THE FiLMS of

MARK L. LESTER

eric pfriender

Happy Thanksgiving, everyone! Today we focus on a movie most people consider a turkey.

Add this to Funderburg's thoughts on Lady Jayne: Killer and you might question whether this series should actually be titled "Mark L. Lester - weak!"

But honestly, in a 40 year/30 film career you're not going to please everybody all the time. Although certain moviegoers (myself included) have found things to love about today's movie, it admittedly has more detractors than supporters. So as Lester lights the 65th candle on his birthday cake this weekend (get it? fire) we check in with today's guest writer to see whether the film will be redeemed, or go up in flames...

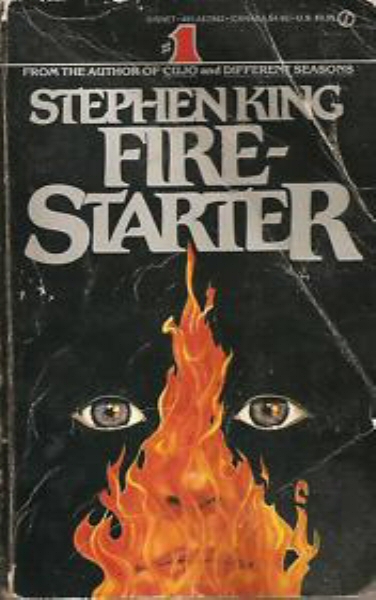

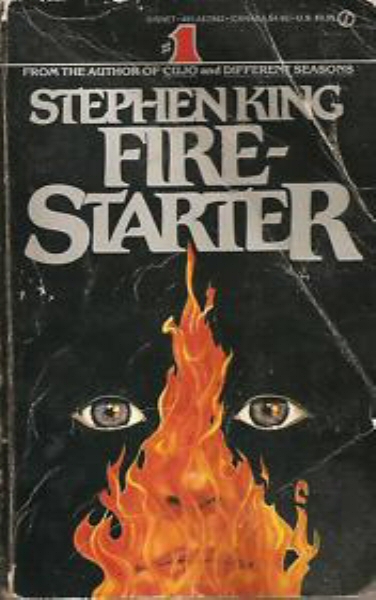

FIRESTARTER

mark l. lester, 1984.

I discovered Stephen King at church.

I'm not religious now and, truth be told, I wasn't religious then. But I had parents who, in addition to being genuinely good parents, were also "good" parents. And part of being "good" parents meant that you did the right thing and you brought your kids to church. Once we settled into Hillsborough, New Jersey, which was the town I grew up in, they found a nice Lutheran Church whose congregation was small but growing, and

every Sunday until I became enough of a teenager to flex my contrarian muscles and refuse, we went to church and Sunday school.

The church was relatively small. A modest, brightly-lit sanctuary, a few classrooms and offices, and a main lobby area. Here, after each service, the congregation would, um, congregate. We would shake hands with Pastor Walt, loosen ties, and occasionally contribute to one of the humble fundraisers such as the occasional bake sale, or the even rarer book sale. Now anyone who knows me at all knows I’m powerless to resist a book store, book sale

or book shelf. (Ask my wife where to find me if we pull over to hit a thrift store: sitting in a beat-up chair in the book corner, twenty pages into some shitty Crichton novel - that’s where.) And it was at one of these book sales, when I was about 12, that I first saw the cover of Stephen King’s Firestarter.

I judge books by their covers. (So do you, film nerds. Which of you hasn’t bought the Criterion edition of something you already owned because the package design was too damn good? You know who you are.) This particular paperback edition drew me in. I had a budding teenager's mild pyromania, but other than that there was nothing about the book itself that would cause me to become fascinated. For whatever reason, I was compelled to reach out

and grab it. I ended up dropping 2 bucks that day and bought Firestarter, Pet Sematary and The Bachman Books. Teenage Eric thought The Long Walk from Bachman was brilliant, and I still stand by Pet Sematary as being the only genuinely scary book I've ever read,* but Firestarter is still my favorite King novel.

