1/21/7 - 1/30/7

john cribbs

In October 2006, Funderburg and Cribbs set out to watch at least 200 movies over the course of the next 200 days. They both watched a different slate of films and wrote about every single one; from epic high art masterpieces such as Max Ophul's The Earrings of Madame de... to lesser films by great directors like Richard Linklater's It's Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books to idiotic dreck like A Night at the Museum. In sections spanning 10 days at a time, The Pink Smoke is reprinting their writings about the grueling experiment in cinematic endurance.

<<click here for 1/11/7 - 1/20/7>>

1.21. La Haine.

I'm here today to put a twig between the La Haine love-bicycle's spokes. I don't think I've read a single review or met any person that didn't praise it as the second coming of Scorsese. When the movie came out in 1995, I was busy filling the mental crater of resentment and loathing towards my sophomore year of high school by feasting on as many of what I considered "subversive" films as possible. At the time, those were the then-exciting new American independents, mostly stuff like Clockers and Dead Man, and out-there foreign films like Santa Sangre and movies by Peter Greenaway. When Hate (as it was released in the US) turned up on the shelf of the video store where I worked (Blockbuster – you may have heard of it), it seemed like the perfect movie. "Hate"...I'm familiar with this emotion. Then I actually watched it. Even at that time, when my wet-behind-the-ears counter jockey thought Miller's Crossing was the apex of cinematic achievement, La Haine felt like a fraud. With its unabashed approach to racism and antidisestablishmentarian mantra "Jusqu’ici, tout va bien" ("Up til now, everything's fine"), its grainy black and white photography and urban locations, the energetic camerawork and in-your-face direction, the film just seemed forced. Phony. Overcooked. And since I didn't have any film nerd friends and didn't follow its critical response in the States, I assumed that nobody paid the movie much mind right up until its recent Criterion release.

And with the wave of enthusiastic reviews of the new dvd I figured it was as good a time as any to give this one a reappraisal. My reaction was pretty much the same: the movie uses its quick editing and unrelenting pace to mask that there's really not a lot going on. A group of three friends (no plot summary can resist throwing in "one Jewish, one Black, one Arab" – really makes you notice how the Ocean's Eleven cast is never listed as "eight Whites, two Blacks, one Asian") living in the banileues of paris spend a day running around with a policeman's handgun lost during a violent riot. The surliest of the bunch, Vincent Cassel, is determined to kill a cop if one of their rioting friends dies of his injuries in the hospital. The actors are fine, but their rigor morale of running, confronting authority, running, swearing, smashing and running gets fairly repetitive fairly quickly. A combination of two shaky subgenres (it's like a French cocktail of Kids and Menace II Society), La Haine coasts on the simple theme that "hate breeds hate," violence begets violence, turtle bites snake and society's just never going to get better, is it? An overrated underrated movie, now officially an overrated movie.

1.22. The Bigamist.

Ida Lupino is my Classic Hollywood wet dream: a smart, beautiful, talented actress/writer/director, not just another pretty face. This 1953 film is a taut variation of the old black and white "issue" short ("Wash Your Hands!" or "Your Neighbor Could Be a Commie!") which Lupino turns into a smart melodrama. Years yet before he'd be reciting Shakespeare with Keith Moon at Sam Peckinpah's birthday party, Edmond O'Brien plays a man living a secret double life with Lupino, who he knocked up and nobly married despite the technicality of already being hitched for eight years to Joan Fontaine (who actually looks like - eh - Ana Gasteyer?) Edmund Gwenn, who uncovered giant mutant ants in Them! here uncovers the big secret, and O'Brien has to decide how he's going to clean up his own mess.

It's funny to see how much sympathy Lupino (the director) has for O'Brien's character, that this isn't a movie condemning a man for manipulating two women but rather a kind of naively romantic story about how some guys just can't bring themselves to spoil their marriage with news of infidelity, and it escalates from there. That's something that could easily be read as tactless and jejune, but Lupino is too smart a filmmaker for that - what she's actually done is reversed the roles so that O'Brien plays the role typically enacted by a female character. Coming after her grim rape drama Outrage, Bigamist shows that Lupino wasn't a director of "women's issue" films but rather a woman director interested in issues of dependence and independence in relationships in general. God, she's awesome...what other director would have described themselves as "a poor man's Don Siegel?" As an actress she's amazing to watch on screen, so that even the dangerously pro-bigamy ending (!) doesn't distract from the interesting parts of the movie.

