4/1/7 - 4/10/7

john cribbs

In October 2006, Funderburg and Cribbs set out to watch at least 200 movies over the course of the next 200 days. They both watched a different slate of films and wrote about every single one; from consensus classics such as Anthony Mann's The Naked Spur to lesser films by great directors like Claude Chabrol's Innocents with Dirty Hands to idiotic dreck like Rollergator. The Pink Smoke is reprinting their writings about the seemingly endless experiment in cinematic endurance.

<<click here for 3/22 - 3/31>>

4.1. 5x2.

Francois Ozon's filmography is very frustrating. After the languid misfires Swimming Pool and 8 Women, it was easy enough to attribute the 1997 masterpiece See the Sea to co-author/star Marina de Van, whose In My Skin was in the same unique, sinister style of that film. But here we have another masterfully constructed feature written and directed by Ozon, a consolidation of ideas on why relationships don't work, that is sad and visionary. This is a beautiful, human story, the kind of delving character drama that films filled with dopey, dodging insincerity like 9 Songs or Eternal Sunshine could never be. It stars Valerie Bruni-Tedeschi (whose unmistakable, soft, vulnerable voice I last heard in Color of Lies) and Stephane Freiss as a couple who divorce, experience parenthood, have a baby, get married, and meet, in that order. Borrowing themes and ideas from Harold Pinter's Betrayal and Noel Coward's Private Lives (but never stealing from either), 5x2 is about what the couple needs from each other and what they end up getting; how happiness with another person - even at the height of contentment, like a wedding day - is unattainable for these people. In that respect, it's almost like a less horror-film version of Irreversible (both films technically have a happy ending), where it doesn't take some tragic outside event to destroy the idealism of being together.

Water Drops on Burning Rocks.

Ozon obviously considers himself a Fassbinder disciple, a good case for that

speculation being this adaptation of one of RWF's early plays. The original must

have been a dress rehearsal for future projects: the screenplay, about three

people falling under the spell of a manipulative fiend, is an amalgam of several

well-known Fassbinder films, including In a Year with 13 Moons, Fox

and His Friends, Martha and The Bitter Tears of Petra von

Kant. Ozon leaves the film stylistically dull (with the exception of a

surreal musical number, the kind Fassbinder used to lift from Godard) and

doesn't add much of his own filmmaking personality. Apart from the always

watchable Ludivine Sagnier, the bubbly Lolita of Swimming Pool, there's

little attractive about this half-assed experiment in auteur revisioning - Todd

Haynes did it better with Far from Heaven.

Ozon obviously considers himself a Fassbinder disciple, a good case for that

speculation being this adaptation of one of RWF's early plays. The original must

have been a dress rehearsal for future projects: the screenplay, about three

people falling under the spell of a manipulative fiend, is an amalgam of several

well-known Fassbinder films, including In a Year with 13 Moons, Fox

and His Friends, Martha and The Bitter Tears of Petra von

Kant. Ozon leaves the film stylistically dull (with the exception of a

surreal musical number, the kind Fassbinder used to lift from Godard) and

doesn't add much of his own filmmaking personality. Apart from the always

watchable Ludivine Sagnier, the bubbly Lolita of Swimming Pool, there's

little attractive about this half-assed experiment in auteur revisioning - Todd

Haynes did it better with Far from Heaven.

Sitcom.

Ozon hops from Fassbinder to Pasolini territory, tearing down the moral pillars of an

upper-middle classic family and their maid, Teorema's liberator/demon

Terrence Stamp replaced here by a scarlet-eyed rat. But unlike Pasolini's

novel/film, this movie plays its themes loosely, the result being broad excess

comedy in the John Waters vein that does feel painfully like some sort of

standard - albeit depraved - sitcom. Not much investment is required, nor

rewarded: instead of saying anything about the taboos it brings up, or parodying

the shameful proclivities inside a family structure, like Happiness of the

Katakuris for example, Sitcom just keeps hitting you over a head with

a folded newspaper until you wish it would go away. This was Ozon's re-teaming

with Sea's Marina de Van, and her presence onscreen is never anything but

captivating - I just wish the film was more like the poster's image of de Van on

her belly with a knife in her mouth slinking creepily forward. And so I remain

frustrated with Ozon and his notable triumphs buried beneath severe

near-misses...

