MATHESON MONTH ~

john cribbs

This year we lost one of the great masters of genre fiction, the incredible Richard Matheson. Actually, "incredible" might not be the best word to use - Matheson always derided the film studio tacking it onto the title of his The Shrinking Man. But that's the kind of inevitable compromise a writer can expect when he allows his work to be run through the Hollywood wringer. The impact of Matheson's novels is inestimable, especially the part they played in shaping two popular horror subgenres: the zombie craze (Romero's Dead movies were inspired by I Am Legend, even moreso than the three muddled movie versions of that book) and paranormal investigation (would there have been an X-Files without The Night Stalker?)

But what about films sourced directly from Matheson's writing? All seven of his novels and several of his short stories have been turned into movies, some multiple times, and he was even more prolific as a television and screenwriter. Sometimes the result was visionary (Duel, his classic "Twilight Zones"), sometimes trivial (Loose Cannons, What Dreams May Come), often somewhere inbetween. Which is what The Pink Smoke intends to examine in this tributary series to the legend himself... up in this hell house, October is Richard Matheson Month.

THE COMEDY OF TERRORS

jacques tourneur, 1963

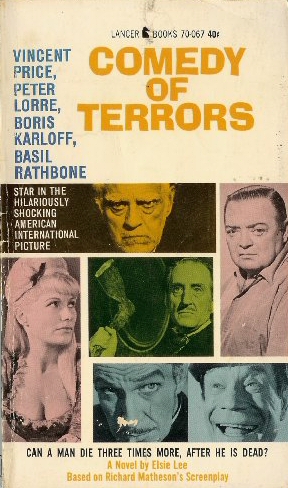

There's a reason you don't find "comedy" in the ARKOFF formula. Especially in the 60's, when AIP churned out such painfully unfunny, dated fare as the Annette & Frankie beach movies, Mars Needs Women and Dr. Goldfoot and the Bikini Machine and, following the consensus that the formula for Roger Corman's Poe cycle of films was running thin, 1962's tongue-in-cheek Poe portmanteau Tales of Terror and 1963's gag-laden The Raven. Both were scripted by Corman's go-to Poe adapter Richard Matheson; unlike fellow horror novelist William Peter Blatty, Matheson didn't come from a comedy writing background, so any derivable humor from these films came largely from the gimmick of seeing varying combinations of screen heavies Vincent Price, Peter Lorre, Boris Karloff and Basil Rathbone go head-to-head rather than any witty banter coming out of their mouths. All four actors came together the following year for the Matheson-penned The Comedy of Terrors, an even more aggressively broad romp with such cornball gags as high-pitched singing that breaks glass, fingers getting slammed in organ lids, bodies collapsing on broken chairs in fast motion, goofy behavior warranting befuddled double takes...be assured, if there's a row of marble busts perched upon wobbly podiums in Terrors, they will end up getting the domino treatment. The film even features a cameo by Joe E. Brown, the first half of the century's version of Bill Irwin, which makes the whole affair feel even more like a low-budget version of It's a Mad Mad Mad Mad World.

It wasn't the best epoch for comedy in general...by the 60's, Billy Wilder had almost single-handedly stamped out the brilliance of screwball comedies. Jerry Lewis' mugging sullied the memory of the great silent comedians, just as Jim Carrey would later for televisions stars who rose to big screen prominence in the 80's. The 60's ushered in the harmless mediocrity of Neil Simon, the pinnacle of Peter Sellers' ubiquitous stardom and loads of laughless Disney live-action "comedies." The horror genre wasn't exactly seaworthy itself in the first half of that decade - for every The Haunting and Repulsion, there were 100 justifiably forgotten B-movies. So while AIP scored a comedy-horror masterpiece in the 50's with Corman's A Bucket of Blood, the company's penchant for following popular trends led to infusing their antiquated horror yarns with schlocky comedy in the 60's.

That might not have even been a big problem for the movie - its most irritating antics are on par with those of Polanski's hardly intolerable Hammer Horror send-up Fearless Vampire Killers - but moreso Terrors suffers from the forced "fun" atmosphere of the film, reflected in its publicity stills, which the sad physical presence of its iconic stars can't make convincing. Lorre is depressingly fat and tired, Rathbone sort of off in his own world, Karloff looks old and remains largely unengaged in the action (although, to be fair, he is playing a senile old man) - all three actors would be dead within six years following the film's release. It's not quite the grotesquerie of, say, Richard Pryor in Lost Highway, but the casting is certainly no less exploitive than Ed Wood's use of post-stardom Bela Lugosi. So while the comedy isn't quite as excruciating as it is in The Raven, the enjoyment of seeing these actors together is also not nearly as novel. As cheesy as it is, it's fun to observe Price and Karloff having a sorceror's duel, or Lorre walking around with absurdly giant black wings for arms, with a knowing detachment further informed by Corman's clear reverence for his B-movie cast. But with each perceptible sigh from Lorre or rousting of Karloff to bellow a line (again, I realize Lorre's character is despondent and Karloff's nearly comatose but it all reads poorly), you have to wonder if, just a year later, the gimmick of "Get it? Price and Lorre out-creeping each other!" had so suddenly dissipated. (Honestly Terror's biggest star may have arguably been the prolific Orangey the cat, who had a supporting role in Breakfast at Tiffany's and went on to win two animal Oscars - seriously!)

