3/22/2007 - 3/31/2007

christopher funderburg

In October 2006, Funderburg and Cribbs set out to watch at least 200 movies over the course of the next 200 days. They both watched a different slate of films and wrote about every single one; from epic high art masterpieces such as Fassbinder's 15 & 1/2 hour Berlin Alexanderplatz to goofy teen comedies like Savage Steve Holland's worthy One Crazy Summer to idiotic dreck like Open Water 2. In sections spanning 10 days at a time, The Pink Smoke is reprinting their writings about the grueling experiment in cinematic endurance.

<<click here for 3/12 - 3/21>>

3.22.

I was supposed to see Zodiac, but fell ill and went to bed at 9:15pm.

3.23. I Think I Love My Wife.

(35mm) City Cinemas 86th St.

Chris Rock's adaptation is the most unfortunate kind of film: it is a surprisingly intelligent, faithful remake of a well-regarded film. It is interested in engaging reality in a sincere fashion, it is unpretentious and frequently very funny. It features attractive, likable actors working with a thoughtful script and doesn’t ever shy away from the themes and ideas that its plot raises. It is a film that can be treated as a real film and not simply as garnishing for popcorn sales. Which makes its mediocrity all the more painful: if this were simply another big, dumb Hollywood comedy, it would deserve all the praise in the world: its ambitions are light-years ahead of Music and Lyrics or Are We Done Yet?; it's more mature, refined, and worthy of serious contemplation than any film Adam Sandler has ever made, combined (including the aesthetically adventurous but essentially juvenile Punch Drunk Love) and it is certainly playing in an entirely different league than Rock's own CB4, Osmosis Jones, and Head of State.

Chris Rock's adaptation is the most unfortunate kind of film: it is a surprisingly intelligent, faithful remake of a well-regarded film. It is interested in engaging reality in a sincere fashion, it is unpretentious and frequently very funny. It features attractive, likable actors working with a thoughtful script and doesn’t ever shy away from the themes and ideas that its plot raises. It is a film that can be treated as a real film and not simply as garnishing for popcorn sales. Which makes its mediocrity all the more painful: if this were simply another big, dumb Hollywood comedy, it would deserve all the praise in the world: its ambitions are light-years ahead of Music and Lyrics or Are We Done Yet?; it's more mature, refined, and worthy of serious contemplation than any film Adam Sandler has ever made, combined (including the aesthetically adventurous but essentially juvenile Punch Drunk Love) and it is certainly playing in an entirely different league than Rock's own CB4, Osmosis Jones, and Head of State.

But the catch is that you can't judge it on the level of those films – it's just good enough that even though you want to praise it, you simply can't. You owe it to the filmmakers to not shy away from engaging it on a deeper level of criticism: the film earns a thoughtfully negative review. Much like the Eric Rohmer film upon which it is based, I Think I Love My Wife at first glance appears to be about infidelity, but its true subject is actually fidelity – it's not about the desire to have an affair, but the uneasy allegiance into which one enters upon marriage (or serious commitment): it is the moment your life goes from existing in a constellation of infinite possibilities to a definite future. Both films follow a button-down businessman presented with the opportunity to a bed sensual, free-spirited woman who happens to not be his wife. The film considers how much either situation is really an illusion: is the married man's future genuinely immutable? Or does every affair consciously passed over represent a new choice and constellation of possibility?

Much of the ideas and themes are translated directly from Rohmer's film, Chloe in the Afternoon – and it's only fiitng that Rock's film (co-written by Louis C.K.), so deeply concerned with fidelity, would be so faithful to the source material. There are whole sequences lifted from the original, but even a flurry of small details - from the metropolitan vs. suburban setting conflicts to the occupation of the main character's wife -are left intact. Like most happy couples, at first glance the union between Rock and Rohmer might not seem like the most logical marriage, but closer inspection reveals significant, hidden connections (and Rock and C.K. also exhibit a great deal of respect of Rohmer's film; respect, of course, being a key component to any fruitful relationship).

