LAMBERTATHON:

SUBWAY [1985]

john cribbs

Christopher Lambert first appeared on the big screen in a loin cloth, swinging into audiences' hearts as Tarzan, lord of the apes. Since then he has enjoyed a successful 25 year career as actor, producer and occasional thunder god. Although he counts himself among the star's many fans, John has actually only seen a handful of Lambert's more popular movies (the Highlanders, basically) and therefore made tbhtgnu he questionable decision to embark on the ambitious and possibly pointless task of seeing all the French-American's films from Greystoke on. That's over forty films, but John isn't sweating it. It's time for a new kind of magic. Nothing in the world has prepared you for this. John is building a fortress for the ultimate takeover... your mind! This is his own personal

Christopher Lambert first appeared on the big screen in a loin cloth, swinging into audiences' hearts as Tarzan, lord of the apes. Since then he has enjoyed a successful 25 year career as actor, producer and occasional thunder god. Although he counts himself among the star's many fans, John has actually only seen a handful of Lambert's more popular movies (the Highlanders, basically) and therefore made tbhtgnu he questionable decision to embark on the ambitious and possibly pointless task of seeing all the French-American's films from Greystoke on. That's over forty films, but John isn't sweating it. It's time for a new kind of magic. Nothing in the world has prepared you for this. John is building a fortress for the ultimate takeover... your mind! This is his own personal

LAMBERTATHON.

<< click here for Lambertathon Part I: Greystoke, the Legend of Tarzan Lord of the Apes>>

<< click here for Lambertathon Part II: Love Songs>>

Before getting into this, the third of my projected 50-part Lambertathon (which I task Chris Funderburg to complete in the event of my untimely death, at least until my daughter is old enough to take over), I want to clarify the way I'll be structuring future installments. Since I didn't have much to say about his second major role in Love Songs, I chose on a whim to include an additional review of that director's adaptation of Man on Fire, a movie filled with more of the kind of things us Lambert fans look for a movie. I ended up getting more responses to the second half of that article, and additionally enjoyed branching off to write about a second film superficially connected to the main subject. So I think from now on the shorter Lambert reviews will be complimented by a follow-up writing on a film that has something to do with the one I'm writing about. This week: Luc Besson's Subway starring Mr. Lambert, with a supplemental look at the director's follow-up film The Big Blue.

We Lambert enthusiasts have had some good news in the last couple weeks. He's allegedly joined the cast of The Job alongside Jason Statham, Thomas Jane and Franka Potente. That's like a dream cast of mine, not to mention that Statham has had a good run with "job" movies (when can we expect The Hand Job?) I don't know much about this writer-director Brad Mirman, but he did write five previous Lambert movies so I guess that's a good sign. Lambert is also reportedly teaming with Albert Pyun (more on him later - he's almost the co-star of this writing experiment) for a third time on the upcoming Tales of an Ancient Empire. Early word says Seagal will co-star, which would be appropriate since Seagalogy by Vern was the inspiration for this whole Lamberathon in the first place. So don't worry gang, even at 53 it seems the man is just getting started.

Any Lambert news is good news. Google name searches come up with more and more of that LamBERT dweeb from "American Idol" every day - it's our job to keep our boy relevant; to pass him down to the next generation. I mean let's face it, the Highlander movies are not exactly the James Bond series (although they tried like hell to make as many of them) and on a good day they're typically seen as a pit stop for the guy who played Bond on his road to the Oscar...they just don't have the same kind of longevity. So what chance do the lesser-known ones have of being deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" by the United States Library of Congress and selected for preservation in its National Film Registry? (Here's a hint: the answer is not Druids). How far are we from a dystopian society that bans outright sexiness and calls for the desecration of all the actor's films? Anyway, let's not look to that day. Instead of 1984 let's look at 1985*, the year of Subway, Lambert's collaboration with future Arthur and the Invisibles auteur Luc Besson.