Ozon hops from Fassbinder to Pasolini territory, tearing down the moral pillars of an

upper-middle classic family and their maid, Teorema's liberator/demon

Terrence Stamp replaced here by a scarlet-eyed rat. But unlike Pasolini's

novel/film, this movie plays its themes loosely, the result being broad excess

comedy in the John Waters vein that does feel painfully like some sort of

standard - albeit depraved - sitcom. Not much investment is required, nor

rewarded: instead of saying anything about the taboos it brings up, or parodying

the shameful proclivities inside a family structure, like Happiness of the

Katakuris for example, Sitcom just keeps hitting you over a head with

a folded newspaper until you wish it would go away. This was Ozon's re-teaming

with Sea's Marina de Van, and her presence onscreen is never anything but

captivating - I just wish the film was more like the poster's image of de Van on

her belly with a knife in her mouth slinking creepily forward. And so I remain

frustrated with Ozon and his notable triumphs buried beneath severe

near-misses...

4.2. Tropical Malady.

Tropical Malady switches gears in an extreme fashion mid-movie: it goes from being an observational romance to a subdued version of Ken Russell's Princess Mononoke. Apichatpong Weerasethakul drags his audience through shoe stores, movie theaters, and public buses, the slow pace meant to bleed out any sense of mystery and magic in these everyday locations. The problem is that once he's retreated into the jungle, the pace remains langurous, and what would be an atypical fantasy film gives itself over to self-indulgent assessments of how mythology informs modern human behavior. The love affair at the center of the film is also creepy, and the rare supernatural moments are outweighed by the director's aversion to any sort of dramatic storytelling.

Tape.

This is the "other" Richard Linklater that came out the same year as Waking Life, a dv minimalist

piece adapted by Stephen Belber from his play, with three characters in a

Lansing, Michigan hotel room, played out in real time (just under an hour and a

half). It feels a little like small movie Soderbergh territory, or a blue collar

Rashomon, but with a fresh atmosphere that's more or less given over to

the actors. Three old high school friends confront, accuse, and belittle each

other to the breaking point, and by the end of the movie it still isn't 100

percent clear what's true, or which reactions and allegations were based on

control. The dialogue courses from one layer of resentment to another, never

revealing anything conclusive - it's a relief from the swinging from

vine-to-vine writing style of the Before Sun movies. Uma Thurman has an

amazing line to Robert Sean Leonard near the end of the film that is absolutely

searing. Some of the shot decisions work, others seem desperate to relieve the

stasis of the location (it's very cutty) but overall Linklater tells the story

more intensely on "tape" than anyone else probably could have on

film.

This is the "other" Richard Linklater that came out the same year as Waking Life, a dv minimalist

piece adapted by Stephen Belber from his play, with three characters in a

Lansing, Michigan hotel room, played out in real time (just under an hour and a

half). It feels a little like small movie Soderbergh territory, or a blue collar

Rashomon, but with a fresh atmosphere that's more or less given over to

the actors. Three old high school friends confront, accuse, and belittle each

other to the breaking point, and by the end of the movie it still isn't 100

percent clear what's true, or which reactions and allegations were based on

control. The dialogue courses from one layer of resentment to another, never

revealing anything conclusive - it's a relief from the swinging from

vine-to-vine writing style of the Before Sun movies. Uma Thurman has an

amazing line to Robert Sean Leonard near the end of the film that is absolutely

searing. Some of the shot decisions work, others seem desperate to relieve the

stasis of the location (it's very cutty) but overall Linklater tells the story

more intensely on "tape" than anyone else probably could have on

film.

4.3. Story of a Prostitute.

Somewhere I read that this was Suzuki's favorite of his titantic oeuvre, which makes sense. A lot of renowned male filmmakers - Bresson, Dreyer, Godard, Von Trier, Wong Kar-Wai - seem overly fond of their stories of women, presumably because it gives them a chance to demonstate how well they understand their heroines. Harumi, the titular madam of the film, is unlike the female subjects of those directors in that she isn't at all likable: she's loud and bratty from the start, and her selfish decisions pretty much doom Mikami, her male companion. Her stubborn (and high-pitched) form of rebellion my be a cry against fascism, but it's played achingly serious. After being brought to a military mountain town with a group of girls, she's targeted for torture by a possessive adjutant who sounds like Toshiro Mifune but looks like Mr. Fuji: in one typically wild Suzuki shot, she imagines him magically torn to pieces. Mikami, the adjutant's assistant, becomes enamored of her despite his strict sense of duty to the empire (and, by proxy, the adjutant), which Harumi works to dissolve after he slaps her hard across the face and she falls helplessly in love with him. The themes are Kunderian - political oppression leads to sexual domination and disorientation - and it's the saultriest pre-Oshima Japanese film this side of Onibaba...unfortunately, it's hard to care for the weak and whiny characters, or to have a good time with the heavy-handed melodrama.