Rock's stand-up comedy has always focused on mainly two things: race and relationships. However, Rock's perspective on race has always been identifiably independent from many of his peers (especially the "Def Jam" style dominant amongst black comedians during Rock's rise to fame): from his earliest days, Rock has always been defiantly middle-class in his perspective; his infamous "I love black people, but I hate niggers" bit inadvertently revealed the hidden philosophy of millions of middle-class white people who hated to think of themselves as racist – the unexpected connection between Rock's bit and the thought-process of guys who wear ties to work reveals a class conflict more than a racial one: the white people who loved it genuinely wouldn't have a problem with seriously befriending a black man (or even having one marry their daughter), so long as that black man wore a tie to work as well.

Rock's take on relationships is similarly infused with a middle-class perspective: he worries about balancing work and family, about finding the "right" woman, about making a marriage work. Rock's popularity illustrates the strange fact that thoroughly "black" language and pop culture is longer in any way in conflict with the middle class language and ideals; co-opted "black" style is a major part of the middle-class pop cultural experience: he not only speaks about middle-class anxieties, but also does so in middle-class friendly terms. And, of course, Eric Rohmer is himself the Poet Laureate of bourgeois anxiety. Rohmer makes films about the exact same minutiae with which Rock is concerned: the tenuous stability of middle-class existence and the light comedy of relationships, money and sex to be mined from that rich vein. The wry, wistful perspective of Rohmer's work isn't light years away from the conflicted, sarcastic tone of Rock's film. The main differences are that Rock adds racial concerns and Viagra jokes: the feather-light irony that is Rohmer's signature is replaced in Rock's film with too many sledgehammer blunt jokes about Michael Jackson, club-hopping and furniture shopping. You see, men want to drive convertibles and women want to buy mini-vans! Men want to talk about blow-jobs and women want to talk about carpet samples! Some of this stand-up comedy-esque material is funny and some of it is not so funny.

Fortunately, Rock leaves the structure of Rohmer’s script essentially intact, so that the overall film has some cumulative power. Kerry Washington's performance as the Chloe surrogate (here given the borderline laughable name "Nikki Tru") is a perfect mixture of sexy, charming, and obviously devious: her readily apparent amorality makes her connection with Rock believably appealing and clearly dangerous. On the flipside, I wish Rock's wife weren't so much of a one-note nag, it's hard to root for him to stay with her – even if you don't want him to sleep with the heaping bag of trouble that is Nikki Tru, you at least want him to escape the humorless henpecker back at his bland two-story in suburban Connecticut. The final scene has is a punctuation mark of out-of-left-field warmth and goofball humor that you wish you could've at least had a small taste of at some point earlier in the film – you understand why Rock loves his wife. It works, but it also highlights one of the film's major flaws: the generally flat, almost misogynistic characterization of Rock’'s wife. You see, she wants to buy big, beige panties Anyway, Rohmer never had a repressed businessman peer-pressured into smoking up by two improbably flirtatious hot chicks, losing his inhibitions (and loosening his tie) and then dancing goofily to "Shake that Laffy Taffy."

3.24. The Hills Have Eyes II.

(35mm) CC Village East.

Not so much a remake of the original The Hills Have Eyes II or even particularly a sequel to 2006's The Hills Have Eyes remake so much as it is a rip-off of Predator, THhE II follows a small task-force of soldiers investigating the disappearance of some scientists and military personnel in a remote, treacherous location. Despite their guns and training, the group is picked off one-by-one by the powerful semi-humanoid beasties hunting them. I mean, add "Shane Black tells some jokes" to that description and you've got mother-fucking Predator.

