lambertathon:

MORTAL KOMBAT

martin kessler

As we all know when it comes to Christopher Lambert, there can be only one. However, writing about every movie in an actor's 30+ year filmography is a big job - too much for one man who's got Holophonor lessons and day-long trips to any convention where Taimak will be signing. So for this installment of the epic Lambertathon, we turn to Martin Kessler, writing his first piece for The Pink Smoke.

Mr. Kessler is a known Canadian and an alleged movie maniac (charges pending) so he's naturally the perfect person to host the Flixwise podcast spin-off, Flixwise: CANADA. Check it out: it focuses in equal measure on Andrei Tarkovsky and Paul W.S. Anderson. Which brings us to this: it's time for a new kind of magic. Nothing in the world has prepared you for this. Martin Kessler is building a fortress for the ultimate takeover... of your mind!

This is his shared but still personal...

LAMBERTATHON.

MORTAL KOMBAT

paul w.s. anderson, 1995.

The first Christopher Lambert film I saw was Mortal Kombat. It also happened to be my first Paul W.S. Anderson film (back when he was just Paul Anderson, before the other Paul Anderson came onto the scene). I went to see it with my mother in 1995, when I was six years old. Then new to Canada, I could understand little English and had never played any of the Mortal Kombat video games, but the clear visual storytelling made it easy to follow. It was a film that spoke in images.

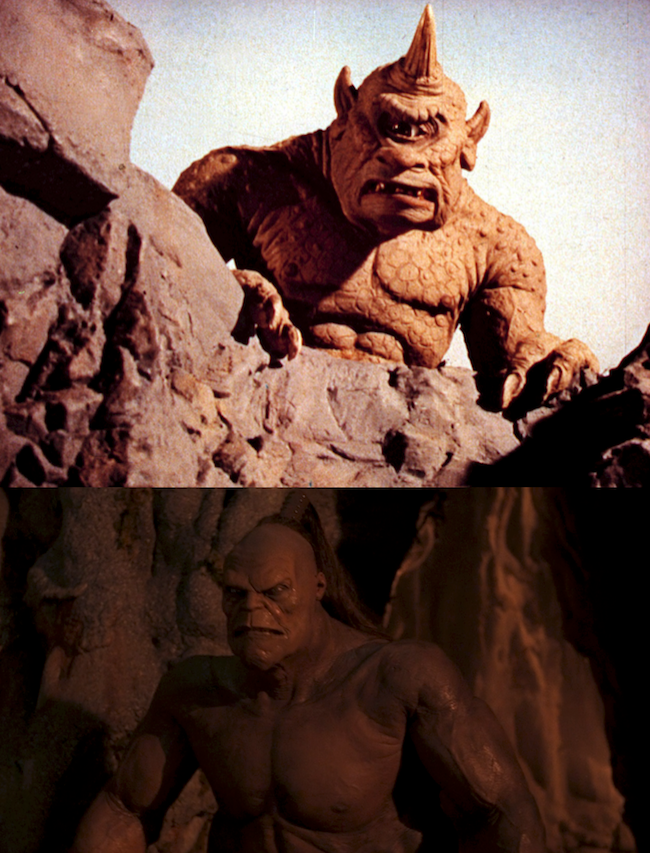

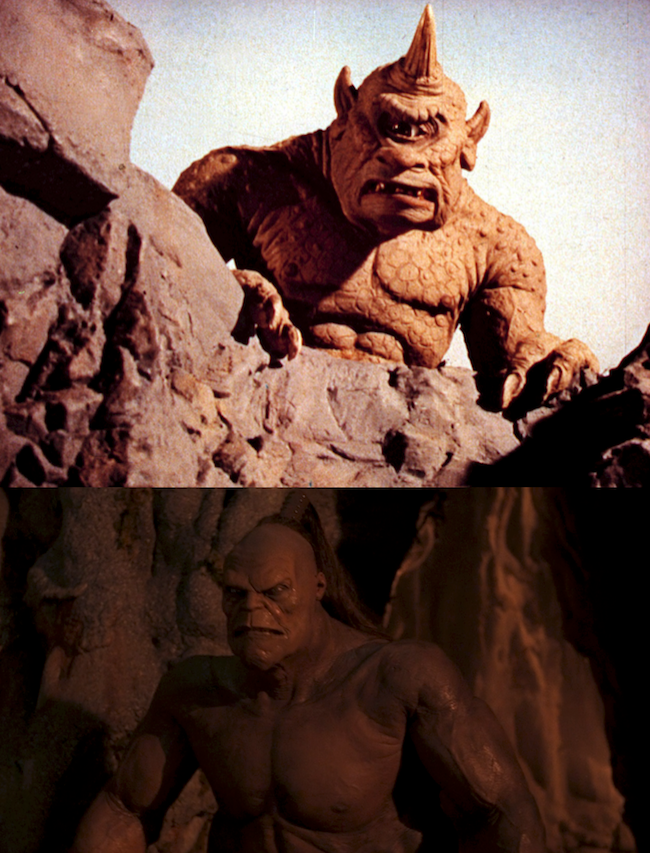

I enjoyed the thing most kids enjoyed in the film at that time: the adrenaline-inducing action and that thrilling techno theme song. It became a regular rental when it finally arrived at the local video store, and that Halloween I went as the monster Goro in a costume made by my mother. Don't worry, this isn't a nostalgia piece. Liking a film as a child isn't a reason for me (or especially you) to like it now.