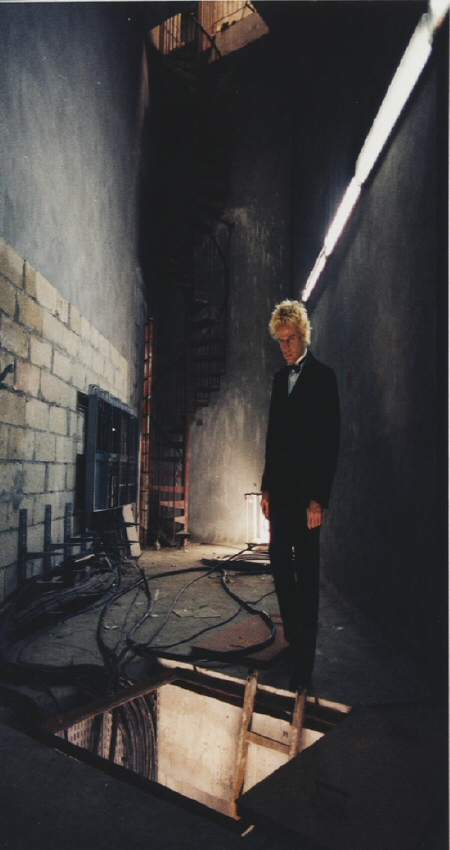

This marks the first time in his career that Lambert gets to open the movie, framed in a generous close-up as he casually races down the Champs Elysees in a tiny two-seat junker. Dressed in formal wear with a shock of white-blonde hair, he would be as colorless as an albino if it weren't for his unmistakably blue eyes. He fumbles around for a cassette tape, spewing profanities, not even reacting when he's rear-ended by a Mercedes full of similarly-tuxedoed men - he's in the middle of a chase! Not only does he not seem to realize the peril, once he gets the cassette in the player he beams, mashes down the stick and lets out one of his trademark laughs as Eric Serra's theme music blares from the speakers. The two cars weave heedlessly through traffic, dive in and out of tunnels. In his careless speed ecstasy, Lambert blasts through an iron fence and nearly decapitates a middle-aged jogger. Suddenly the music stalls, the cassette sputters out of the player and, the momentum lost, Lambert crashes his car through a nearby subway entrance. The goons in the pursuing vehicle get out and try to follow him, but he's already on a train descending into the underground tunnels.

This marks the first time in his career that Lambert gets to open the movie, framed in a generous close-up as he casually races down the Champs Elysees in a tiny two-seat junker. Dressed in formal wear with a shock of white-blonde hair, he would be as colorless as an albino if it weren't for his unmistakably blue eyes. He fumbles around for a cassette tape, spewing profanities, not even reacting when he's rear-ended by a Mercedes full of similarly-tuxedoed men - he's in the middle of a chase! Not only does he not seem to realize the peril, once he gets the cassette in the player he beams, mashes down the stick and lets out one of his trademark laughs as Eric Serra's theme music blares from the speakers. The two cars weave heedlessly through traffic, dive in and out of tunnels. In his careless speed ecstasy, Lambert blasts through an iron fence and nearly decapitates a middle-aged jogger. Suddenly the music stalls, the cassette sputters out of the player and, the momentum lost, Lambert crashes his car through a nearby subway entrance. The goons in the pursuing vehicle get out and try to follow him, but he's already on a train descending into the underground tunnels.