Anyway, for a split second I thought this movie might be good as it opens with a regular pregnant woman chained to bed, giving birth to a deformed, mutant baby. "Ooh, that’s kind of fucked up!" I thought. Then I quickly remembered that the ol’ "fucked up mutant baby" thing is a shtick that goes back at least as far as Larry Cohen's seminal It's Alive and pops up as recently as in the similar sequence in the Dawn of the Dead remake. Oh, well. There's nothing to particularly recommend this movie – if you're looking for a moment or two of poetic, grotesque beauty (the tone of the trailer) or even cheap thrills and, like, plenty of them and it doesn't matter how tawdry or vacuous they are, you will still be disappointed. The movie's general conceit is "what if F-Troop ended up fighting a bunch of Toxic Avengers? Wouldn’t that be fucked up?" However, the answer to that question is that it would, in fact, be stupid and boring.

I kept on thinking that I recognized the male lead from somewhere, but I think it's just that he resembles Jeremy London. He's certainly about as talented as Jeremy London. Anyway, the film makes a half-hearted attempt to be depraved - there's even a rape scene halfway through the film. However, the film shies away from the rape just enough to make it feel really exploitative – it just seems to be in poor taste, as opposed to disturbing, like the film wants to get credit for being all fucked-up, but is too namby-pamby to go the whole way with it. It just makes the filmmakers seem like weak-minded pussies who are too hapless to even make their mutant hillbilly rape scene upsetting. Speaking of that, though, I have no idea what a movie has to do anymore to get an NC-17 rating. After seeing this film and Jackass 2, it seems to me impossible that there's anything left that's actually able to cross that line.

TMNT.

(35mm) CC Village East.

One of the defining characteristics of my generation is undoubtedly its exaltation of the regressive nostalgia for the pop-culture of our shared childhood. That's why the disappointing Star Wars prequels were more than just a series of shitty movies, they were the betrayal of one of my generation's most esteemed cultural values (the Star Wars films being the ultimate representation of our regressive nostalgia). Ask just about any dude born in 1977 what they think of The Phantom Menace and you will be treated to a diatribe not just about how much it sucked, but about how it tarnished something larger and more important than simply a trilogy: "The Phantom Menace and George Lucas raped my childhood." In other words, the crummy film attacked their cherished memories.

And the regressive nostalgia epitomized by Star Wars isn't just an isolated phenomenon, but rather a way of relating to reality repeated in miniature variations over and over within my generation: just glance at "Ain’t it Cool News" and you’ll be treated to a mass of voices wailing in agony that Michael Bay's upcoming Transformers has a deep responsibility to exhibit an unflinching fidelity to the source material: this was more than a dull, poorly animated half-hour commercial for toys, this was my childhood, man! And really, you can find this way of relating to the world repeated in diminishing circles on down to the small cults that enthuse endlessly over the likes of "Kid Video" or The Secret of N.I.M.H. None of these cultists would make the claim that these are worthwhile works of art that they're gushing over, rather they're implicitly making the claim that all media has passed from the realm of "art" and into the realm of "culture." A work"s relevance is located not along a scale of "quality" but of "shared experience" – it doesn’t matter whether these cartoons and blockbusters and bits of commercial ephemera are good or bad, it only matters that they were experienced by you and by others in a formative stage of your life. Truly, the very fact that so much of this garbage is so obviously bad and cynically designed to see toys or candy or fast food, that fact of these works’ inarguable crappiness is exactly what allows the audience to render the scale of "value” secondary).

They captured your imagination (and a child's imagination is not a very well-defended citadel) and imposed their sovereignty. There's no denying that this way of understanding media has become commonplace; have you ever actually tried to discuss the merit of Star Wars with someone in their late twenties? The discussion will explicitly never be about the quality of the film – to bring it up would be to step out of bounds. Something like TMNT is specifically designed to appeal to this regressive nostalgia while at the same time, hopefully, inspiring a future generation of nostalgists. That all said, I guess it's pretty apparent that I don't have much sympathy for that brand of childhood nostalgia – it seems both idiotic and depressing to me. Who wants to hold onto the mindset and world-view they had when they were seven? Does a semi-detached, ironic self-awareness of the fact that these cartoons were cynically designed to "move product" make a continued willingness to buy that product somehow more acceptable? "It's big dumb robots, I know it sucks - but why would that matter?" That perspective is just depressing.