Firestarter contains the following things: genetic mutations, psychedelic drugs, psychic powers (including - but not limited to - pyrokinesis, telepathy, telekinesis and something King terms 'mental domination' that I wish I had), shadowy government conspiracies involving organizations more secret and shady than the CIA, and lots of violence.** This list pretty much explains why I loved the book as a teenager, and why I love it still.

The book opens with Andy McGee on the run with his 8 year-old daughter, Charlie. At first we're not sure why they're running or who they're running from. Through a series of flashbacks we find that the men chasing them are agents of The Shop, a shadowy government organization interested in paranormal phenomena. Years earlier, back in college, Andy had participated in a Shop-sponsored psychological experiment in which the participants were

administered a low-level hallucinogen known as Lot-6, which was hoped to induce and heighten various psychic powers in the participants. The experiment was a success in the sense that all of the participants exhibited the anticipated abilities; a disaster in the sense that several of the students were either killed or maimed during the experiment. Years later, participants are dropping like flies, driven mad and committing suicide as a result of the powers they still possess and never asked for. The Shop has

shelved the Lot-6 project and been covering up the deaths, but there was no way they could have predicted that Andy would meet and fall in love with another one of the participants, or that they would marry and have a child. It's revealed that Charlie displays not only her mother's telekinetic ability, but also pyrokinesis: the ability to start fires with her mind. Once The Shop gets wind of her abilities, the chase is on.

The story sounds a bit silly encapsulated like that, but King deftly handles the elements of the plot that are most at risk of falling into parody. His strength has always been the ability to ground the "super" in the natural. His best books are his most believable. Carrie is told through a series of transcripts and police reports, the way Bram Stoker told Dracula through a series of letters and journal entries, lending

the tale an air of authenticity. Pet Sematary spends so much time creating relatable characters that once they start dying and coming back to life, there's no time to question it because you are too busy being horrified.

In Firestarter, the devil is in the details. It's the specifics that make it seem so authentic. The way Andy's mental dominance ability is described as a push, and the effect it has on him physically (at one point it's suggested that it gives him "pin-prick hemorrhages") or the way King describes Charlie's ability. The temperature in the room will gradually increase and, when she really lets loose, a wave of heat will fly

through the room, only igniting into fire when it touches something flammable like a chair, or someone's flesh. Compare that mental image to, say, the kid who can start fires from X-Men 2, who just sort of shoots flame and throws it around wherever he wants. King's skill at describing what this kind of thing would actually be like if it were possible elevates the book beyond generic pulp.

Another great detail is the idea that Lot-6 is a mild form of LSD combined with a synthetic pituitary extract. Dr Wanless, the "mad" scientist in charge of the Lot-6 program, hypothesizes that "the natural counterpart of this substance is responsible in some way for the occasional flashes of psi-ability that nearly all human beings demonstrate from time to time. A surprisingly wide range of phenomena: precognition, telekinesis,

mental domination, bursts of super-human strength..." In fact, it might have been that sentence that really sold me on the book. It went a long way towards making the whole thing seem so real. Of course, in the novel's present, Dr Wanless is now obsessed with making sure Charlie McGee is killed because her powers are directly linked to her pituitary gland, which only really starts kicking in during puberty. In other words, the powers she already has could very well just be a fraction of what she will eventually

be able to do.

It's the accumulation of all of these little details, combined with its pacing and excitement, that makes the book great. King's imagination and creation of a plausible reality in which psi-powers exist was like cat-nip for my adolescent self, and the beat-up state of my paperback copy*** attests to how often I picked it up and re-read favorite passages.

About midway through the book, Charlie and Andy are captured by John Rainbird, The Shop's most capable and ruthless agent. The second half of the book is a weird combination of psycho-drama and scientific exploration of Charlie's psi-powers, in which Rainbird and The Shop try to gain the confidence of Charlie in order to test and harness her abilities while Andy tries to manipulate his hopeless situation to get one last chance to free Charlie.