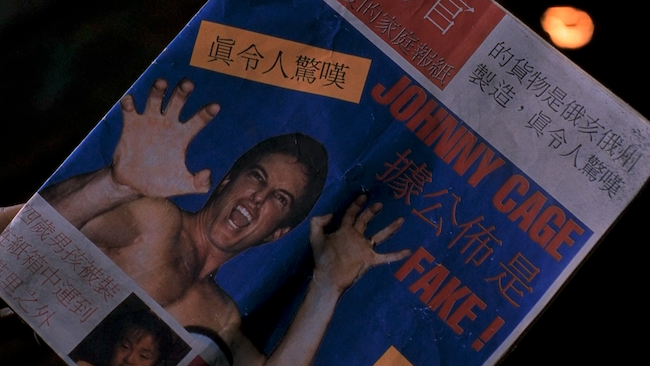

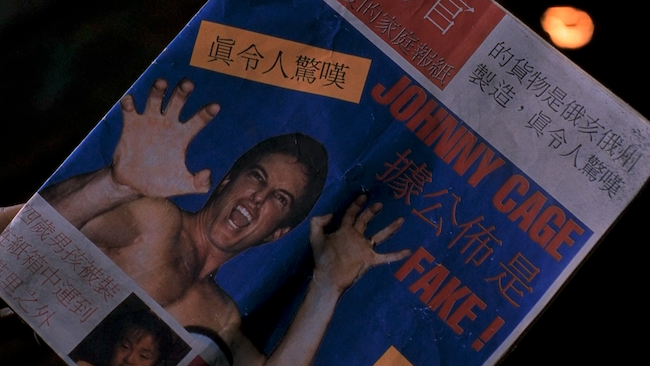

But thinking back, the thing in Mortal Kombat that may have left the strongest impression on me was a small, understated moment early in the film. The martial arts movie star character, Johnny Cage, is introduced filming an action flick directed by a Spielberg parody. There's a shot of a scenic skyline, just like many others that appear later in the film. Johnny Cage walks past it, and the camera pans to reveal that it's just a backdrop. It's not real. It's a movie. A winking peeling back of the artifice of the film, and a declaration that nothing else to come would be real either.

Two decades later I would hear Paul Anderson describe a similar experience when talking about his inspiration for becoming a filmmaker:

"I remember having this epiphany when I was probably about six years old, seven years old... It was a John Wayne film and it kind of suddenly clicked that John Wayne wasn't really a cowboy, he was someone pretending to be a cowboy. And that this wasn't reality, this was make-believe. This was a story that people had made and somehow got on this big screen. And as soon as I realized that movies were made-artifacts, I thought 'that's what I want to do with my life. That's the only thing I want to do with it.'"

I can't give Mortal Kombat full credit for making me want to be a filmmaker, but I'm sure it helped in its own way. My personal desire to become a filmmaker feels like the result of an accumulation of those sorts of moments. The moments when 'movies' suddenly means something different to you than it did seconds earlier. I still live for those moments.

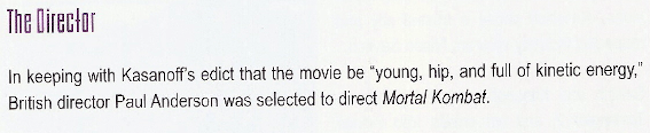

I remember renting a computer-animated Mortal Kombat video before the feature film's home video release. After the cartoon there was a short featurette, the sort of featurette that exists to sell you on the film more than give any real insight. I watched it over and over again. Producer Lawrence Kasanoff (who had worked with James Cameron and Kathryn Bigelow in the '90s and would produce the Mortal Kombat sequel, the sci-fi Beowulf movie starring a white-haired Lambert and announce that Tetris movie which as of this time has yet to materialize) pitches how great the film is going to be to you. He manages to sound like a used car salesman espousing the features of a product he wouldn't buy himself. He offhandedly belittles Hong Kong martial arts films, too. Stunt co-ordinator Pat Johnson (who's worked with everyone from Bruce Lee to Lexi Alexander) seems to speak directly to parents, reassuring them of the virtues of martial arts. He promises that the characters in the film would be positive role models for their children, a dissuasion of the controversial violence of the video games the film was based on. In the featurette they're both presented with more importance than the enthusiastic but shy and self-effacing young director. If you didn't know what a film director was, and watched that featurette, you could easily assume they weren't all that essential to a movie being made.

Paul W.S. Anderson was perhaps better suited to direct a video game movie than anyone else in film. That might sound like a damning statement. Do you ever hear a film is "like a video game" and get excited? But if there's any artistic legitimacy to be found in the 'video game movie', it would be in Anderson's films. His films embraces the qualities that make video games what they are instead of treating them like obstacles. All of his films, not just the ones based on video game properties.

