THE WHOLE HISTORY OF MY LIFE

THE SMARTEST MAN IN THE WORLD

page 2

christopher funderburg

What made (and makes) Darwin's insight so divisive is that it's so unpleasant, even terrifying: history's (and evolution's) flow is built upon the cruel fact of mass death, generation after generation being born only to die and leave the fittest few behind. Darwin's famous "there is grandeur in this view of life" finale to On the Origin of Species is an attempt to come to terms with the almost unbearable idea that biology is regulated and guided by such a monstrous principle. When I read Darwin's words "from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved," he almost has me believing that his understanding of evolutionary biology is anything less than super fucking depressing. Darwin's struggle to come to terms with his scientific discovery makes for a telling contrast to Langan's delusions of grandeur: Darwin's insight was into the insignificance and fragility of life, while Langan gloms onto transparent power fantasies that seek to reorganize reality altogether. Darwin eloquently searches for beauty in his truth, while Langan proposes an ugly unreality in which self-satisfied blowhards decide when I can use my agricultural resources (i.e. eat) and with whom I can have a family. There's a sad tension in Langan between his congenital mental gifts and the ways reality has otherwise thwarted him at every turn: abusive step-fathers and absentee parenting, indifferent teachers and academic failure, health problems and a life-path leading to nowhere. On a macro level, intelligence helps humanity as a species be one of the most dominant,* but on a micro level Langan's intelligence fails to do him any particular favors, aside from being a footnote in the Guinness Book of World Records. When Langan speculates on a nebulous conspiracy of political correctness that caused his record to be removed from the book ("I guess the Guinness Book fell victim to P.C."), it's difficult to fathom how someone dealt such enormous mental advantages is actually had their only accomplishment taken away. But it again squares with Darwin's idea: the macro level matters much more than the micro level - the idiot bastard of his idea, Social Darwinism, gets this point entirely wrong: individuals are far more at the mercy of the flock than human beings really care to consider. What's more, the evolution of the flock demands large-scale annihilation of the individual. And the capper is that evolution isn't really moving in a clear direction of improvement: the "fittest" organism is frequently one that is simpler (it could, in Langan's once again evolutionarily wrong-headed terms have smaller "cranial capacity") or otherwise failing to meet the common synonymizing of "evolved" with "advanced" or "improved:" humanity's next evolutionary wrinkle could easily be one that finds us stupider or flabbier or as gaunt albino anemics totally lacking in thick lustrous mustaches. Of course Langan sees Darwin "down in the toilet;" Darwin's view of life (containing grandeur or not) threatens Langan's fragile self-image and fanciful aspirations - it is any wonder that Langan sees his battle with the academic establishment in Darwinian terms: they're "hogging all the resources."

What made (and makes) Darwin's insight so divisive is that it's so unpleasant, even terrifying: history's (and evolution's) flow is built upon the cruel fact of mass death, generation after generation being born only to die and leave the fittest few behind. Darwin's famous "there is grandeur in this view of life" finale to On the Origin of Species is an attempt to come to terms with the almost unbearable idea that biology is regulated and guided by such a monstrous principle. When I read Darwin's words "from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved," he almost has me believing that his understanding of evolutionary biology is anything less than super fucking depressing. Darwin's struggle to come to terms with his scientific discovery makes for a telling contrast to Langan's delusions of grandeur: Darwin's insight was into the insignificance and fragility of life, while Langan gloms onto transparent power fantasies that seek to reorganize reality altogether. Darwin eloquently searches for beauty in his truth, while Langan proposes an ugly unreality in which self-satisfied blowhards decide when I can use my agricultural resources (i.e. eat) and with whom I can have a family. There's a sad tension in Langan between his congenital mental gifts and the ways reality has otherwise thwarted him at every turn: abusive step-fathers and absentee parenting, indifferent teachers and academic failure, health problems and a life-path leading to nowhere. On a macro level, intelligence helps humanity as a species be one of the most dominant,* but on a micro level Langan's intelligence fails to do him any particular favors, aside from being a footnote in the Guinness Book of World Records. When Langan speculates on a nebulous conspiracy of political correctness that caused his record to be removed from the book ("I guess the Guinness Book fell victim to P.C."), it's difficult to fathom how someone dealt such enormous mental advantages is actually had their only accomplishment taken away. But it again squares with Darwin's idea: the macro level matters much more than the micro level - the idiot bastard of his idea, Social Darwinism, gets this point entirely wrong: individuals are far more at the mercy of the flock than human beings really care to consider. What's more, the evolution of the flock demands large-scale annihilation of the individual. And the capper is that evolution isn't really moving in a clear direction of improvement: the "fittest" organism is frequently one that is simpler (it could, in Langan's once again evolutionarily wrong-headed terms have smaller "cranial capacity") or otherwise failing to meet the common synonymizing of "evolved" with "advanced" or "improved:" humanity's next evolutionary wrinkle could easily be one that finds us stupider or flabbier or as gaunt albino anemics totally lacking in thick lustrous mustaches. Of course Langan sees Darwin "down in the toilet;" Darwin's view of life (containing grandeur or not) threatens Langan's fragile self-image and fanciful aspirations - it is any wonder that Langan sees his battle with the academic establishment in Darwinian terms: they're "hogging all the resources."

