BETTER THAN

HiTCHCOCK

c.a. funderburg

It’s the sinister little secret of The Pink Smoke that we don’t much care for Alfred “Topaz” Hitchcock. And while we certainly have zilch-o interest in debating the merits of a filmmaker that everyone can agree is “the greatest of all-time and you’d have to be some sort of malcontented and willful iconoclast to disagree,” we are interested in a strange phenomenon: while we don’t adore the man himself, we have a tendency to love Hitchcock knock-offs.

From William Castle’s lazy copy-catting to Francois Truffaut’s loving pastiches, there’s a chance that if a film shamelessly apes the master of suspense, we’re really going to enjoy it. Brian DePalma, Jonathan Demme, Stanely Donen; the list of great filmmakers who tried their hand at a Hitchcockian shtick is extensive and hugely appealing to explore – and honestly, we’ll take either “French Hitchcock” over the real thing any day, whether you consider the mantle to rightfully belong to H.G. Clouzot or Claude Chabrol.

In this series, we’ll look at parodies, assiduous imitators, and off-brand “Hitchcock-like Film Product” in order to dig into just what it is that we love so much about these movies. Sure, you’ll blanche at the suggestion,* but we think these films are Better Than Hitchcock.

THE BRiDE WORE BLACK

françois truffaut, 1968.

"I suppose an apparition doesn't eat, drink or smoke?"

If you’re going to do a whole series about Hitchcock rip-offs, you better be able to describe just what it is that makes something Hitchcockian, but honestly I’m not the best person to ask. My colleague Marcus Pinn likes to joke that if a critic is quoted in a trailer calling something “Hitchcockian” that quote will always play over a shot of a doorknob turning very. slowly.

Well, there are no shots of doorknobs turning very slowly in Francois Truffaut’s 1968 revenge thriller and I’m not precisely sure what even makes The Bride Wore Black a Hitchcock pastiche other than Truffaut was the Master of Suspense’s most famous acolyte (his 1966 collection of interviews with Hitch, Hitchcock/Truffaut remains the definitive word on the subject of suspense cinema) and the film always gets called a Hitchcock pastiche (even by Truffaut) so who am I to disagree? But I think that understanding The Bride Wore Black in terms of how it fails or succeeds in being "Hitchcockian" is the only avenue I have for understanding what this alluringly opaque film actually is.

So what's the story? If I had to characterize the singularity of Hitchcock’s work, it wouldn’t be the plots that occur to me. Plenty of filmmakers have covered spy games organized around secrets and plans and secret plans transported covertly, constantly in danger of falling into the wrong hands. Plenty of filmmakers have covered strange disappearances (and attendant sinister re-appearances.) Plenty of filmmakers have had psychos lunge out of the darkness at the moment you’d least expect it or their main character fall under the spell of a mysterious and alluring beauty. Hitchcock didn’t invent milking the suspicion that a family member or a lover or a neighbor was secretly a nefarious villain. He didn’t invent “the British style” of suspense films, the one mixing tense thrills with dry humor. He didn’t invent the wrong man wrongfully accused or the average schmo suddenly caught in a web of intrigue beyond their comprehension.

There’s no plot Hitchcock invented, no narrative framework he engineered from scratch. That’s what makes him a genre filmmaker: he built artworks on pre-existing templates.

When I think of Hitchcock and what is most pungent about his flavor, what is the distinct Hitchockian aroma, it’s his curdled view of sexual relationships. Ah shit, that’s being too kind - if Hitchcock has an authorial signature, it’s this: a big fat loser’s enthusiasm for “justified” violence against women. In the early British films, when he’s a journeyman, it’s kept almost entirely in check. The longer his career goes on and the more autonomy he gets over his artistic choices, the more unbridled and grotesque it becomes until at the tail of his career you end up with films like Frenzy and Marnie which are startlingly acrid expressions of “these fucking bitches” covered up by a few unconvincing chuckles and a few interesting aesthetic configurations.*

But no shit, Truffaut’s literally the man who loved women - he doesn’t have that in him! He's not going to make a film fueled (even obliquely) by sexual hatred of the fairer sex. If anything, he’s apt to fall into bouts of womanizer’s self-pity where there’s no punishment severe enough for his narcissistic and never-ending pursuit of any and all women.** Right away you can see that The Bride Wore Black’s basic concept would be alien to Hitchcock: the righteous fury of a wronged woman, a compulsion for revenge. The story of a broken heart, a rent heart; a real woman.

Virtually every component of the simple story I’ve just described is unthinkable in a Hitchcock film. Truffaut compulsively explored the basic idea.

When I think of the description of Jeanne Moreau’s character in Jules and Jim, so specific and essential to Truffaut’s worldview, it’s impossible to imagine the sentiment fitting anywhere in any Hitchcock film: “Let me be frank. She’s not especially beautiful or intelligent or sincere… but she is a real woman.” Just imagine describing Grace Kelly in Rear Window or Ingrid Bergman in Notorious like that. Hitchcock has his girls on the verge of womanhood (Shadow of Doubt, Suspicion, Rebecca – most of these naïfs are especially sincere to boot), his fake women (Vertigo, Psycho & Marnie as well the coded, homophobic revulsion of "not-men" in Strangers on a Train & Rope) and his especially beautiful ones (North by Northwest, The Birds, Spellbound, To Catch a Thief, Dial “M” for Murder) – but a real woman like Moreau in Jules and Jim? You’re more likely to find an honest insurance salesman in a David Mamet film.

Style-wise, there’s something unique about Hitchcock beyond his peerless eye for composition and breath-taking precision with editing and montage. He’s a puppet-master who loves to draw attention to the strings. Part of the show, as he performs his magic trick, is to make you cognizant that a magic trick was done, to increase your awe by pointing out the scope and delicateness and unexpected twists of it all – saying “watch as I astound and confound you, dear audience” is part of the trick itself. He’s among the most ostentatious stylists in cinema.

That’s what makes him so appealing to a filmmaker with a theorist’s mindset, filmmakers like the five Cahiers du Cinema critics turned Nouvelle Vague Filmmaking Superstars who counted Truffaut amongst their lot. The mechanics of Hitchcock’s film are constantly on display – if you’re trying to understand how le cinema itself works, how it functions in generating its effect on an audience, what better films to examine in detail than films that insist on making a show of their moving parts?

