SECOND

CHANCES

c.a. funderburg

In coordination with the release of his newest film, Peterloo, this month The Pink Smoke will be exploring the work of noted curmudgeon and dyspeptic genius Mike Leigh. From his early teleplays to his recent historical dramas, Leigh's focus has stayed constant: the elusive qualities of happiness, the constrictions of family, the friction between the have's and have-not's, the relationship between work and personal fulfillment.

This series, Second Chances, explores our attempts to grasp greatness where we’ve previously failed to find it; to actively make an effort to appreciate esteemed artworks for which we currently have an antipathy. We’ve given cult favorites like Escape From New York another shot and dug deep into the filmographies of beloved auteurs whose appeal eludes us (like Nicholas Ray.) The goal, then as now, is for our posivite energy to activate constant elevation; to intentionally cultivate an appreciation for something we've been down on.

{PiNK SMOKE PODCAST: PETERLOO}

{THEiR EARLiER STUFF WAS BETTER}

{SPALL OR NOTHiNG: PART 1}

{SECOND CHANCES: CAREER GiRLS}

{MiKE ON A BiKE}

The First Chance:

CAREER GiRLS

mike leigh, 1997.

“I’m not an idiot. I’m like an idiot savant, I just haven’t found my savant yet.”

I came to Mike Leigh late. For whatever reason (if there was even a reason), when I was a budding high school cinephile I decided I hated Secrets and Lies. I have no idea why - I honestly can’t remember. It definitely didn’t have anything to do with the film itself because I hadn’t seen Secrets and Lies. I did hate all of those movies about miserable British people and, sure, it seemed like Secrets was more of that. I hated the ones I had seen, anyway - which at that point probably meant only Saturday Night and Sunday Morning and Ladybird, Ladybird.

But there wasn’t anything notably rational to it. I just decided I hated this movie I hadn’t seen and couldn’t differentiate its director from a slew of British filmmakers (Ken Loach, Alan Clarke, Stephen Frears, Bill Forsyth) whose work I was convinced I wouldn’t enjoy. Obviously those filmmakers don’t have a hell of a lot in common and I was being an idiot, but this is a 17 year-old living in farm country Pennsylvania you’re talking about. I had just been made aware of Yojimbo, like, a couple months earlier. Hell, I had just been made aware of A Fistful of Dollars a couple months earlier.

So if I didn’t see Secrets and Lies, which I hated for no reason, I probably wasn’t going to see its immediate follow-up that had been greeted with a harmony of critical disappointment. And I didn’t. I didn’t see it until years later after I had become the World’s Biggest Mike Leigh SuperFan. I suspect if I had seen Secrets and Lies as a teenager and expedited my process of becoming a SuperFan, if I had seen Career Girls when I was better able to convince myself to like or dislike an artwork, then I have a suspicion I would’ve been willing to go to bat for it back then. If I had been a teenage Mike Leigh aficionado and apologist, I would’ve made a real effort to talk myself into it, the way I did with bad films from great directors I admired like Godard’s 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her... or Pasolini’s The Hawks and The Sparrows. Those are movies I was convinced I liked!

It wouldn’t have been hard to find an angle for giving Career Girls a pass - it’s a very Mike Leigh movie. Mike Leigh most definitely. Terrence Rafferty wrote of Life is Sweet’s startling emotional climax that emerges from the film’s seeming dramatic, narrative chaos: “And we realize, too, that Mike Leigh’s unusual filmmaking process is designed to generate scenes like this, to bring forth acting that is as pure and direct as Steadman’s and Jane Horrock’s.” That unusual filmmaking process and "chaos into clarity" design can be felt all over Girls.

A great film like Life is Sweet could only be the result of Mike Leigh’s devising and directing - a terrible one like Career Girls could only be the result of the same process. His best work has a chaotic quality that threatens to never quite come together, shaggy dog stories that never seem to be getting to their mysterious point, until miraculously, they do. Career Girls might be the one example of his work struggling to find its form and never discovering the moment, the scene, the character, the idea to make its inchoate elements coalesce.

When I finally saw Career Girls, the main problem I had with it was that I felt like the parallel story-lines, the disparate time periods just didn’t connect. It's a film divided into "now" and "some years before" that run along parallel tracks. But the younger and older versions of the main characters (Katrin Cartlidge and Lynda Steadman as the college students turned professionals of the title) didn’t seem like the same people; the two timelines felt like different, wildly incompatible films. It’s the one Leigh film I can think of where the audience asks itself “where is this all going?” and the film doesn’t communicate a satisfactory answer. The chaos generated by Leigh's process stayed chaos in a weird way: two separate, mediocre Leigh films slopped together like black-pudding-and-camembert soup.

