleman shares similar reverse shots with the film's two other blonde female figures, Cathy and Gaby, a transgender street walker who serves as his informant. Coleman's relationship with Gaby is another lie, not of Gaby's gender but Coleman's tolerance towards her lifestyle. He treats her with kindness until after he believes that she's fed him misinformation about the drug deal on the train, at which point he resorts to beating and humiliating her at the police station, referring to her as "he/him" and suggesting she "wear men's clothes" while promising to teach her what it is to be a "squealer." The typically apathetic Coleman has reverted to one of Melville's poisonous non-stop talkers, "truth" pouring from his mouth as he physically and verbally assaults Gaby, even though the only thing being truly revealed is his own cruelty and intolerance. He demands she be thrown out of the station, as dead to him as the ashen blonde murder victim. It's February 8th at this point: Christmas is long over, and so is the pretense of Coleman's goodwill.

The next morning Coleman pulls his gun and shoots an unarmed Simon, fulfilling the prophecy of the previous scenes. His last human contact in the film is with Cathy from across the street, frozen like a cold, dead portrait. Earlier Cathy is surprised when Coleman tells her that Simon knows about their affair and has known all along, having never guessed that both men are content to allow it to happen by simply not acknowledging it, aware that it's the only way it can continue without repercussions. These two men have also tried to maintain their friendship by letting their respective roles as determined commissaire and prolific career criminal carry on without comment.

The artificiality of the love affair between Coleman and Cathy already feels oddly lifeless, even for the famously love-shy Melville: we're talking about Alain Delon and Catherine Deneuve, two of the most gorgeous figures ever put on screen (and a real-life couple to boot) yet their rendezvous, initiated by a bit of play-acting with Cathy "surrendering" to Coleman's cop, is drained of intimacy - again, the movie has no use for romance. And now that Coleman and Simon's opposition has been brought to confrontation, even the artificial affair between Coleman and Cathy can no longer exist for the same reason that the men's facsimile of a friendship has evaporated (even though it would logically be easier for it to continue without Simon!)

Though it pains him to unmask the lie and sever this relationship, at the end of the day (although it's actually the start of his day) Coleman is a cop, and he can't let a crime go unpunished. The demand of Coleman's position results in everything in his personal life - the comfortable companionship of a criminal, a robotic love affair with Cathy, unguarded tenderness with an attractive informant - being based on a falsehood that the truth will inevitably topple. He's a cop and it's his very nature, his incessant need, to seek the truth, even to his own detriment.

Delmas fills the duty of the Melville cop in Two Men in Manhattan, in that he won't let Moreau and his director get away with the crime of restaging a death scene. His intention to publish the photographs he took of Fevre-Berthier isn't unlike the asshole commissioner's framing of poor Gu Minda: he wants to tell the truth, by deploying a different lie. Delmas even gets to play bad cop by roughing up the hospitalized American actress into revealing the whereabouts of her dead lover, in a scene as cruel and invasive as Coleman's humiliation of Gaby. Delmas is openly abusive towards most of the women he and Moreau come upon in the film, his misogyny communicated through the camera that makes him "feel like a man" which he uses to snap non-consensual nude pictures of a showgirl as she changes and intends to use to capture the reaction of Fevre-Berthier's widow at the moment she's informed of his death. Like Melville's cops Delmas has a zest for his work - rather than find it stifling like Coleman, he allows his nocturnal gig to define him confiding in Moreau "I hate to feel alone," that he only feels complete with the requisite tools of the nighttime city tabloid photographer, a drink and his camera: "Take them away and it's only me."

It's enough for Delmas to be who he is, not only emotionally but ethically as well. Connection to people just means more artificiality, a greater need to build up relationships based on lies. It's no wonder he displays immediate contempt for Fevre-Berthier, a man everybody around town seems to know and like, whose sudden death now necessitates that others protect the fabrications which the diplomat has constructed. Like Coleman, Fevre-Berthier has an affair (multiple affairs) going which even his adult daughter Anne knows about but keeps under wraps. Although Fevre-Berthier is never present as a living character, Delmas' attitude towards him seems to be pretty close to that of Michel's towards Ferchaux in Melville's other American-set movie Magnet of Doom. Delmas and Michel are peas in a pod - dirt poor, self-serving, irreverent, abandoning a woman to go off on a mission. They are both unimportant side characters who want to wrestle a bigger fish's story away from him. Michel resents Ferchaux, the disgraced banker who hires him as his personal secretary as he flees to the states to avoid French authorities, at first feeling inferior to a reputedly rich and important man and finally fed up as Ferchaux attempts to maintain his stature despite being ruined and broken.