I was always less enamored with the second bit, but it does set up a pretty great climactic sequence, one of the book's two phenomenal set pieces. Set pieces which lent themselves perfectly to the inevitable Hollywood adaptation...

Despite the fact that King's Firestarter is one of my favorite pieces of popular pulp, I had virtually no relationship to the Mark L. Lester film before writing this piece. Partially, I think, I just didn't want to have anything ruined for me. The book seemed perfect as it was, the action sequences already rendered cinematically on the page. The only relationship I did have to the film was the advertisements for its screenings on New

York's Channel 11 WPIX as the late movie, when they still did that.** ** Those commercials were centered on what turns out to be the climax of the film, in which Charlie's power is fully unleashed. Instead of waves of heat, as described in the novel, Charlie appeared to be firing giant flaming boulders at people, accompanied by sound effects that would normally accompany Patriot

missiles. I was so turned off, convinced that the film was terrible and a bastardization of something I cherished, that I guess I sort of boycotted it and never got around to actually seeing it until just before Halloween of this year, in preparation for this article.

It's funny that my prejudiced opinion of the film as being inferior was based on it changing things around, because it turns out to be one of the more faithful film adaptations of King's work that I've seen. This is significant for a few reasons: one, this is Stephen King we're talking about, the man who famously hated what Kubrick did to The Shining, which is actually one of the only good films made from his work. Two, sticking to

the book is sort of what's wrong with the film.

A quick aside about adapting novels into films: it's a complicated science. Especially these days, with internet fanboys needing to be placated while claiming to recognize that the novel and the film are two completely different mediums with different strengths and weaknesses. I have some of that fanboy desire for people to "get it right," even if my conscious mind knows that it's almost always better to approach it a different way.

Usually efforts to keep to the book, or to at least shoehorn in little details, just come off as embarrassing. Jurassic Park is a good example: all of Sam Jackson's dialogue, especially his lines describing "the lysine contingency," blow by so fast that if you haven't read the book they come off as gibberish. I understand why people like that movie: it's got at least one great set piece and also, you know, dinosaurs, but I'll always remember it as a disappointing, unsuccessful adaptation.*** ** I kind of wish it had strayed farther from its source. Watchmen is also sort of a good example, but that movie has a lot of problems. If there was ever something that shouldn't have been transplanted to another medium, it was the quintessential superhero comic about superhero comics (what superhero films need is a superhero film about superhero films.) This compounded with the fact

that Zack Snyder seems to have remembered every little detail about Moore and Gibbons' book without actually understanding any of it. This is all a long way of saying that, a few exceptions aside, I generally think it's better to take the spirit of something and a few details and then go your own way when it comes to adaptations.*** ***

The film version of Firestarter has the same big problem as Jurassic Park: trying to get all the little details in, but missing something from the spirit of the original. I was shocked as I was watching it - everything from the "pinprick hemorrhages" detail to each minor beat of the novel's plot is covered, but something about it just feels off, like it's just going through the motions. It somehow maintains the details

without the wonder.

The casting stretches from the pitch-perfect to the "I guess that makes sense" and on to "say what now?" Little Drew Barrymore is on-point as Charlie and David Keith is a serviceable Andy. The film kind of hinges on the relationship between Andy and Charlie, and Keith and Barrymore do a good job of making the audience feel that bond. Barrymore in particular gives a performance wise beyond her years, showing the weariness

from the stress her character is too young to have to deal with. She just needed to be cute in E.T., but here she's required to do the child actor thing where an eight-year-old can somehow preternaturally mimic adult behavior and she does it beautifully, for what it's worth. Martin Sheen is weirdly manic