But, if there were any bit of media designed to"“move product" to which I would be sympathetic, it would be the Ninja Turtles. They were the thing with which I was obsessed a kid, the "Mars Bar Quick Energy Choco-bot Half Hour" to which the citadel of my imagination willingly and enthusiastically submitted. So, it's a great relief to tell you that I actually liked this movie because I think that it is actually pretty good and has several elements of value to recommend it. First off, it features the best looking CG-animation I've seen in a feature length film outside of the gold standard set by Pixar. It's certainly a noticeable notch above the muddy, drab look of films like Shrek or Ant Bully and mercifully lacking the creepy sub-human qualities of The Polar Express or Monster House. Secondly, it has an attention to character design that is totally refreshing: so much of what's visually exciting about this movie is that the heroes, villains, and assorted beasties in between aren't simple retreads of previously imagined concepts (there is a monster that seems to be intentionally designed to recall King Kong, but that's really as close as it gets to re-treading pre-existing concepts). The monster designs reminded me most of the work of Guillermo Del Torro, a filmmaker whose greatest strength continues to be his vivid creation of singular and memorable creatures.

But, if there were any bit of media designed to"“move product" to which I would be sympathetic, it would be the Ninja Turtles. They were the thing with which I was obsessed a kid, the "Mars Bar Quick Energy Choco-bot Half Hour" to which the citadel of my imagination willingly and enthusiastically submitted. So, it's a great relief to tell you that I actually liked this movie because I think that it is actually pretty good and has several elements of value to recommend it. First off, it features the best looking CG-animation I've seen in a feature length film outside of the gold standard set by Pixar. It's certainly a noticeable notch above the muddy, drab look of films like Shrek or Ant Bully and mercifully lacking the creepy sub-human qualities of The Polar Express or Monster House. Secondly, it has an attention to character design that is totally refreshing: so much of what's visually exciting about this movie is that the heroes, villains, and assorted beasties in between aren't simple retreads of previously imagined concepts (there is a monster that seems to be intentionally designed to recall King Kong, but that's really as close as it gets to re-treading pre-existing concepts). The monster designs reminded me most of the work of Guillermo Del Torro, a filmmaker whose greatest strength continues to be his vivid creation of singular and memorable creatures.

Also, all of the action scenes in the film are smoothly rendered and inventively composed (you can actually tell what the hell is going on in a fight scene as opposed to in something like, say, Batman Begins, where you can through only tell that underneath the shaky, hyperactive stylistics that someone got punched) – it's one of the best Wuxia Pian ever made outside of Asia and can stand alongside some of that genre's better works. My main complaints are the frequently irritating voice-acting (it's beyond me why you would have Sarah Michelle Gellar, an actress whose worst quality is her inexpressive voice, do a cartoon) and the quickly-wrapped up plot: the bad guys go from awe-inspiringly powerful to hastily defeated chumps in a matter of screen-minutes. But really, isn't this discussion beside the point? Does the film have an unshakable fidelity to the Laird/Eastman comic books or capture the goofy flavor of the popular Saturday morning staple? Or maybe it returns to the "dark" tone of the much-beloved original live action film? Is it an awkward collision of all-three, unable to make up its mind as to which cult of nostalgia currently has the most credibility and cultural cache? Fortunately, those questions can be beside the point and the film doesn’t instantly wither under the light of "quality." It makes you feel like not even putting "quality" in quotes.

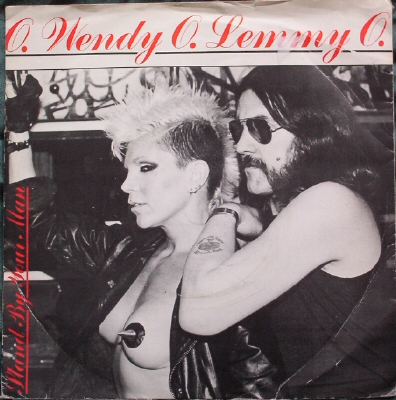

3.25. Wendy O. Williams and the Plasmastics.

(dvd) Megan Bennett's apartment.