Another set of tics that Leigh’s process can produce are literal tics: sometimes his creative process results in characters that are collections of overbearing mannerisms, repetitive physical actions and bizarrely idiosyncratic vocal gestures. When these acting mechanisms function properly, it produces performances like Timothy Spall in Life is Sweet, Alison Steadman in The Short and Curlies or Tim Roth in Meantime. When the machine goes haywire, it spews out the chortling, snorting cartoon villain of Naked (played by Gregory Crutwell), Alison Steadman’s weird simpleton in Nuts in May or Katrin Cartlidge’s chirping, hammy younger self in Career Girls.

And I want to emphasize again how different the two performances Cartlidge gives in this film are as the film jumps between two eras. The character on one timeline (at university) and then on the second timeline (taking place six years after college) just doesn’t seem like the same human being. It’s a shame because I adore Cartlidge and her squrrielly naif in Leigh’s Naked is one of my all-time favorite performances. But she's hardly the film's worst offender.

Career Girls features the absolute worst example of Mike Leigh’s penchant for portraying inarticulate characters locked in an unidentifiable position within a triangle of stupidity, developmental disability and insanity. Examples of this kind of character include Ewen Bremner’s “Maggie!” obsessed lout in Naked, the Rubber-Knocker Man in Happy-Go-Lucky, Tim Roth in Meantime, or the returning solider in Peterloo. These characters frequently skirt the edges of good taste1 and I have no defense whatsoever for Mark Benton as the mumbling, semi-sagacious street-yeller Ricky Burton in Career Girls.

That’s what’s so strange: the things that don’t work in Career Girls had all worked for Leigh in the past - the risks he takes with the film had consistently fallen in his favor previously. He must have been shocked to make such a stinker.

The only elements of the film that I can recall (and it has been almost a decade since I’ve seen it) as standing out for being atypical for Leigh are the fractured timeline and the terrible score. The music on the film is co-credited to Secrets and Lies star Marianne Jean-Baptiste and it is just the worst Lite Jazz nonsense. In talking about the film, I’ve frequently said that fixing Career Girls might be as simple as putting one of Andrew Dickson’s regular scores on it. If the film sounded like Naked, Secrets and Lies or Vera Drake, that might be enough to elide all the other issues I had with it.

Because, ultimately, the film feels wrong. It resembles a Mike Leigh film but the tone is all off. Music can go a long way towards steadying tonal imbalance and whatever chance the film might have had for working is killed (entirely to death) by the awful airy Lite Jazz warbling polluting the soundtrack. And I don’t enjoy saying that because Marianne Jean-Baptiste couldn’t be better as an actress. She literally couldn’t do a better job at the profession of acting. It’s not possible.

Why Give it Another Go?

I’ve been meaning to give this one another shot. I bought a DVD of it from a Blockbuster video that was going out of business, so there it is. On my movie shelf. Staring me down. It’s literally in the periphery of my sightline as a I type this. Shaming me. “Oh, the World’s Biggest Mike Leigh SuperFan is only going to watch me once and then decide he’s never going to give me another shot? Fuck you, Chris. You’re no SuperFan.”

Anyhoo, it’s Mike Leigh Month here at The Pink Smoke so what better time will there be to give the film another shot and see if I got it wrong? There’s a meaningful chance that because every other film Mike Leigh made from Life is Sweet to Mr. Turner is unalloyed genius (0% manganese & nickel)2 that I just had too high of expectations for Career Girls. I mean, I expected it to be one of my favorite films ever made since every other Mike Leigh movie from that stretch is.

Maybe it’s just ok and maybe the Lite Jazz is actually more Quiet Storm, something I can appreciate as I grow old and mellow and tenderly melancholy.

The Second Chance

Naked is outlier in Mike Leigh’s career: an episodic, nocturnal odyssey about a loutish, implacably restless young adult. Mike Leigh included unhappy teenagers throughout his work and even looked at young adults with some frequency, but he didn’t make another film focusing so directly on an angst-riddled hyper-intellectual outsider in his early adulthood.