Like Besson's previous film Le dernier combat, this one is deceptively thrilling at the onset, starting off with such a burst of creative energy that you're expecting a feature-length thrillride. But after the opening scene it's almost like the filmmakers go off to try and think of something exciting to follow it up with, leaving the audience to sit there with the movie until they come back. "Just sit here and watch over the movie, guys, we'll be back in a jiffy." Then 30 minutes later you kind of look around and ask the person next to you "Those guys said they were comin' back right?" The remaining 85 minutes of Subway is meditative but largely plotless, like a dream being described to you by someone who's still trying to figure out the symbolism of it himself. It needs to be said: for a movie that takes place almost entirely in the subway, where you think of constant movement a'la trains, and is in fact called Subway there's very little movement. The film and its characters are actually anti-movement: it opens with three philosophical quotes about existence: Socrates, "To be is to do," Sartre, "To do is to be," and Sinatra, "Do be do be do." The message is clear: Besson thinks it's a crazy world up there on the surface what with folks insisting on constantly "doing" things. To him the subway is someplace no square bozo would ever think about not moving swiftly through without a thought, therefore it's the ideal environment for outsiders who seek an eden of in-action; a stasis salvation. Not that the collective ennui doesn't mean anything: Subway is the first in an early trilogy by Besson that's all about freedom. In The Big Blue, it's the freedom of deep sea diving (Besson himself was an avid diver until an accident at 17 made it so he could never do it again) while the title heroine of Nikita seeks freedom from the brainwashed life of government-created assassin. The theme is most prominent in Subway, which is about freedom from social responsibility - "What about food here?" Lambert asks one of the underground denizens, who responds indignantly, "What about life insurance while you're at it?" - and the law.

The whole thing hinges on a cryptic blackmail scheme by Lambert's Fred, who in the opening scene is fleeing from a birthday party for high society model Isabelle Adjani, during which he couldn't help himself and blew the house safe, making off with its undisclosed but clearly sensitive "documents." Adjani turns up in the metro, understandably angry at Lambert but undeniably intruiged by him, still wearing her party dress. It would have been funny if Besson had Adjani stay in the evening dress for the entire film...I thought she was when, the second time we see her, she's still wearing it in bed in the middle of the night (it even seems like Lambert is going to stay in the tux until the end, but mid-film he changes into a trenchcoat like the one he wears at the beginning of Highlander). It would have been even more poignant if she had kept it on perpetually, as her own personal oppression comes in the form of a ruthless gangster who keeps her as an indentured trophy wife. Adjani, who performed her most notorious film scene in a subway, begins to feel the same way Fred does: maybe the perceived useless life of a homeless subway dweller is more liberating than she thought.

"Sometimes you're terrific, and most of the time unbearable" Adjani's Helene informs Fred. It's true: Lambert turns Fred into a memorable character of consistent contradiction. He often runs around like a gleeful child arranging his train set (a life-sized one), charming his would-be metro cop captors and positing himself as a kind of Orphean patriarch to the shiftless outcasts by selling them on the idea of forming a band to perform a concert in the crossroads of the underground tunnels (the film's closest resemblance to a narrative thread). He's playful with a dark streak: in one scene he grabs one of the urchins by the hair and presses a gun - loaded with three bullets - against his cheek and pulls the trigger, luckily on an empty chamber, before handing the weapon back and chuckling mischeviously. On more than one occassion Lambert seems to be getting genuinely angry or frustrated but quickly drops it in favor of a dismissive laugh like it was all a big joke. His big blonde hair is almost like a clown's wig, although the contrasting formal wear and later loose, dirty outfit seem to suggest an escapee from the lunatic asylum. The emotional mood swings he goes through are schizophrenic, particularly a monologue he delivers about losing his voice as a child and being unable to fulfill his dream to be a singer in a band which ends with Helen pulling a gun on him, at which point he asks "Did you buy that story?" Every serious moment is followed by a laugh or grin to imply he's not being serious, most notably his "death" at the end of the film after he's been shot and dies in Helene's arms only to open his eyes, sing along with the band and grin after she's left (the shot itself is ambiguous - we don't hear the bullet or see any blood). The very nature of the character is postmodern overkill, suggesting perhaps Besson's basic unease in portraying flat-out drama.