An inadvertently fascinating "for the fans" documentary about Wendy O. Williams, the late 70's/early 80's cultural oddity (whom I knew virtually nothing about), this film is notable only for its subject matter. Even though my only firsthand familiarity with Williams was through a videogame homage (Wendy O. Koopa from "Super Mario Bros. 3"), I'm really glad to have gotten a good taste of the giant screaming mess that was her career. Even on the barest surface of things, she was contradictory and perplexing lady: she gained notoriety fronting the confrontational conceptual art outfit The Plasmatics before parlaying her early NYC punk notoriety into a fat contract with Columbia Records and an attendant image refinement that couldn't jive less with her initial exhortation to "fuck the status quo." Her pop cultural position is particularly unusual: she straddled the line between metal and punk when the two scenes hated each other and managed to be well-respected by both radical feminists and famed K.I.S.S. lecher Gene Simmons.

It's a shame that the hagiographical approach this film takes smoothes out so many of the jagged edges of her story – there's a clearly a lot going on beneath the surface that the film never bothers to touch upon. I mean, what kind of film about Wendy O. Williams makes absolutely no mention of her 1998 suicide? Or her infamous start as a stripper and porno actress? That aside, the element of her story that I find most strange and troubling is notion of the authorship of her persona. Of course, by the time any artist reaches the point of a major label contract, there's going to be an amount of careful shaping of their public persona (for anyone who went to SUNY Purchase at the same time as me, just think of Regina Spektor's transformation from dowdy coffee-shop warbler to VH1-approved quirky sexpot). And for someone like Williams to reach that point – someone who was far more notorious for her raw, downtown, heavily sexualized image than any of the music The Plasmatics created - the Columbia-era emphasis on the sexuality and "hardcore credibility" over the political provocation and concept art is hardly a surprise. By the time Simmons is producing her albums and she's abandoned her leather S&M gear and trademark colored Mohawk in favor of a blonde-ponytail and grey spandex, it's hard to not roll your eyes at yet another example of a conglomerate squeezing everything unique and subversive out of a polarizing figure.

It's a shame that the hagiographical approach this film takes smoothes out so many of the jagged edges of her story – there's a clearly a lot going on beneath the surface that the film never bothers to touch upon. I mean, what kind of film about Wendy O. Williams makes absolutely no mention of her 1998 suicide? Or her infamous start as a stripper and porno actress? That aside, the element of her story that I find most strange and troubling is notion of the authorship of her persona. Of course, by the time any artist reaches the point of a major label contract, there's going to be an amount of careful shaping of their public persona (for anyone who went to SUNY Purchase at the same time as me, just think of Regina Spektor's transformation from dowdy coffee-shop warbler to VH1-approved quirky sexpot). And for someone like Williams to reach that point – someone who was far more notorious for her raw, downtown, heavily sexualized image than any of the music The Plasmatics created - the Columbia-era emphasis on the sexuality and "hardcore credibility" over the political provocation and concept art is hardly a surprise. By the time Simmons is producing her albums and she's abandoned her leather S&M gear and trademark colored Mohawk in favor of a blonde-ponytail and grey spandex, it's hard to not roll your eyes at yet another example of a conglomerate squeezing everything unique and subversive out of a polarizing figure.

Predictably, the film is very quick to proclaim her early punk work an authentically dangerous feminist gesture – several academic experts are trotted out to vouch for her credentials on the subject – but just as quick to gloss over the fact that her "authentically dangerous feminist" bit was entirely conceived of and executed by a man: Plasmatics founder and leader, Rod Swenson. Swenson scripted the stage act (which included cars being blown up, cross-dressing, extravagantly pornographic gestures, guitars being chain-sawed in half and Williams wearing nothing but shaving cream), wrote the songs, even designed the album sleeves. Was the change that took place in Williams’ persona as simple as dropping the subversive element to sell-out on a major label or was Williams just a puppet all along, a Mohawk and a stage show, a killer body with no content? As Biafra says, "a hairstyle’s not a lifestyle," but there's plenty of evidence that she at least believed the words Swenson put in her mouth: she was a committed vegetarian, willing to be constantly arrested for what she believed in, and (by all accounts) lived the dominating, empowered sexual image she projected.