Watching Career Girls this time, if I could contort it enough, I saw it as an attempt to return to the territory of Naked. They’re separated by only 4 years (1993 vs. 1997) with a single film seperating them in Leigh's output (Secrets and Lies) so it’s not unreasonable to speculate that maybe that’s where Leigh’s head was at and that he wasn’t quite done with a milieu that he never dealt with meaningfully before or after.

There’s a certain early 20’s sexiness and scuzziness to both Career Girls and Naked that I’m hard-pressed to identify in any other Leigh’s work. Both films are about greasy young adults aging painfully out of punk adolescence; their unhappy, muddled, desperate intellectual and sex lives. Both films feature sex scenes in cramped flats followed by painfully awkward mornings after. Casual sex rarely factors into Leigh’s work - or at least, not with the directness3 of these two films. The (consensual) sex scenes in both films are grimy and realistic, light-hearted and desperate, fun and ugly.

Both films feature a cartoonish yuppie prig bent on having sex with women who clearly don’t want to have sex with them.

They’re films about abrasive people, films in which abrasive people are meant to be the protagonists without any concern about whether it’s possible to like them or not. The main characters engage in weird vocal inflections, make strange jokes, behave in ways that are off-putting by any standard and the films assume that the audience will accept following their stories.

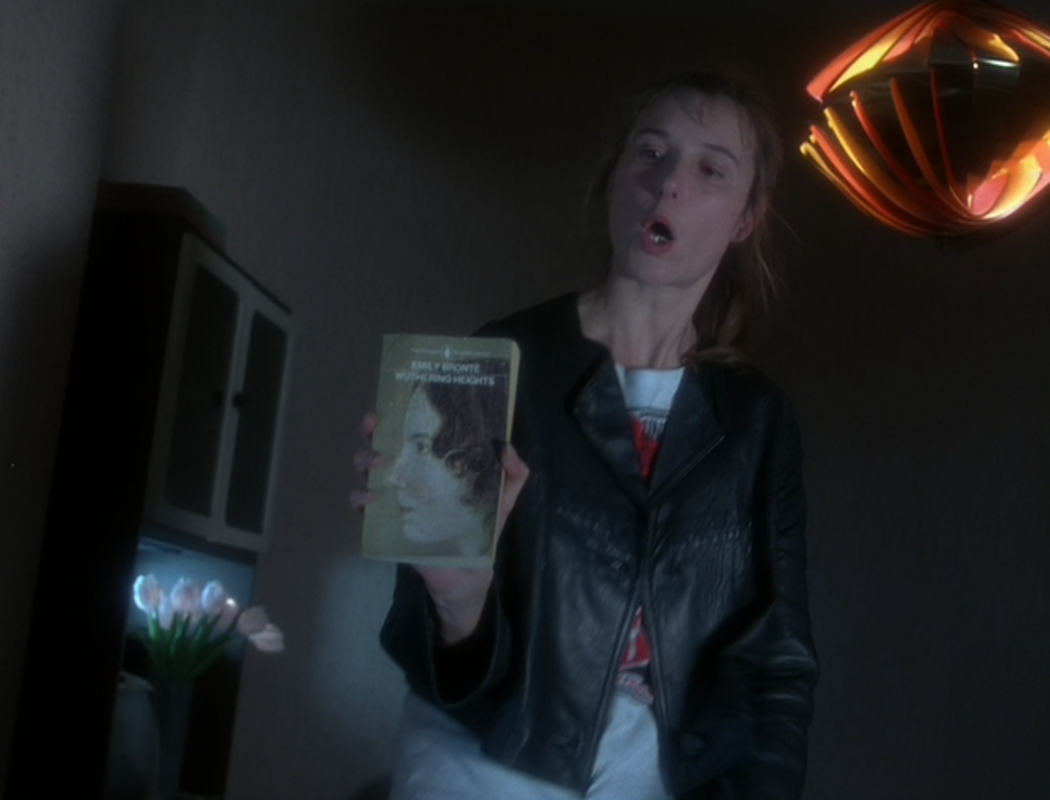

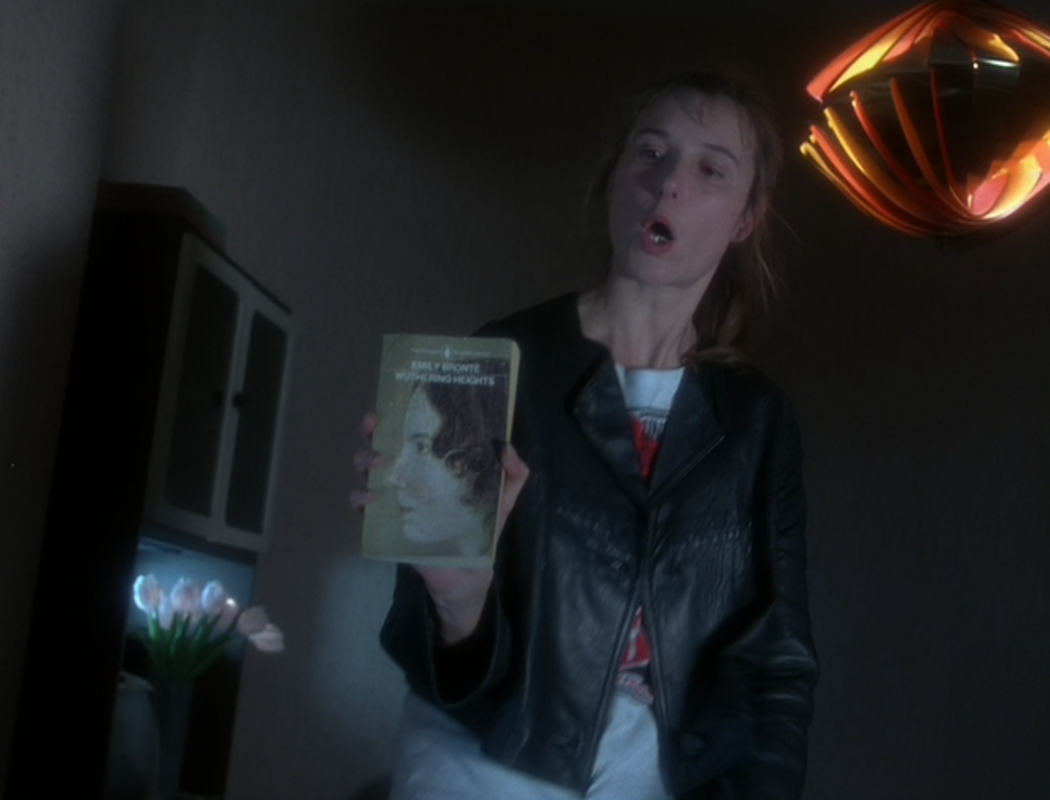

Both Naked and Career Girls have a fondness for near-impenetrable verbosity and puerile wordplay. In Naked, Johnny says, “Is the home owner sexual?” and in Career Girls a cad asks if one of the girls is “looking for a new erection [instead of direction].” And I don’t know what it is but something about Naked’s Johnny saying “Jane Austen by Emma” reminded me of the career girls chiming in unison “we’re the Bronte sisters, we always get the Bront of everything” - just like Cartlidge's character seeing a skull and exclaiming “is that my mum!?” reminded me of Johnny pointing at a medical chart and asking if that’s the unseen roommate Sandra.