It’s easy enough to forget now, but it was the Cahiers critics (Truffaut, Rohmer and Chabrol in particular) who made Hitchcock’s reputation. Before they singled him out as one of their iconoclastic reclamation projects, there wasn’t anything like a consensus that he was one of the greatest directors around. He wasn’t William Wyler racking up Oscars (3 wins for Best director and a dozen nominations) and definitely not an internationally respected artiste a la Jean Renoir, but a veteran genre toiler; one with a brand built in part around his outsized showmanship. Before the Cahiers critics got ahold of his reputation, he was mainly just thought of as a guy who made enjoyably disposable (peh!) entertainments.

That is not to say he wasn’t A-list (whatever that means, you can argue that with someone else) – his first American film, Rebecca, had won an Oscar for Best Picture after all and the man himself was nomiated for Best Director (one of his 5 nominations.)*** But that’s as much a testament to producer David O. Selznick’s involvement as Hitchcock’s – in fact, Selznick and Hitchcock clashed throughout the filming, Selznick eventually overseeing extensive reshoots without Hitchcock’s interference. Sure, it seems oh-so-craaaaazzzzy now that Hitch never won an Oscar for Best Director, but in the mid-40’s it would’ve seemed just as crazy to suggest that he was likely the greatest filmmaker in the world.

The Cahiers critics changed all that with Truffaut leading the charge. One of the key tenants of the auteur theory popularized by Truffaut was that certain directors had an authorial voice that could be heard in all their work, meddling producers and extensive reshoots be damned. Truffaut was insistently contrarian and iconoclastic in his advocacy for Hitchcock as an auteur, vociferously championing even poorly-received mediocrities like The Wrong Man.

In terms of the basic categories from which the French critics picked their favorites to advocate for, Hitchcock wasn't some maligned outsider in need of a champion (like Edward G. Ulmer) or a overlooked journeyman (like Howard Hawks) or a talent who had burned all his bridges with the establishment (like Orson Welles or Sascha Guitry) - if I had to identify the main effect that the Cahiers critics had on his reputation, it would be in their successfully arguing that even his bad films were good.

It’s tempting to point to the Cahiers critics’ influence when Hitchcock’s late-career run of his most esteemed works (Vertigo, North by Northwest, Psycho) coincided with the prominent critics’ passionate support – likely their vocal and frequently contrarian advocacy was just one element in a confluence of successes for Hitchcock. There’s no denying, however, that their writing was massively influential in terms of how Hitchcock is remembered to this day – compare his modern reputation to a somewhat comparably talented and successful director like Anatole Litvak, who Truffaut made a hobby of kicking the shit out of.

The importance and depth the Hitchcock/Truffaut connection is undeniable, of course, I don’t need to make that case. (So why am I?) But I think the connection between their styles as filmmakers is much more tenuous. Hitchcock, of course, had a style that he rarely deviated from throughout his career – his consistency made him ripe for expounding the auteur theory. Truffaut, surprisingly for how strong his authorial voice was right from Les Mistons, continuously struggled to find a narrative instrument harmonious with that voice.

Hitchcock, whose voice it is impossible to imagine outside of his chosen genre, contrasts with Truffaut, who could never find quite the right genre to express himself within. His pair of “Hitchcockian thrillers” Mississippi Mermaid and The Bride Wore Black both came in the first half of his career, when he was compulsively trying on genres and styles (film noir, literary adaptation, melodrama), perpetually dissatisfied with how they fit on him.

He was a filmmaker who naturally struck an elegiac, retrospective pose, returning over and over to the scene of his first success with the Antoine Doinel series, making historical dramas like Adele H. or The Wild Child, coming back to Jules and Jim novelist Henri-Pierre Roche with Two English Girls, even directing himself as the lead in a film (The Green Room) about a newspaper writer who is “a virtuoso of the obituary” (a description which would have fit Truffaut himself at Cahiers.) The Bride Wore Black feels like he’s harking back to his crucial, creatively formative relationship with Hitchcock - and then almost immediately, he’s already reviewing with a pained nostalgia his poorly received (but financially successful) attempt to imitate the master of suspense: 1969’s Hitchcock pastiche Mississippi Mermaid reflects on 1968’s The Bride Wore Black.

But what’s the Hitchcock connection, really? What makes Bride a pastiche, really? Is there a stylistic/cinematic connection or is the Hitchcock element only another example of Truffaut looking back on himself, “Hitchcock” only meaningful as an aspect of his defining work as a critic, Hitchcock/Truffaut? It’s interesting to me that Truffaut considered Bride one of his weakest efforts and seemed to want to disown it almost immediately – what had inspired him to make it in the first place? Did he really want to try out a Hitchcock impression, only to find it was a bad look on him? If so, why did he return almost immediately with the equally Hitchcockian Mississippi Mermaid? Or is their equal amount of Hitchcockiness actually “almost none?”

The connections seem to be there. A key but superficial link between Bride and Hitchcock is that Truffaut’s film was scored by none other the composer Bernard Hermann, perhaps the artistic figure most associated with the man himself. If you can’t instantly summon into your head Hermann’s scores for Psycho and Vertigo, you probably don’t care much about the sacred art of le cinema and Hermann’s collaboration with Truffaut was one of only two times he worked with any of the Cahiers critics despite their veneration of his work (the other time being on Truffaut’s Fahrenheit 451 adaptation.)