By presenting her story in a straight-up "rise to fame" account, the film does literally nothing to disentangle all of this mess – it's downright weird that the filmmakers feel no need to reconcile the genuinely bizarre and disturbing early Plastmastic stage-shows with her MTV-friendly later work; it's all one long, coherent arc to these filmmakers. Anyone interested in the early punk stuff is just going to be made sad by seeing Williams’ video for "It’s My Life" which re-imagines her as sort of a female Dee Snider, complete with a joke-y video and hollow, pseudo-subversive finger-pointing. The song itself is a fist-pumping anthem designed for greasy teenage boys to sing along to in their bedrooms while they fantasize about what it's like to have a girlfriend.* The video even cribs some wacky pro-wrestling imagery from Cyndi Lauper – hey, they're both chick rockers with crazy haircuts, right? It's also telling how the vaguely apocalyptic imagery of her lyrics transitions so easily from raw edged punk to over-produced metal; I've always thought that the defiantly immature bile of the Sex Pistols has way more in common with slickly conceived bile of The Scorpions than most music fans would care to consider. The main thing this documentary ends up proving is that it's a short jump from getting beaten up by the Milwaukee cops for your art to chumming around with Joan Rivers to promote your new album. You'll need to bring your chainsaw in either case.

* In the interests of truthfulness, I should admit that I actually really, really enjoy this song. I plan to drive along listening to it in a convertible full of explosives, to drive that convertible to the edge of a cliff and at the last second jump out of the convertible onto a ladder hanging from a low-flying bi-plane. It will be awesome. However, that doesn't change my assessment of the song's designed purpose.

3.26. No movie.

3.27. Decalogue VII: "Thou Shalt not Steal."

(dvd) my apartment.

Ok – I finally turned up one of these that I hadn't previously seen. This film revolves around a kidnapping in which the relationship between the participants is always shifting. In one of the most deft turns in the series, it deals with the ideas of familial possession, of possessing moral right – can such things be stolen? When is your daughter not your daughter? When you've abandoned her from callow self-interest? When you give her up for necessity? When she's physically snatched out from under you? Is it theft to reclaim your real daughter, one you never wanted to give up in the first place? What if you're emotionally unstable and taking her from a loving guardian? The film takes an interesting approach to constructing its narrative, evoking a fairy tale journey through the woods, an escape from a wicked witch. Many of the visuals (an abandoned carousel, for instance), filmed in warm, colorful hues atypical to the series, add to the slightly fantastic feel. Although, the film always remains firmly rooted in reality and never steps over the line into surrealism, the allusion to such stories is plain. Ultimately, this film is a clear-eyed critique of such good vs. evil world-views, the ironic and wise theme that courses throughout the series as its lifeblood.

Ok – I finally turned up one of these that I hadn't previously seen. This film revolves around a kidnapping in which the relationship between the participants is always shifting. In one of the most deft turns in the series, it deals with the ideas of familial possession, of possessing moral right – can such things be stolen? When is your daughter not your daughter? When you've abandoned her from callow self-interest? When you give her up for necessity? When she's physically snatched out from under you? Is it theft to reclaim your real daughter, one you never wanted to give up in the first place? What if you're emotionally unstable and taking her from a loving guardian? The film takes an interesting approach to constructing its narrative, evoking a fairy tale journey through the woods, an escape from a wicked witch. Many of the visuals (an abandoned carousel, for instance), filmed in warm, colorful hues atypical to the series, add to the slightly fantastic feel. Although, the film always remains firmly rooted in reality and never steps over the line into surrealism, the allusion to such stories is plain. Ultimately, this film is a clear-eyed critique of such good vs. evil world-views, the ironic and wise theme that courses throughout the series as its lifeblood.