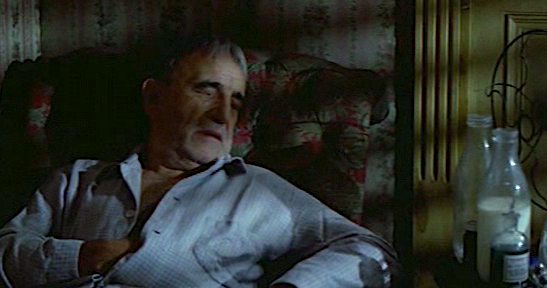

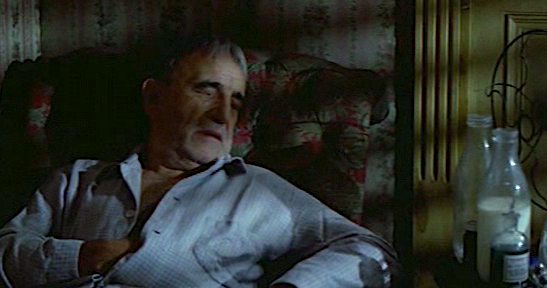

Ferchaux is someone whose pretense of power and authority Michel sees through, and he becomes progressively more pitiful to Michel. When the two end up trapped in a dilapidated colonial home in Louisiana, Ferchaux desperately tries to appeal to his companion not as a hot shot businessman but as an old man who's dying. Needless to say his efforts are in vain and become increasingly pathetic, Ferchaux going so far as to situate himself in a chair hand over his heart waiting for Michel to return and react to his "death." This is the exact position in which Moreau and Delmas discover Fevre-Berthier; as a mockery to the man whose stature Delmas holds in no respect, the photographer contrives a travesty of the same posture, much to the horror of Moreau (Pierre Grasset would play a character who really does die sitting up in Le deuxième souffle). It's doubly indicative to find Delmas in his imitative parody of a revered Resistance fighter's death that he was introduced to the audience in his own apartment, shirtless in bed with an arm draped down in emulation of the Death of Marat, another martyred hero of French rebellion. The cynical shutterbug sees himself as just and heroic, the subject of his night-long search as a hypocrite and a fraud.

Ferchaux hires Michel to escort him across the ocean with the idea that he's running away and collecting his hidden accounts in America to start a new life there, but really his own lie has been exposed and he's going there to die. He's doomed the minute Michel is hip to the lie, although he mistakenly thinks that perpetuating the myth of his importance to Michel will prolong his sad end. Like many situations in Melville movies, the enlistment of other people only further complicates things and brings about the downfall all the quicker. Recruiting Delmas for the search mission complicates the situation immensely for Moreau, and makes it harder to maintain the lie that he's ultimately tasked to cover up. Melville is fascinated by this individual vs group polarity. Jef Costello, a lone wolf killer, finds his own path to destruction only after connecting with another human being, suggesting he would have been better off alone. Alternately, the squad of Army of Shadows are there to help each other out, but they're all fated to go down together.

Simon's gang in Un flic are destined is its own argument for the failure of groups, even borrowing a little fake ambulance routine from the Shadows team by disguising themselves as medical staff when one of their number is trapped: both rescues prove unsuccessful. Victorious as ever is the solo Gu Minda, who manages to escape police custody in a hospital room without any help. Like Simon and his squad, the Manhattan duo are also stopped by a nurse when they try to con their way into a hospital to interview the failed-suicide American actress, but like Cathy succeed by factioning off the group and gaining access to the patient independently. (One of Flic's best moments is when the hospitalized crook regains consciousness in time to see Cathy, a blonde angel, hovering over him just as she administers the fatal dose into his IV, a reverse of the Manhattan scenario with the long-haired beauty in bed at the mercy of Delmas.)

When the train heist is being planned, Cathy asks Simon, "Only you three know about it?" to which he responds, "No! Only us four." Simon definitely feels there's safety in numbers and a benefit to counting on others to make both right and wrong decisions, but of course one of these trusted four will tell Coleman everything and implicate Simon. I made a stupid joke earlier about how these two films' titles divide them, but really they connect them: a movie about one cop, a movie about two men.5 These solitary characters steal the spotlight from the kind of characters Melville is usually more interested in (a gang of crooks and an admired French spy), and it's the seclusion of these night owls from the bigger world that gives them control of how a part of it is perceived. Bit players like Moreau and Delmas are able to step in at an opportune time. Coleman can either rub elbows with a nightclub owner or take him down as a nefarious thief and murderer. Loneliness is a necessity. These characters are the ones removed from the secret, hard-working bachelors spending the holidays alone because while they may be attached to a larger group, they stand outside the circle. The circle is doomed to splinter apart because someone will tell. Someone always does.