"Sometimes you're terrific, and most of the time unbearable" Adjani's Helene informs Fred. It's true: Lambert turns Fred into a memorable character of consistent contradiction. He often runs around like a gleeful child arranging his train set (a life-sized one), charming his would-be metro cop captors and positing himself as a kind of Orphean patriarch to the shiftless outcasts by selling them on the idea of forming a band to perform a concert in the crossroads of the underground tunnels (the film's closest resemblance to a narrative thread). He's playful with a dark streak: in one scene he grabs one of the urchins by the hair and presses a gun - loaded with three bullets - against his cheek and pulls the trigger, luckily on an empty chamber, before handing the weapon back and chuckling mischeviously. On more than one occassion Lambert seems to be getting genuinely angry or frustrated but quickly drops it in favor of a dismissive laugh like it was all a big joke. His big blonde hair is almost like a clown's wig, although the contrasting formal wear and later loose, dirty outfit seem to suggest an escapee from the lunatic asylum. The emotional mood swings he goes through are schizophrenic, particularly a monologue he delivers about losing his voice as a child and being unable to fulfill his dream to be a singer in a band which ends with Helen pulling a gun on him, at which point he asks "Did you buy that story?" Every serious moment is followed by a laugh or grin to imply he's not being serious, most notably his "death" at the end of the film after he's been shot and dies in Helene's arms only to open his eyes, sing along with the band and grin after she's left (the shot itself is ambiguous - we don't hear the bullet or see any blood). The very nature of the character is postmodern overkill, suggesting perhaps Besson's basic unease in portraying flat-out drama.

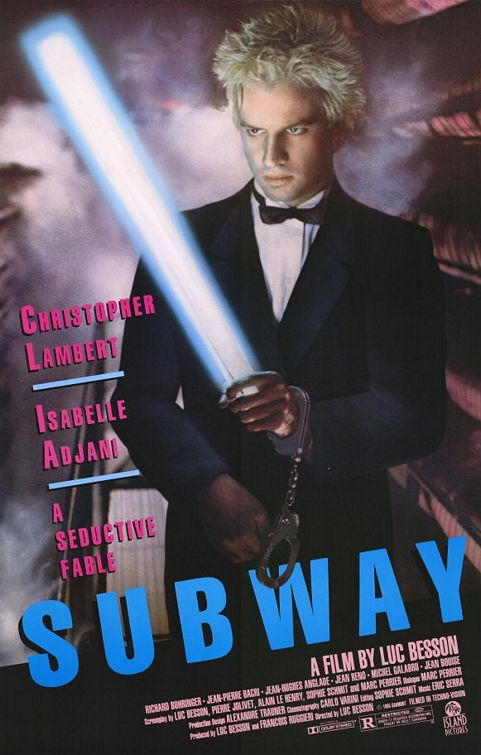

Of course Lambert's look is great: I remember seeing the poster for the first time many years ago and thinking how iconic he looked with his spiky blonde mane. Somehow he makes such a controlled hair-style look roguishly messy. Besson would give Bruce Willis a similar "blonde fro" in The Fifth Element, but Bruce and his hairline just couldn't pull it off the same way. The interesting casting and costuming the eccentric chracters provide the thin narrative some much-needed substance. Somewhere between the happy homeless of Miracle in Milan and Jeunet's circus freaks from the recent Micmacs, the group of eccentrics include a purse-snatching roller skater (the movie's most moving image is the shot of him helplessly stripped of his skates and handcuffed to the desk inside the metro police station), a strongman named Big Bill, composer Eric Serra as a man who lets his 'baddest bass' do the talking, and Jean Reno as the nameless Drummer who goes around in a leather coat rapping his sticks against every surface of the subway (when the band gets together for the final show it's a shame we've already seen this character behind a set: it would have been better if we didn't know whether he was actually a solid banger until this last scene, which is presented as kind of a magical moment for no reason.)

