2/10/7 - 2/22/7

john cribbs

In October 2006, Funderburg and Cribbs set out to watch at least 200 movies over the course of the next 200 days. They both watched a different slate of films and wrote about every single one; from epic high art masterpieces such as Max Ophul's The Earrings of Madame de... to lesser films by great directors like Richard Linklater's It's Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books to idiotic dreck like A Night at the Museum. The Pink Smoke is reprinting their writings about the puzzling experiment in cinematic endurance.

<<click here for 1/31/7 - 2/9/7>>

2.10. P is for Pickup on South Street.

Samuel Fuller's Pickup on South Street stands next to Stray Dog as my favorite location crime movie. In Pickup you can taste the cold beer Richard Widmark pulls up from the icy Hudson River in his shack off South Street, just like you can feel the oppressive Tokyo heat that bears down on a sweaty Toshiro Mifune as he follows the trail of the crook what swiped his firearm (the events of both films are set off by a pocket being picked on a crowded pubic transit). Pickpocketing is the tensest action to watch on film: in this and Bresson's Pickpocket (which was the original title of Fuller's film), the discreet thefts are nerve-racking to watch, although the cinematic approaches are entirely different. Here it's intimate, like Robert Ford bathing Jesse James in Fuller's first film, with three-time loser Widmark slowly fronting a busting-out Jean Peters.

Because it's Fuller, there's a sensational underlying issue involved: the threat of communism, portrayed as a kind of black mask villain that turns petty criminals into murderers. This angle doesn't turn the movie into some political hodge podge however: it's used as an apolitical plot devise the way a gangster movie might throw around the term "cosa nostra." Thelma Ritter, probably the greatest character actress of all time, gives what has to be one of the top 10 supporting performances as Moe the stoolie, whose death scene is grim and touching ("Look mister - I'm so tired, you'd be doing me a big favor if you just blew my head off..") Ritter knows the character so well, providing little moments of helplessness and fatigue between her street smarts. Among his filmography, Pickup may be Fuller's most realized and structurally pleasing effort - great looking transfer, of course. Criterion needs to release Park Row and White Dog next [remember, John: you should use this power only for good and never for evil - christopher funderburg].

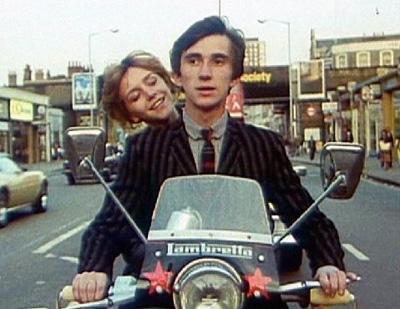

2.11. Q is for Quadrophenia.

Really, Quadrophenia isn't a rock opera the same way Tommy is? Oliver Reed will not be scream-singing in the background while Ann Margaret rolls around in a pool of beans spilling out of the television set? And Sting is not the star? For some reason I thought that both of these assertions were true, but then I used to confuse this movie with Quicksilver. I get confused. Anyway, it turns out the film was only inspired by the conceptual story behind the Who's album, a mods versus rockers drama, with the mods riding around in army parkas on Vespas with mirrors coming out the fronts like spider legs. Sting is a perfunctory rebel named Ace Face who really only pops up to dance, break a shop window, share a fag with the lead character in the back of a paddy wagon and ultimately sell out as a hotel bellboy ("BELL-BOY!")

Really, Quadrophenia isn't a rock opera the same way Tommy is? Oliver Reed will not be scream-singing in the background while Ann Margaret rolls around in a pool of beans spilling out of the television set? And Sting is not the star? For some reason I thought that both of these assertions were true, but then I used to confuse this movie with Quicksilver. I get confused. Anyway, it turns out the film was only inspired by the conceptual story behind the Who's album, a mods versus rockers drama, with the mods riding around in army parkas on Vespas with mirrors coming out the fronts like spider legs. Sting is a perfunctory rebel named Ace Face who really only pops up to dance, break a shop window, share a fag with the lead character in the back of a paddy wagon and ultimately sell out as a hotel bellboy ("BELL-BOY!")