But what makes the connection superficial is that Hermann was around forever and wrote music for everything from Taxi Driver to Jason and the Argonauts – and while Martin Scorsese and Ray Harryhausen no doubt admired Hitchcock’s work, you’d be hard pressed to described either of those films (or Hermann’s scores for them) as Hitchcockian. The fact is that Hermann’s Bride music doesn’t directly ape his Hitchcock themes; it’s a moody orchestral score like he did for films and tv shows from It's Alive to Have Gun, Will Travel. The presence of Hermann’s work is a strangely empty signifier.** **

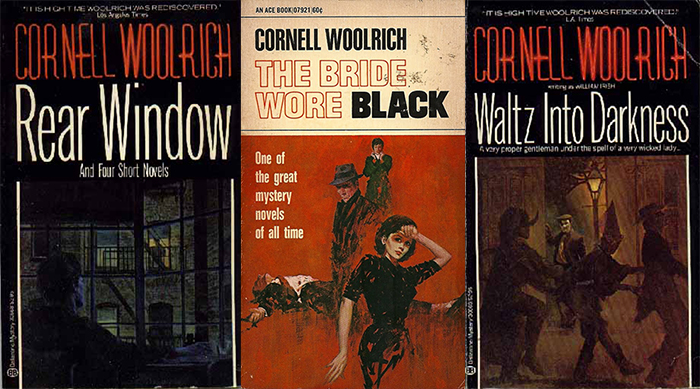

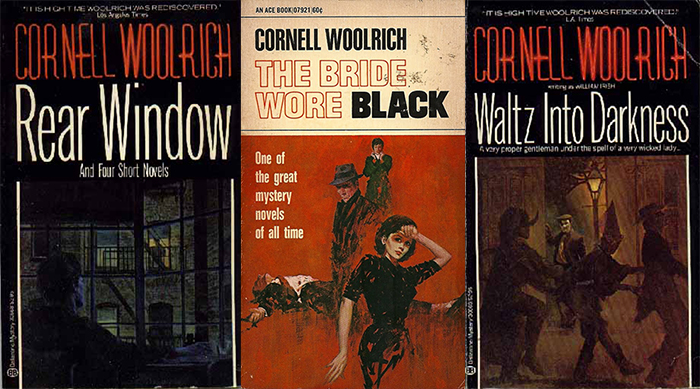

Another illusory connection between Bride and Hitchcock’s work is Cornell Woolrich, the American crime novelist who wrote both the source material for Truffaut’s film and Hitchcock’s signature film, Rear Window. On the one hand, this seems like an obvious imitative gesture by Truffaut, adapting the author behind his master’s defining film. On the other hand, no English-language crime writer has been adapted as frequently as Woolrich. There were more than 20 films made from his work in the 40’s and 50’s alone (the time period during which Rear Window was made.) Connecting to Woolrich is connecting to a novelistic/cinematic confluence far bigger than Hitchcock alone.

If he wanted to hammer a Hitchcock connection, why not adapt Daphne du Maurier, an English writer who Hitchcock had adapated three times with Rebecca, The Birds and Jamaica Inn - each film coming at a different phase of Hitchcock's career to boot? Plus, unlike Woolrich, du Maurier has rarely been adapated, Nicolas Roeg's Don't Look Now being the only other major take on her work - and Roeg's film didn't even come out until 1973. When Truffaut was putting his pastiche together, it would've just been him and Hitchcock laying cinematic claim to her. Could he have avoided du Maurier because both Jamaica Inn and Rebecca were notoriously tempestuous shoots for Hitchcock resulting in films that he more or less disowned? And that The Birds was one of the few misfires by Hitch that even Truffaut could only half-heartedly go to bat for?

That's a kind of empty speculation on my part, but I'm only indulging it to drive home the notion that there's not some special Hitchcock/Woolrich connection, even if Truffaut returned to the author again with his immediate "do-over" pastiche Missippi Mermaid. To my mind, the only novelist Hitchcock ever took on who could match his curdled sex-hatred of women was Patricia Highsmith (with 1951's Strangers on a Train.) If you want a writer who captures that essential part of Hitchcock, she's almost definitely your best choice. My only point is that Hitchcock adapated lots of authors, many of whom are easier to associate with a Hitchcockian sensibility: Winston Graham, the duo Boulieau-Narcejac, Robert Bloch. There's no special Hitchcockishness to Woolrich, who tended towards a glum fatalism with very little humor. His books are seedy with film noir's wrecked sentimentality, qualities it's hard to place in Hitchcock.

Plus, Truffaut told Le Monde in 1968, “I read the William Irish*** ** novel at the Liberation. I was about 13. I read a little in secret when I was alone in the house, because my mother had told me it was terrifying.” This would have predated the existence of the film Rear Window by about a decade - the book already had its impact on Truffaut before Hitchcock touched the author. Plus, Woolrich's style embodies a vein running throughout American cinema in the 40's & 50's, not just because he was so frequently adapted, but because it helped define so many of the tropes and tics.

The film follows a woman (Jeanne Moreau) who hunts down the five men who killed her husband on their wedding day. It’s told a bit out of order, jumping around in time between the tragedy, moments of extreme emotion (both in her youth and recent life) and the individual scenes of her exacting ice cold vengeance (i.e. the plot and structure are identical to Kill Bill!, just in case you thought Tarantino ever had an original idea.*** ***) There are superficial mysteries - “why does she want to kill these men?” “what is the tragedy that occurred?” “how does she know their identities” - but they’re either quickly resolved or dropped as narrative concerns entirely. This is one of the few concrete ways I can identify he was imitating Hitchcock, who insisted he didn’t make mysteries and said the MacGuffin needed to be destroyed well before the film was over.

The plot doesn’t sound particularly like a Hitchcock plot. He rarely made movies with stories that simple and direct. The first half of any given Hitchcock film is usually creating a cloud of confusion to disorient his heroes and the second half cutting through the fog. Truffaut’s film is both simpler and ultimately foggier than anything Hitchcock ever did, save maybe Vertigo, one of the true outliers in the director’s filmography. Hitchcock also didn’t make revenge films - a few of his characters are exacting a sublimated psycho-sexual revenge on womankind, but that’s almost always subtext (or a subplot.) Described bluntly, the murky plots of Hitchcock films reveal themselves to be “solve a murder” or “find the missing microfiche” or “prove one’s innocence,” not “get revenge.”

Hilariously (and ironically if you think he was consciously trying out a Hitchcock impression), Truffaut’s shoot went haywire behind the scenes. It was the first color film he had shot with Raoul Coutard (best known as the cinematographer on Godard’s early films) and by all accounts the two had endless fights about how the film should be shot. Additionally, according to Robert Osborne of Turner Classic Movies, Truffaut didn’t even end up directing the actors – Jeanne Moreau, one of the biggest stars in the world at the time, would constantly override his direction and work out the performances with her fellow actors outside of Truffaut’s supervision.