1.23. Mutual Appreciation.

Someone informed me with great reverence in his voice that this film was made for seven thousand dollars with a ten-man crew. My main question for the filmmakers is: where did the money go? What were the eight guys not running the static camera or holding the boom up to? This hipster version of a Cassavetes-style 16mm black & white improvisational indie garnered some attention from the art house crowd, i.e. nihilistic Brooklynites who love watching renditions of their bespectacled guitar-playing scraggly-haired selves on screen. Andrew Bujalski, along with the equally talentless Joe Swanberg, has become the patron saint of this bullshit "Mumblecore" movement that not only mumbles but mocks and grins out the side of its mouth in self-satisfaction. At least Bujalski, unlike his contemporary douchebag, doesn't just film a boring porno with ugly people: there's actually some semblance of plot to Mutual Appreciation, but it takes the co-star/director an hour and a half of this thing to realize what he wants to show is how these people can't muster up the energy to ever change their dog-paddling drab of existence.

Someone informed me with great reverence in his voice that this film was made for seven thousand dollars with a ten-man crew. My main question for the filmmakers is: where did the money go? What were the eight guys not running the static camera or holding the boom up to? This hipster version of a Cassavetes-style 16mm black & white improvisational indie garnered some attention from the art house crowd, i.e. nihilistic Brooklynites who love watching renditions of their bespectacled guitar-playing scraggly-haired selves on screen. Andrew Bujalski, along with the equally talentless Joe Swanberg, has become the patron saint of this bullshit "Mumblecore" movement that not only mumbles but mocks and grins out the side of its mouth in self-satisfaction. At least Bujalski, unlike his contemporary douchebag, doesn't just film a boring porno with ugly people: there's actually some semblance of plot to Mutual Appreciation, but it takes the co-star/director an hour and a half of this thing to realize what he wants to show is how these people can't muster up the energy to ever change their dog-paddling drab of existence.

Hip humor (take that, Pete Seeger!) and detached indifference are what's on display, so if that's the kind of thing you want from your moving pictures there you have it. I've taken some heat recently for my positive (or I should say non-negative) opinion of The Puffy Chair, but even though that movie had the same kind of self-obsessed assholes directing and starring as self-obsessed assholes, it also had actual scenes and scripted dialogue. The improvised banter, when it isn't mercifully unintelligible under the noisy ambient soundtrack, is composed entirely of banal everyday back-and-forth and retarded non-sequitors. Oh good, another scene with people sitting around talking about nothing! It's a relief that most of the film community seem to be dismissing these little projects, otherwise we could all look forward to a bleak future for American independent cinema: a hipster's home movies.

1.24. Ravenous.

Yet another film I've been aware of for years but never had any real intention of seeing until recently when I discovered a used vhs copy in a video store bargain bin for a buck. The cast is comprised entirely of guys I always think I like who have never really reached that high mark of notable greatness. Guy Pearce is great as a smarmy villain in The Count of Monte Cristo, but is whiny and bland in overrated fare like Memento and LA Confidential. Robert Carlyle's intensity in Riff Raff and Trainspotting is fun, but tends to go over the edge (or be completely incomprehensible beneath his Scottish brogue). Jeffery Jones is an icon of sorts, but has that whole child pornography thing looming over him, and Jeremy Davies has been steadily squandering the promise of his debut performance in Spanking the Monkey. Neil McDonough... I guess I like Neil McDonough.

Yet another film I've been aware of for years but never had any real intention of seeing until recently when I discovered a used vhs copy in a video store bargain bin for a buck. The cast is comprised entirely of guys I always think I like who have never really reached that high mark of notable greatness. Guy Pearce is great as a smarmy villain in The Count of Monte Cristo, but is whiny and bland in overrated fare like Memento and LA Confidential. Robert Carlyle's intensity in Riff Raff and Trainspotting is fun, but tends to go over the edge (or be completely incomprehensible beneath his Scottish brogue). Jeffery Jones is an icon of sorts, but has that whole child pornography thing looming over him, and Jeremy Davies has been steadily squandering the promise of his debut performance in Spanking the Monkey. Neil McDonough... I guess I like Neil McDonough.