The main kid is Jimmy Cooper, well played by Phil Daniels, an angsty and confused 1965 London answer to Jim Stark who seeks deliverance from his humdrum life of mixed up parents and boring day job: he learns too late that he's the only one who really takes his rebellion seriously. Very enjoyable, especially the big Briton riot scene (the new Bloc Party song "Waiting for the 718" may even possibly be referencing it), although a subplot involving a cute little blonde girl who's obviously in love with Jimmy is never resolved. Ray Winstone and Timothy Spall turn up in early roles, the Who appear on TV as the band Ready Steady Go! Also on a dvd documentary Sting refers to the simultaneous success of the Police and release of the film as "synchronicity" without a trace of irony.

2.12. R is for Reflections of Evil.

Made by Damon Packard (who used money he inherited when his grandmother died), Reflections of Evil is a feature length experimental narrative in the Kuchar brothers vein which intercuts stock footage of people in LA with scenes of Packard as Bobby, a progressively obese street watch salesman strung out on sugar (and apparently wanted for cookie theft) who's always making just enough to break even, unlike his successful nemesis Taffy Lewis. Shot on video and 16mm and entirely ADR'd, it's sprawling and thrown-togehter, so it's kind of amazing how much of it actually works. It has a handful of great scenes, including a run-in with a plainclothes cop ("Ever have a nigger come in your face?"), Bobby at the mercy of an "evil grandma" (a tribute to Packard's late granny?) and a flashback of young Steven Spielberg directing a movie on the Universal lot (the film's climactic scene takes place on the Schlinder's List Ride) which seems to use real Spielberg audio clips. There's a good amount of "found" material in the movie, including narration by Tony Curtis and the spirit of Klaus Kinski ranting onstage, which makes it all the more Kuchar-esque. As far as interesting, self-distributed oddities go, Packard's film (which gives special thanks to Sage Stallone??) is a head above the rest.

Made by Damon Packard (who used money he inherited when his grandmother died), Reflections of Evil is a feature length experimental narrative in the Kuchar brothers vein which intercuts stock footage of people in LA with scenes of Packard as Bobby, a progressively obese street watch salesman strung out on sugar (and apparently wanted for cookie theft) who's always making just enough to break even, unlike his successful nemesis Taffy Lewis. Shot on video and 16mm and entirely ADR'd, it's sprawling and thrown-togehter, so it's kind of amazing how much of it actually works. It has a handful of great scenes, including a run-in with a plainclothes cop ("Ever have a nigger come in your face?"), Bobby at the mercy of an "evil grandma" (a tribute to Packard's late granny?) and a flashback of young Steven Spielberg directing a movie on the Universal lot (the film's climactic scene takes place on the Schlinder's List Ride) which seems to use real Spielberg audio clips. There's a good amount of "found" material in the movie, including narration by Tony Curtis and the spirit of Klaus Kinski ranting onstage, which makes it all the more Kuchar-esque. As far as interesting, self-distributed oddities go, Packard's film (which gives special thanks to Sage Stallone??) is a head above the rest.