3.28. Deaclogue VIII: "You shall not bear False Witness."

(dvd) on the train to work.

Surely the most static of the ten films, it might be attempting to additionally label this episode as the worst of Kieslowski's Decalogue. However, the film builds to a substantially emotional climax that makes it difficult to really differentiate its quality from the rest of the uniformly excellent series – it's kind of a chore to sit through, but the ending pays off enough that you don't regret it. The problem here is that, for once, Kieslowski has failed to suitably dramatize his material: the majority of the film revolves around a lecture by a college professor followed by extended conversation between that professor and a reporter – a reporter with a more meaningful connection to the lecture than she initially lets on. In short, the film has a pretty crippling case of "telling not showing." The narrative points that actually generate the big climax are discussed by the characters rather than shown in dramatic scenes. It’s essentially a spoken exchange that goes, "hey, remember when that happened?" Rejoindered by, "yes, but isn't it true that it actually happened like this?" And finally, "Not exactly – I will now verbally reveal to you how the final truth is possibly even more complicated than either of our original presentations of it."

I mean, Kieslowski's not an idiot, I’m sure he's aware of this; and this narrative format for examining "You Shall not Bear False Witness" probably has to do with the fact that it's the one commandment explicitly regulating verbal activity: bearing witness essentially relates to the words coming outta yo’ mouf. And that, I guess, reveals an underlying cleverness of the series: almost all of the other commandments suggest little narratives with clear series of actions (easy pickings for dramatization). Making ironic drama from the Ten Commandments is kind of a slam-dunk proposition in terms of getting ideas for the stories. Granted activities like "coveting" and "honoring" are really mind-crimes, but they clearly suggest real dramatic conflict. Episode VIII wisely chooses the elusiveness of truth and the human capacity for self-deception as the engine to drive its devastating ironies, but Kieslowski ultimately ends up with too much of characters awkwardly talking their way through the themes – the episode feels less like a discrete dramatic story and more like the director's subversive version of a Sunday School lesson.

3.29. In the Shadow of the Moon.

(digiBeta) JBFC.

This film is strictly PBS grade and offers absolutely no new revelations about the NASA's Apollo program that haven't already been covered extensively (and with great skill) by films such as For All Mankind and The Right Stuff. If you've even only seen Apollo 13, you're probably familiar with a lot of the material covered by this rehashing of America's efforts to put a man on the moon by the end of the 1960's. Its serious, near-reverential approach to the men involved with the Apollo program predictably smoothes out any of the jagged corners of the story and the film lacks either For All Mankind's genuine sense of the mind-altering awe that space-flight rapturously awoke in the astronauts or The Right Stuff's exhilarating journalistic flair for small, telling details and colorful, out-sized characters.

Nonetheless, space travel is pretty awesome and there are many films far less engaging than In the Shadow of the Moon. The film has some structural problems (such as its awkward attempts in the final third of the film to inter-cut the story of the first Apollo's mission to land on the lunar surface with a more general set of reminiscences about the Apollo program) and seems bizarrely insistent on using only the most bland, trite quotes from the astronauts (who frequently seem to have a pat, rehearsed act about the program). On the plus side, there's some compelling stock footage early on of space-craft tests and the whole thing moves at a quick clip. Strangely, I feel like the film featured numerous shots of waving flags and several instances of solemn patriotic hymns popping up on the soundtrack, but I can't say for certain that either of those things actually happen – that's just the kind of overall feel this film has. At the end of the movie, there's an extended montage covering how the astronauts were able to achieve world peace. So, it's good that worked out. Like I said, the movie is fine and it's a hard story to fumble. Still, you have to wonder why filmmakers would make a film about leaving the planet by employing a style as pedestrian as a walk in the park. Also, Buzz Aldrin seems like a real tool – watching him here, I was shocked that he was willing to do even a gently self-deprecating cameo on "The Simpsons." But, whatever - the man went to space. What have I done with my life?