All that said, Terrors is uniformly better than The Raven. For one thing, it resembles an actual movie with an actual story and characters - as worn out or wired as everyone in the film appears, they never seem like they're just standing around a cheap set. If it suffers from a lack of gratifying "hanging out with enjoyable actors" time, it may be because the attitude on this production was "let's get serious and make a movie here, guys." It's strange to accuse the filmmakers of being unreasonable for requesting that their actors, y'know...act, but Matheson's script and the rigid direction often demand more than its cast can offer, and the lack of energy really saps the movie of some much-needed strength. The major exception is Vincent Price, who carries the film upon his smug shoulders and looks like he's having a great time doing it. Lorre gets the most pratfalls, Karloff plays the fiddle and gives a rousing performance of a muddled obituary, and Rathbone runs around with an axe emoting Shakespeare, but even slouched across a table stone drunk Price emits more vitality than all three combined.*

I'm not a big Vincent Price fan, but he excels at playing delightfully amoral con men: the ambitious mountebank you end up rooting for in Sam Fuller's Baron of Arizona, the lecherous holy hypocrite you love to hate in Michael Reeves' The Witchfinder General (aka The Conqueror Worm - seriously, how often does a movie get two awesome titles?), and let's not forget his portrayal of one of history's most successful charlatans, Joseph Smith, in Henry Hathaway's Brigham Young. In Terrors he's the unscrupulous proprietor of a fledging funeral home: he's used the same casket for 13 years, hasn't bothered to embalm a corpse in six, and yet still finds himself 12 months behind on the rent. This forces him to actively seek out new business by paying nocturnal housecalls to elderly rich folks who might require a little assistance moving on. He brings along reluctant assistant Lorre, under Price's thumb due to certain "illicit sundry peccadillos" from his past - their relationship is similar to the Zero Mostel-Gene Wilder duo in The Producers,** with timid Lorre fretting and boorish Price eager to smother his way out of a life of cardboard belts.

Matheson manages to shift audience sympathy to Price's unrepentent murderer, who between snuffing out sleeping millionaires verbally abuses his wife and "jokingly" attempts to poison his father-in-law (Karloff) at every turn, by the character's simple industriousness: he may be a cad, but he's the only one trying to creatively - albeit homicidically - stay afloat in a tough economy, as much a survivalist as I Am Legend's Robert Neville or Scott Carey's shrinking man. He's charmingly misanthropic, boozing it up and crooning about "rapping gently with a hammer on a baby's skull," but is constantly thwarted by the greed he unknowingly awakens in others. In the best scene of the movie, he arrives at a mansion to collect from the busty young trophy widow of his latest victim only to find that she's taken the money and run, leaving nothing of value behind in the house or even bothering with the maid's final paycheck. A malevolently righteous glow - incongruous with the windowless interior - envelops him, as if god himself is enjoying the cruel irony.

Price finally catches a break when his new plan to kill two birds with one pillow results in excitable landlord Rathbone suffering a stroke and seemingly dying. But nobody lets Price and Lorre in on Rathbone's flawless impression of a dead person, and before long the film slips into a string of vignettes with the perturbed morticians chasing and being chased around the funeral parlor by their cataleptic customer. With this hijinx, Matheson smartly marries a Shakespeare staple - the comic confusion ensuing from a character wrongly believed to be deceased (see: Cymbeline, Twelfth Night, Much Ado About Nothing, Measure for Measure and, with more tragic consequences, Romeo and Juliet) - with the common Poe device of live interment. Unlike the unnamed narrator of "The Premature Burial," Madeline Usher or Berenice, Rathbone jolts from his pseudo-cessations robust and psychotically vengeful (he was in the middle of performing both sides of Macbeth and MacDuff's final duel when he initially "died," prompting him to take up axe and seek theatrical retribution on his would-be undertakers). This leads to what is easily the movie's best exchange, when Price and Lorre are hiding in a room as an axe-wielding Rathbone gives a door the ol' Jack Torrance treatment and Lorre blows out a candle:

Lorre: It's better in the dark!

Price: What is, decapitation?