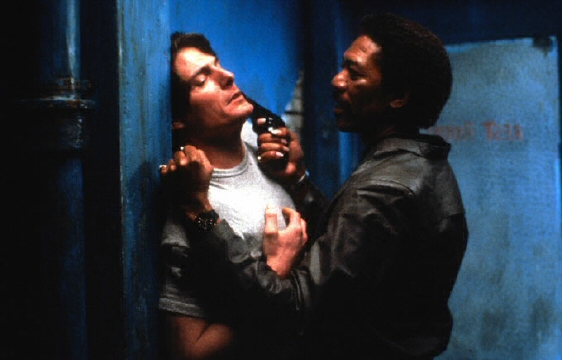

2.13. S is for Street Smart.

Street Smart is famous for being the movie everybody hates except for Morgan Freeman's Oscar-nominated breakout performance as a killer pimp. Based on that reputation - being an "intense Killer Pimp movie" - I have to say it's a letdown. Freeman does indeed play a stone cold pimp, on trial for accidentally murdering a john who was playing too hard with one of his bitches, but the film focuses more on the ethical crisis of reporter Christopher Reeve. To get a great story and reboot his fledging careet, Reeve, no better at approaching hardcore street hustlers than Iceberg Slim would be spinning around the earth to turn back time and save Margot Kidder, concocts a bullshit profile of a sugar daddy that everyone who knows Freeman assumes must be based on him. This seemed like the perfect Silent Partner-esque set up (p.s. The Silent Partner - now on dvd).

Unfortunately, much of what follows is the kind of fish out of water social comedy more akin to Crocodile Dundee, such as Freeman hilariously invited to a party of hopelessly shallow uptown yuppies. When the intrigue does come, in the form of helpful hooker Kathy Baker, it's too little too late. Reeve had that Will Smith thing going for him where he could basically get by on charm alone (although he went about it differently: less unhinged in-your-face goofiness, more dimply aw shucks modesty), so seeing him as a character becoming casually corrupted - first in his career, then his relationship, then his morality - should be an interesting change (he obviously thought so, allegedly only signing up for Superman IV: The Quest for Peace when the studio promised to finance Street Smart), but for some reason it's not very compelling.

Freeman is fine, but I'm so used to the go-to noble version of him from films that his scenes of intimidation are underwhelming (and he pales pimp-wise compared to Juan Fernandez's Duke from the J Lee Thompson classic Kinjite: Forbidden Subjects). I think what the film really needed was some kind of shocking and iconic scene, like Freeman treating Reeves like his bitch, forcing him to give him a blow job. As is, there doesn't seem to be any real (or fun) danger, mostly courtroom proceedings and a subpar subplot involving Reeve's infidelity against Mimi Rogers. Directed by Jerry "Scarecrow" Schatzberg, the "who???" auteur of the Lumière and Company anthology.

2.14. T is for Thank You For Smoking.

Without Aaron Echkhart, this movie would be utterly detestable. I mean worthy of being ripped apart by an angry mob. Well... it kind of is anyway. It takes the Lord of War approach to tobacco lobbyists, using that Libertine opening of the lead character telling us "You won't like me" but really meaning that we should like him because he's such a lovable misanthrope. It's one of those Election-style political movies where the unlikable/"likable" asshole narrates with smug confidence while the clever script goes to work setting up his life like a gum commercial from the 1950's. Going with the sloganesque quip "If you argue correctly, you're never wrong," the screenplay is a series of its dubious protagonist winning over reporters, talk show hosts, angry cancer patients (the "Cancer Boy" character is stolen from Bruce McCulloch in Brain Candy except here he's not funny) and Hollywood hot shots with his charming approach and manipulation of straight facts.

The writers of the movie are no Paddy Chayefsky - or Andrew Niccol for that matter - and have to rely on the movie's only weapon: Eckhardt, who succeeds in winning over the audience even as the alleged slickness of his character fails to convince. He's certainly the only actor in the movie to take his part seriously. Rob Lowe reprises his smarmy Wayne's World performance as a prima donna producer, Sam Elliot (of course) plays a dying, disgruntled Marlboro Man and William H. Macy fills in as the film's most obvious target, the anti-smoking politican. I'm sick of all the truth.com ads, but I actually prefer them to this send-up of those who would use the cigarette issue for political gain. And the film wouldn't be complete with its broad media punching bag, personified (term used loosely) by Katie Holmes, who seduces Eckhardt (aren't there any appealing actresses to match their charimatic leading men these days??) then betrays him in an expose. Huh? What year is this? The young female reporter uses her feminine wiles (what little are on display) to in term fuck over her subject? I may be giving away a lot of the plot, but that's because I don't want anyone anywhere to see this movie. Disgraceful.