It’s hard to imagine a shoot more antithetical to Hitchcock’s ol’ “I have everything so planned out that when the time comes to shoot, there’s nothing to do, really, the movie just makes itself, I don't even need to be there, I could be off having a lemonade or something, really” shtick. Rebecca, of course, didn’t reshoot itself, that was Selznick: while stories about a director’s God-like autonomous generation of Cinematic Life are fun (and fun for any filmmaker’s ego) the truth is that film is the most collaborative of all arts and I’m willing to bet that Hitchcock wasn’t treating Jimmy Stewart, Ingrid Bergman or Cary Grant like goddamned cattle, cutesy quotes to the contrary.

The Cahiers image of The Master of Suspense, amplified by Hitchcock's own PR machine and then taken as simple fact by later critics, obscures reality from every direction. It’s tempting to say “sure, Bride doesn’t resemble Hitchcock, not really – look at how things went behind the scenes!” and think that’s a meaningful observation. But we know some of Hitchcock’s most esteemed films like Rebecca were beset with behind the scenes difficulties whereas with some of his worst (The Birds, Marnie) he had closer to complete control. Besides, you don’t need to dig behind the scenes to see the sharp contrast between Bride and just anything Hitchcock ever did. I mentioned it earlier, but I think the two filmmakers’ different approaches to women are what actually disqualify them from meaningful similarity.

Hitchcock’s classic heroine is a woman paralyzed by fear: a woman caught uncertainly between what she wants to be true and what she knows to be true; fear and anxiety being her static state. Suspicion, Spellbound, Shadow of a Doubt, Rebecca, The Lady Vanishes: when Hitchcock has a female main character, the story usually follows her process of confirming the world’s horribleness, the evil right there in front of her, frequently an evil that everyone else refuses to see. The classic Hitchcock heroine is afraid she’s crazy and her narrative process is confirming that she’s not.

When they’re not leads, Hitchcock’s female characters generally fall into a few basic categories:**** *** sidekicks who exist to be imperiled and eroticized (Notorious, Rear Window, North by Northwest), duplicitous villains (Vertigo), emotional outlets frustratingly indifferent to male suffering (Rear Window), total head-cases (Under Capricorn) or eroticized duplicitous head-cases who are frustratingly indifferent to male suffering (Marnie, Family Plot.) A lot of times, Hitchcock’s women are just bodies and it’s not clear he differentiates much between bodies draped in Chanel or dumped in channels.

A character like Jeanne Moreau’s bride just doesn’t have any analog in Hitchcock’s work. It’s hard to compare a character with such a weird emotional life to, say, Grace Kelly’s Margot in Dial “M” for Murder, whose characterization extends little beyond “I sure hope Ray Milland doesn’t kill me!” It’s telling that Marion Crane, one of his few characters to resemble a traditional film noir “ballsy broad,” gets murdered halfway into her own movie so the focus can shift onto an oppressive, emasculating mother figure. Hitchcock doesn’t have much interest in women steeling up and fighting back against the world, but is deeply concerned with the misery female control (or independence) causes in men.

The Bride Wore Black is the story of a fatalistic fight back against a tragedy that’s already happened, a story about fighting back even though the battle is lost from the beginning. There’s no way for Moreau’s Julie to redress the tragedy that has befallen her and her groom, only a stoic non-acceptance in face of reality. It’s an almost perfect inversion of Rebecca or Shadow of a Doubt – in those films, the arc of the story being the heroine’s acceptance and escape from evil that has invaded their everyday life. In Bride, acceptance would mean nothing. The tragedy cannot be mastered. Truffaut has compared his heroine to a ghost or a zombie, a supernatural figure imbued with metaphorical qualities about righteous revenge or re-visitation of past sins.

As a result, Bride plays more like a horror film than a traditional thriller and its resemblance to the rape-revenge genre which would emerge in the following decade is striking – in structure and tone, it’s the closest thing Last House on the Left or especially I Spit on Your Grave have to an antecedent. The rape-revenge genre is built on the ironic tension between the emptiness and the necessity of revenge. An easy comparison to Bride is Bergman’s Virgin Spring (the inspiration for Last House) where a respected cinematic artist seems to have ended up making a film in disreputable subgenre without necessarily intending to.

Both Spring and Bride explore an implacable need for revenge that’s entirely pointless – in Bergman, the emptiness of the revenge makes it a gesture against God; in the essentially atheistic Truffaut film, the gesture is eerie and hollow (a trip to the confessional actually gives her the strength to go on) – the only words to describe it are the same ones that you would use to describe a really effective horror film that stirs something in you that you will never be able to fully articulate: chilling, unsettling, disturbing, eerie.

It’s an interesting contrast because late in his career Hitichcock also found himself deeper in a disreputable territory than he intended, creating a precursor to a genre that hadn’t quite formed. In terms of the horror genre, Hitchcock’s most prescient work wasn’t the fundamentally inimitable Psycho, but the grotesque and pitiable Frenzy, a film which emphasized a leering emphasis on “kills” and haphazardly mixed sex and violence by failing to draw clear lines between an audience’s cheapest titillation and righteous repulsion.

Frenzy plays like a bad slasher, one of the cheaper Friday the 13th films designed without much in mind beyond giving teenagers some hooters to hoot at and sickening murders to either be sickened or amused or secretly aroused by. Because it’s Hitchcock, of course it lacks a final girl. Just thinking about the context of the horror genre when it was released, it’s funny to think it predates The Texas Chain Saw Massacre by just two years, so much more shocking and intelligent is Hooper’s film, the weird uncle to the slasher genre. Hitchcock’s film is unpleasant, cheap, and outdated, a junk-store relic, whereas TCSM feels like an alien transmission; visionary, but maybe the vision of a psycho-messiah. Hitchcock’s film presaged the slasher template but somehow aged as badly as the films that came in late 80’s, when the sub-genre was entirely creatively and morally exhausted.