3.30. Decalogue IX: "Thou Shalt not covet thy neighbor’s wife."

(dvd) on the train.

The heart-breaking sister episode to series-best Decalogue VI, this episode concerns an impotent middle-aged man who encourages his wife to take a lover – but with a sort of don't ask, don't tell rule. Slowly, his ego gets the better of him and when he finds out she's done just what he suggested, he's thrown into a jealous agony and vows suicide. The narrative twists one final time with the revelation that she was already breaking off the affair before he discovered it. Again, the plot's ironies are so simple and true that it seems almost pointless to discuss them at length. It's a film that wields the blunt, deadening weight of impossible desire against a shatteringly sympathetic portrayal of all its characters. At its core is the most fundamental of human agonies: this world will never be exactly as we desire it to be. It follows the poisonous moral rot that leaks from an irresolvable frustration: the choice of the couple is to settle into sexless misery or tear their relationship apart. Our inability to control and mediate our emotions is the intertwined torment: if he could prevent himself from being jealous, if he could just somehow feel otherwise, there would be no problem. But just as "Ivan believes or he does not believe, but he cannot choose," the main character of IX stands before his wife sick with jealousy. He cannot do otherwise. Amen.

The heart-breaking sister episode to series-best Decalogue VI, this episode concerns an impotent middle-aged man who encourages his wife to take a lover – but with a sort of don't ask, don't tell rule. Slowly, his ego gets the better of him and when he finds out she's done just what he suggested, he's thrown into a jealous agony and vows suicide. The narrative twists one final time with the revelation that she was already breaking off the affair before he discovered it. Again, the plot's ironies are so simple and true that it seems almost pointless to discuss them at length. It's a film that wields the blunt, deadening weight of impossible desire against a shatteringly sympathetic portrayal of all its characters. At its core is the most fundamental of human agonies: this world will never be exactly as we desire it to be. It follows the poisonous moral rot that leaks from an irresolvable frustration: the choice of the couple is to settle into sexless misery or tear their relationship apart. Our inability to control and mediate our emotions is the intertwined torment: if he could prevent himself from being jealous, if he could just somehow feel otherwise, there would be no problem. But just as "Ivan believes or he does not believe, but he cannot choose," the main character of IX stands before his wife sick with jealousy. He cannot do otherwise. Amen.

3.31. Decalogue X: "Thou Shalt not covet they neighbor's house."

(dvd) on the bus to Philadelphia.

For some reason, this episode is always described as being "a black comedy." The first time I read that, I thought back over the film and scratched my head – did I just not get it? Granted the heavy metal band stuff is fairly incongruous to the rest of the series, but I'm not convinced that in this case incongruity = comedy. The plot (two brothers unexpectedly inherent a valuable stamp collection, but in order to cash in they need to get back a single stamp that they accidentally gave away) in some ways has less at stake than any of the other films, so I guess that makes somehow makes it more amenable to humor but I still just don’t think this is funny. Certainly, this is one of the least ironic films in the series and one of the few times that the commandment seems like little more than a opporunity for the characters to learn a moral lesson in a straight-forward fashion.

Kieslowski regular Jerzy Stuhr is great as the brains behind the operation, but I found the other brother to be one of the weakest performances in any of the ten films. Certainly, the general lack of irony means that there's less to disentangle than usual with the Decalogues, but the tight plotting makes it probably the most straight-up entertaining film in the bunch. And that's really the strength and weakness of this final film: it gives itself over to following a well-crafted, suspenseful little thriller without ever seeming to have too much on its mind beyond the dramatic tensions that are easily mined from petty greed and half-baked planning. It's definitely the only time I've ever thought to seriously compare Kieslowski to Hitchcock and that includes Decalogue VI, which definitely has some surface similarities to Rear Window. I guess that this film could be taken as an after-dinner mint, designed to cleanse your palette of the complex tastes of the earlier films and afford you a less jarring re-acquaintance with comparatively bland tastes of most cinema.

home about contact us featured writings years in review film productions

All rights reserved The Pink Smoke © 2010