4.4. Fighting Elegy.

On the other hand, there's plenty of fun to be had with Fighting Elegy, which has the privilege of containing some of the most conservative masturbation jokes I've ever seen. Here Suzuki tackles the same ideas as in Prostitute - fascistic, militaristic corruption of the individual spirit - but does so through a series of broad vignettes and hilarious proverbs like "All dealings with sissies are forbidden!" Hideki Takahashi is brilliant (although he's the oldest looking high schooler in film history) as Kiroku, whose healthy, human, adolescent yearing for the Catholic daughter of his landlord conflicts with the robotic sense of masculinity instilled in him by his paramilitary gang buddies. In that sense, it's almost a better and more relevant version of Fight Club (and believe me, I'm getting tired of saying that) in which he resorts to nationalist machismo as an outlet for his pent-up sexual frustrations. After an hour of goofy humor, the film turns unexpectedly serious as it correlates Kiroku's development with the rise of imperialism in Japan and reveals itself as a sharp, seditious satire. Why can't American comedies be socially and historically relevant? I mean, besides History of the World Part I.

4.5. Youth of the Beast.

It's embarrassing to admit it, but I think I prefer my Suzuki slick, simple, and whorishly stylistic. His yakuza movies made him a more openly-experimental contemporary to Melville and the elusively-titled Youth of the Beast is almost as good as Branded to Kill. Sort of his take on the much-visited Red Harvest storyline, Beast is about a former cop who sets to avenge the death of a fellow officer by playing two crime factions against each other. Jo Shisido - a forerunner to Chow Yun Fat's baby-faced tough guy - is awesome in the lead, squaring off against multiple goons, including a sociopath who pulls a razor from his sock and goes to work on anyone who calls his mother a "whore." Some classic Suzuki tricks include characters observing a club through a two-way mirror, his patented black-and-white/sepia-colored jump, a junkie chasing a super-imposed ghost straight down a stairway, and a torture scene played out against a glass window. Those props notwithstanding, it's easily the least risky of any of his movies I've seen, but highly entertaining despite its straight-forwardness.

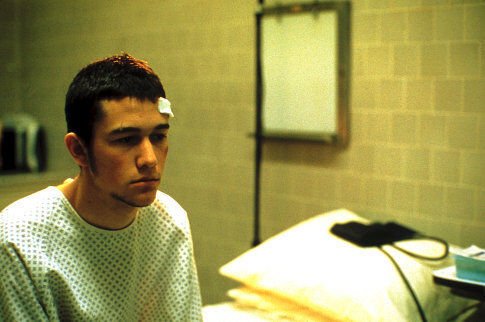

4.6. Manic.

There's no wrong way to shoot Zooey Deschanel: you could dive into her eyes onscreen and be lost in them

indefinitely. Those eyes completely overshadow this Kids Flew Over the

Cuckoo's Nest, which focuses on a group of troubled teenagers in a mental

institution without a Freddy Kruger to kindly dispatch them. They fight on the

basketball court, throw furniture, look at the floor instead of well-meaning

social worker Don Cheadle, stage impromptu mosh pits, get weird visits from

step-parents and refuse to be understood, but they're all basically text book

examples with no background. Even as it critiques institutional healing, the

movie can't help but psychologize its characters (abusive dad = abusive son),

and not well: a kid who's into Slipknot suddenly reading The Myth of

Sisyphus is just not convincing. The only other stand-out is a fine leading

performance by Joseph Gordon-Levitt, but he's much better in Brick. Some

of the music is by Thurston Moore.

There's no wrong way to shoot Zooey Deschanel: you could dive into her eyes onscreen and be lost in them

indefinitely. Those eyes completely overshadow this Kids Flew Over the

Cuckoo's Nest, which focuses on a group of troubled teenagers in a mental

institution without a Freddy Kruger to kindly dispatch them. They fight on the

basketball court, throw furniture, look at the floor instead of well-meaning

social worker Don Cheadle, stage impromptu mosh pits, get weird visits from

step-parents and refuse to be understood, but they're all basically text book

examples with no background. Even as it critiques institutional healing, the

movie can't help but psychologize its characters (abusive dad = abusive son),

and not well: a kid who's into Slipknot suddenly reading The Myth of

Sisyphus is just not convincing. The only other stand-out is a fine leading

performance by Joseph Gordon-Levitt, but he's much better in Brick. Some

of the music is by Thurston Moore.

X-Men: The Last Stand.