The Bride Wore Black (and Virgin Spring and Texas Chain Saw Massacre for that matter) still play, they still really work; they haven't been made been obsolete by the art that followed, they're simply more thoughtful and stylish versions of what would follow. Frenzy, on the other hand, fits squarely in the ignoble traditional of British slashers. The country never seemed to get a handle on the genre and never discovered how the films could be vessels for political commentary (as in Craven or Hooper), showcases for cinematic virtuosity (as in Carpenter) or good clean mindless fun (what genre rules the “so bad it’s good” category more decisively than the slasher film?) British slashers have a tendency to be repugnant and cheaply made, the kind of films that really do seem they could only be appealing to perverts and malcontents.

As genre precursors, the gulf between Bride and Frenzy couldn’t be wider. The critical appraisal of Bride has fluctuated wildly over the years but from the beginning, there’s one thing everyone could agree on: it’s strange. It’s haunting and memorable in ways where it’s not clear what Truffaut intends for an audience to do with it. Frenzy, on the other hand, has benefitted substantially from the ever-increasing exultancy for Hitchcock: you will now regularly read how this plainly tasteless and thoughtless film is a wonderful expression of Hitchcock’s incontrovertible taste and meticulous cinematic forethought. Critics struggle (I struggle) to make perfect sense of the enigmatic Bride, but effortlessly imagine a false Frenzy.

Both are near-horror-films from filmmakers who rarely worked within the genre. Bride has an expressivity that’s hard to digest and the ability to bore its way into the audience and unsettle them. Frenzy repulses. Again, I think the difference between the Truffaut and the Hitchcock comes back to the main characters – even in dealing in the baseness of the horror genre (and I mean that in a good way!), there’s such a striking contrast between the forgettable leads of Hitchcock’s policier and Jeanne Moreau’s unforgettable bride.

With a tone that can only be compared to a horror movie, there's a sexual overtone enshrouding the bride's story. Again it's a contrast - this is one of the stranger things about Hitchcock: if you ask me, his movies are weirdy sexless affairs. For all the beautiful women in designer gowns, nubile young women struggling towards their first independence, sex crimes, indentity-loaded dress-up and gender confusion, there sure isn't a lot of fucking in Hitchcock's movies, or even a chaste Hollywood in 50's intimation of fucking. They're not even sensual films. He loved ice cold blondes and female fridity was undoubtedly one of his main obsessions.