Anyway, this is the first movie I've seen in a while where the winter setting made me feel cold watching it. Director Antonia Bird does a servicable job with the horror aspect of the movie, especially in a few memorable scenes where something isn't right but the characters can't figure out what's wrong until it's too late. The weird tone of the movie reminded me of a Japanime horror film: surreal situations and vulnerable flesh. It's the comedy that falls a little flat. Cannibalism is actually a scary idea but it seems like filmmakers don't trust audiences to take it seriously, hence attempts to turn cannibalism movies into black comedies (and the humor in this one has nothing on Cannibal: The Musical). The whole "eating flesh makes you strong" is played a little too literally, but I like the film's mythology that consuming another person transforms the eater into a demon. Again, the kind of weird script idea that seems like something out of warped Japanese cartoon. So a passable film with good atmosphere, decent actors and a really interesting soundtrack, bizarre banjo music by Michael Nyman and distorted electronic ambience from Damon Albarn.

1.25. Nadja.

Black and white photograph loves Elina Lowensahn, and the best that can be said about this missed opportunity is that it's a love letter to her natural cinematic mystique. Rounding out the informal 90's post-modern female vampire trilogy that included Abel Ferrara's The Addiction and John Landis' Innocent Blood, Nadja is known as being like a Hal Hartley movie directed by David Lynch (who exec-produced and makes a cameo as a morgue attendant), a reputation impossible to shake since the movie is produced by Mary Sweeney and features Hartley regulars Lowensahn and Martin Donovan. The film flitters between oblique Lynch-like non sequitors ("My hair feels drunk") and poetic Hartley-esque asides ("Once or twice a day I see a woman on the subway I feel I could fall in love with") without capturing the mystery or playfulness of either director.

Unshackle director Michael Almereyda from the inevitable comparisons and what you're left with is a modernization of Dracula (and a little bit of a Hamlet update, predating Almereyda's feature-length Hamlet relocation) heavy on exposition and short on execution. Lowensahn plays Nadja, the existential and allegedly blood-thirsty daughter of the Transylvanian count who is tracked down by Peter Fonda's Van Helsing as she visits her pacifist vampire brother Jared Harris, poster boy for the "What's My Appeal?" campaign (although he's actually better here than he's been in anything else). The film moves back and forth between philosophical interludes and oblique subplots when it should have stuck to the story.

1.26. A is for The Agronomist.

"Jonathan - you can not kill truth! You can not kill justice!" Jean Dominique makes this powerful statement to the filmmaker in 1991, nine years before his assassination outside the influential radio station he created and was an obstinate voice from in his homeland of Haiti, a station that was shut down twice following dictatorial coups only to rise again from the ashes to question and criticize the running of the war-torn island. He also states: "If you see a film correctly, the grammar of the film is a political act," and Jonathan Demme has created the perfect conduit to Dominique's life and work, a political documentary that's more interested in and about people.

Dominique himself is an ideal subject, an excellent speaker and storyteller who modestly refers to himself as "an agronomist" (one of his sisters compliments the handle by quoting their father's belief that one who does not cultivate the land does not own it) and brushes off his courageous career as "risky business." Demme also brings out the playful personality in him, which you'd think would be buried beneath the years of threats, suppression and exile to the United States. Spanning a decade, the movie is no less a history of the country in the latter half of the 20th century - a supposition that no ruling military power deserves to govern a nation which tragically ends with the death of its hero, whose faith in the human spirit is imprinted on Demme's passionate film essay.