Anderson's predilection and skill for blending video game conventions with the cinematic goes back to his first feature film, Shopping. In one of the film's most memorable scenes, Sadie Frost plays a hand-held Grand Theft Auto-style video game during a car chase with police. It foreshadows the video-gamey-come-cinematic direction his career would take. Maybe even a private prophecy that would be fulfilled with his second feature film, Mortal Kombat. Don't worry, this isn't a vulgar auteurist piece either.

Anderson described himself as a fan of the Mortal Kombat games. It's the sort of thing every filmmaker charged with working with some pre-existing property says to cultivate fan approval: I'm one of you! But when Anderson goes on to describe his trips to London during pre-production of Shopping, going to the arcade to spend his free time because he didn't have any friends or know anyone around, he sounds sincere. I actually don't care if Anderson's genuinely a fan or not. I don't really care about the Mortal Kombat video games, or really even games in general, but what he sees in them - that I care about. Behind game worlds navigated by game characters, fast and violent, there’s a quiet pursuit of some elusive truth where the artificial overwhelms the authentic.

I rewatched eXistenZ (starring Jude Law, who began his career in Shopping) not too long ago. Cronenberg can intellectualize video game realities, but Anderson can make you feel them.

Looking back at Mortal Kombat today, it can be so beautifully unreal. Occasionally I'm reminded of Fritz Lang (Anderson's favourite filmmaker) while watching.

The sets look like sets, but in a way that can make you want to wander around in them. To touch them. Get lost in them. Sometimes I wonder if they end right at the edge of the frame, existing entirely within it, or if they go just a tiny bit beyond.

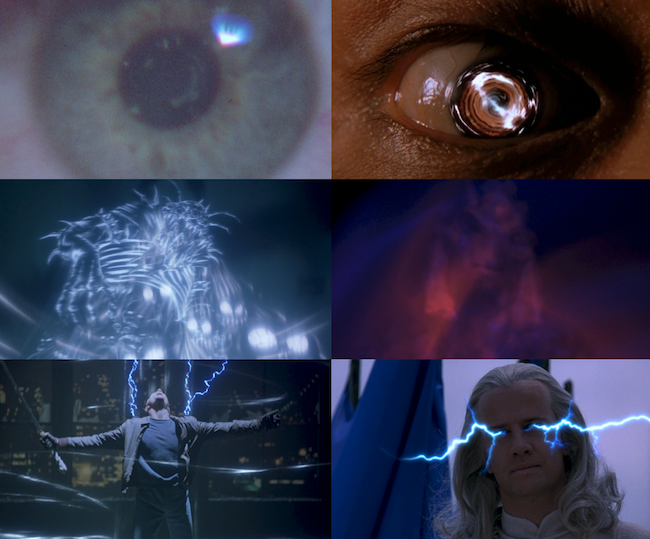

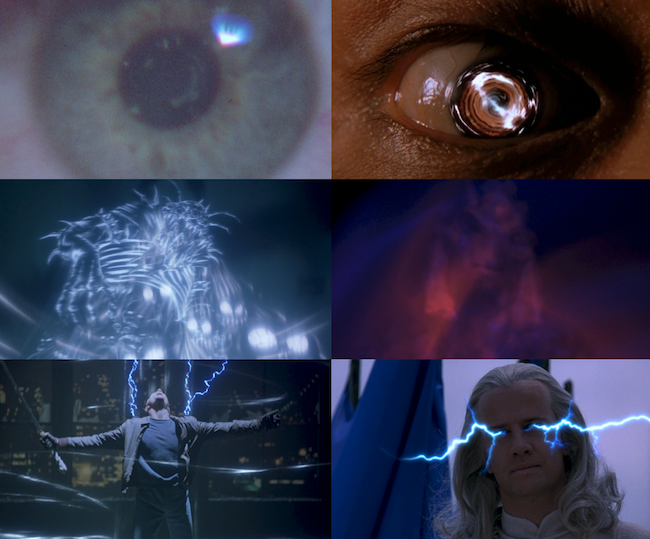

The computer generated effects never look real. Instead they look like magic. The sort of splendorous fakeness of a Georges Méliès film.

The practical effects make you feel like you've crash-landed on Planet Harryhausen. The Goro monster at moments could be mistaken for stop-motion animation, even though it's an animatronic worn by special effects artist Tom Woodruff, Jr. (who was inside the alien costume in Aliens, Alien 3, Alien: Resurrection and Paul W.S. Anderson's own Alien vs. Predator). Anderson would compare the story of Mortal Kombat to a film featuring some of Harryhausen's most renowned work: "Jason and the Argonauts is an old-fashioned mythic movie with a simple premise of good guys on a quest and bad guys out to thwart that quest. That's what attracted me to Mortal Kombat. It's a story that centres on a classic mythology."