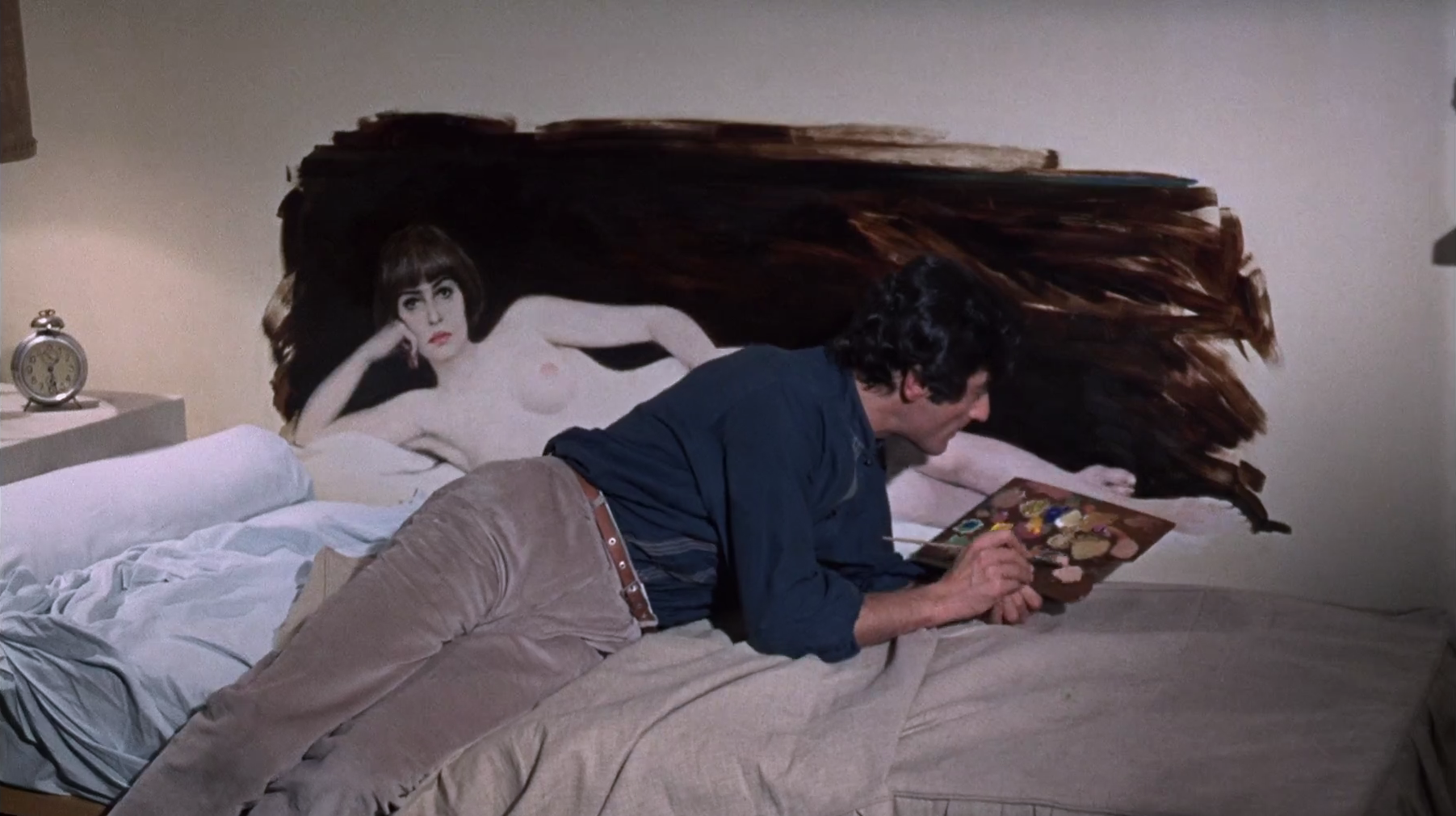

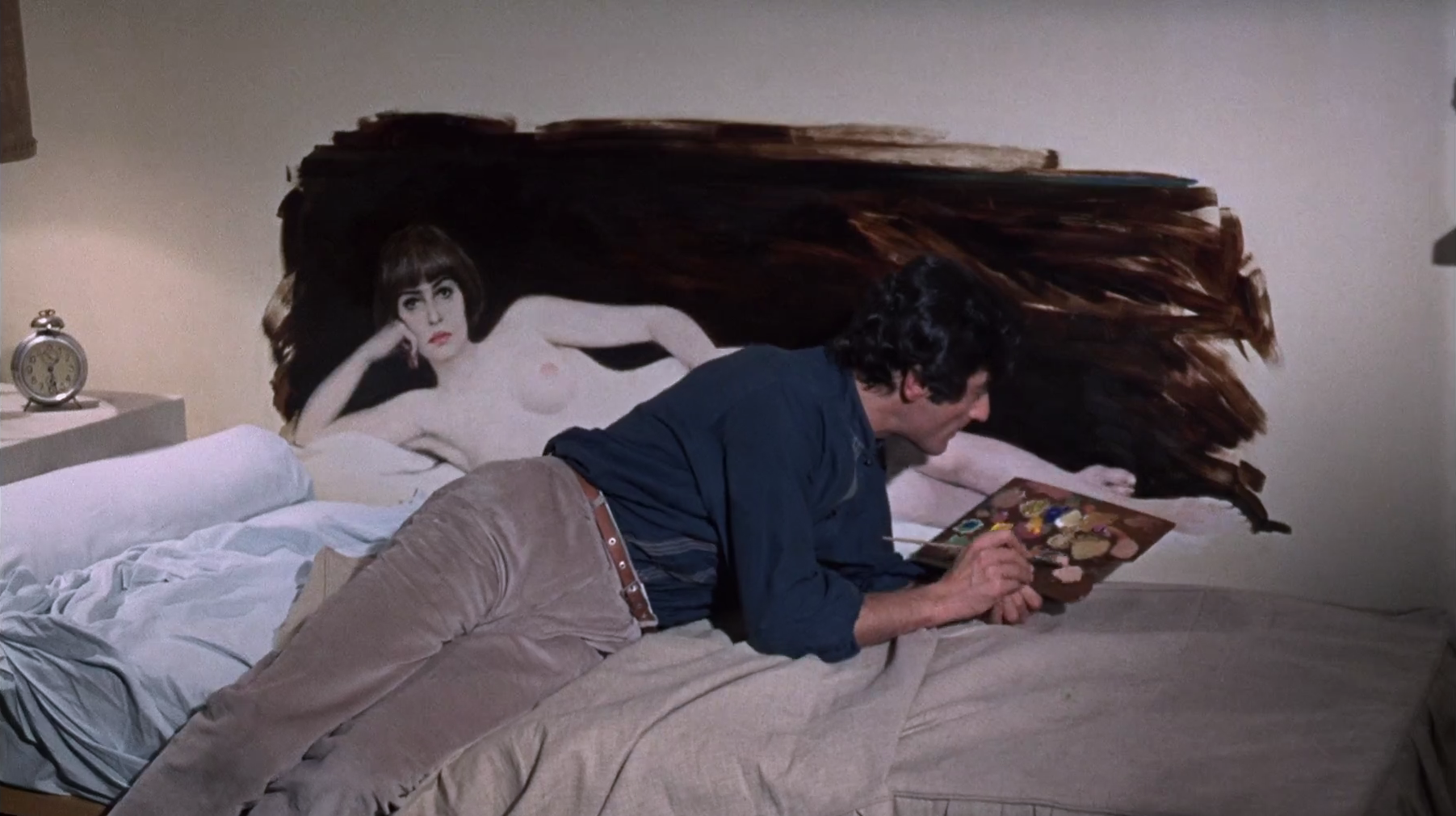

Bride on the other hand is rivaled only by Madamoiselle for taking advantage of Moreau's hard-to-classify erotic energy as a disruptive force. She has a vampire's threatening and otherworldly sensuality and in Bride it's ramped up to full force while perversely remaining inaccessible, cloistered. Her heavy lips and the inexplicably sensous bags under her eyes combine with emptiness of the character to create a hollowness to the eroticisim of the film, a haunting, hypnotic force that compells both the audience and the other characters alike. No wonder in the film's most famous sequence an artist chooses her as his muse and dresses her up as Diana the Huntress in a vain attempt to control and channel her coercive sexual power. The contrast between Hitchcock's un-possessable women and Truffaut's un-possessable bride is striking.

Truffaut told Le Monde: “She thinks of only one mission: to avenge her husband.” Characters with monomaniacal focus are rare in Hitchcock – that is, the desires of Hitchcock’s characters are generally circuitous, sublimated, concealed. What his spies, psychos and conmen all have in common is that it’s rarely entirely clear what they’re about and their stated missions are often covers for more abstract or duplicitous goals. His big guns like Strangers on a Train, Rear Window, Vertigo and Psycho all deal with the ways perverse desires are channeled into other expressions, even the obsessive Jimmy Stewart characters in Window and Vertigo are engaged in missions that only obliquely touch on their true mania. And as I mentioned with his heroines, they are resisting themselves; paralyzed by fear, unable to accept.

Interestingly, his famous "wrong men" are perhaps monomanical in their pursuit of proving their innocence, but those stories often begin with these characters not understanding what they're being accused of or why - their desires, their aim, their focus, gets tossed this way and that. What they're after and what they're about shifting the stakes of the story and forcing it to constantly refocus. And furthermore, their obsession is by its nature not about what they are, but what they are not. Henry Fonda in The Wrong Man is obsessed with the robbery of an insurance office only as a way of proving he has no interest in the robbery of a insurance office.