Additionally, running throughout his books, Gould repeatedly takes on conventional notions of intelligence and the faulty ways in which it's measured and described. His excellent The Mismeasure of Man is one of the definitive statements on the nature of human intelligence and a masterful debunking of biological determinism, a concept that is one of the more virulent strains of Social Darwinism. Gould is specifically going after the idea that black people are socially disadvantaged because they are less biologically equipped to succeed than the other races and one of Gould's main targets is the idea of intelligence being subjected to an ordinal ranking that arises because of humanity's "propensity for ordering complex variation as a gradual ascending scale."** He's taking on Langan's claim to fame directly: he thinks that "I.Q." is an absurd idea that suffers from "our tendency to convert abstract concepts into entities." That is, rating Langan versus Darwin on a scale of mental power rating 120 versus "190-210" is a ridiculous idea that reality seems to bear out: if Langan's so much smarter than Darwin, how come his ideas are so much stupider? There's another interesting layer here if we add in Darwin's life story: Charles Darwin's older brother Eramus Alvey Darwin was considered by everyone who met the brothers to possess the far superior mind: Erasmus breezed through school and was beloved by his teachers, he was out-going and effortlessly bright and engaging. By comparison, Darwin was described by his teachers as a dullard and preferred collecting minerals and fossils to studying. In his early adult life, he spent most of his time hunting and idling about: between the two brothers, it was clear which was destined for greatness and which was destined for comfortable aristocratic mediocrity. In light of this, Darwin's greatness and Langan's sub-mediocrity becomes even more mysterious - is apparent intelligence really such a marginal factor in intellectual success? What is it that we even mean by intelligence? Morris, as a documentarian, has found the perfect subject to illuminate a such a deeply scientific concern.

In another essay, one on W.A. Mozart's childhood, Gould talks about the concept of intellectual compartmentalization: even at age 5, Mozart was clearly a genius - well, a genius in so far as that he was already able to compose symphonies, the quality of which exceeding what most human beings would ever be capable. Gould makes the point that the earliest accounts of Mozart take special note of his childishness: he's a regular kid (who is easily distracted by the pet housecat) in all senses save his musical proclivities. That's important for these early accounts because the initial concern with Mozart was that he was a fraud, a midget adult posing as a child prodigy. So, his musical genius is somehow held in a different mental compartment from his otherwise normal intellectual development which finds him a regular little snot-nosed brat. The idea that general I.Q. can be measured along a linear path is in opposition to the notion of compartmentalized intellectual capacities: it's an all or nothing system which places Darwin below Langan without having any way to account for the fact that Darwin could be a genius at some things (I personally feel that Darwin's true talent was humility and the ability to see man as he exists in nature by dropping the theologically-tinged notion of man's Importance and Destiny) but a bit of dullard at other (such as things that I.Q. tests measure like arranging number sequences and spatial relationship problems.) Gould's essays are littered with accounts of compartmentalized intelligences, like Vladimir Nabokov: mediocre lepidopterist, brilliant novelist. Combined with Morris' film, the Gould essays make me question what is even meant by intelligence: clearly some people are better at things than other people, but to what extent is the mind like a muscle? After all, Langan is a somewhat naturally large guy, but it is his dedication to body-building that makes him in the rippling mass of muscles and popping veins that he is today. If muscles can be exercised and improved, it should just as obviously be the case that a mind can be worked out and expanded - that is, maybe intelligence is never a single set quantity, but a series of inter-related pieces each with its own natural capacity that can be strengthened or weakened depending on use and disuse. Seen in this light, it's not hard to untangle the central question, "how could such a smart person be so fucking stupid?" If anything, the I.Q. test scores have gotten in the way of Langan seeing himself clearly: I myself know what its like to be fooled by that kind of praise and walk around thinking how I'm such a genius even though I haven't accomplished shit.