Personality-wise the gang is limited to their outsider features and occasional weird dialogue - Big Bill, Serra and Reno have maybe half a dozen lines between them - but all the characters fit into what French critics at the time declared the new "Cinema du look." Subway was grouped with Beineix's Diva and Betty Blue and Leo Carax's Bad Blood and Lovers on the Bridge, as well as Besson's own The Big Blue and La Femme Nikita, as some sort of a new New Wave tied together mainly by their reliance on style over substance. It's funny: when you group all those movies together, I totally get the similarities. Young, alienated characters without families flaunting specific post-punk chic fashions and short-haired heroines suffering existential relationship crises, not to mention the reliance on primary colors and widescreen photography and visual allusions to advertising, pop art, youth subculture and magazine cut-outs...it makes sense. I would go so far as to suggest that Roger Avary's Killing Zoe was clearly influenced by these kind of movies and, if we're gonna call it a movement, should be added to the list (and not just because Jean Hugues-Anglade is in it). On the other hand, these movies weren't inspired by some kind of political or social turn in France, and I'm not sure any of them have any interest in representing the marginalized youth of the Génération Mitterrand. Besson himself was uncomfortable with the association; whether his migration to America and broader big budget genre pictures was a reaction to it is up for speculation.

It would make sense that Subway would ignite its own movement, considering its obvious debt to Breathless. The boy-meets-girl, girl-betrays-boy, girl-watches-boy-die doomed love affair story isn't unique to Godard's film, but the playfulness, the intelligent, tough-yet-goofy charm of the characters and fragmented narrative make comparisons inevitable. Subway shares that classic film's mingling of popular and high culture, turning tuxedos and dinner dresses into stylish "rebel" clothes and replacing an orchestra planning to perform Bach for a crowd with the synth-rock band "modern" band put together by Fred. Godard's attestment that "all you need for a movie is a girl and a gun" seems fulfilled by Adjani's unlikely femme fatale, who impatiently barks "Haven't you seen the movies? Stick 'em up!" when Fred regards her drawn firearm with mere curiosity; later, she furthers the post-modern connection with the very Godardian line: "There are some men who want to kill him...like in a cowboy picture." Of course there was Harlan Ellison's comparison of Lambert's sleepy visage to that of Belmondo, and Fred is just as singularly charming as the fugitive Michel. His last words to Helen (not mistranslated by a policeman) are "Tell me something...do you love me a little bit?" She kisses him, and he says "I'm gonna call you later" before dropping his head, a nod to Belmondo's final Le doulos farewell as well as an amusing hint that maybe Fred's still just playing around after all (although he doesn't break the fourth wall a'la many a Godard actor, Lambert's grin is as good as a wink to the audience). To me the clearest indication that the movie was a conscious unofficial remake was Helene's reply when Fred asks if he'll see her again: "Don't hold your breath." Its homages to Breathless consequently make it as referential to films of the past as Godard himself, but that's getting into some kind of mind-blowing meta territory that goes beyond a series about the movies of Christopher Lambert...

It would make sense that Subway would ignite its own movement, considering its obvious debt to Breathless. The boy-meets-girl, girl-betrays-boy, girl-watches-boy-die doomed love affair story isn't unique to Godard's film, but the playfulness, the intelligent, tough-yet-goofy charm of the characters and fragmented narrative make comparisons inevitable. Subway shares that classic film's mingling of popular and high culture, turning tuxedos and dinner dresses into stylish "rebel" clothes and replacing an orchestra planning to perform Bach for a crowd with the synth-rock band "modern" band put together by Fred. Godard's attestment that "all you need for a movie is a girl and a gun" seems fulfilled by Adjani's unlikely femme fatale, who impatiently barks "Haven't you seen the movies? Stick 'em up!" when Fred regards her drawn firearm with mere curiosity; later, she furthers the post-modern connection with the very Godardian line: "There are some men who want to kill him...like in a cowboy picture." Of course there was Harlan Ellison's comparison of Lambert's sleepy visage to that of Belmondo, and Fred is just as singularly charming as the fugitive Michel. His last words to Helen (not mistranslated by a policeman) are "Tell me something...do you love me a little bit?" She kisses him, and he says "I'm gonna call you later" before dropping his head, a nod to Belmondo's final Le doulos farewell as well as an amusing hint that maybe Fred's still just playing around after all (although he doesn't break the fourth wall a'la many a Godard actor, Lambert's grin is as good as a wink to the audience). To me the clearest indication that the movie was a conscious unofficial remake was Helene's reply when Fred asks if he'll see her again: "Don't hold your breath." Its homages to Breathless consequently make it as referential to films of the past as Godard himself, but that's getting into some kind of mind-blowing meta territory that goes beyond a series about the movies of Christopher Lambert...

