MOVIE SHELF: COMPARING FILMS TO THEIR LITERARY COUNTERPARTS

christopher funderburg

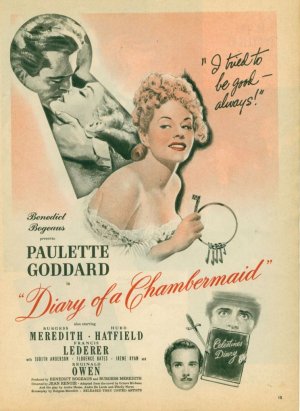

JEAN RENOIR'S DIARY OF A CHAMBERMAID

based on LE JOURNAL D'UNE FEMME DE CHAMBRE by OCTAVE MIRBEAU

page 2

"They're conservatives and I'm a liberal!"

Screenplay by Burgess Meredith! Produced by Burgess Meredith! You know it's going to be good because in his memoir So Far So Good, he misspells the man's name as "Mirabeau" and misidentifies him as "the playwright" who wrote the source work. Seriously, we need to get this out of the way: Rocky's trainer, the Penguin himself, plays a huge hand in this begotched adaptation - he even takes on the role of Captain Mauger. Sure, he eats a few flowers, but sadly when he kills his beloved pet (for some reason now a squirrel) it's purely a poorly filmed, blocked and acted accident, not an intentional act of rodent homicide. The heart of the weasel-killing scene is lost. Burgess and his wife Paulette Godard, who plays Célestine, met Renoir while working on some U.S. propaganda films during WWII and this woeful adaptation somehow resulted in that meeting.

While I wrote that I could understand what attracted Renoir to the book, I can also admit that there's a lot in there that I can't imagine was palatable to him. His films have always been so decent and modest. Even La Chienne, a story about a ruinous prostitute, is an almost totally sexless affair. His romances are chaste even when they're adulterous - whatever the opposite of an erotic filmmaker is, Renoir is that. He's also not capable of cruelty and he's generous and forgiving by nature: he's moral, if not a moralist per se. So the chance of Célestine as a character surviving intact were slim and, indeed mon freres, Mirbeau's Célestine does not make an appearance in Renoir's film.

The opening scene immediately establishes Célestine as a good and noble woman: Joseph shows up at the train station to pick up Célestine and a scullery maid, gives the scullery maid a once over and says "scram." The woman protests that she was promised a job and has no money to take the train back to Paris. Célestine gives him the ol' "now, you listen, bub, you give this woman the job she was promised or I'm walking, too!" And it works. Because she's got moxy, this one. The scene is so, so shitty. I'm not sure how quickly you can reasonably decisively say a movie stinks, but this scene is an argument in favor of "instantly." Needless to say, Mirbeau's Célestine wasn't up for such selfless interventions and would more likely think horrible thoughts about the ugly people of the world than to stand up for them. By contrast, Renoir's Célestine is savvy, know-it-all-ish - in the second scene of the film, she demands a second bed for the scullery maid after she's informed the maid will be sleeping on the floor of their bedroom. And again her demand is met without resistance. The life of chambermaid seems pretty sweet: you bark orders at your masters and their valet and get everything you want.

The Meredith/Renoir script does keep a fair amount of dialog from the book, but in such a way that warps the meaning. For example, when Mirbeau's Célestine says "Life is life," it's a weird existential plaintive. Renoir's version sees it as an upbeat inspirational message. Other times, the lines simply don't ring true when they're imported directly from the book. In the film, "They've always hurt me so now I'm going to use them! No more love for Célestine!" feels as phony as a three dollar bill with Rondo Hatton's picture on it - the film's Célestine has too much can-do spirit and optimism for those lines to have any weight. You never get any sense that she's being crushed by her menial position in life nor her desires being exploited by the powerful people around her; and why should you get that sense? She's spending all her time demanding new beds and telling people off.

More egregiously, she's deeply insulted by Joseph's cafe idea. There's zero chance of her coming along with him and the idea that she might fall for an Anti-Semitic goon like Joseph just isn't in the same universe as Renoir's take on the character. Joseph (played by Eastern European matinee idol Francis Lederer) is filmed like he's Bela Lugosi or something; he's always in looming dark shadows, his features distorted by harsh lighting, his thick accent played for maximum creepiness. Now Joseph's the monster in a creature feature - a mob of incensed townspeople even tear him to shreds at the end, although without the ironic sense of tragedy afforded Frankenstein's monster. Célestine is noble, virtuous, the anti-Joseph, his insistence "Our souls are alike" laughably absurd. She's not the character from the book.