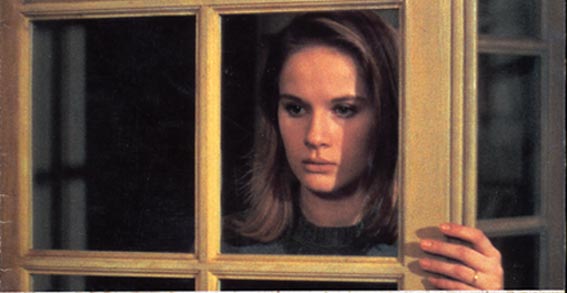

2.15. U is for Une Femme Douce.

I realize I'm cheating a little here, but I couldn't come up with any appealing "U" movies. I thought about revisiting Emir Kusturica's Underground, but got worried that I'd somehow accidentally end up seeing The Underground Comedy Movie again. Chronicling the marriage of a pawnbroker and his young wife, Une Femme Douce is the earlier sister film of Bresson's masterpiece L'Argent. Both films deal with casual dehumanization, specifically through the handling of money as depicted by his trademark three-step action of opening a drawer, removing bills and passing them to an obscured party. These series of events – determining what something is worth and shelling out paper – never changes, and Bresson stylizes an inescapable world of commerce where the routine of getting money, spending money and counting money serves as spirit crippling sameness.

The spirit affected here is Dominique Sandra's "gentle" wife, whose suicide from the window of her apartment bookends the film. Like its follow-up Four Nights of a Dreamer, Femme is from a Dostoevsky short ("A Gentle Creature"), L'Argent from Tolstoy ("The Forged Coupon"), and though each is a more successful adaptation than his attempt at Diderot (the hugely disappointing Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne), Femme only touches the surfaces of the story's themes of humble Christianity and L'Argent feels more Dostoevsky than Tolstoy. The director's underplayed, structurally flawless approach (an obvious influence on more recent filmmakers like Michael Haneke and Claire Denis) consists of characters sitting down, standing up, touching furniture, the purposely hidden face of Sandra's alleged lover, the shuffle of feet, sexual discomfort in the separating of knees, actor's stoicism (they're only heard laughing off screen or under a blanket) the bracing sound of doors opening and closing, the cars on the street – it's surprising that he includes of moment of Ozu-like decisive action as the heroine breaks down and cries.

Sandra, oppressed by a monetary society and the growing inequality of her marriage, seems to her husband to be suffering from a mysterious malaise like the women of Red Desert and Safe, not recognizing his own insensitivity as material cause. Despite New Yorker's difficult-to-follow video copy (the guy in charge of their subtitles is Une Homme Douche), Bresson's painterly use of color enriches the texture of his characters' emotional environment: after this, his first color film, he really could do no wrong – Pickpocket and A Man Escaped are good, but the lack of pictorial excess is almost romanticized by their black and white cinematography. With color, Bresson discovered the majestic tranquility of the mundane that his career had been leading to, informing the classic Godard quote, "Robert Bresson is French cinema, as Dostoevsky is the Russian novel and Mozart is German music."

2.16. V is for Valerie and Her Week of Wonders.

If Jodoworsky had made a Hammer horror movie, this is what it would have ended up looking like, but it's not quite as cool as it sounds. Less a movie than an excuse for the director to fuck all his nymphets (what Euro-nudie pic isn't?), this Czechoslovakian orgy of stick-white vampires and lecherous priests in a small village is hugely irritating, like a party you came to with a friend and just want to leave but you can't because a bunch of nuns are dancing around blocking the entrance. I really don't have much to say about it beyond the obligatory plot summary: young girl experiences her first menstruation, triggering a series of interlocking dreams about lustful vampires who prey upon her youth. The loss of a pair of dangling bell earrings bring on the sexual explosion of events (hm – wonder why) and

I don't know, stuff happens. Mostly involving cleavage. Sort of Ken Russell-lite for dummies, with symbolic sexual imagery that would be done better in films like The Company of Wolves.