The film ends in a series of parodies of Shakespearean deaths (star-cross'd lovers Lorre and Joyce Jameson seemingly dying side-by-side, an erringly-imbibed flask of poison standing in for the goblet Gertrude unwittingly gulps down in Hamlet) that punctuate the script's thoughts on the fickle nature of death. I already mentioned how much Price's impish energy brings to the movie and how his unorthodox approach to dealing with a slumming funeral business comes off as weirdly defiant and industrious - he refuses to lie down and die so he decides to go out and make others lie down and die - and the absurdity of Rathbone's Rasputin-ian revivals bring about an existential frustration. "Everyone else knows you're dead except apparently you," he complains to Rathbone, doubly accusing his rival of refusing to "cooperate" by simply dying, a stubborness Rathbone is hardly aware of compared to Price's arduous conniving and struggle to stay afloat (like the widow who took advantage of Price's murderous plot), and for holding onto a life Price doesn't consider worth living in the first place. If Rathbone is the Bugs Bunny of death, effortlessly avoiding its cold grip, then Price is its Daffy Duck, pointing the shotgun at others only to have his own beak blown off. Price, who would survive his co-stars another 20 years, is the only one of the leads who doesn't have death hanging over him yet after impotently failing to murder everyone else is the only one who ends up dead, literally getting a dose of his own medicine. He needs others to die to avoid dying himself, yet for all his audacity and the endurance Price brings that the other actors in the film can't supply, the great cosmic joke is that death comes to him alone. So while it falls short of enough notable comedic moments like the decapitation line, Matheson's script finds humor in manic imbalance of life itself.

Another reason Price's character seems oddly sympathetic is that, short of actual murder, his approach to funeral home management isn't unlike Roger Corman's approach to filmmaking: re-using the same casket just as the B-movie maverick recycled sets and footage, coming up with solutions (murdering Rathbone) that take care of multiple problems and keeping a busty woman around despite her obvious lack of talent. Surprisingly however, Corman didn't direct Terrors - that duty fell to Jacques Tourneur, who'd already dealt with stubborn dead folks in I Walked with a Zombie.*** While Tourneur was well-equipped to deal with the horror half of the film, and Rathbone's resurrections do echo the question of "is it supernatural or mundane?" from the plots of Tourneur's films for Val Lewton, he may not have been the best candidate to handle the comedic aspect. According to Tourneur, he saw the movie as "a cynical, cynical comedy, a little bit in the old René Clair tradition." Hm...René Clair, cynical? "Cynical, cynical?" Tourneur may be more French than me, but I'm at a loss. I admit I haven't seen ultra-early Clair movies like Crazy Ray, but there's not even a scintilla of what could be considered cynicism in his most famous work. I guess he might have been drawing comparisons between Terror's team of down-on-their-luck-yet-lovable crooks to Louis and Émile from À Nous la Liberté, but otherwise I can't think of a least appropriate word to describe the very humanist films of the great René Clair (I even consulted with Funderburg on this and he agrees this is a crazy thing for Tourneur to say). So it stands to reason that a non-comedy director who finds Clair cynical would have difficulty locating an appropriate comedic tone to his comedy film, although again the script's take on cosmic injustice and Price's failure to have the last laugh suits the fatalism of Tourneur films like Nightfall and Out of the Past (Jane Greer: "Oh, Jeff, I don't want to die!" Robert Mitchum: "Neither do I, baby, but if I have to I'm gonna die last.")

Tourneur said of Matheson's screenplay: "For the first time in my life, I read a script and said, 'It's perfect, let's shoot it without changing anything.'" It's easy to see why Matheson's script would be considered a masterpiece: there's certainly an innovative black humor about it and colorful characters, but something got lost in the translation. Other than the comedy problems, it doesn't really deliver on the "terror" - the most macabre thing about the actual production is the obvious stunt double wearing a creepy Peter Lorre mask. It's a shame because the writer and director joined forces to create one of the most genuinely frightening Twilight Zone episodes, Night Call, which aired the following year. The simple story of an old wheelchair-bound woman receiving phone calls from the grave, Night Call also deals with the living's reliance on the dead and plays directly on how unapparent said reliance is. In Terrors, Vincent Price would just as soon everybody around him drop dead so that he can continue living, not realizing the symbiotic relationship between himself and death, which must logically conclude with his own. Night Call's Gladys Cooper, whose most fulfilling activity is a game of gin with her health aide, doesn't realize until the inevitable ironic ending that by unwittingly severing her link with the inanimate past is the final step towards her own death.

Matheson, also credited as associate producer on Terrors, suggested Tourneur for the film after working with him on 'Zone (the only episode Tourneur directed). It's easy to understand why the writer would want to bring the director onboard following their excellent collaboration, but while the heavy themes are all Tourneur the goofy comedy probably would have been more up Corman's alley. But then it would have just been another Raven - a good thing and a bad thing.

Matheson's screenplay was novelized by a writer named Elsie Lee, I'll have to check it out.

~ OCTOBER, 2013 ~

* Jeez, I feel like the grade school teacher who embarrasses the classroom's one competent student by announcing, "Everybody do like Vincent - Vincent's doing it right!"

** A better, if less universal, comparison would be Mark-Paul Gosselaar and Tom Everett Scott in Dead Man on Campus: two guys, one more reluctant than the other, trying to solve their problems by nudging a third party towards an untimely demise.

*** This is the only case of which I'm aware that Matheson - whose I Am Legend inspired Night of the Living Dead, which in turn inspired every damn zombie movie since - deals directly with the undead (Terrors was released the same year that Price starred in The Last Man on Earth, the first of many mangled versions of I Am Legend).