“Touching time with a 10 foot pole, I wouldn’t,” is the kind of line that could be in either film; the semi-sarcastic use of Wuthering Heights as a fortune-telling device is the kind of absurd and goofily intellectual concept Johnny could’ve forced on some poor doorman or chip shop proprietor. The younger versions of the career girls unquestionably could've gotten caught up with a character like Naked's dyspeptic, restless Johnny.

Leigh agrees; as reprinted in Faber & Faber’s Leigh on Leigh, he told an interviewer, “And from a writing point of view, you might consider it alongside Naked and Topsy-Turvy. It has a dialogue style quite unlike that of any of my other films.” The rambunctious factually-inspired period drama Topsy-Turvy was at the time of the interview another major anomaly in the filmmaker’s career - though with recent additions of Mr. Turner and Peterloo to his body of work, it feels far less out of place than it did even 10 years ago. There’s still nothing quite like Naked in his oeuvre.

Story-wise, Naked and Career Girls are Leigh’s most direct. Both films amount to a series of episodes that don’t necessarily build on one another (not in the way they do in Leigh’s other work) and the films aren’t structured around ensembles. They don’t digress to a point where (as with, say, Life is Sweet or All or Nothing) you’re unsure which two or three people might even be considered the main characters. There's no question Johnny and Girls' Annie are the main characters of either film. While it's not entirely out of character for Leigh to have a main character proper (as in Happy-Go-Lucky or Mr. Turner), the examples in which he gives multiple characters and narratives threads equal berth far outnumber the more traditionally protagonist-oriented films.