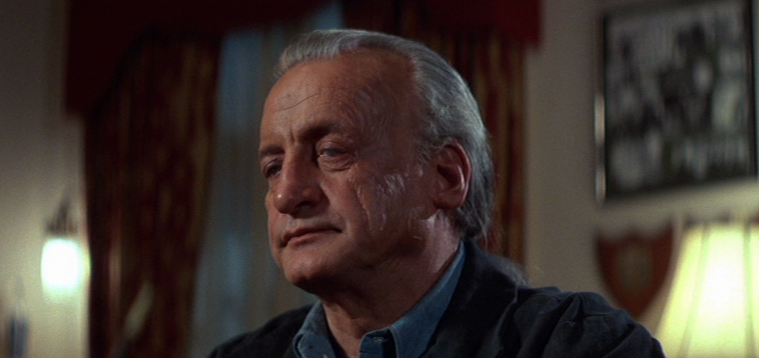

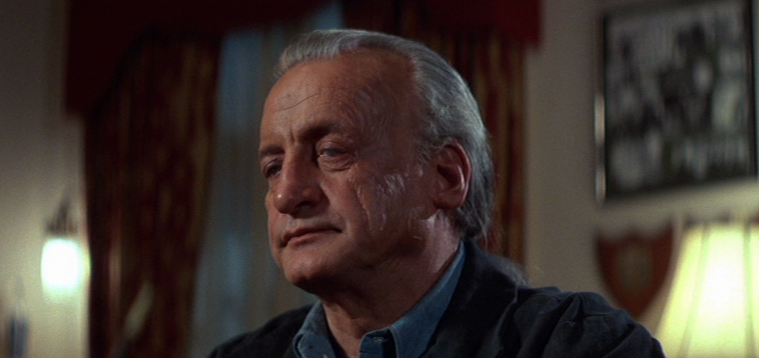

as Cap Hollister, commanding officer of The Shop, at times overplaying his excitement at what Charlie is truly capable of. Certainly we can all agree that when we think of a giant, one-eyed Native American government assassin, the first name that comes to mind is George C Scott. His Rainbird is both the weirdest casting choice as well as the weirdest performance. Early in the movie he's sufficiently menacing, but it's the film's second half where Scott's acting gets notably bizarre. The blackout sequence, in

which Scott pretends to be afraid of the dark to trick Drew Barrymore into comforting him, ultimately putting her trust in him, is...something to behold.

Stanley Mann's script hits all of the major beats of the novel. It's got the flashback to the Lot-6 experiment, the showdown at the Manders' farm, Rainbird's capture of the McGees at the lakehouse, the blackout that helps Rainbird manipulate Charlie, the climax at the stables. But somehow it feels like, while all of the details that absolutely had to be there are there, I wish the script were more meandering. I wish it had taken a little more

time with the experiment sequence and taken the opportunity to rearrange some of the more esoteric/psychologically interior elements of the novel's second half and strayed from them a bit. In other words, I actually wish they’d "Hollywooded" it up a bit.

All things considered, Lester's Firestarter is fine. It's got two main problems: it turns out that just keeping the important details from the novel weren't enough. In King's book, explaining things in detail helped to heighten the reality of the premise. In the film, having characters recite details in dialogue and having all the plot points line up isn't enough: the details needed to feel real. The few details the film gets wrong,

like Charlie's hair blowing around when she uses her power or the weird fireballs she shoots like rockets during the film's final showdown go a long way towards diluting some of the source material's magic.

Which brings us to the two set pieces. I've mentioned my problems with the climax: basically, while a lot of the details are right, the feeling is off. The sequence (indeed, the entire film) needed to have an infusion of wonder that what we're watching is really possible, rather than just hitting all the right action-sequence buttons. Dude on fire falling off window? Check. Fireball flying into military jeep? Check. But it's the showdown at

the farm in the middle of the film that really missed the mark for me. At its core, it's a Mexican Standoff that erupts into chaos and death. But the standoff element never feels tense, and the pacing of the editing once things go to hell feels a bit...unchaotic. It's as if the final cut included a half beat at the head of each shot before Lester yelled "Action!" It should feel terrifying, but it feels inadvertently slapstick.