It might be worth pointing out that Mortal Kombat begins in a dream. A nightmare fight sequence depicting the death of the hero's brother. The brief scene is punctuated with the face of the villainous sorcerer, Shang Tsung, morphing into a ghoulish skull, like Kriemhild's dark prophecy of the murder of her lover in Lang's mythic Die Nibelungen: Siegfried.

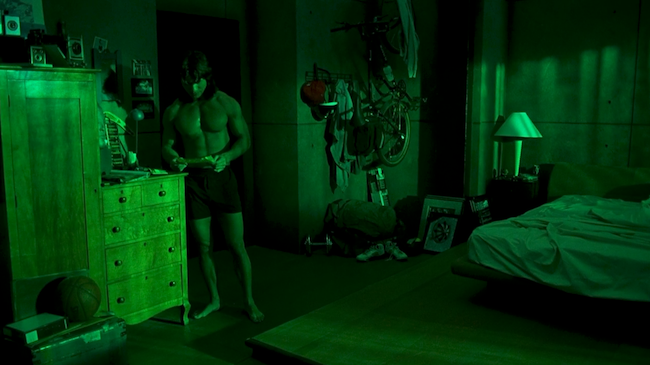

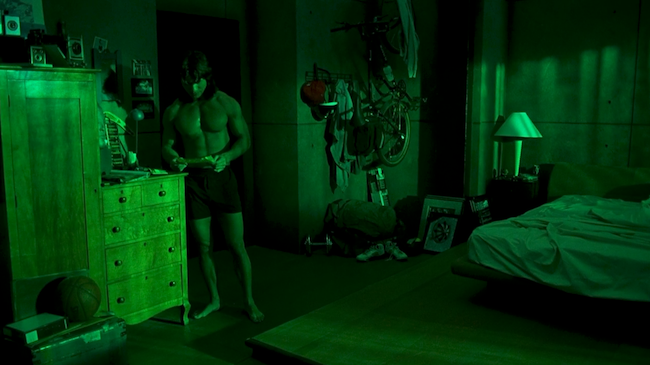

It’s an appropriately surreal moment for a nightmare, but then the scene ends and we're in the apartment of the film's hero, Liu Kang (played by Robin Shou, who would work again with Anderson in Death Race and train Milla Jovovich for Resident Evil). It's bathed in an unnatural green light. The reality of the film to which we're introduced is no less dream-like. There's the sound of thunder (the exact same thunder sound effect used heavily in Event Horizon) and a repeat viewer might be invited to consider whether Liu Kang's nightmare was a vision sent by the thunder god character, Rayden. Even if you don't want to bother speculating on the mystical or cine-metaphysical mechanics of the world of the film, it's still a nice bit of foreshadowing. (We'll get to Lambert, I promise.)

Like the Outworld dimension where the characters in the film travel, watching Mortal Kombat I frequently feel transported into another reality with its own strange rules rooted in cinema rather than life. Admittedly that's not always the case. The film occasionally dips into the downright pedestrian. I don't want to point out everything overly-broad or clumsy or what's become unfashionable (the hair!) They're self-evident to anyone who decides to watch the film today and reflect the work of a director finding his footing in a particularly commercial, producer-driven arena. Anderson fairs better than most though. The flourishes are enough to carry me through it all. And as you'd expect, the forgettable bits are quickly forgotten.

For my money, the best sequence in Mortal Kombat is the nearly wordless five-minute fight between Johnny Cage (a character preoccupied with fakeness) and the dead-eyed yellow-clad supernatural ninja, Scorpion (his yellow that somehow screams '90s to me, the same yellow of the warrior bugs in Starship Troopers). It may be the longest uninterrupted stretch of the film where purpose and imagination inform every shot (the following fight scene with the blue ice-powered Ninja is underwhelming in comparison). It begins in a forest. A Thai rubber plantation. Trees planted in neat endless rows, giving the exterior location a stunning and uncanny artificiality. A grid (a pet motif of Anderson's). It's not a location established earlier in the film. And there's no explanation given as to what the characters are doing there. It just is and they just are. Like a dream. Fight!

I like the way depth is played with. Usually Anderson prefers wide angle lenses, but here long lenses flatten the image out, emulating the look of the two-dimensional Mortal Kombat games. A CGI monster emerges from Scorpion's hand and springs out toward the camera.

I think 3D films are somewhere between gimmick and scam, but it makes sense that years after Mortal Kombat Paul W.S. Anderson would be one of the first to effectively capitalize on the post-Avatar 3D push. His films were always shot as if they were in 3D.

With a wavy special effect the venue suddenly changes. Like a dream. The fighters are in a hellish domain covered in web-coated bamboo scaffolding and ladders and bones. It's here where it becomes easy to reconcile Anderson speaking as fondly about Italian Futurism as he does about Hong Kong action movies. Squint and you can see Thaïs in it. Squint again and you can see Once Upon a Time in China II.

There's a beat where Johnny Cage loses sight of Scorpion. The camera pans away as he looks around, then pans back to reveal Scorpion standing right behind him. It's uncanny.