In another essay, one on W.A. Mozart's childhood, Gould talks about the concept of intellectual compartmentalization: even at age 5, Mozart was clearly a genius - well, a genius in so far as that he was already able to compose symphonies, the quality of which exceeding what most human beings would ever be capable. Gould makes the point that the earliest accounts of Mozart take special note of his childishness: he's a regular kid (who is easily distracted by the pet housecat) in all senses save his musical proclivities. That's important for these early accounts because the initial concern with Mozart was that he was a fraud, a midget adult posing as a child prodigy. So, his musical genius is somehow held in a different mental compartment from his otherwise normal intellectual development which finds him a regular little snot-nosed brat. The idea that general I.Q. can be measured along a linear path is in opposition to the notion of compartmentalized intellectual capacities: it's an all or nothing system which places Darwin below Langan without having any way to account for the fact that Darwin could be a genius at some things (I personally feel that Darwin's true talent was humility and the ability to see man as he exists in nature by dropping the theologically-tinged notion of man's Importance and Destiny) but a bit of dullard at other (such as things that I.Q. tests measure like arranging number sequences and spatial relationship problems.) Gould's essays are littered with accounts of compartmentalized intelligences, like Vladimir Nabokov: mediocre lepidopterist, brilliant novelist. Combined with Morris' film, the Gould essays make me question what is even meant by intelligence: clearly some people are better at things than other people, but to what extent is the mind like a muscle? After all, Langan is a somewhat naturally large guy, but it is his dedication to body-building that makes him in the rippling mass of muscles and popping veins that he is today. If muscles can be exercised and improved, it should just as obviously be the case that a mind can be worked out and expanded - that is, maybe intelligence is never a single set quantity, but a series of inter-related pieces each with its own natural capacity that can be strengthened or weakened depending on use and disuse. Seen in this light, it's not hard to untangle the central question, "how could such a smart person be so fucking stupid?" If anything, the I.Q. test scores have gotten in the way of Langan seeing himself clearly: I myself know what its like to be fooled by that kind of praise and walk around thinking how I'm such a genius even though I haven't accomplished shit.

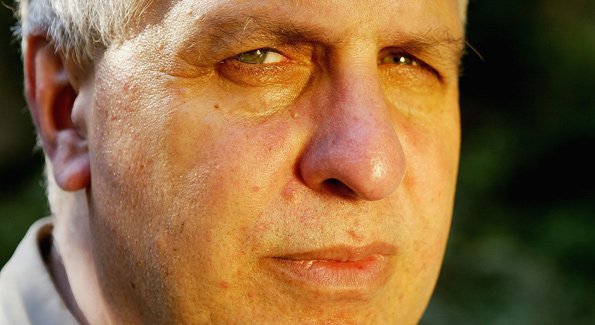

And that brings us to Errol Morris' obsessive theme: self-deception. Checking his twitter feed is one of the more enjoyable routines of my day and one of his recent comments speak to this essay almost directly: "Stupid