I'm well aware that there's a chance I'm being a bit harsh on the film due to the fact that the novel is a cherished artifact from my adolescence, and as such I'm holding Lester's film to something of a higher standard. But trying to be as objective as I can, the film version of Firestarter is a crucial piece of evidence in proving the Shining/Watchmen theorem, which states "When adapting a book into a film - with

rare exceptions - pay attention to the spirit. Never mind the details."

~ NOVEMBER 24, 2011 ~

* Much of my relationship to King is tied to strong sense-memories. I have such a clear image of reading the last hundred pages of Pet Sematary at my grandparents' house - how I was terrified but could not put it down. It is such a powerful memory: I remember the feel of the chair's material and how I kept readjusting the way I was sitting in it to accommodate the several hours it took to get to the end. I remember sharing the same terrible sinking feeling Louis, the book's protagonist, experiences when he realized all that he had wrought. I feel sort of the same way about Sematary that I do about The Exorcist, that they are incredibly effective as horror vehicles because they spend so much time grounded in reality. The King book doesn't really get rolling until about 250 pages in and, a few incidents aside, the first section is basically just a realistic portrait of a marriage, a family and a surrogate father/son relationship, raising the stakes for when all of these bonds are suddenly placed in supernatural peril. And I've always found the early section of Friedkin's film to be the scariest part. Reagan getting CAT scans and peeing on the carpet, the audience knowing something is amiss but not knowing what it is, is scary in a way the second half of the film could only hope (pray?) to be.

** Two of the book's set pieces in particular are some of the most well-conceived and executed examples of action-writing that I've ever come across. They're violent and exciting. They're both scenes in which a tense stand-off erupts into panicked chaos, but you're never lost and confused while reading them. The scenes are so good in the books that the fact that they are sort of fumbled on the goal line in the film makes me resent it a little bit.

*** I still have the same copy, which I've been carting around with me for almost twenty years now. I even brought it with me once to an event at the Jacob Burns Film Center where King himself was going to be signing things, but it turned out he was signing copies of the then-brand new fifth or sixth book in the Dark Tower series. I never got into that whole series and felt weird standing in line to ask him to sign two old beat-up paperback versions of 30-year-old books (the other being my copy of Pet Sematary.) So they remain unsigned.

** ** WPIX's late movie is where I developed my weird fascination with the Demi Moore/Michael Biehn/Jurgen Prochnow Apocalypse movie The Seventh Sign which to this day I can not tell you is good or bad, but if it pops up while I'm channel-surfing, I am powerless to resist it. I used to watch whatever sitcom was in syndication just to see the commercials for the late movie to see when it would be on next. Just thinking about it is making my mouse-hand twitch. Gonna have to see it its streaming on Netflix. (Update from ten seconds later: It is.)

*** ** Weirdly, I also read the bulk of Jurassic Park at my grandparent's house. Or maybe that's not weird. Maybe I just read a lot when I was there.

*** *** Good examples of adaptations that go their own way and create an independent, successful work of art: Kubrick's The Shining, Mann's Miami Vice, Jonze/Kaufman's Adaptation. Notable exceptions to this rule: Linklater's A Scanner Darkly, Foley/Mamet's Glengarry Glen Ross. Novelist quite possibly most at the crux of this discussion: Phillip K. Dick. Probably unrelated aside: I can no longer remember Crichton's The Lost World, so I have no idea how faithful Spielberg's film is in terms of plot, but I remember that the basic idea was "there was another island with more dinos where the animals live naturally!" I do know this: Spielberg's The Lost World is about twenty times better than the his original Jurassic Park. It has two set pieces that hold up next to anything in that guy's career and, if there's one thing he's good at, it's set pieces. Re-watch the T-Rex attack on the trailer on the cliffside, and re-watch the Raptors hunting the hunters in the tall grass, then tell me I'm wrong. Spoiler alert: I'm right.