From a general story perspective, they're simpler than either Happy-Go-Lucky or Mr. Turner: Career Girls, like Naked, follows an unsettled character going to London to see an old friend who is settled into their life there. To try to describe virtually any other of his theatrical features in such straight-forward terms would be a dipshit's errand. But in a way that isn't fully concrete, there’s something that one this viewing tied Naked and Career Girls together to me. The great outlier of Mike Leigh’s career resembling his most wretched failure makes sense on some level.

Because there’s no getting around it.

Naked is one of Leigh’s most overwhelming artistic achievements. And Career Girls is awful.

But watching it again, I spent most of my time trying to understand what it was Leigh meant to accomplish - so I ended up with a kind of sympathy for Girls that I definitely didn’t feel before. Maybe seeing Cartlidge, who died suddenly at age 41, made me sentimental but Career Girls is a film that I wanted to understand. I wanted to give Leigh and Cartlidge their full due. I'm not sure if I found any crag in which my sympathy could find satisfactory purchase, but I wanted to. Maybe I got it flipped, maybe as a teenager I would've been hard on a plainly bad film and now as a middle-aged man I want to feel the intent of an artist I admire even in his failures.

Let’s start with the music, which is even worse than I remembered and I remembered it being it being a fucking disaster. It hits you in the face, in the very first scene as Lynda Steadman’s Annie stares out the window on her train-ride into London.

Sensitive guitar noodling.

Calling it Lite Jazz might not even be the correct term for it. Adult contemporary? It’s strictly Muzak-grade call-waiting audio terrorism and it kills the movie from the jump. I have no idea what Leigh was thinking… apart from the fact that the star of his break-through film, Secrets and Lies, had composed it. Leigh’s reputation is not of a sensitive or kind man, but it’s easy for me to be sympathetic to the sentimental urge to collaborate again with Marianne Jean-Baptiste after their life-changing experience on Lies.

In the Faber book of interviews with Mike Leigh, he more or less confirms my sense of it: “We were on a plane in America doing a promotional trip for Secrets & Lies, and she was saying how much she'd like to write music for films. So I got her to do it for this. It's so unlike the music from my other films - which seemed very right.”

It’s a mistake that unequivocally ruins his movie, but like I said, I’m sympathetic to it. If I look at it through one split of the prism, it’s a human mistake - not an artistic one. And I can get behind a human mistake. There's something forgivable, even touching, about such a terrible artistic choice being sourced from sentimentality, fraternity or professional respect.

It’s harder to understand his casting of Annie. Lynda Steadman didn’t have much of a career before or after this one and she doesn’t do anything to make you feel like she’s some marvelous untapped talent. The film positions her as the star, or at least angles the story from her perspective - but she gets blown off the screen by Cartlidge’s Hannah over and over. She just can’t hold her own. The choice to make this Annie's story and not give quite equal weight to Hannah is a miscalculation I have a hard time understanding. Leigh's expertise is in ensembles, so you'd figure (I'd figure at any rate) that on the rare occasion he chose to focus more directly on a main character, he'd have a really good reason to do so (like Sally Hawkins' show-stopping turn as Poppy in Happy-Go-Lucky or David Thewlis' truly jaw-dropping, Cannes-feted frog splash of a performance in Naked.)

But even if Steadman weren’t set opposite an incredibly forceful and inventive and just plain weird actress like Cartlidge, it’s hard to imagine her performance commanding the attention Leigh points towards it. As a college student, she’s plagued with splotchy dermatitis on her face that causes her to be socially awkward and as an adult she’s an ultra-bland mousy secretary type. She goes from pink hair, black fishnets and a Taxi Driver poster on her wall to an undifferentiated mass of human beige.

Like I said, the film has real trouble connecting the younger and older versions of these characters and Annie just doesn’t feel like the same person. Steadman’s mannered, over-the-top performance doesn’t help. My sympathetic eye sees this as Leigh exploring the ways in which we change over time and how different we can become from our college self, but my regular audience eye just rooollllls back in my head and says “what is this bullshit?”

Steadman plays the younger version of Annie like one of the Kids in the Hall in drag - she’s a brittle, head-bobbing caricature. When she’s playing a Cure-loving college weirdo, she reminds me of one of Bruce McCulloch’s dingbat housewives. The dermatitis is weirdly unconvincing - it’s too much by any measure, an example of the kind of “physicality in place of characterization” that bad actors love.

