~ by john b. cribbs ~

Around this time of the year (y'know, Christmas time) I always get to wondering: how do all the same mediocre movies end up on everybody's year-end "Best" lists? I'm not going to single anything out - you movies know who you are - and really my frustration towards titles whose positive critical moss gathers as their releases roll towards award season isn't really hateful in any way. I just can't help thinking about the specific point where the spark ignites which leads to any given hit film achieving box office triumph and unanimous praise. It's happened too many times that I'll walk out of a movie totally floored, giddy even, my passion for the art of film rejuvenated through the pure brilliance of what I've just seen and heard, and I'm invigorated by the anticipation of said brilliance moving from one theater to the next, infecting one viewer after another, until said movie is canonized as a modern classic...only to have that final step never transpire. Too many great films have fallen into instant near-obscurity while the Slumdog Millionaires of the world have soared to accordant public approval. It always seems like such a befuddling and random process, but then I'm the guy who once rolled his eyes at an teaser poster for Shrek and confidently proclaimed, "That's not makin' any money."*

As someone with a tenuous grip on the lowest rung of success and a tendency to dwell on vague insecurities as to my own self-worth, I'm naturally obsessed with what bolsters filmmakers and their work to the heights of universal acceptance. Like how much success is attributable to reputation: if all the right critics rave about Gravity and supply it enough illustrious gravitas to push it above the 95% line on Rotten Tomatoes, does that mean you're incorrect to disagree?** If 50,000,000 IMDb users can't be wrong, than The Shawshank Redemption must be the greatest film ever made, right? Is Pulp Fiction genuinely the most important film of my generation just because many people claim it to be so? On the flip side, does that mean a movie or director who's been widely condemned or virtually ignored is truly worthless? I'm just applying this to cinema, but am equally beguiled by the lucrative climb of high scorers in any area, be it business, politics, literature or just general popularity - how many acknowledgements of worth did it take for them to cement a durable stake in their given field? And what percentage was earned by sheer fortitude as opposed to flimsy luck?

Preston Sturges' own bridge to fame was braced between an auspicious convergence of irrefutable talent and good timing. Despite three Broadway flops in a row, he received a record sum for the film rights to his play Strictly Dishonorable. After that, he was offered a then-unprecedented deal that scored him a percentage of the film's profits for his first script, The Power and the Glory. Accepting practically no money for a chance to helm his successful directorial debut The Great McGinty, Sturges ended up with the first-ever Academy Award for Original Screenplay and found himself on course to make seven consecutive bonefide masterpieces, comprising one of the most seamless directing streaks in film history. No doubt recognizing this winning combination of avid gusto and serendipitous fate, Sturges applied the same his characters. Whether it be derelict Dan McGinty effortlessly whisked into gubernatorial prestige or a resilient Gerry Jeffers running off to Florida to net a rich husband after being miraculously bankrolled by the Wienie King, several Sturges heroes find themselves unexpectedly visited by sudden and superficial success. While rags-to-riches scenarios (best exemplified in the excellent Sturges-written Easy Living) weren't uncommon in screwball comedies, Sturges quickly spurned the kind of fairy tale formula he'd already sent up in his screenplay for The Good Fairy in favor of a more critical view of quick, easy happiness. While conceding that unbelievable luck and crazy circumstances factor into that chance, his characters' true virtues are revealed when they derail the vertiginous rush of incidental prosperity, epitomized in such distinguishing moments as McGinty's "one crazy minute" of honesty and Gerry rejecting life as a millionaire for an uncertain future with destitute hubby Tom. Even Sturges' more specifically Christmas-set/themed script Remember the Night, which was allegedly softened up by director Mitchell Leisen, is resolved with the unlikely redemption through a mutual exchange of honest and dishonest principles between the two leads.