"Declarations of love are written at night," Melville said of Bob le flambeur and its depiction of the all-hours nightclubs, restaurants, dance halls, gambling dens and casinos of Paris, and night is the time for the reclusive. But the population of Un flic's Paris (note: not a declaration of love for the city) are more like those who crawl out from under something to emerge at night, who share a disdain for the sunless blue hungover sky of the movie's awful daylight hours, the darkness their only refuge. Manhattan celebrates the beautiful sleaze and vice of New York, the city's diversity, its danger, every occupant's daily (or nightly) search for where they belong among its back alleys, private clubs, tiny apartments, empty diners and brothels catering specifically to Frenchmen - even the despondent seem to at least be having fun.

Like Bob le flambeur it celebrates the unseen, the underground beneath the flashing lights of the city's gaudy marquees. The world of Manhattan seems so much bigger than Un flic, even though it takes place in a shorter amount of time. Moreau and Delmas always end up in a place where it looks fun or at least comfortable to be (an apartment with a skyline and view of the whole city!), as opposed to Simon's gang who like the thieves of Le Doulos and Le deuxième souffle and the resistance fighters of Army of Shadows, are forced to meet in abandoned houses that are falling apart. "You can judge a civilization by the quality of its prostitution," Melville-as-Moreau says, and a by-appointment-only bordello that "looks like France" is certainly more enticing than a ratty penthouse with a dead hooker and a list of possible suspects written on its walls.

As morning rises on the final scene of Deux hommes dans Manhattan, Moreau finds the fugitive Delmas holed up at the Pike Slip Inn, slumped over the bar as a band plays for no one. Moreau accuses him of selling the staged photographs of Fevre-Berthier and decks him. At literally his lowest point, the photographer glances up just in time to share his own reverse shot with Anne, the delegate's daughter. The moment unexpectedly affects him, and Delmas emerges from a seedy interior that never sleeps into the morning of the city, much like Bob Montagne, to an unexpectedly optimistic future. He ditches his undeveloped film in the sewer and walks beneath the Manhattan Bridge laughing to himself (away from camera, just like the end of another great Christmas-set French film).

No such happy ending for Coleman. Although the final image of the film (the final image of all Melville's films) is Coleman facing camera, he's directionless, driving away from the Arc de Triomphe after shooting Simon. (Similarly, Army of Shadows opens in the Champs-Élysées and ends with a broken man who's just killed his friend driving away in a car to an uncertain destination, waved away from the Arc de Triomphe by a German traffic controller.) Coleman doesn't know how to deal with his loneliness, whereas Delmas is quite literally walking away from his trashed film and his bar haven, abandoning the two things that kept him from feeling alone. The tinge of finality is assuring in Manhattan - Delmas has a new year year to look forward to - but stuck in February, Coleman has a long and empty expanse of days, weeks and months in front of him.

Maybe Melville is suggesting that it's better to leave his characters in dark December when they can see the end of a year coming than languishing in a poorly-defined moment on the calendar with nothing to look forward to. Just look at Gu Minda in Le deuxième souffle, enjoying a quiet "Christmas" with his companion Manouche, set in a cold, empty house with one area nicely decked out with a tinseled Christmas tree and the fire going; like Deux hommes dans Manhattan and Un flic it's specifically not Christmas (identified onscreen as "night of December 27-28"), but rather the end of the year as things are wrapping up and a new life is on the horizon. You won't find a more content Melville anti-hero than Gu alone on New Year's with the Christmas tree discarded in the corner, tearing off the final page of the calendar to reveal nothing of the anguish he'll suffer in the coming months when he goes down like Simon, just alone but not lonely, in a room, not saying anything.

~ DECEMBER 20, 2020 ~

1 Almost certainly inspired by Louis Calhern fussing over his bed-ridden wife while keeping her in the dark regarding his criminal and extramarital activities in The Asphalt Jungle. Both characters end up turning the gun on himself when cornered by the law.

2 It's hard to access, but there's something childlike about several of Melville's films, even though children as characters are non-existent (the one exception being Barny's daughter in Leon Morin). His heroes - cops, crooks and reporters alike - are not family men; most are bachelors and the few older married men (like Melville) have no enfants, terrible or otherwise. Maybe it's the attributes of these grown men - sulking, bullying, often desperate - that make them seem a little like kids who are playing too rough.

3 Bonnier was arrested at the scene and executed by firing squad two days later. Almost exactly three years after the killing, Christmas 1945, Bonnier was rehabilitated by a Chamber judgment revision of the Court of Appeals on Algiers, which ruled that the assassination had been "in the interest of the liberation of France."

4 Van Gogh's self-mutilation happened while he was living at the "Yellow House" in Arles, France with Paul Gauguin. Gauguin, a Delmas-level debaucher, reported the matter to the cops and then immediately fled to Paris.

5 I hate the American title Dirty Money, which means nothing and was presumably only attached to the film because "A Cop" makes for a boring English translation. Nobody in Un flic accepts a bribe of any kind, the heisted loot is only "dirty" because they bury it under dirt. Goddamn it's dumb and I hate it.