people are going to take over the world, but that doesn't mean we should make it easy for them. (And what if I'm one of them?)"*** You can see a reflection of Langan's worldview in there (i.e. the world needs to be saved from stupid people), a bit of the drive that causes him to make movies (trying to stop stupidity by dissecting it with a camera) and his understanding/fear that he could just be lying to himself. Langan is the perfect subject around which to weave the theme of self-deception and not just because of his complete lack of self-awareness. It should be obvious to even the most uncritical observer that despite his ambitious schemes, Langan is scarcely qualified to run a Laundromat let alone the world, but the camera adds another dimension in that we can see how Langan carries himself. He knows well enough to pay lip service to the idea that he might not come across as the ideal candidate for world-wide overlord when while discussing his high test scores he says "Do I think that makes me better than everybody else? No. I still work in a bar." He goes out of his way to say the right things as far as egalitarianism is concerned: the high I.Q. community/world rulers would not live better or be given any privileges above anyone else. (Ruling the world and making all the major decisions aside.) He plays up his blue-collar, everyman credentials knowing that such poses go over really well in the U.S.A. - but there's something about the way he carries himself, the smug little chortles and the abrasive gleam in his eye that pretty well belie his actual contempt for the world. When Morris asks him who could provide the theoretical world-saving ethical framework, Langan replies "Who knows? It could be you," but he has a sleepy-lidded, faux-thoughtful air that betrays his actual feelings. His words say "hey, anybody could be as smart as me" but his tone says "of course you aren't but you should be flattered I'm being so generous to give you even the pretense of the benefit of the doubt."**** But that's what makes it such a fascinating film: there's no way to really know what Langan thinks about himself or the world around him. He's smart and articulate enough to be careful with what he says, even though his ideas and body language betray him. He talks about getting thrown out of college and accomplishing nothing beyond working in a bar, so on some level he understands that he got thrown out college and works in a bar - but how much is he deceiving himself about what it means to get thrown out of college and work in bar? Does he even engage the question, "what if I'm one of the stupid people?"

And that brings us to Errol Morris' obsessive theme: self-deception. Checking his twitter feed is one of the more enjoyable routines of my day and one of his recent comments speak to this essay almost directly: "Stupid

people are going to take over the world, but that doesn't mean we should make it easy for them. (And what if I'm one of them?)"*** You can see a reflection of Langan's worldview in there (i.e. the world needs to be saved from stupid people), a bit of the drive that causes him to make movies (trying to stop stupidity by dissecting it with a camera) and his understanding/fear that he could just be lying to himself. Langan is the perfect subject around which to weave the theme of self-deception and not just because of his complete lack of self-awareness. It should be obvious to even the most uncritical observer that despite his ambitious schemes, Langan is scarcely qualified to run a Laundromat let alone the world, but the camera adds another dimension in that we can see how Langan carries himself. He knows well enough to pay lip service to the idea that he might not come across as the ideal candidate for world-wide overlord when while discussing his high test scores he says "Do I think that makes me better than everybody else? No. I still work in a bar." He goes out of his way to say the right things as far as egalitarianism is concerned: the high I.Q. community/world rulers would not live better or be given any privileges above anyone else. (Ruling the world and making all the major decisions aside.) He plays up his blue-collar, everyman credentials knowing that such poses go over really well in the U.S.A. - but there's something about the way he carries himself, the smug little chortles and the abrasive gleam in his eye that pretty well belie his actual contempt for the world. When Morris asks him who could provide the theoretical world-saving ethical framework, Langan replies "Who knows? It could be you," but he has a sleepy-lidded, faux-thoughtful air that betrays his actual feelings. His words say "hey, anybody could be as smart as me" but his tone says "of course you aren't but you should be flattered I'm being so generous to give you even the pretense of the benefit of the doubt."**** But that's what makes it such a fascinating film: there's no way to really know what Langan thinks about himself or the world around him. He's smart and articulate enough to be careful with what he says, even though his ideas and body language betray him. He talks about getting thrown out of college and accomplishing nothing beyond working in a bar, so on some level he understands that he got thrown out college and works in a bar - but how much is he deceiving himself about what it means to get thrown out of college and work in bar? Does he even engage the question, "what if I'm one of the stupid people?"