More innately virtuous though not quite as resolute as a McGinty is average New Yorker-turned-King for a Day Jimmy MacDonald, the hero of Christmas in July, Sturges' second film which the director adapted from his unproduced play A Cup of Coffee (which had served as the calling card that caught Hollywood's attention and scored him his first string of screenwriting gigs). Jimmy, along with millions of other hopefuls, has submitted a slogan to the Maxford House Coffee jingle contest in hopes of having his entry become the company's new tagline and winning $25,000. His fiance Betty, who also works at an entry position at the same (rival) coffee company as Jimmy, indulges his enthusiasm for his hilariously backwards slogan - "If you can't sleep at night, it isn't the coffee, it's the bunk!" - while remaining skeptical of its chances of actually winning the competition. The contest itself is at a stand-still due to a deadlock between 11 jury members and adamant hold-out Bildocker (played to ornery perfection by that most reliable of Sturges stable character actors William Demarest), much to the frustration of company head Dr. Maxford who just wants the whole thing over and done with: "What good are these contests anyway? They interrupt the entire organization, they make ya millions of enemies, and all they prove is you're making too much money in the first place, since you can afford to toss a large chunk to some sap head who probably never had a cup of your coffee in his life but lives on goat's milk!"

Taking advantage of Jimmy's excitement during the jury's deliberation, a trio of co-workers, all prank call enthusiasts, doctor up a phony telegram informing Jimmy that his slogan has won. Jimmy has an explosively overjoyed reaction to the news and, to the pranksters' shared horror, things escalate quickly: the big boss, Mr. Baxter, is so impressed by Jimmy's win that he promotes him and orders his think team to get cracking on the multiple inspirations his new protégé has to offer the company. Ensuingly, a series of assumptions and misunderstandings lead to Jimmy being awarded the check and blowing a large amount of it on an engagement ring for Betty, household items for his saintly mother including "irons that do everything but sing," and presents for everyone on the block.

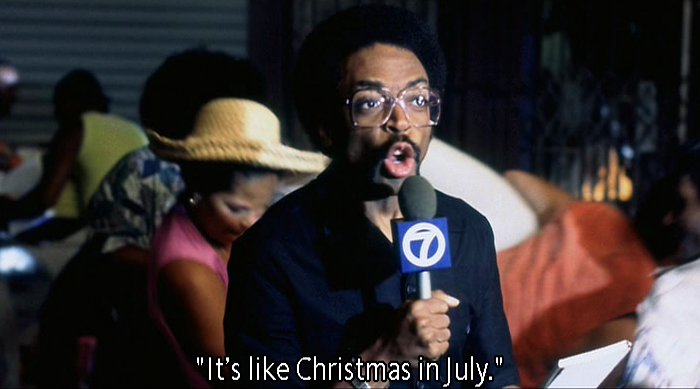

It's this section of the film that best justifies the title: Jimmy and Betty indiscriminately handing out gift-wrapped packages to all the kids, Dr. Maxford and the department store managers, who've discovered the mistake, showing up like a pair of Scrooges to attempt and pry presents out of children's hands, the whole neighborhood brought together in unity and celebration like the town at the end of It's a Wonderful Life (just to iterate that it's not religious, Sturges adds an Orthodox Jewish couple to the tenement gang). By all counts, this moment is the movie's "Christmas in July" (the phrase originates from an opera based on Goethe's The Sorrows of Young Werther; the film was originally titled simply The New Yorkers). But since Sturges is always more interested in the humorous plight of individuals rather than communities or the Fordian "common America" - a sense of guilt over this very thing preoccupies Sturges surrogate John L. Sullivan - the Christmas in July most likely refers to Jimmy's surprise "win." It's easy to assign roles based on that: goofy old Dr. Maxford as Santa Claus, the members of the jury his 12 chain-smoking reindeer in shirt sleeves...and hey, the three jokers who play the prank (kind of lazily named Tom, Dick and Harry) who unwittingly bestow Jimmy with lavish riches are kind of like the Three Wise Men, right? Betty actually opines "It's like Christmas in July!" while sitting in the back of a luxury car following their dizzing shopping spree before the couple arrive to rain gifts on the neighborhood: good fortune, widespread as it grows, has come to Jimmy first and foremost. Rising to the top so abruptly has brought him the kind of hope promised by the end of any given year: "Everything new, clean - different!"