It's theoretically cool, but just sort of brainless in execution, like everyone showed up in costume and the director (Jaromil Jires) had to think up some crazy shit to take place in pastoral landscapes and bad sets of crypts filled with fake spider webs. That's not the case, it's based on a classic Czech novel apparently, but to Jires' intentions, besides being hopelessly dated, are detrimental to what the film's trying to say about the innocent sexual awakening of a young girl. His fetishistic camera kicks and whirls to no lasting effect. The one thing that can be said for the movie is the look of the master vampire and the androgynous fusion of brother and sister seem to have influenced Japanimation classics like Vampire Hunter D and Ghost in the Shell, but who the hell knows if it actually did. I mean, is Mamoru Oshii sitting around watching movies like this? It was just a washout: I didn't have any interest in sitting through it when it started, and the fact that I did just made me kind of angry at myself. I guess there's an audience for this kind of thing, but when you come down to it, it's just dumb. Man, I'm in a bad mood. I should have just rented Vice Versa, or Victory.

2.17. W is for Warm Water Under a Red Bridge.

Imamura's last film, reuniting him with the stars of The Eel, sets up an even stranger concept than that previous film. Prompted by a deceased homeless man's abstract mission to find a golden Buddha, Koji Yakusho travels to a small fishing village where he meets Misa Shimizu. Shimizu suffers from an anatomical oddity: her body fills up with water, and she can only flush herself by doing something "wicked." He's coaxed into regular rough sex with her that ends in a literal geyser of orgasm, the expelled water seeping to the stream below and replenishing the wading fish (the title becoming therefore literal and figurative). The director fashions from this unique plot an intimate drama-comedy, which of course plays to the absurdity of the set-up (the musical score, for one thing, is an interesting decision).

Imamura's last film, reuniting him with the stars of The Eel, sets up an even stranger concept than that previous film. Prompted by a deceased homeless man's abstract mission to find a golden Buddha, Koji Yakusho travels to a small fishing village where he meets Misa Shimizu. Shimizu suffers from an anatomical oddity: her body fills up with water, and she can only flush herself by doing something "wicked." He's coaxed into regular rough sex with her that ends in a literal geyser of orgasm, the expelled water seeping to the stream below and replenishing the wading fish (the title becoming therefore literal and figurative). The director fashions from this unique plot an intimate drama-comedy, which of course plays to the absurdity of the set-up (the musical score, for one thing, is an interesting decision).

In his later films, Imamura became a master of presenting many random things that are all somehow connected. In Water, Shimizu's strange condition, Cherenkov light, cadmium poisoning, a senile grandmother, seedy pornographers, fishing, unemployment, homelessness and a bizarre space womb dream sequence all factor in to the larger scheme of things. From their correlation Imamura contrasts the excitement of new love vs. long term relationships that dry up, kinky sex vs. the curse of sexuality, nature vs. industry, fertility vs. desiccated old age. When I mentioned Imamura's understanding of women in the earlier Eel write-up, I didn't mean to suggest that he made movies with women as thematic centerpieces (that's for Antonioni to do). But Eel and Warm Water (and the earlier films I mentioned before) reveal an awareness of feminine anxieties in terms of society and physicality that feel just sort of naturally perceptive, all the more so since both movies are from the viewpoint of a male protagonist. This film nails certain scenes on the head and misses others, but is always – like any Imamura movie – expertly handled and strangely poignant.