In terms of Leigh’s work, the dermatitis is a cousin to piling on the verbal tics, but it's an artistic strategy Leigh rarely engages in: Jim Broadbent in A Sense of History aside, Leigh doesn’t usually go in for prostheses and radical make-up when working with the actors (which is somewhat surprising considering his reputation for overseeing the creation of layered, transformative performances.)4 Leigh's use of physicality in performance is notable so it's equally notable how he eschews having actors get very fat or very thin, put on old age make-up or prosthetic noses, walk around with club feet or knee-braces. Leigh definitely doesn't encourage his actors to chase after "he gained 60 pounds for this shit!" or "beautiful lady is not afraid to get ugly!" notices.

There’s an even wider gulf between Cartlidge’s greasy, mumbling, poorly dressed college self and her articulate, stylish, ravishing businesswoman. Her transformation is somehow even more radical without the use of faked up scaly skin. In a general way, there’s something off about how totally both characters transform into entirely different, utterly unrecognizable people. Again, I think this is a theme that Leigh wants to explore, but it just isn’t convincing. It’s weird, almost to the point where it feels crazy for the audience to believe that these two sets of women have anything to do with each other.

In my experience, people don’t just drop their physical and verbal tics altogether and I’m hesitant to believe that both women might so totally reinvent themselves in terms of how they dress, speak and behave. Narratively, though, the film has this change on its mind: they run into an old boyfriend (a Morrissey-aping lout named Adrian who bedded Hannah before quickly switching over to Annie) and he doesn’t have the faintest clue who either of them are.

I’m not sure what the film wants me to take from that. Annie seems hurt that Adrian doesn’t recognize her, but who in their right mind would? They don’t recognize him until he says his name, in any case. There’s something deeply off about the film in terms of how it seems to expect the audience to be taking what's on screen - there was a gulf at all times between Annie’s sensitive and tearful reactions, the saccharine & sentimental soundtrack, the fraught looks shared between women and what I was feeling or thinking about any given scene.

At one point, the fully adult versions of Annie and Hannah pretend to be interested in buying a fancy/schmancy apartment and have to contend with the flat’s horny, coked up yuppie owner (played by Andy Serkis.) At the end of this unremarkable sequence, the duo hustles out to the elevator and laugh like something incredible has happened… and keep laughing… then it cuts to a follow-up scene in a car… and they’re still laughing. But nothing particularly interesting has happened.

Either these characters are boring and they have no idea of it or the film is boring and it has no idea of it.

As I mentioned, the plot is incredibly straight-ahead for Leigh. I want to say this is by design on Leigh's part. Annie arrives in London to spend the weekend with Hannah. They go to see some apartments and have dinner. Along the way they run into people who were major figures in their shared past - and we (sorta) learn why these people are important via flashbacks peppered throughout the film.

That’s it: Annie shows up, apartments, dinner, done. Explanatory flashbacks interspersed.

There’s very little story and very few characters in the film, so the coincidence of them running into their ex-boyfriend, ex-roommate and ex-Ricky feels even lazier. The film displays almost no effort or thought in terms of its over-arching story construction - it’s content to replay the same unlikely coincidence over and over in embarrassing repetition.

It’s startling in contrast to Leigh’s usual deftness with cagey and unpredictable storytelling - part of his slyness as a storyteller is that you can’t possibly guess where he’s going with any of it. His films feel messy and chaotic as an intentional strategy - they catch you off guard and knock you around emotionally from unexpected directions. Career Girls seems to throw up its hands and say, “Whatever... so then they run into the guy that was in the flashback you just saw.”

The film constantly calls attention to these unlikely coincidences, the Hack’s Method for waving off unconvincing screenwriting. “Coincidence is one thing, but this is a joke, innit?” says Hannah when they run into their inarticulate, possibly mentally ill friend Ricky. It’s such a dry fart of a method for how to deal with the film’s many blatant narrative conveniences.

Leigh has defended the coincidences by saying he intended for the film to be “ethereal” and “spooky” - that he meant for Ricky to be “actually haunting the place” when he’s found hanging around outside the chips-shop. But these scenes couldn’t be more prosaic. There’s no hint of cosmic mystery to them, no magic seeping into the traditional Leigh realism - and I can’t buy Leigh’s post-facto explanations for his intentions when the film itself is so defensive about it unlikelihoods.

The script just won’t let it go, it even ends with this exchange:

“Think they’re be any more coincidences on the train?”