1.27. B is for Britannia Hospital.

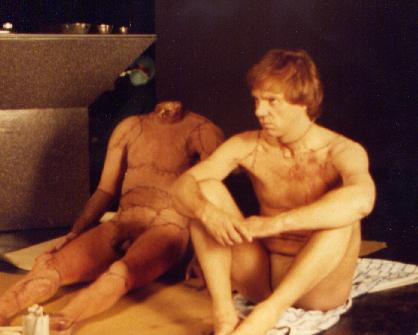

After finishing David Sherwin's book, I knew I had to finally take the plunge and view Britannia Hospital, the third collaboration of Sherwin, Lindsay Anderson and Malcolm McDowell. I had avoided it because I didn't want the movie to spoil If... and O Lucky Man, two of the best British films from the last 40 years, the way recent films have polluted my otherwise unwavering love for David Cronenberg and Roman Polanski. In flat terms, it's really great, if not the masterpiece of its predecessors and I'm glad I finally let myself discover it. Centered around a day of protesting against privileged private patients coinciding with a visit from the Queen Mother, the film also features the Frankenstein-like experiments of Professor Millar (Graham Crowden, reprising one of his roles from OLM!), spied upon by McDowell as journalist Mick Travis.

After finishing David Sherwin's book, I knew I had to finally take the plunge and view Britannia Hospital, the third collaboration of Sherwin, Lindsay Anderson and Malcolm McDowell. I had avoided it because I didn't want the movie to spoil If... and O Lucky Man, two of the best British films from the last 40 years, the way recent films have polluted my otherwise unwavering love for David Cronenberg and Roman Polanski. In flat terms, it's really great, if not the masterpiece of its predecessors and I'm glad I finally let myself discover it. Centered around a day of protesting against privileged private patients coinciding with a visit from the Queen Mother, the film also features the Frankenstein-like experiments of Professor Millar (Graham Crowden, reprising one of his roles from OLM!), spied upon by McDowell as journalist Mick Travis.

The film plays the absurdities of Marxism against the rigid protocol of state (here in the guise of a hospital), and it's a credit to Anderson that the satire is never ridiculously obvious. This film's Crusaders, the picketers, are as mindlessly guided as the revolutionaries in Network, preaching humanity while stopping ambulances at the gate to check union cards. "You wouldn't know Karl Marx from a toffee apple," an executive accuses the idealist leader of the kitchen workers' revolt, who's one haircut away from selling out himself. Some incredible touches: the Queen's entrance, as brilliantly surreal as If...'s chaplin the drawer, and the swift change from the striking staff singing "We Shall Not Be Moved" to "Auld Lang Syne" at the prompting of a sector administrator. With references to the early films - there's even a Rudyard Kipling Wing - Britannia is as self-aware as it is socially dissecting: I'm surprised that it doesn't have a better reputation (Vincent Canby called it the greatest British film ever made!) Crowden's ending monologue is also pretty amazing. Appearances by Joan Plowright, Mark Hamill, John Gielgud, Alan Bates, Arthur Lowe (whose otherwise hilarious death scene was booed by audiences due to the actor's recent passing when the film was released) and Richard Griffiths as hospital DJ Cheerful Bernie.

1.28. C is for Clean.

Hard to say how I feel about Olivier Assayas. He's certainly talented and has ideas, but I feel like I never have any idea what it is he's interested in beyond his film's abstractions: pop cultural fixtures. The lives of artists and entertainers. Drugs. Lesbianism. The face of Maggie Cheung. Whereas Wong Kar-Wai made a tapestry of quietly pained thespians, Assayas has made a muse of Maggie Cheung, content to give her a character name, a broad situation, and then just release her into the world in front of his camera. Clean is better than Irma Vep, but it's not as good as the underrated Demonlover, which may have benefited from Cheung's absence since it therefore got the director's full attention and an actual plot, albeit a vague and wildly convoluted one. The character she gets here (in her first movie with Assayas since he became her ex-husband) is Emily Wang, a former V-Jay and musician/junkie who's hit rock bottom after losing her rocker husband to drugs and leaving prison life for a nonexistence in Paris while her son is under the care of in-laws Martha Henry and Nick Nolte. Cheung owns the movie, but while it's never boring (maybe 20 minutes too long), the events of the film run together with no scenes sticking out. Interestingly, Emily Haines and Tricky play themselves as total snobby jerks.