I wouldn't dare put Paul W.S. Anderson on the same level as Andrei Tarkovsky. He's not. But that sort of spatial anomaly sets off some of the same neurons in my brain.* Like that shot in Nostalghia of the woman and children who appear twice in the same unbroken shot (achieved by the actors running behind the camera to their new marks as soon as they were out of frame). I don't think Anderson was trying to evoke Tarkovsky, at least not in this film (Resident Evil: Retribution is practically a love letter to Soviet filmmakers). My cine-apophenia isn't that bad. Here it seems more rooted in the spatial impossibilities of video games. Fly off the right side of the frame in Asteroids and you'll come out on the left.**

The action is best when it's shot in wides. Paul Wide Shot Anderson. The environment dominates the frame. Camera movement is slow and deliberate. The physical performances of the actors are unobstructed by over-editing and are easy to follow. The way Sally Potter films the dance sequences in The Tango Lesson. The actual fight choreography (Liu Kang actor Robin Shou choreographed the scene) is pretty routine when you compare it to a contemporaneous film like Fist of Legend. But it's refreshingly stripped down and clear compared to the martial arts scenes Hollywood can get away with right now.

The sequence climaxes with Scorpion pulling off his mask to reveal a skull that spews out fire, in one of the moments in the film that most exactly realizes an image from the games. On my most recent watch I said it was "striking." My girlfriend said it was "metal."

I've seen the same people praise a comic book movie being faithful to the comic on which it's based, but damn a video game movie for being faithful to the video game it's adapting. Just an observation. I'm not bitter or anything, I'd like this sequence even if it had nothing to do with the games.

It's a beautiful five minutes, if you look at it the right way. It exists as an island in the middle of the film. A closed circuit scene. It does next to nothing to serve the film's plot. Mortal Kombat didn't have a proper script during its pre-production, just a 20-page outline (a rare instance of Anderson directing without having a hand in writing). I wonder if this sequence is a byproduct of that? A set piece conceived with only a loose idea of how it might fit into the rest of the film? I don't think that's a bad thing at all, but I've also never been very plot-fixated as a film viewer.*** The literal-mindedness of conflating plot with story never sits well with me. It's like trying to count Louise Brooks' teeth instead of enjoying her smile.

It's strange too sometimes, seeing cinematic homage filtered through the game and back into film form. A pop entertainment hall of mirrors.