“I dunno, maybe you’ll meet the man of your dreams.”

Roll credits, kicking in with sensitive guitar noodling. It sucks so fucking much.

At 87 minutes, it’s easily Leigh’s shortest theatrical feature film. His movies tend to run on the long side - most clock in over 2 hours and even the breeziest like Happy-Go-Lucky or Life is Sweet still manage to push towards the long side of the expected length for a theatrical release. It’s a film that feels a little like Leigh gave up on it, that somewhere in the process he discovered he had less to say than he thought and the result feels unfinished - or maybe like the work of a disengaged artist who can’t pretend to be interested in a bad piece that isn’t working.

The short running time plays like a final gesture of “well, I give up - here’s something that meets the bare requirements for release.” Normally, a Leigh film navigates chaos; they intentionally create a narrative mess from which themes, emotions and relationships emerge gradually. By attenuating the process, that process of gradual emergence feels utterly incomplete. The shortness plays like a failing.

In interviews, Leigh has indicated the short running time was agreed upon before he even began work on the film; it’s brevity, small cast & simplicity baked into the concept: “In spring 1994 Simon and I went and drank a bottle of wine with [BBC producer] George [Faber] and made a gentlemen's agreement that we would make a ninety-minute film… It was shot in five weeks and we only had six characters. I didn't do a long casting process: I just cast people I knew and got on with it. We wrapped it before going to Cannes with Secrets & Lies in May 1996 and then came back to edit it.”

It seems strange that we would throw out his usual process, but there was also behind-the-scenes conflict with the BBC originally fumbling a gentleman’s agreement to make the film and it being picked up by Channel 4 instead - that easily could’ve contributed to the muddled end-product. And in the same interview, Leigh seems to be thinking of the film in different terms than he does his full features, “In the healthy traditions of an experimental short story, it falls between weightier major novels and historical reconstructions - it has a lightness and freedom and fresh air that I'm pleased with.”

I mentioned the strange disconnect between what the film is asking us to feel and what I felt while watching it - it’s a disconnect that somehow feels tied up with the film’s surprising brevity. It’s a film that I wish digressed more, a film that I wish included both more scenes that had nothing in particular to do with the story and also more scenes that pointedly flipped and reversed expectations.

None of the relationships feel fleshed out, even the central duo of Cartlidge’s Hannah and Steadman’s Annie. They’re roommates, sure, but beyond that I wouldn’t know how to categorize how they feel about each other or what they mean to one another. None of the Big Moments in the film have any impact because we haven’t gotten to know the characters the way we do in the rest of Leigh’s work and it’s easy to point at the running time as an explanation for the thinness.

The film feels like it needs another 10 minutes spent on Ricky, another 5 minutes spent on Adrian, another 15 minutes on the basically forgotten 3rd roommate Claire (who is so inconsequential to the film that I haven’t had any reason to mention her yet.) With the exception of Claire, the relationships between all these characters don’t make sense and must be pieced together in a weird shorthand at odds with the rest of the narrative’s lumbering straight-forwardness.

It’s a film that slows down to explain things to the audience that don’t need explaining and rushes over the confusing bits.

The film wouldn’t be hurt by, say, having more about why Ricky had to move in with Hannah and Annie, more of their adventure trying to find him in Hartlepool, a few more simple scenes of the trio hanging out. It’s painful to say so because I don’t actually want any more of Mark Benton’s hammy performance5 in my life, but the film needs to bolster him meaningfully.

The scenes that come closest to working (in the way a typical Mike Leigh film works, I mean) are the ones at the end featuring a pathetic, disoriented Ricky; there's one where they find him hanging out at the since-closed Chinese chips’n’curry shop and then another one featuring his drunken seaside tirade against the well-meaning young women. With a little more work on elucidating the relationship between these three characters, those scenes could have had a real impact.

For example, when a broken-down Ricky accuses Hannah of never having liked him, I had no idea if that’s true or not. It wasn’t something the film had explored. I had no sense of it one way or the other so I just had to take Hannah at her word when she mumbled to herself “that’s not true, actually.”

Again, it’s a moment where the film explains what would normally be felt in any other work by Leigh - Hannah has to tell the audience how she felt about Ricky because it’s just not made clear. The worst example of this problem (a scene that has to be the film’s hallmark failure) comes during what feels like it should be the centerpiece of the movie: a meandering conversation about the past and the present as Hannah and Annie have dinner at a Chinese restaurant.