Of course, Betty's analogy should have warned Jimmy as to the fraudulence of his good fortune: Christmas doesn't come in July, anymore than a man is made by a hit catchphrase and a big check. Struges likes Jimmy, whose father, it's mentioned, invented a car where wind is scooped up in front and pushed out of the back to make it go (Sturges was an inventor himself and even had a hand in creating the Davenola, the multi-functional davenport with materializing ice box and telephone seen in the movie). If Frank Moran, the gruff character actor who appeared in ten consecutive films by the director (usually uncredited) vouches for a guy, as his patrolman does here for Jimmy, you know Sturges likes him. He doesn't fault Jimmy for getting swept away by what turns out to be a sobering 15 minutes of fame, being aware firsthand just how intoxicating instant success can be, and how infectious. If a man is nationally recognized as a genius, than those around him assume it must be so. If he's carrying a check for $25,000 then he must be worth $25,000 (or roughly $400,000 today).

These are the erroneous expectations that open every door for Jimmy in the brief time before the truth is revealed, and the real disappointment once those doors are slammed shut is that Jimmy's estimation of his own worth has been decimated along with everyone else's. It humbles an already unassuming small figure, but it doesn't destroy him: Sturges' portrayal of a heartless, uncaring corporation is still a lot softer than what you'd find in a Frank Capra movie. Sturges regular Raymond Walburn, later given a similar role as the mayor in Hail the Conquering Hero who first hails then sets out to ruin Eddie Bracken's returning "hero," beautifully plays Dr. Maxford as just one second behind everything that's going on, like he's so focused on being successful he's forgotten how to deal with other people. Much like Frank Morgan and Edward Arnold's befuddled benefactors in The Good Fairy and Easy Living,*** Walburn's unwitting fairy godfather seems more terrified of people finding out his company is "making too much money in the first place" than actually being swindled for the 25 grand; for Sturges, the distribution of wealth is as erratic and irrational as randomly winning a contest, with foolish Maxford having no more a claim to the money that's arbitrarily brought in by his company than Jimmy or his friends and neighbors. Hence the scenario's social approximation to Christmas: a time when good fortune is wished upon and distributed to everyone from muddled moguls to desk clerks.

One of the best scenes of the film involves Harry Hayden's hopeless office manager at Jimmy's company, a middle man so profoundly mild mannered I can't even remember the character's name. As he glances around the silent office, casting a disapproving look at Betty when she arrives a few seconds late at her desk, you think Sturges is introducing an inherently hissible staunch bureaucrat. So it comes as a surprise that Hayden's character is not really a bad guy and has in fact developed the ultimate crepehanger maxim for himself, a defensive indifference built up against the universe's random assignments. He tells Jimmy: "Ambition is all right if it works, but no system could be right if only half of one percent is successful and the rest of us all failures. So I'm not a failure, I'm a success." He tells this to Jimmy to prepare him for the blow of not winning a contest where the odds are one-in-a-million, and from that stance his advice is absolutely sound: it just doesn't work out for some people. Sturges had that one-in-a-million talent and therefore rose to the ranks of Hollywood filmmaker, but modestly suggests that the compromises of people like Hayden's character isn't necessarily the defeated death rattle of losers...just that it need not apply to everybody. Immediately after their talk, when Jimmy jumps on top of his desk to announce his "win," Hayden is absolutely thrilled for him and even puts himself on the line to sort out the confusion when their irate boss comes around ready to fire everybody for the disruption of work; you like to think that after this experience he'll never dish out his little piece of pessimistic wisdom to an employee again.