Brett Ratner said in a recent interview that Professor X is like Martin Luther King and Magneto is like Malcolm X (even though Professor X

and Malcolm X share the same last name.) I guess that means Rogue doesn't want

to be black anymore? This step back in the evolution of the series makes some

shockingly bad decisions, cramming the highly-regarded Dark Phoenix story into a

movie with plenty going on already being the most blatant. Jean Grey resurrects

and stands around looking menacing until the end of the movie, where she has an

anti-climatic showdown with (who else?) Wolverine (a shirtless Hugh Jackman

holding the corpse of the woman he loves, who he just killed? Little familiar -

wasn't that the end of Van Helsing?) Jackman also said in an interview

that he thinks Wolverine merits his own movie. He's had THREE! Apparently

the other heroes are so disposal, in some cases they aren't even dignified with

a conclusive death scene. The good ideas that do exist - Kitty Pryde unable to

phase when she's near the power-saping kid, Jamie Madrox tricking the satellite

video - are small, whereas the problems are Juggernaut-sized: making the Phoenix

entity a split-personality, wasting time on Ben Foster's Angel, recasting Halle

Berry, having Rogue pick the cure... Did Bryan Singer spoil us all with

X2?

Brett Ratner said in a recent interview that Professor X is like Martin Luther King and Magneto is like Malcolm X (even though Professor X

and Malcolm X share the same last name.) I guess that means Rogue doesn't want

to be black anymore? This step back in the evolution of the series makes some

shockingly bad decisions, cramming the highly-regarded Dark Phoenix story into a

movie with plenty going on already being the most blatant. Jean Grey resurrects

and stands around looking menacing until the end of the movie, where she has an

anti-climatic showdown with (who else?) Wolverine (a shirtless Hugh Jackman

holding the corpse of the woman he loves, who he just killed? Little familiar -

wasn't that the end of Van Helsing?) Jackman also said in an interview

that he thinks Wolverine merits his own movie. He's had THREE! Apparently

the other heroes are so disposal, in some cases they aren't even dignified with

a conclusive death scene. The good ideas that do exist - Kitty Pryde unable to

phase when she's near the power-saping kid, Jamie Madrox tricking the satellite

video - are small, whereas the problems are Juggernaut-sized: making the Phoenix

entity a split-personality, wasting time on Ben Foster's Angel, recasting Halle

Berry, having Rogue pick the cure... Did Bryan Singer spoil us all with

X2?

4.7. The Naked Spur.

Anthony Mann and Jimmy Stewart may have been an even more important paring in Western cinema than Ford and Wayne: their series of psychological melodramas are haunting character studies, The Naked Spur being arguably the most well known and yet the only one not currently available on disc (I just stopped myself, looked on amazon, and now feel like an ass - it's coming out this summer. Quick check: O Lucky Man? No such luck.) Anyway...it's not the masterpiece (that's between Bend of the River and Winchester '73), but it's not one of the lesser efforts either (that would be the later Far Country and The Man from Laramie) and overall it's pretty great. Like most great westerns, it's about the journey, in this case the cross-country transportation of a wanted crook by three men who are slowly starting to turn against each other. Ralph Meeker replaces Arthur Kennedy as the shady, unstable cad, Millard Mitchell has the Walter Huston role, and Robert Ryan never looked so unkemptly sexy as the alleged murderer they're bringing in. Janet Leigh's thrown into the mix, but the movie belongs to Stewart and his tortured Howard Kemp, trying to regain his idealistic pre-war life by sinking further into becoming a desperate crackpot (nobody can bark "Ah, shut up!" with the same fevered urgency.) I'm glad this is being released on dvd, as the cropped editing on the old vhs copy is atrocious and doesn't do justice to Mann's Rocky Mountains.

4.8. The Piano Tuner of Earthquakes.

Following Institutee Benjamenta, the Brothers Quay

have tried their hand at another live action feature film, and this one is an

underwhelming failure. Rather than conjure the kind of strange, fabulist fantasy

that distinguishes their short films, Piano Tuner is a glossy-framed case

of apparent disinterest on the part of the filmmakers and executive producer

Terry Gilliam, whose cold streak continues. It's always cool to see Gottfried

John (filling in for David Warner) but everyone in the cast sleepwalks through

pretty but uninspired sets, dehumanized in a useless painting like characters

from a Guy Maddin movie. It's hard to pinpoint what would have improved the

film, but that may be the problem: a disappointing lack of innovation that

renders the movie at times hopelessly cheesy and overall dismissible.

Following Institutee Benjamenta, the Brothers Quay

have tried their hand at another live action feature film, and this one is an

underwhelming failure. Rather than conjure the kind of strange, fabulist fantasy

that distinguishes their short films, Piano Tuner is a glossy-framed case

of apparent disinterest on the part of the filmmakers and executive producer

Terry Gilliam, whose cold streak continues. It's always cool to see Gottfried

John (filling in for David Warner) but everyone in the cast sleepwalks through

pretty but uninspired sets, dehumanized in a useless painting like characters

from a Guy Maddin movie. It's hard to pinpoint what would have improved the

film, but that may be the problem: a disappointing lack of innovation that

renders the movie at times hopelessly cheesy and overall dismissible.