After running into Adrian, they sit down for a meal and process their lives head-on. What’s so strange about this scene is that they express their emotions in a thuddingly straight-forward way; one literally says, “I’m too vulnerable” and the other says “I’m too independent.” It’s the kind of emotional idea that Leigh usually expresses dramatically, if he’d even go in for that kind of simplistic symmetry to begin with.

“Show, don’t tell” is what they tell ya, but it’s advice that Career Girls is constructed on ignoring. The ideas and relationships of the film feel underwritten so the dialog keeps explaining to us what it can’t get across. “I am this kind of character who feels this sort of thing for these reasons.” Hannah’s alcoholic mother comes up over and over again (and her too-perfect sister is mentioned in passing) but we never meet the mother and the impact of her behavior on Hannah is strictly something we have to take Hannah’s word for. Same for Hannah’s supposedly screwed-up relationships with men.

The scene in the Chinese restaurant contains the worst of this kind of emotional exposition, the apogee of the film’s tendency to have dialog stand in for drama. It’s a scene that means nothing, evokes nothing in the audience and features sadly amateurish writing. It’s like every bad one act play you’ve had to misfortune of seeing.

It’s crazy that Mike Leigh had anything to do with this scene.

I can’t get over it.

As much as I can see Mike Leigh in Career Girls or find ways to connect it to the other great outlier in his work, it’s still a film that mystifies me. No one could have made this movie but Mike Leigh. And even though its problems recall the more unsteady or questionable elements of his best work, I still can’t understand what the hell went wrong.

From the beginning, his eyebrow-raising “devised and directed by” credits and proprietary script development process have created an aura of mystery and intrigue around Leigh’s methods; his singular brilliant work the result of something inscrutable and strange. Career Girls is the one time that process failed him entirely… which makes what happened even more of a mystery.

~ APRIL 16, 2019 ~

1 Their existence is obviously the result of a performative, actor-ly process and, at their worst, that can make them feel a bit like the expression of an actor’s narcissism more than an honest exploration of a psycho-physiological condition. What I’m saying is, Mike Leigh encourages his performers to go full retard and that can be a dangerous, cringe-inducing gamble.

2 Some of you reasonable readers probably thought, “Doesn’t he mean the run from Meantime to Mr. Turner?” And I thought about it. I did. I agonized over it. Ag. O. Nized. With which film does Leigh’s run of genius begin? Aren’t High Hopes and Meantime brilliant? They are. I just think Life is Sweet is the turning point, the first True Mike Leigh Movie, the one where his shooting style finally leaves the teleplay blandness behind and his aesthetic choices take a subtle but major leap forward. Meantime and High Hopes are great, they just feel transitional to me: they’re part of the process of him casting off his earlier, unremarkable blocking and editing style.

3 I’m hard pressed to think of sex scenes in his work beyond All or Nothing or Happy-Go-Lucky. So maybe it’s just a Sally Hawkins thing. Beyond that, his period pieces have a couple of gross/weird sex scenes set in brothels. And sticking to themes, as in Naked and Career Girls, Cartlidge appears in the sex scene in Topsy-Turvy. On the other hand, neither Hawkins or Cartlidge appear in Mr. Turner, so that shoots that theory to shit. But it does feature more scuzzy/depressing sex scenes with Timothy Spall and his maid played by Dorothy Atkinson… who like Annie, has a skin disease. So, there you have it: a incomprehensible muddle of evidence in support of a half-thought-out idea. There's also the Nutella-sex in Life is Sweet, which like Career Girls also features a young woman with unshaven armpits. Case closed.

4 Interestingly, and maybe undermining my point a little but, Topsy-Turvy won an Oscar for Best Makeup. Even still, the makeup in that film isn’t exactly the of transformative work that dominates that category - for comparison, it beat out Austin Powers 2: The Spy who Shagged Me, Bicentennial Man and Rick Baker's work in Life. While the makeup work in Topsy-Turvy doesn't seem notably better than the work in those films, I just assume they made the decision to give the award to an actual good movie rather than a stupid piece of crap. Closer to your point (person who is arguing against me that Mike Leigh avoids makeup effects): Dorothy Atkinson’s character has psoriasis in Mr. Turner - but that’s a combination of character and makeup effect that works notably better (especially in terms of subtlety) than Steadman and the dermatitis in Career Girls.

5 To be fair, he’s not as bad as I remember him being. He’s just too much in a film that already features a handful of other characters going over the top.