Perhaps in homage to Breathless, very little happens in Subway, making it a tough film to classify. For me the concept of the movie was vaguely reminiscent of Orpheus in the Underworld, Fred's liberating of Helene a substitute for Orphee rescuing Eurydice from hell (or the other way around). I don't know if I give the movie or its maker that much credit personally, although some would: Armond White for one loves Besson, claiming the director "proves that the simplest movies can carry the deepest needs." Unconfirmed inspirations of classic myths aside, I've heard the movie referred to as "black comedy," "psychedelic," "punk-surrealist chic," but honestly none of these really apply to the film at all. They should: the possibilities set up by that energetic opening are limitless. There's nothing "black" about the comedy, because the subject matter (cops and crooks chasing evaders around the subway feel like Mack Sennett-style mayhem) isn't edgy by any definition of the term. Something about the movie feel like fantasy, although nothing fantastical (ruling out Fred's apparent "resurrection") actually occurs. On the poster it looks like Lambert is holding some sort of lightsaber - it turns out to be a fluroscent light that he picks up in one scene for a few seconds to see in the dark (I'm guessing it was sold that way on purpose). Besson has stated in interviews that he wanted to recreate the Metro as a "space station," and some of the backlot sets are designed to look "science-fictiony." In terms of location he's most successful at making the interior, underground setting as disorienting as possible: at one point Fred calls Helene and she reveals that it's 2am, unbeknowst to him in his perpetual dimly-lit world, an "an asceptic somewhat atemporal world" according to Bresson. It makes me wonder how constrained by the budget the director was...we all saw how, in the wake of Leon's success, he spared no expense to splurge on the visually masturbatory world of The Fifth Element. Would Lambert of had an actual light sword if Besson had secured an extra million bucks?

By all rights, Subway should be Lambert's best and classiest film, one that appeals to arthouse nuts, science fiction nerds and action fans. As it stands, it's so frustratingly close to being there - like, one stop away - but doesn't end up satisfying as any of these. Although Fred is possibly the best role Lambert was ever given** and he has an iconic look, the character himself is not nearly fleshed out enough to be a classic one (the same thing could be said for the movie in general). While not anywhere near an entirely successful film, I have to admit I liked it a lot better now than I did back when I originally saw it. Like Love Songs, the dated, wince-worthy music is an unavoidable issue, but at least Lambert doesn't have to dress like a goofball with rolled-up sports jackets and sing this time. The movie was a hit in France, and Lambert walked away with a Cesar Award for Best Actor (the movie also won trophies for production design and sound). Besson offered him the lead in The Big Blue, but Lambert was already committed to The Sicilian...

(CONTINUED ON NEXT PAGE)

* I realize that's the second Orwell-related joke I've made in the pages of Lambertathon. I'll try to squeeze Aldous Huxley into the next literary quip.

** I know it may seem premature to declare the third movie I've watched for this series as his best performance - I'm just assuming he's better utilized here than in Mortal Kombat.

<<Previous Page 1 2 Next Page>>

home about contact us featured writings years in review film productions

All rights reserved The Pink Smoke © 2010