2.18. X is for Xanadu.

I know – the flaw with this concept (watching one film for every letter of the alphabet) is that there are very few "X" titles to choose from, as I've seen the first two X-Men movies and X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes several times. But since this one is largely considered Gene Kelly's best musical (or at least the most popular musical to feature Olivia Newton-John), I thought it was worth checking out. Maybe not "worth" checking out but I figured the running time was at least short enough. What we have here is Swan from The Warriors (in his words: "The Warriors opened a lot of doors for me which Xanadu then closed"), who brings to life a mysterious girl on roller skates he can never catch up with until he brilliantly decides to put on some skates himself. What's missing already is a team of government scientists and agents led by Peter Coyote trying to capture the phantom skater for their own nefarious ends: what kind of 80's movie is this? Instead, Swan hooks up with Kelly (always classy, even when he's carted out for shit like this, sadly but with good reason his last film) to ill-advisedly open a roller disco at the beginning of the 1980's. The movie ends with the title club's opening, so there isn't an extra Don Bluth animated sequence to show its miserable failure.

Co-produced by Joel Silver (it's funny how all those 80's & 90's testosterone-based mega-producers got started in soft music-themed movies like this, Flashdance and Playing for Keeps), Xanadu has songs by the Grease guy and ELO's Jeff Lynne, and features the incredibly confusing tagline "Open your eyes and hear the magic" (?) There's not much to say: the movie's obviously a living joke (a poster for the new Broadway adaptation Xanadu: The Musical features the tagline "No, really") that exists somewhere between and shares the most unfortunate aspects of two really embarrassing moments in American pop culture (think The Wiz meets Staying Alive). I thought it might be interesting to check and see if Orson Welles dies in 1980, the way Charles Foster Kane died at his own personal Xanadu, but he outlived this flop by five years.

2.19. The Phantom Carriage.

I have to say, I didn't get this movie. If the Jedi are so powerful, why can't they sense the evil emperor hiding in their midst? Why doesn't Darth Vader remember building C3-P0 as a child in the "later" movies? And what the hell is a "midi-chlorian?" Oh wait - this is not a shitty Star Wars prequel, this is actually an excellent Swedish silent film about fate and redemption directed by and starring Victor Sjostrom (best known as the lead in Ingmar Bergman's Wild Strawberries). It's sort of a play on A Christmas Carol, and also a precursor to Bergman's The Seventh Seal, that's based on a myth that the last person to die before the start of the new year is cursed to drive the phantom carriage, picking up souls of the dead and driving them to the afterlife.

I have to say, I didn't get this movie. If the Jedi are so powerful, why can't they sense the evil emperor hiding in their midst? Why doesn't Darth Vader remember building C3-P0 as a child in the "later" movies? And what the hell is a "midi-chlorian?" Oh wait - this is not a shitty Star Wars prequel, this is actually an excellent Swedish silent film about fate and redemption directed by and starring Victor Sjostrom (best known as the lead in Ingmar Bergman's Wild Strawberries). It's sort of a play on A Christmas Carol, and also a precursor to Bergman's The Seventh Seal, that's based on a myth that the last person to die before the start of the new year is cursed to drive the phantom carriage, picking up souls of the dead and driving them to the afterlife.

Sjostrom plays an unrepentant, forcibly repugnant sinner - "lips stained with wickedness" - who, upon dying just before midnight on New Year's Eve and learning that he is fated to take up the mantle of the carriage coachman, is taken back to see what a bastard he's been (of course, he gets a chance to set it all right). The superimposition effects are top notch (come to think of it, fuck the Star Wars prequels!), especially in a sequence where the coach goes out to see to pick up a drowning man. The performances, considering they are subject to the usual silent film overacting, are surprisingly subtle and moving, especially those of Sjostrom and Astrid Hold from Haxan. I didn't have as personal a connection with the film as Funderburg, but it was a marvellous experience to get a chance to see it on the big screen, especially with excellent live piano accompaniment.