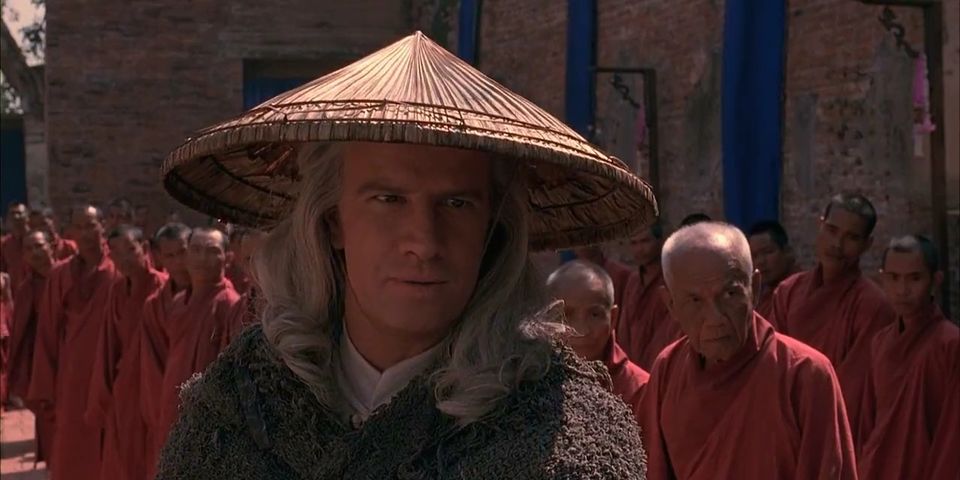

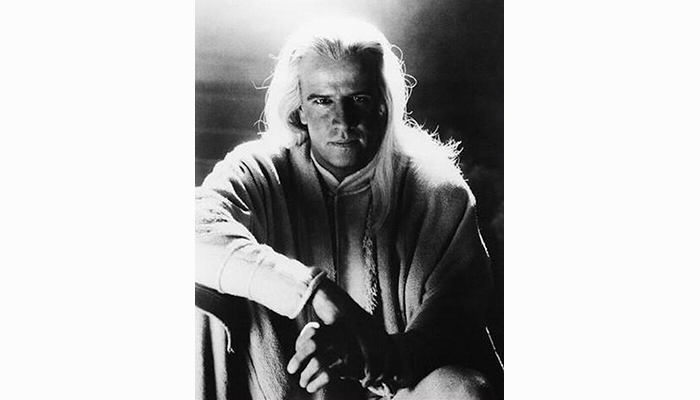

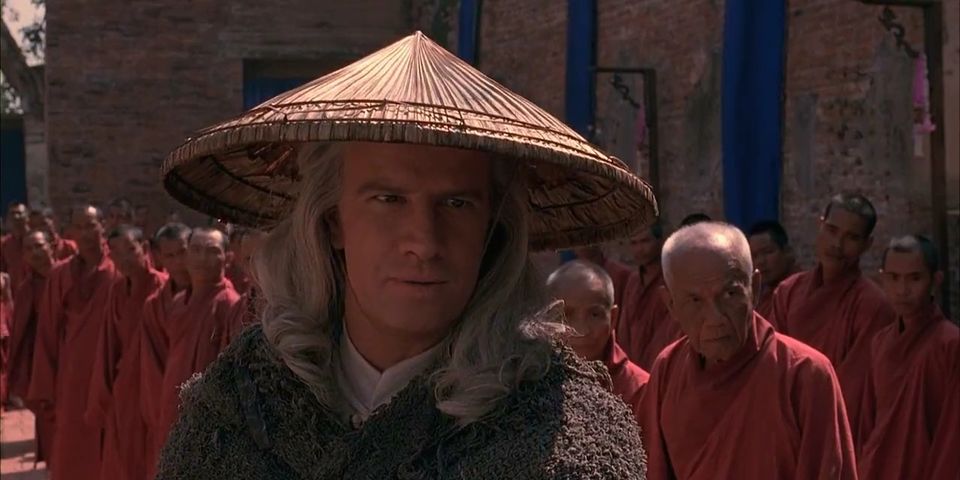

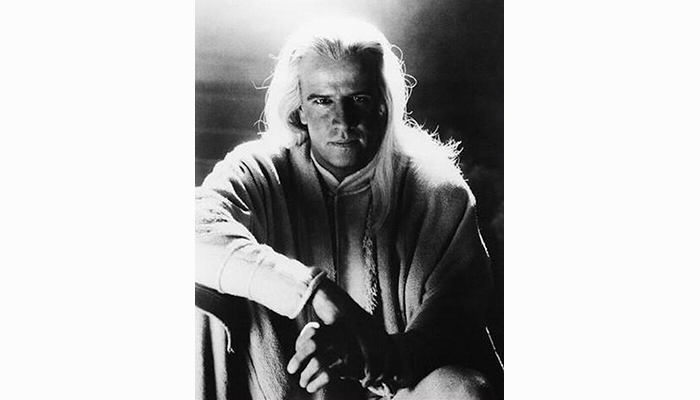

While never pastiche, Anderson's films are peppered with homage and allusion, to video games and to other movies as well. The one that stands out the most in Mortal Kombat is the casting of Christopher Lambert as the likeable, laid-back God of Thunder, Rayden. His charming otherworldliness sets the tone of the film. Who else better to play the anti-titular immortal than the eternal Highlander himself? By the time I eventually saw Highlander and made the connection, it felt like getting the punchline to a joke a couple years late. (Highlander director Russell Mulcahy would eventually direct the Paul W.S. Anderson penned and produced, Resident Evil: Extinction, the third film of that franchise.)

I'd guess Christopher Lambert (who would return to video game realities with Nirvana) was and still is the most identifiable actor in the film. He doesn't really need to do much acting, even physical acting (Lambert was thankful for Mortal Kombat being 'the one and only action movie' he didn't have to train for). Mostly it's just his unique presence and cultural cache which Mortal Kombat benefits.

Lambert is the movie's defacto 'Alec Guinness as Obi-Wan Kenobi'. Or maybe 'Sean Connery as Ramirez' if you prefer.

I was a bit surprised when I read how Lambert saw the character: "Rayden possesses enormous power, but he's lonely at the top. Sometimes he wants to have fun and connect with humans, like a mortal." It's an interesting insight. Like the portrayal of Willem Dafoe's vampire in Shadow of the Vampire, seeing the character of Dracula as lonely.

I'm looking at a little black and white production photo of Christopher Lambert right now. It's too bad Béla Tarr's retired. I wouldn't have minded seeing Lambert have a role like Tilda Swinton's in Man From London. All he'd need to do is be there and bring his face, and it'd be great. Just a thought.

It sounds like Lambert did as much to set the tone of the film behind the scenes as he did on screen. Anderson said of him, "When you make your first Hollywood movie, there's a great danger as a young filmmaker that you will be overwhelmed by the scale of them. Having the big guy on set, the person who is being paid the most money, who is the biggest name, be someone like Christopher really helps you. He was laid back, and he was chill, and nothing was too much trouble for him. And that person sets the tone on the set. Because if it's not any trouble for him, it can't be trouble for anybody else."

Because Lambert signed onto the film as its most expensive actor, Anderson originally intended to keep the actor's filming schedule to a minimum. Close-ups of Lambert were to be shot in Los Angeles, then edited together with footage of a double in Thailand. When Lambert found out about that plan, he made the decision to travel to Thailand and shoot all of his character's scenes at no extra cost. He paid for the film's wrap party, too.

Much later I saw Luc Besson's Subway. Christopher Lambert, hair bleached, surrounded by smoke and white artificial light. That punchline-feeling returned.