The film is not the book - it's one of those classic manhandled adaptations where Hollywood phonies come in, steal a few lines and characters and situations and leave out the soul of the source material. Which is not to say Renoir is a Hollywood phony, but this thing has all the hallmarks of a piece taken on by hacks who didn't really care about the novel who then fart out a pointless script that was then endlessly rewritten to fit the Hayes code. It also might be unfair to totally let Renoir escape any blame - Renoir wrote the initial draft of the screenplay working from Andre de Lorde's play and it's hard to believe he couldn't have made something that works within all of the commercial and moral restrictions placed on the film that nevertheless has something of the spirit of the novel.

The final script invents a lot and twists the plot around, but also composites a few characters into a single entity. The beautiful consumptive (perversely) gets combined with the asshole son of the ecclesiastical conman* and transformed into the the Lanlaire's son (a character that does not exist in the novel). Renoir's biggest changes concern Joseph - almost all of the plot that touches him gets altered. First off, the subplot involving a little girl who gets raped and murdered (presumably by Joseph, but left ambiguous) gets dropped from the story entirely. Next, instead of successfully stealing the Lanlaire's extensive collection of expensive silver (and their antique cruet) and using his ill-gotten gains to buy the cafe in Cherbourg, Joseph's plans are sussed out by Madame Lanlaire and foiled. From there, he attempts to rob Captain Mauger and kills him in the process. That murder gets discovered and he gets chased into town and falls victim to mob justice (the best kind of justice!) during a quaint village Independence Day celebration, none of which happens in the novel.

Things like a quaint village celebration and a village wishing tree that according to local lore grants wishers true love if they sit under it with their honey-pie and wish hard enough are the kind of romanticism of provinciality that definitely would have made Mirbeau puke. No word on whether Renoir would be willing to eat that puke as proof of his love. Beyond narrative alterations, Renoir's film makes symbols even more pointedly symbolic and then spells it out, like this reference to the silver: "It represents to me as it does to you, my new position in life, my new security." Or how about ol' Captain Mauger explaining why he doesn't get along with the Lanlaires? "They're conservatives and I'm a liberal!" There's so much goofball horseshit in this movie - I think Renoir wants it to be a bit of manic farce, but it just never plays for even one second. I hope he wasn't aiming for something subtle like Rules of the Game. That would be sad - this is a movie where characters cackle and whimper and dance around all goofy-like and talk in exaggerated "funny" voices.

A few examples: the climactic greenhouse fistfight between Joseph and the newly-minted Lanlaire boy is so ridiculous. I honestly can't tell if it is supposed to be funny or just so poorly choreographed and executed as to be silly. I mean, Joseph is a murderer - this shouldn't be a joke, right? Anyhoo, I am sure you will be delighted to hear that not one, but two simpering halfwits have been added to the story: the ridiculous scullery maid and a monosyllabic, beloved village idiot. I won't spoil it for you if they fall in love or not - I'll let you experience that magic for yourself. And I'll say this about another key performance: it's a total toss-up if Burgess Meredith's take on the Captain or his portrayal of Oswald Cobblepot is more of a hyperactive cartoon.

One minor point before I move on from simply working through this endless list of everything the movie botches - it might seem like a small thing, but it's indicative of everything the movies gets wrong. In the novel, the jerk son of the ecclesiastical conman thinks he knows everything there is to know, he's bored with almost every topic and when he talks to Célestine he has a phrase that he repeats to indicate "yeah, I've thought about that, I'm done with that boring nonsense because I am a know-it-all." My version of the novel translates the phrase as "I have 'supped' on it," but it is clearly an idiom that defies easy translation. For some inexplicable reason, Meredith's script includes this totally extraneous verbal tic but awkwardly translates it as "I have 'had' it." The actors lean into the "had" to make it as awkward as possible - just a perfect example of the film getting the letter but not the spirit. That the script gives these lines to the consumptive/Lanlaire's son makes even less sense.

Most egregiously, Renoir's film does nothing to clarify for me what a cruet is. The film seems to indicate it is some kind of a big cabinet/credenza, but wikipedia insists it is a "small flat-bottomed vessel with a narrow neck." What differentiates it from a carafe, is that it has a "pheodelia." Way to drop the ball on that one, Jean.