Phantom of the Opera.

There's no project Joel Schumacher hasn't managed to gay up by 75% but it's shocking that he was able to take an already fairly-flamboyant Broadway

musical and make it seem even fruitier. Schumacher is credited with co-writing

the screenplay, but the only thing he seems to have added is a lame swordfight

and useless flash-forwards (in black and white no less.) At best, the movie

looks like a cheap music video. The dead girl from Mystic River and

Dracula 2000 (who is also Beowulf in the unsurpassed Beowulf and

Grendel*) have terrible singing voices and even less on-screen chemisty,

and the less said about Minnie Driver the better...but not as fun: she's

awful! Even for this project, her performance is ridiculous. Schumacher must

have been dreaming of Bat Nipples to not put a stop to it. Poor Miranda

Richardson is surrounded by amateurs and subjected to a retarded flashback which

unconvincingly connects her character to the villain.

There's no project Joel Schumacher hasn't managed to gay up by 75% but it's shocking that he was able to take an already fairly-flamboyant Broadway

musical and make it seem even fruitier. Schumacher is credited with co-writing

the screenplay, but the only thing he seems to have added is a lame swordfight

and useless flash-forwards (in black and white no less.) At best, the movie

looks like a cheap music video. The dead girl from Mystic River and

Dracula 2000 (who is also Beowulf in the unsurpassed Beowulf and

Grendel*) have terrible singing voices and even less on-screen chemisty,

and the less said about Minnie Driver the better...but not as fun: she's

awful! Even for this project, her performance is ridiculous. Schumacher must

have been dreaming of Bat Nipples to not put a stop to it. Poor Miranda

Richardson is surrounded by amateurs and subjected to a retarded flashback which

unconvincingly connects her character to the villain.

* The still-unremarkable Gerard Butler -- 2010 John.

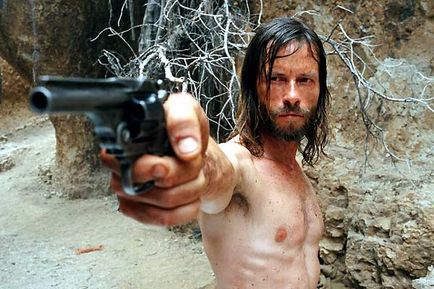

4.9. The Proposition.

Ever since Quigley Down Under, the world has been impatient for an aboriginal western of the same caliber. There's not much "aboriginal" about The Proposition (not to be confused with the Patrick Bergin/Theresa Russell classic) which, like Quigley, deals with the genocide of natives down under. As the screenplay is by Nick Cave, I was worried it might be humorless and overly spiritual, but the material's fine, it's just not handled all that well. There's a lot of rote imagery and plotted action that stall the film from being as exceptional an experience as Dead Man, its most obvious influence. Somehow, it doesn't reach the supernatural surrealism of Jarmusch's film, even with the advantage of color to pronounce its goriness (Benoit Delhomme's cinematography does look great). The cast - Emily Watson, Danny Huston, David Wenham - are excellent, especially Ray Winstone, who is treated more of a main character in the movie than the broody Guy Pearace, and the legendary John Hurt, who should have a country named after him or something. Noah Taylor is again oddly relegated to a two-second part.

4.19. May.

May is my kind of macabre. Its horror is integrated with the intangible desire to escape an isolation wrought from a fucked-up childhood and consequential social ineptitude. Like Romero's Martin, May is a modern social monster, but a reluctant one who doesn't necessarily romanticize her morbid propensities. It's more that she's idealized the people in her life and is subject to dull frustration (or "doll" frustration) when they don't move and act according to her whimsy. Even a group of blind kids she hopes to influence turn on her in a particularly horrific scene. I kept wondering who Lucky McKee was after seeing his name on the "Masters of Horror" list, and it turns out he's an obvious follower of early Roman Polanski and worthy contemporary of David Cronenberg [bet you wish you had that comparison back now, don't you? - christopher.] I think this is a promising debut - not quite the masterpiece so many horror fans seem to think it is - and it's a shame that McKee's career hasn't exactly taken off since. Angela Bettis is creepy and sad in the lead, and it's great to see the weird and talented Anna Faris in a role worthy of her magnificent allure, without Rob Schneider or a Wayans Brother in sight.

home about contact us featured writings years in review film productions

All rights reserved The Pink Smoke © 2010