What Hayden miscalculated in his screed is that feeling successful isn't the same as feeling important. When he picks up his check, Jimmy tells Maxford the real delight of winning the contest isn't that he can buy his poor mother a fancy davenport, but that "I thought up a better slogan than anyone." It changes his impression of himself and what he has to offer to the universe. A sense of sudden self-worth could also be said to inform the obstinance of William Demarest's Bildocker, the Henry Fonda of his 12 man jury: when Dr. Maxford thinks the contest is over and orders everyone back to work, you can't help but remember an earlier mention that Bildocker works for the shipping department. A deadlocked jury would keep him out of this unglamorous position - while I don't doubt Bildocker's integrity over finding the best slogan, I'm sure the idea of keeping millions of radio listeners in suspense and making the boss look foolish are tempting enough reasons to hold out as long as he can. He even has the audacity to tell Maxford to his face: "You can fire me out of the shipping department but you aren't going to fire me off this jury because I don't work for you on this jury!" Just as "winning" the contest has given Jimmy the confidence to start pitching his private ideas to his boss, being a part of this jury emboldens Bildocker to emasculate his.

On the other hand, the falseness of instant success is why, despite the fact that July is incredibly funny and charming from beginning to end, there's a tinge of sadness running throughout. Maybe that's because, like Christmas, Jimmy's promotion and Bildocker's power as head juror merely temporary - how bummed does the average American feel when he has to go back to work and pay off that credit card bill after the holidays are over? It's not that Sturges believes a lottery winner doesn't deserve his instant success, or the right to be heard just because he came up with a catchy slogan - only that a dangerous quantification of lucky breaks over genuine effort can't sustain itself. As the janitor at Jimmy's job tells him, you can't predict what a black cat one's crossing path portends - it depends on what happens afterward. The door swings both ways: just as quickly as being blindly judged a winner, one can be blindly dismissed as a loser. Sturges doesn't really subscribe to a cynicism about life for lower middle class Americans, but by warning of the downside to instant success he avoids that kind of rosy Hollywood sentimentality that prevailed in many a forgotten film from that era. Even when Jimmy is at the height of his giddiness, pitching to his boss the idea of Blueblood Coffee - "It's bred in the bean!" (note: not bread in the bean) - one executive deems the slogan "money in the cup," oblivious to the fact that he's just made a visual comparison to a beggar on the street. Dizzing highs and crushing lows are separated only by a pretense of stature.

"You can't lose anything you never had," Betty reassures Jimmy after he's learned the truth, seemingly missing the full implication of the innocent reassurance: that what he never had was talent, or hope of success. The same sad reality comes early in Sturges' The Sin of Harold Diddlebock, in which Harold Lloyd's title character is offered a great job by big company CEO J.B. Waggleberry based on his (accidental) great performance in a college football game only to be fired after years of merely adequate productivity, having misplaced the moxie that got him noticed in the first place. Diddlebock manages to find second life through an even more unbelievable twist of erratic circumstances beyond his intentions, essentially while the former teetotaller is inebriated by a magic pixie drink of Harold's (again, accidental) concoction. I think one of the reasons Diddlebock ultimately fails as a movie is that it's about falling unwittingly into good fortune despite overwhelming hardships rather than reality settling in after events transpire that are apparently going to make things ok from here on out.**** The difference between Harold's magic drink and Jimmy's magic ticket of a phony telegram is that potential needs to come from true inspiration, and Sturges obviously feels more fondness for a hilariously non-sensical catchphrase than a fairy tale elixir that turns a man into an inadvertent success.