2.20. Y is for Yi Yi.

There's a really fantastic small moment in Yi Yi: NJ, a family man who's been fatalistically reunited with the love of his youth, has innocently (or not) met with her in Japan during a business trip. As they stand at a train station in long shot, she gently pulls him away from the edge further from the path of the tracks. Especially now, seven years after the movie's release, in the wake of so many false moments from stillborn creations like The Life Aquatic and the sentimental pandering of "fun" movies about families like Little Miss Sunshine, Edward Yang's film is a matchless masterpiece, a distinctive symbiosis of Ozu storytelling and Renoir characterization. He puts so much between the three hour film's opening wedding and closing funeral – birth, murder, attempted suicide, the near collapse of more than one family and relationship, the maturation of a teenage girl and the innocent philosophies of her kid brother – that it flirts with bloated melodrama. So it says a lot for Yang that the film moves between its characters and storylines seamlessly in expertly constructed long takes and beautiful bright cinematography.

Centered around a middle class Taiwanese clan living in an apartment in Taipei, the film opens with them together at the marriage of the children's troublesome uncle, breaks them up into their separate experiences, and brings them back together after the death of someone close to them. Their relationships with each other and extended relationships with the people in their lives, from NJ's former flame to a stranger his son Yang-Yang meets in front of the elevator of their building, are basis for a series of discoveries, disappointments, reaffirmations and connections. Considering its static shots and running time, none of this is ever boring. Even more impressive is the film's understanding of kids: Yang-Yang is a surrogate for the director, using his camera to shoot the back of people’s heads "so they can see" as Yang uses his camera to capture life moments often missed, like the gentle touch at the train station. Yi Yi is a movie you live in, go crazy for (unless you're Paul Cooney) and want to revisit.

2.22. Z is for Zodiac.

The elusive Zodiac, in the wake of the fairly recent arrests of the Green River and BTK killers, is the closet thing America has to a Jack the Ripper, so it makes sense that David Fincher and Warner Brothers would seek to recreate the pop mythology surrounding the publicity-seeking terrorist of the late 60's Bay Area. And this kind of movie is exactly what the killer would have reveled in: his "achievements" dug up and turned over and cross-analyzed under Fincher's detailed camera, which is more interested in a faithful reenactment of the murders than making them particularly horrifying, even staging some of the more controversial crimes which the killer may or may not have committed more ambiguously, as Spike Lee did in his "criminally" underrated Summer of Sam. To this effect, Fincher has several different actors portray the Zodiac (none of them the same actors who later play suspects). The movie is interesting because of this deliberate elusiveness, but that's also its main problem: there are so many blind alleys that, structurally, everything becomes anti-suspenseful.

For example, there are at least three scenes that are set up like something dangerous is about to happen, and when they don't (by sheer virtue of the face that, historically, they didn't), the set-up feels like a haunted house trick that isn't paid off. In keeping with true events, the man who called to speak with Melvin Belli on the talk show is not the killer, and the heavy-breathing calls to Robert Graysmith are as ambiguous as they would be if an excited Robert Opel were phoning after successfully streaking the Academy Awards.

Although the film, like the two Graysmith books it's based on, leans largely towards convicted child molester Arthur Lee Allen as a Zodiac suspect, its conclusions after compiling a series of eerie yet useless coincidental evidence are less interesting than the effect investigating them has on its lead characters, something the film has in common with Bong Joon-ho's superior Memories of Murder (also based on true events, and also ending without resolution). The high-def photography by Gus Van Sant's gifted cameraman Harris Savides is revolutionary, creating the first feature HD film that's just as gorgeous to take in as anything shot on 35mm: the detailed murders in particular are ghastly beautiful, as are the several "research montages" in which cabinets are opened, files are stacked, pages are turned and scrutinized, and behind the eyes the mind kicks up whirlwinds of obsessive finding in congruence with the excited breathing of the murderer. It's here that the movie finds itself, in the compulsive throes of deliberate human procedure.

<<click here for 2/23/7 - 3/1/7>>

home about contact us featured writings years in review film productions

All rights reserved The Pink Smoke © 2009