In his excellent NY Times blog, Morris has written a lot recently about the Dunning-Kruger effect: it's based a study that shows how incompetent people are unaware of their own incompetence; people who did badly on a test are more likely to rate themselves as having done well than those who actually did well. It's the scientific demonstration of Christian Langan's entire problem: you can be one of the stupid people and not even know it. Taken a step farther, it's human nature to be oblivious to the ways in which we are stupid. Hilariously, Langan sums up the effect perfectly, but seemingly without an ounce of awareness that it could apply to him: "The stupid person thinks that he is as smart as or smarter than the smart person. And therein lies his stupidity." Just as we took apart the concept of intelligence, stupidity needs to be taken apart in the same way: you can be very stupid in some compartments while very intelligent in others. And you will likely not be able to tell the difference. Normally, I'm not a fan of opinionated grumps like Fran Leibowitz or Richard Dawkins because their certainly is extremely off-putting - on the surface of things, Morris has a similar curmudgeonly, dismissive personality. What makes his work more valuable is his obsession with self-deception and constant acknowledgement that there's a chance he's gotten the situation entirely wrong. I think of his early film Vernon Florida which towards the end features an elderly couple showing off a jar of "growing sand." In early interviews, Morris would cite them as example of nutjobs with some glaring intellectual deficiencies: sand doesn't grow. But later in life, Morris found out that certain sand (from the area where the couple got their jar-full) contains a moss-like bacteria that builds up... causing the appearance of growth. Morris was wrong and the yokels were right: sand does grow. Morris mentions it in interviews because it's important for him to understand self-deception as a fundamental human trait: he's afflicted by it just as much as anyone! On the flip side, getting the truth right matters to Morris. He (rightly) detests post-modernism and its wishy-washy concept of reality "existing" in only an abstract sense, truth being relative and all that. Morris has said, "Tell someone on death row for a crime they didn't commit that there's no such thing as an objective reality." To me, it feels like the scientist in him poking out, demanding a fidelity to verifiable reality.

If I leaned on Gould a lot in this essay, it's because I genuinely wouldn't have viewed The Smartest Man in the World in the same way without having spent time enjoying his work. I certainly wouldn't have read On the Origin of Species without Gould's enthusiasm for Darwin and his professorial insistence to "always start with the source material." But it's rare that I encounter artworks that are thematically and intellectually well-constructed enough to warrant any kind of application of science-y thought. It's all this that confirms my view of Morris as a kind of cinema scientist, a filmmaker who approaches art with a greater argument about the nature reality and its participants - a greater argument that would be tempting to call "philosophical" if Morris weren't so insistently in pursuit of empirical truth. I've always thought of art and science as flipsides of the same coin in that both are attempting to describe reality: science under a microscope looking from the outside in; art from the inside out, how it feels to "be." Errol Morris' films feel essential because they so deftly combine "the outside in" and "the inside out:" in a funny way, his empathy for Christian Langan derives from the fact that he explores the mind of the world's smartest man with such a removed and analytical approach. Morris definitely isn't running an ad campaign for humanity, but that's because he actually wants to understand his subjects and bring his audiences a no-bullshit presentation of the truth. That he also somehow manages to make the films hilarious and charming feels like a magic trick. I have no idea how he does it: I'd probably chalk up his talent for infusing high-minded epistemological ruminations with irresistible razor-sharp humor to some magical cinematic alchemy, if I hadn't learned that it's probably just my own stupidity getting in the way.

* Gould cleverly points out that while humanity is commonly seen as being the world's dominant species, a much better case can be made that bacteria is actually the organism that has come out on top of the heap.

** It's also nice to note that a particular point that Gould demolishes is "craniometry," a persistent fallacy from the history of science and one of which the large-headed Langan is notably fond.

*** Another twitter quote that would have worked almost as well: "I'm trying to decide if my brain is my friend. It seems friendly at times. But now, less and less often. (OK. I decided. It's not.)"

**** I'd also like to mention that a couple years ago I saw Langan on a game-show called "1 vs. 100" and he was milking his "gosh, everybody around is smart, I have so much respect for everyone" shtick to a high degree. The concept of the show is that 1 really smart person goes against a group of 100 schmoes is a trivia contest. They get asked a question and given 4 choices for the answer, the genius makes his guess and the whatever the majority of the 100 select is their answer. The whole thing is essentially an extended take on the "Ask the audience" option on Who Wants to be a Millionaire. I didn't watch the whole episode or anything (I do remember that a trio of bubbly blonde triplets were part of the 100 and the camera kept zooming in on their bouncing cleavage), but at the time I was struck by how humble Langan was being. Having watched The Smartest Man in the World a couple more times since then, I'm now convinced his humility is a self-serving pose and that Morris just didn't include all that much of the posing in the doc - just enough to get his point across.

- christopher funderburg

november 23, 2010

RELATED ARTICLES

<<Previous Page 1 2 Next Page>>

home about contact us featured writings years in review film productions

All rights reserved The Pink Smoke © 2010