Jimmy's boss Mr. Baxter, like Mr. Waggleberry, has no eye for true talent but is impressed by all the flash and promotes Jimmy based on impression alone, only to strip it away when the confidence turns out to have been unfounded. Jimmy accepts his abrupt fall as instantly (if not quite as enthusiastically) as his sudden victory: he's the prototype for the bashful Eddie Bracken character found in The Miracle of Morgan's Creek and Hail the Conquering Hero, an honest yet utterly unconfident schlub who's just happy to get attention from others that he doesn't believe he merits. While this might make Jimmy a less interesting hero than Struges characters who actively change their ways despite being unabashedly corrupt (McGinty), dishonest (Jean Harrington), manipulative (Trudy Kockenlocker) or pretentious (John L. Sullivan), like Bracken's leading men Sturges admires his indefatigability. "It's still the same idea, isn't it?" Jimmy meekly inquires before confessing to Baxter about not actually winning the contest as the boss recites his Blueblood Coffee pitch, making a case that's as consoling to himself as it is convincing to Baxter. The great thing about Christmas in July is, whether Jimmy really does have the tools to be successful and make other people more successful is left entirely ambiguous. Declaring someone a success is no more plausible than the claim that coffee makes you sleep - it's not a common thing that's easy to recognize as incontrovertibly true, but there's always the possibility, one out of a million times, to be absolute fact. So although Betty actually drops the title into the dialogue, Jimmy's mother hits the sentiment more accurately on the head when she surrenders to the logic of her son's slogan by acceding that "water runs uphill, and dogs meow and cats bark, and water's hot in the wintertime and freezes in the summertime." Mixing up summer and winter: Christmas in July!

Jimmy's such a charming winner and gracious loser that Sturges can't help but sneak in a last minute total victory by revealing that Jimmy's slogan has been the winning entry Bildocker's been defending all along. This could be seen as refuting everything he's put forth about the pitfalls of instant success, but I'm willing to let it slide. Maxford and the department store heads go from thinking the best of Jimmy to the worst, that he's a crafty con artist and a thief, and the only way to make them look more foolish than believing Jimmy's ideas were worthwhile is to have them reject him and turn out to be wrong. Besides it's not a total Hollywood sellout ending: Sturges leaves his young couple in an ambiguous state. They don't know about Bildocker's decision and are last seen descending the company elevator to an uncertain future - the director has given the audience their happy ending while denying his characters. Jimmy and Betty end up in the same place we first see them, together at the top of a building getting by on dreams, only with the added bonus of Mr. Baxter agreeing to give Jimmy a probationary period in his new assignment based on Betty's argument that he "belongs in here because he thinks he has ideas." For Sturges, the ability to see the potential in himself without outside assurance is the best way to see beyond the money in the cup. And anyway, it's good to know there's always a Bildocker out there who appreciates a phenomenal pun, even if it doesn't make a lick of sense.

July is considered minor Sturges in most circles, and I guess I can see why. It takes place over one day, almost like a Preston Sturges short story (it runs just over an hour) than a sprawling novel like Sullivan's Travels or The Palm Beach Story. It might seem tame compared to some of his later, more risque movies (he does get away with the ol' cut-to-rabbits-when-lovers-say-goodnight shot) and the couple may be a little too wholesome compared to Fonda/Stanwyck or McCrea/Colbert. Ellen Drew, in an admittedly thankless role that's a step down from Muriel Angelus' headstrong single mom from McGinty and miles away from Barbara Stanwyck's dominating Jean Harrington in The Lady Eve, executes the worst-looking pratfall from any of Sturges' films (the existing clip feels like a "forget it, let's move on" take that couldn't be cut later due to continuity). For his part Dick Powell - more famous before as a crooner and after as a film noir mainstay - does a credible job, but if Jimmy MacDonald had been played by Eddie Bracken I think July would be acknowledged as the classic that it is. But what do I know: someone on The Simpsons (I'm guessing it was John Swartzwelder, a huge Sturges fan) referenced an exchange between Powell and Drew in the very first season of the show. Moreso, confessed cinéaste Spike Lee gave a little nod to Sturges in Summer of Sam:

Struges also knows how to depower his villains by casting familiar actors: Walburn always plays the flustered crank in his movies so the viewer never expects any really searing aggression him. (Likewise, I'd say Frank Morgan's reputation as the harmless - yet vaguely pedophiliac - Wizard of Oz makes him perfect for The Good Fairy, and Edward Arnold's more villanous turn in movies like Mr. Smith Goes to Washington beautifully contrasts his good natured businessmen in Diamond Jim and Easy Living... except those movies came after the actor's performances in the Sturges written films so that application only really works retroactively. God, I hope nobody actually reads these footnotes.)