I’m struck by one final quote from Truffaut, speaking to Sight and Sound in 1967: “This film is absolutely not a portrait of a woman. Jeanne Moreau is the central character, but even at the end we still don’t really know anything about her.” This is a very strange description of the film and I think a lot about what Truffaut meant by it. It's strange because the film is focused so squarely and unrelentingly on the bride. I don't think it's outlandish to say we know as much about her as we know about any character in any film. I think Truffaut is simply trying to articulate that there’s something compelling about the bride in the abstract, that she possesses the metaphorical capacities of a horror trope - what’s compelling about her can’t be fully articulated.

When in early the film, she appears drapped in white, she's got a breath-taking ethereal quality like a specter or a demon affecting an angleic mien. Like the goofball janitor (another empty Hitchcock nod), we're stunned by her presence in a way that doesn't fully make sense. Sure, her glamour is overwhelming and out of place, so much so that it's almost but not quite logically sinister and disturbing - but it's also inviting, irresistable. There's a unsettlingly celestial quality to her, the idea of an incomprehensible demi-God come down to earth, driven home by her conversion to Diana at the end. She's a huntress, stalking with the inscrutability of a supernatural force that draws us to it; awe, but awe-ful. Of course she disappears at the end of the scene, leaving the maintenance man looking around in confusion.

It’s insane to say “the film is absolutely not a portrait of a woman” when it is almost nothing but a portrait of a woman, but it is also true. She’s fundamentally unknowable, like a ghost. Even as I research this piece, I am shocked by how little useful criticism exists on the subject of Bride – it’s a strange film, one with its meaning locked tightly away in a vault. I’ve yet to come across a critical key to unlocking it, so zeroed in on the meaningless connection to Hitchcock are any discussions of it (like this one!)

I think at the end, we get to the truth: the Hitchcock comparison feels externally imposed by critics. It’s tough to find an interview where Truffaut dwells on the comparison, although almost every interviewer brings up the subject of it being a Hitchcock homage. Although he insists this is true, that it is an homage, Truffaut has almost nothing to say about how it’s true - a remarkable fact for a man as garrulous and specific as Truffaut. In these interviews, he’s much more likely to talk about fairy-tales and creating a dream-like atmosphere, which immediately feels closer to the truth than anything to do with Hitchcock. Fairy-tales are the ancient ancestors of horror films, after all.

Ever looking back, he seems caught in capturing how this terrifying book made him feel at age 13 during the Liberation, the dreaminess he insists is a tangible facet of Woolrich’s book more likely a phantom of his adolescent fear at a time of incredible cultural anxiety, of sneaking a glimpse at a terror that was forbidden to him. His film of The Bride Wore Black works through his young memories of experiencing the book, the film an attempt to capture a specific psychological and emotional state now only accessible through a haze of anamnesis. Woolrich’s novel stirred in him the same emotions a fairytale stirs in any child. What is our adult relationship to those childhood fears?

The story is only dimly remembered (he told interviewers he wasn’t sure he had, in fact, read Woolrich’s book before deciding to adapt it) and retold navigating the fog of memory – I think what Truffaut has done with his film is capture that emotion, capture that state: the adult still feeling a childhood fear, the adult still holding a childhood emotion. The bride’s revenge is unintelligible and deeply felt, the way a childhood emotion can be unintelligible and deeply felt forever after. The adult pantomime, the ritualistic working through of this childhood emotion, this re-working that occurs over and over, in repetition; five murders - one revenge, one revenge, one revenge, one revenge, one revenge.

The insight it gives us into Truffaut is that the each assassination is structured as a flattery of a male fantasy of feminine purpose: a secret admirer that tempts you from your fiance, a mysterious seducer boldly suggesting an afternoon tryst, a mother-figure doting on you for a domestic evening in the suburbs, a tramp who won't take "no" for an answer, a muse that seizes your erotic imagination, the silent servant who brings to you your daily bread. An invisible line between deserved victimization and fantasy fulfillment; it is an adolescent terror that your desire will result in your destruction.

Truffaut uses Woolrich’s story to express an idea entirely outside of it: Truffaut’s sense of his own youth, the essence of his youth that plagued him until his death, the ways we try to make sense of how we have become ourselves while repeating over and over youthfully-sourced behaviors that seem meaningless, futile. What makes Hitchcock/Truffaut timeless and essential (in comparison to, say, Rohmer & Chabrol’s fine book on the British auteur) is that Truffaut’s voice is every bit as important to the conversation.

It is a portrait of a great filmmaker trying to understand his idol as much as it is a portrait of Hitchcock himself. The Bride Wore Black may very well be a Hitchcock homage, but Truffaut’s own voice entirely drowns out whatever conversation he may be having with his master. For Truffaut, the most important part of Hitchcock/Truffaut will always be /Truffaut. How could it be otherwise?

~ NOVEMBER 22, 2016 ~

* This is your opportunity to tweet something coolly dismissive of the very concept! Do it! You’ll be an internet hero for your noble defense of the much-maligned Alfred Hitchcock! Take this bold stance now - sneer, snark and shrug in a gesture of dismissive superiority! "People write some crazy stuff on the internet," you'll tweet and you'll put a little whattayagunnado emoji next to it and everyone will think "Well there's a guy who knows movies. Not like those guys who think Torn Curtain and Under Capricorn are terrible." I just hope someone out there has the courage, integrity and intelligence to take this stance. Our willfully provocatively iconoclasm would be empty without an establishment orthodoxy to stick it to!

Or just, like, accept that not everyone likes the exact same movies that you do. It happens. Also, I really wanted to write "Sure, you'll blanche like the sluttiest Golden Girl at the suggestion," but Cribbs pointed out this series already isn't doing the site any favors even without a truly moronic Golden Girls joke in the intro. The fact of the matter is, we know our opinion on Hitchcock will be unpopular and we'd just like to move past it. If you think our assessment of The Great Big Fat Scare Maestro (that was his nickname, right?) is indefensible, just know we have no desire to defend it.