It'd be obvious that the "Cinéma du look" was a major stylistic touchstone for Paul W.S. Anderson, even if he hadn't said as much: "The film directors who I related to, who were like ten years older than me but were successful... They tended to be French. It was Besson, Beineix, Leos Carax. I loved those films."

There's an understandable desire for filmmakers to ingratiate themselves with the films they love. I wonder if that was Anderson's motivation, at least in part, in casting Lambert. To work with someone who worked with his heroes and maybe pick his brain about them. There are no "honorary Cinéma du look membership" cards, but Mortal Kombat sometimes looks like a filmmaker working hard to earn one. I think eventually Anderson would surpass them anyway. Not so long ago, Carax said that he wished he could make films like Anderson, so at least there's that. Would you hate me forever if I said Resident Evil: Retribution is like Holy Motors, only better? It is.

Also, I can never resist pointing out that in addition to drawing inspiration from Besson, Anderson would find a muse in - and eventually go on to marry - Besson's one-time collaborator and wife, Milla Jovovich. Anderson once said of her: "She makes you believe all of the movie-making artifice, and she makes you invest in it."

Milla Jovovich, who at one time was the highest paid model in the world. Anderson's films are typically populated with especially attractive people. Handsome men. Beautiful women. I'd develop insta-crushes on Sadie Frost and Sanaa Lathan and Ali Larter. And in their reviews, British critics would try to use Jude Law's handsomeness as evidence for a lack of realism in Shopping.

I'm reminded of a moment in Fred Schepisi's Plenty; a British filmmaker complaining about his actress: "I wish she were more ordinary.... I'm just worried, will the audience identify?" It's played for laughs.

The beauty of Anderson's actors is as important as the aesthetic beauty of his frames. He's unabashed about it, and sees it as another thing that separated him from other British filmmakers: "American movies and French movies tended to have very attractive people in them, and British movies did not."

The cast of Mortal Kombat is not a bad-looking bunch at all. Surprisingly chaste though. Not much sexual tension to speak of. Anderson would compare Robin Shou to Errol Flynn, but his character Liu Kang and the beautiful Princess Kitana (played by model-turned-actress Talisa Soto) never get past flirtatious combat sparing. Asshole-turned-lovable-asshole Johnny Cage and the tough Sonya Blade have an initial friction that quickly blossoms into friendship rather than romance. By the end of the film they're all arm-in-arm. Buddies.