Seriously, though, this film is most notable for what a baffling betrayal of Mirbeau's book it is. In Renoir's phonytown ending, Célestine marries the consumptive Lanlaire son who has miraculously overcome his illness. (It is implied that Proletariat Power! is what did it.) On their honeymoon train-ride, he encourages Célestine to write a final entry in her diary, which she does: "Forsaking all others, through sickness and health, for better or worse, till death do us part." Mirbeau's version of Célestine's final entry, as she joins child-rapin' Joseph to become a cafe-whore in Cherbourg: "Really I am powerless against Joseph's will. In spite of this fit of revolt, Joseph holds me, possesses me, like a demon. And I am happy in being his, I feel that I shall do whatever he wishes me to do, and that I shall go wherever he tells me to go...even to crime!" The endings are literal opposites.

Renoir's film is at its core a leftist fantasy of Mirbeau's truths: both artists despise the vicious Anti-Semitic rightwing Catholic hypocrites of France and both men seek to create an artwork to attack or at least undermine those forces, but Mirbeau offers an honest assessment of the source and influence of those rightwing impulses (including the inability of likable working class folks like Célestine to resist those forces) while Renoir offers an uplifting tale of overcoming that cultural malignancy. In Renoir's film, the stolen silver is given away to the crowd of townsfolk, the cowed Monsieur Lanlaire defies his shrewish wife and throws open the shutters in support of Democracy to let in the voice of the townspeople singing, the Captain claims his liberalism as the origin for his Lanlaire-antipathy,** the reactionary Joseph becomes the monstrous villain bested collectively by the good-hearted townspeople, Célestine the servant becomes decent and hard-working (even heroic), the consumptive Lanlaire son declares after his bout with Joseph "The more I'm beaten, the stronger I become!"

This is all purely Leftist fantasyland stuff, an impression only enhanced by its fake-y sets and cartoonish performances. But coming right on the heels of France's liberation and Fascism getting its ass kicked up and down the block, the street, the ave, whatever, I can cut Renoir a break for embracing a corny, dubious Leftist optimism. Incidentally, I'm fascinated by the lengths critics will go to defend a work, any work, by a beloved filmmaker. I found countless reviews online that referred to this film as "dreamlike" or "possessing a dream logic" or some variation on how its stiltedness and artificiality is somehow intentional. There's no reason to defend a movie like this. Renoir made tons of good ones - it's alright to focus on those and toss this one out like so much trash. He's got not only Rules of the Game and Grand Illusion, but lesser known films that actually do deserve critical praise and to be highlighted and rediscovered like The Crime of Monsieur Lange and La Chienne. Renoir himself thought of Diary as a failure, so at least somebody around here gets it, man.

Beyond latter-day praise, it was named one of the 10 Best Films of 1946 by the National Board of Review, which is actually a pretty good list*** apart from Diary and Jacques Becker's awful Goupi Mains Rogue, another punishingly unfunny manic comedy set in provincial France. I actually thought of Goupi when I was watching Diary - I wanted to mention the connection because they're so similar (and similarly bad films from legendary filmmakers). Anyhoo, if the National Board liked one, it makes sense that they liked the other. Another incidental: Becker was Renoir's former assistant director. And Renoir hated Goupi. Which I guess is also consistent: it makes sense if he thought his own film was bad that he disliked the other. Buńuel claimed to have never seen the Renoir film, which was the right call for a number of reasons. In fact, he made every right call when it came to Diary and created a film that I think surpasses even the novel.

* This character's section of the novel is pretty great/infuriating. He seduces Célestine and is so good in bed she becomes obsessed with him. His family isn't actually as financially stable as they appear to be, so he starts doing things like asking her to loan him money which he never pays back. But once he's bored of her, he gives her money after sex. Ouch. For her part, Célestine tries to play the perverted, adulterous father off of the son to her advantage in both directions, but gets totally humiliated.

** In the book, he's a childish jerk who delights in throwing his trash in their yard, shattering their greenhouse windows, killing their cats and cutting down their trees just for the hell of it. If there's a motivation for his behavior, it's insignificant and definitely not an act of political defiance.

*** The list includes Open City, Brief Encounter, My Darling Clementine and Robert Siodmak's The Killers. Also, I have seen the list credited in several places as the "Best English Language Films" which (if true) makes it baffling that Open City and Goupi are in there. A Walk in the Sun also turns up on the list, making 1946 a banner year for Burgess Meredith, who had a hand in getting that film made (he narrates it as well). A Walk in the Sun is also terrible.

<<Previous Page 1 2 3 Next Page>>

home about contact us featured writings years in review film productions

All rights reserved The Pink Smoke © 2013