1.29. D is for Down to the Bone.

Recovering Druggie Mom Movie Part 2. I'll clear something up: watching people do drugs is not aesthetically pleasing. It can be shot in a slow, solemn naturalistic style (the camera representing the cold stare of the non-abuser), which usually comes with no non-diegetic music and a jump cut sequence like so: breaking out supply/tapping arm/leaning back to enjoy fix, ecstatic gaping mouth optional...or, chaotic, first-person "rush" method of the Trainspotting and Requiem for a Dream music video mold, set to music or blaring sound effects. Either way, it's not an intellectual devise and is almost always distancing and boring: one of the best things about A Scanner Darkly is that you never see anyone using. What is interesting to watch is a character suffering the pangs of intense withdrawal, but that all depends on the actor.

Recovering Druggie Mom Movie Part 2. I'll clear something up: watching people do drugs is not aesthetically pleasing. It can be shot in a slow, solemn naturalistic style (the camera representing the cold stare of the non-abuser), which usually comes with no non-diegetic music and a jump cut sequence like so: breaking out supply/tapping arm/leaning back to enjoy fix, ecstatic gaping mouth optional...or, chaotic, first-person "rush" method of the Trainspotting and Requiem for a Dream music video mold, set to music or blaring sound effects. Either way, it's not an intellectual devise and is almost always distancing and boring: one of the best things about A Scanner Darkly is that you never see anyone using. What is interesting to watch is a character suffering the pangs of intense withdrawal, but that all depends on the actor.

Vera Farmiga, so underappreciated in Scorsese's The Departed, takes on the part of the recovering junkie by demonstrating why most people need to be high: their life is an intolerable plateau of non-occurrences. There are constant shots of her staring ahead, and she's looking at nothing, old age and beyond at the checkout line in a small town. When she asks her boyfriend/husband (never really clear) "Did you bring me something?" you feel that she's been looking forward to it all day, that it's what keeps her going. After she voluntarily gets off the junk, it's such a struggle to stay clean that when happiness actually comes her way, she's still only a nudge away from falling off the wagon for no good reason. She's a concentrating actress who collapses into herself and is eminently watchable. Unfortunately the movie betrays her with its constant cliches, making her anxieties a little too evident (lousy job! damn vacuum!) The material, not helped by the film's low budget, never challenges her as an actress.

1.30. E is for The Eel.

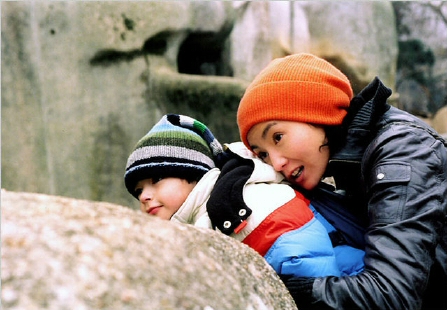

Of all the Japanese filmmakers obsessed with telling the story of women - Yasujuro Ozu, Kenji Mizoguchi, Seijun Suzuki in movies from his "spirit of sacrifice" period like Story of a Prostitute and Gate of Flesh - Shohei Imamura is the most successful, even though his best-known films (The Pornographers, Vengeance is Mine) don't deal directly with that theme. The Eel doesn't either, at least it doesn't set out to, starting with the story of a man who murders his wife after anonymous letters accusing her of infidelity lead him to discover her with another man. He's played by Koji Yakusho, the excellent Kiyoshi Kurosawa regular, and it's obvious how influential this film was on Kurosawa's Bright Future, a film about crime and life outside of prison which substitutes Imamura's title anguilliform with a jellyfish.

Yakusho starts over as a barber in a country town, where he saves a woman (Misa Shimizu) from suicide: her introduction is when the film starts moving into the territory of History of Postwar Japan as Told by a Bar Hostess and The Making of a Prostitute. Shimizu's character is involved in a bad relationship with a sniveling businessman who's after her mentally ill mother's money. When he starts getting into Shimizu's conflicted feelings about her inconvenient mom, her sexual relationship with the sleazy boyfriend, and her wholesome redemption as she's reborn through an infatuation with Yakusho, the film really finds itself. Centered around the two main characters with a number of recurring eccentrics (I would swear Sho Aikawa was part of the chorus, but he's not listed in the credits), Eel also reminded me a lot of Hal Hartley, particularly Henry Fool.

<<click here for 1/31/7 - 2/9/7>>

home about contact us featured writings years in review film productions

All rights reserved The Pink Smoke © 2009