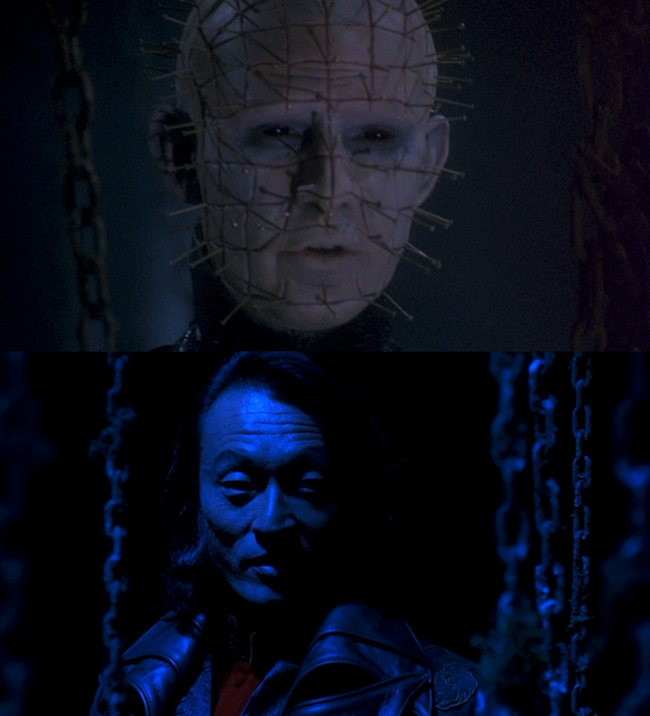

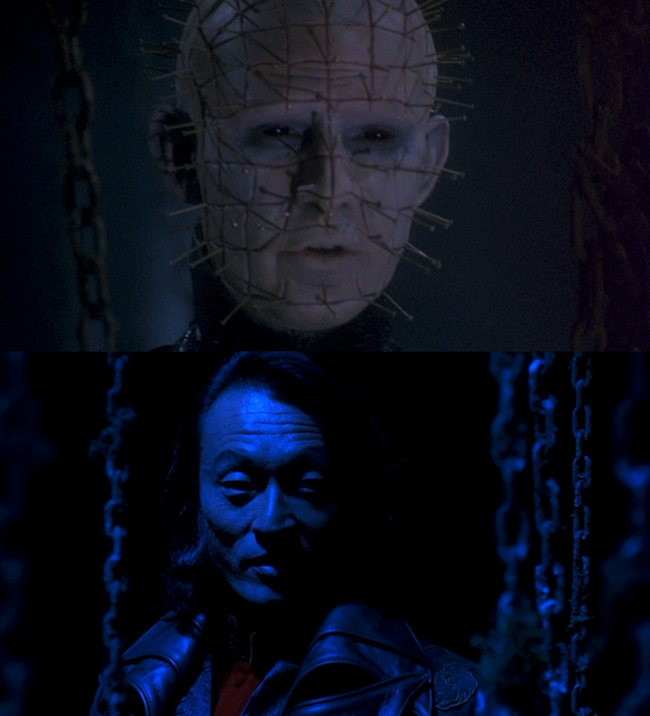

Cary-Hiroyuki Tagawa as the villainous sorcerer, Shang Tsung, does gets to throw out some sexual innuendo. It's still on the tame side, but you get the impression that he's channeling the Marquis De Sade on some level. He's the dark counterweight to Lambert's presence in the film.

In Shang Tsung's ship, he's surrounded by dangling chains, bathed in blue-gelled light. It's an image reminiscent of the cenobites in Clive Barker's Hellraiser (which would be one of the major influences on Event Horizon). I wonder if there's intentionality behind that? Anderson wanting us to see Shang Tsung a little bit like Hellraiser's Pinhead, a leather-clad sadomasochist from an otherworldly realm. I'd like to think so, but your guess is probably better than mine.

Of the major characters, Sonya (played by Bridgette Wilson, a hasty casting replacement after Cameron Diaz broke her wrist training for the film) gets short shrift. Really only one major fight scene and her story proper is over by the mid-point of the film, avenging her dead partner by killing Kano (played with wonderful sleaze by Trevor Goddard). Sonya seems essential enough at any given moment that most people seem to not remember it that way.

Wilson does her own stunts. You can tell she's less experienced with martial arts compared to the other performers. The punches she throws look like she could easily break her wrist, too. She does her best to make up for it with attitude and enthusiasm.

For the rest of the film, Sonya's relegated to an embarrassing bit of damsal-in-distressary, a cliche you don't see in Anderson's other films. Her character arc is 'learning to admit that sometimes even she needs help.' Eesh! It's too bad Anderson wasn't able to write the film. As outrageously pulpy as his scenarios can be, you get a sense that he genuinely respects his characters (especially his female characters). He wants you to care about them.

In a 1995 magazine interview, Anderson would say, "I think people are going to care about Mortal Kombat."*** That statement stands out to me because he doesn't just brace audiences for fluff. In the laserdisc audio commentary Lawrence Kasanoff says, "It's supposed to be fun" and repeats variations of that statement throughout. The more Kasanoff talks, the less I like him. He brags about the film without thinking much of it. You can tell he doesn't really respect Anderson either. Press materials would often present Anderson with all the credibility of a kid who won a contest.

I wonder about the absence of Anderson's producing partner, Jeremy Bolt (who began his film career as an assistant on Ken Russell's Lair of The White Worm and Whore). Bolt produced Shopping and every one of Anderson's films other than Mortal Kombat. In some of the audio commentaries recorded for their collaborative films, you can tell Bolt thinks of Anderson as a friend and equal as well as creative partner. I wonder if the sleazy film producer character in Resident Evil: Afterlife is a parody Lawrence Kasanoff? It's possible.

Obviously Mortal Kombat has its flaws. I'm not sure though when exactly I became aware of the consensus being that it was an outright bad film. Or a so-bad-it's-good, high-camp schlocksterpiece to some (I do laugh when Johnny Cage says he has a "plan" to defeat Goro, which is revealed to be just a punch to the dick). I can understand someone watching the film with ironic distance, enjoying it without the embarrassing uncoolness of enjoying it sincerely, even if I think it means they're missing out on the best aspects of the film. I do think it's often unfairly conflated with its atrocious sequel though. The Honest Trailers parody video dishonestly uses more footage of the sequel than of Mortal Kombat. I think the sequel is a bad film. There's no Paul W.S. Anderson. No Christopher Lambert either.

I don't want this piece to be mistaken as a case for Mortal Kombat as some unrecognized masterpiece. It's not. But I hope anyone who's made it this far will be open to finding the unlikely art in the video game movie. Find personality and beauty and vision in it, past its flaws. That it might provoke contemplation and feeling. That behind its artifice, or maybe even within in it, it might have a soul. It's a film that laughs like Christopher Lambert.

~ JUNE 13, 2017 ~

* There’s a book on my shelf right now called ‘The Cinema of Tarkovsky: Labryinths of Space and Time’ by Norman Skakov. “Labyrinths of space and time” could easily describe Paul W.S. Anderson’s work as well.

** Then again, there’s that Stalker video game, S.T.A.L.K.E.R. I haven't played it though.

*** My favourite film from 2015, Jauja was shot with only a twenty page outline.

**** In that same 1995 magazine interview, Anderson would say: "I learned that I like directing big special effects movies. I don't suspect that my next film is going to be an intimate love story. I'll probably wait until I'm 50 to do that." When Anderson was 50, he would direct the go-for-broke, earnestly romantic Pomeii.