* These films, along with the wondrously hateful Shadow of a Doubt, are his most interesting movies, but that’s another discussion. That discussion also involves addressing the eternal Hitchcock debate of “are his films explorations of misogyny or expressions of misogyny?” The answer can be “both” of course (and it’s not unreasonable to argue that is the case with Shadow of a Doubt or Marnie) but it’s absurd that anyone would argue the late Hitchcock films are anything but indulgences in seething, thoughtless anger. Using the early films as defense against that idea is a common trick to deny it, though: "The early films aren't thoughtlessly angry at womankind, therefore the late films cannot be either!" Part of the reason Hitchcock is no fun to write about is that no filmmaker in history, apart from maybe Tarantino, has more been the beneficiary of ludicrous and bullshit defenses than Hitchcock. There’s just a whole 7 seas worth of bad criticism extolling his virtues and explicating his genius, starting with the frequently disingenuous and slyly specious Cahiers du Cinema writers. I mean, critics by and large are fucking worthless – can you believe I have to live a goddamned world where Laura Mulvey’s dipshit garbage about the Freudian symbolism of Hitchcock’s filmmaking is to this day a touchstone theory on the meaning of his work? What I’m saying is: you won’t catch me denying the seething hatred behind this footnote.

** Movies like the later Doinel films, The Soft Skin, The Man Who Loved Women, The Woman Next Door and Confidentially Yours are all caught up in the relationship between "loving women" and the inherently detestable qualities of womanizing.

*** The list of films for which he was nominated is fascinating: Rebecca, Lifeboat, Spellbound, Rear Window and Psycho. The Academy seemed to want to reward him for his most gimmicky work - Rebecca is the only film in the list that resembles the kind of Prestige Project for which directors are usually nomiated while films like Lifeboat and Spellbound have some of his biggest, dumbest hooks. "It all takes place on a lifeboat! The dream sequences aren't window-dressing this time, they're the key to the mystery... and Dali designed them!" I do think a base horror film managing to get nominated for anything is a testament at least in part to the influence the Cahiers critics had by 1960, a moment simultaneous with Truffaut's 400 Blows and Godard's Breathless blowing up world cinema and, indeed, our conventional notions of conventionality altogether.

But quantifying a director's reputation is tough - compare Hitchcock's nominations to contemporaneous filmmakers like Billy Wilder (8 nominations, 2 wins), John Ford (5 nominations, 4 wins), Frank Capra (6 nominations, 3 wins) or Wyler (12 nominations, 3 wins) and you'll see that Hitchcock was respected but just not quite to the level of his peers. I don't think I'm being controversial to say that his outsized reputation as the master of masters was created post-facto, although I do think the idea gets overplayed that he was a chump who the Cahiers dudes made. As far as his reputation in the 40's and 50's, I think a good comparison would be to another off-beat artist like John Huston (5 nominations, 1 win) who managed to operate within the studio system as something of a beloved sideshow - history has also been extremely kind to Huston.

By the way, sometimes when I write an extremely long and weirdly detailed footnote like this, I'll wonder who I'm arguing with and for what? Clearly, I don't think the tangent belongs in the article - not necessarily that it isn't important enough for the article, but because I just know it's off-topic enough that it would disrupt the flow and ruin all of the great fun we're having here today. But then something like this happens where I'm obsessively detailing Oscar wins and trying to quantify just what I mean about "Hitchcock being estemed, but not really esteemed until the Cahiers critics came along" which is an orthodox take. There's no one who would disagree with that. I don't need to argue to that completely usual perspective. But I think maybe I disagree with the standard take so you have to watch me convince myself in slow motion and then when I'm done, well I've already written all this stuff and it's kinda interesting so I might as well leave it in, right? But all to convince an nonexistent audience of something that almost everyone would accept as true.

I don't know what the hell I'm doing here.

** ** To my untrained ear, Fahrenheit 451’s score is much more traditionally Hitchcockian: its main suite has delicate strings moving in a delirious rising and falling action; it stutter-steps to a precipice. Other sections feature heavy, stabbing strings that are virtually impossible not to associate with Hitchcock and the "love theme" has a brief run of melody that can only be a deliberate homage to Vertigo. Bride’s score has a bombastic quality combined with the sarcastic take on Mendelssohn's wedding march and even experimental noise elements (the way the opening credits make music out of the sounds of the photo-printer); it's driving and orchestral with thundering horns that drop suddenly into moody quietude, almost like a Wagner parody. It’s hard to imagine it fitting into a Hitchcock film. Moreau's recording of Vivaldi's Mandolin Concerto in C dominates the film way more than Hermann's score, anyway.

*** ** William Irish was Woolrich’s pseudonym – I’m not sure what’s going on here with Truffaut referring to it as one of the “Irish” novels, when I’m almost 100% certain it wasn’t published under that nom de plume (I am 97.6% certain.) Weirdly, there are conflicting reports all over the place about which named was used for its original printing and I think Truffaut’s constant references to the book as being written by “William Irish” are the source of this confusion. But I don’t know what the situation was with author accreditation in France – in the same Le Monde interview, Truffaut mentions it was published there under multiple titles, so who knows what’s what but a cursory amount of research doesn’t turn up much clarification. I’m not willing to research it any further beyond “cursory.”

*** *** Yeah, I know he claims never to have seen it. Let’s just say I’m dubious that a notoriously voracious video store clerk who named his production company after another French New Wave crime film who is famous for re-appropriating elements from other filmmakers just happened to make a movie that is identical in both basic story and non-chronological plot structure, heavily reminiscent both in broad strokes and specific details, to a film he’s never seen based on a book by an author he’s professed admiration for. I mean, there's even a scene where one of the victims is stalked in their suburban kitchen along with their young child - the kitchen is even laid out the same way as in Kill Bill. On the other hand, he admits when he steals, right? I honestly don’t know. Does he say “oh yeah, that’s totally Lady Snowblood there!” or “of course I was thinking of City on Fire!” or whatever when asked? Or does he say, "Thriller.. A Cruel Picture? Never heard of it!" I have no idea.

**** *** There are a few exceptions, of course, like the Priscilla Lane character in the Joan Harrison & Dorothy Parker scripted Saboteur, who resembles a screwball comedy heroine in a film that's one of Hitch’s more overtly comedic thrillers. Harrison was a frequent Hitchcock collaborator - one of the things that fascinates me most about the undeniably misogynistic Hitchcock is how consistently he worked with female screenwriters and adapated female authors.