MEMORiES OF A LiFETiME:

ON THE SABBATiCAL HORROR MOViE

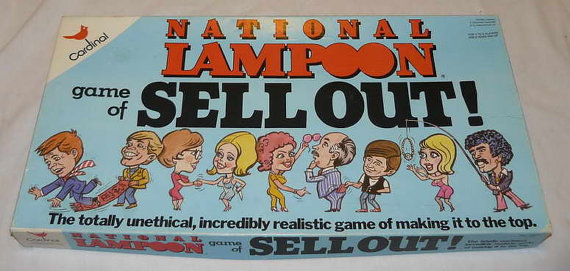

It's summer in October as The Pink Smoke looks at two films about traumatic summer trips that might not seem comparable at first but are connected by tropes of the vacation horror movie: 1976's Burnt Offerings and, naturally, 1983's National Lampoon's Vacation.

BURNT OFFERiNGS

dan curtis, 1976.

NATiONAL LAMPOON'S VACATiON

harold ramis, 1983.

~ by JOHN CRIBBS ~

~ with charles kinbote ~

"A tourist is crazy enough to eat its young."

~ Harry Crews, Body.

Everybody deserves a vacation.

Not just because a respite from the daily grind is crucial to maintaining one's sanity (although there's that too). Putting some distance between oneself and the normal routine, mentally and spiritually as well as physically, is a revitalizing act of self-realization: a chance to seek out uncommon adventures, perhaps achieve an unfulfilled goal, maybe even make up for something that got pushed to the side in favor of the perpetual and the mundane. To live a life free of regulation and responsibility, for a short amount of time at least.

That sort of gratification is important, but it's risky - how far down that holiday road can one travel without falling under its extricating euphoria? The longer and farther you're drawn away, the easier it becomes to sacrifice the held-fast foundations of life to pursue what is ultimately a fleeting event. Losing track of the transitory essence of a summer trip can have dire consequences. You could lose your mind. People could get hurt.

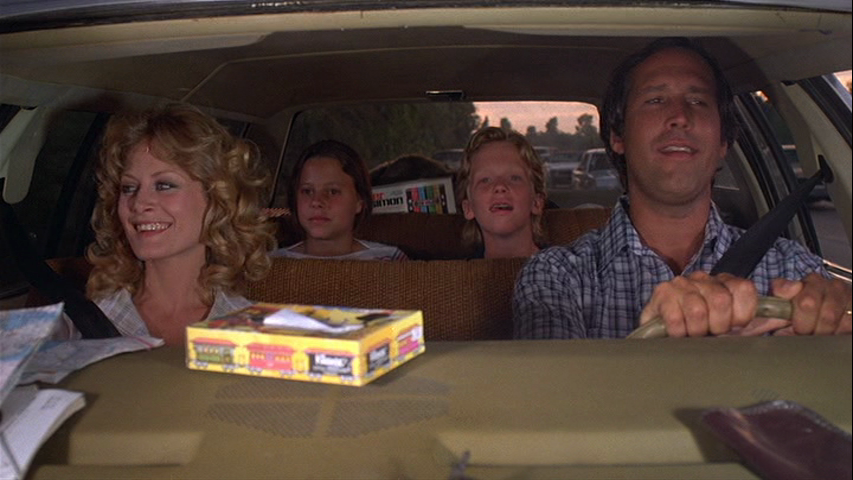

Case in point: patriarch Clark W. Griswold warping an earnest family road trip into a suicidal "quest for fun" across Reagan's America. His vacation-mania at first seems like the kind of common enthusiasm any dad would muster to rally his family into a spirited collective of spend-happy tourists. But healthy consumer avidity quickly gives way to obsession as Clark consistently, even cheerfully, forfeits the collateral needed to continue the trip despite the very real threat of total ruination.

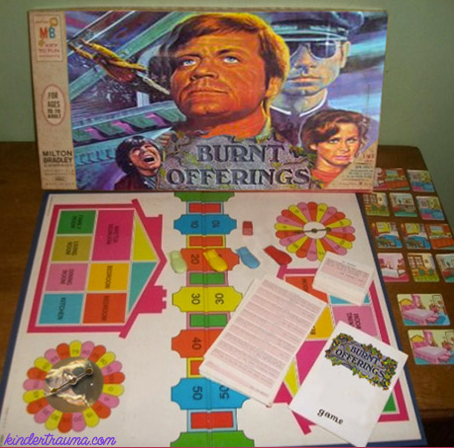

In the first scene of Vacation, he purchases the new set of wheels that will convey his clan on their doomed voyage. Their previous vehicle is instantly demolished by the crooked dealership, the first of several burnt offerings that will eventually include hubcaps, a pair of glasses, a diaphragm, luggage, credit cards, cash, a pet and an elderly relative. The demands of the vacation become higher the closer they get to their goal, but the Griswolds part with them with unnerving light-heartedness.

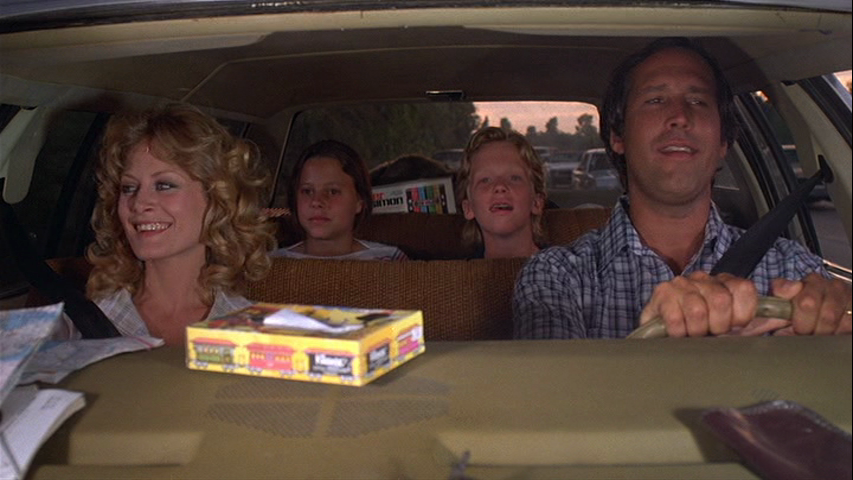

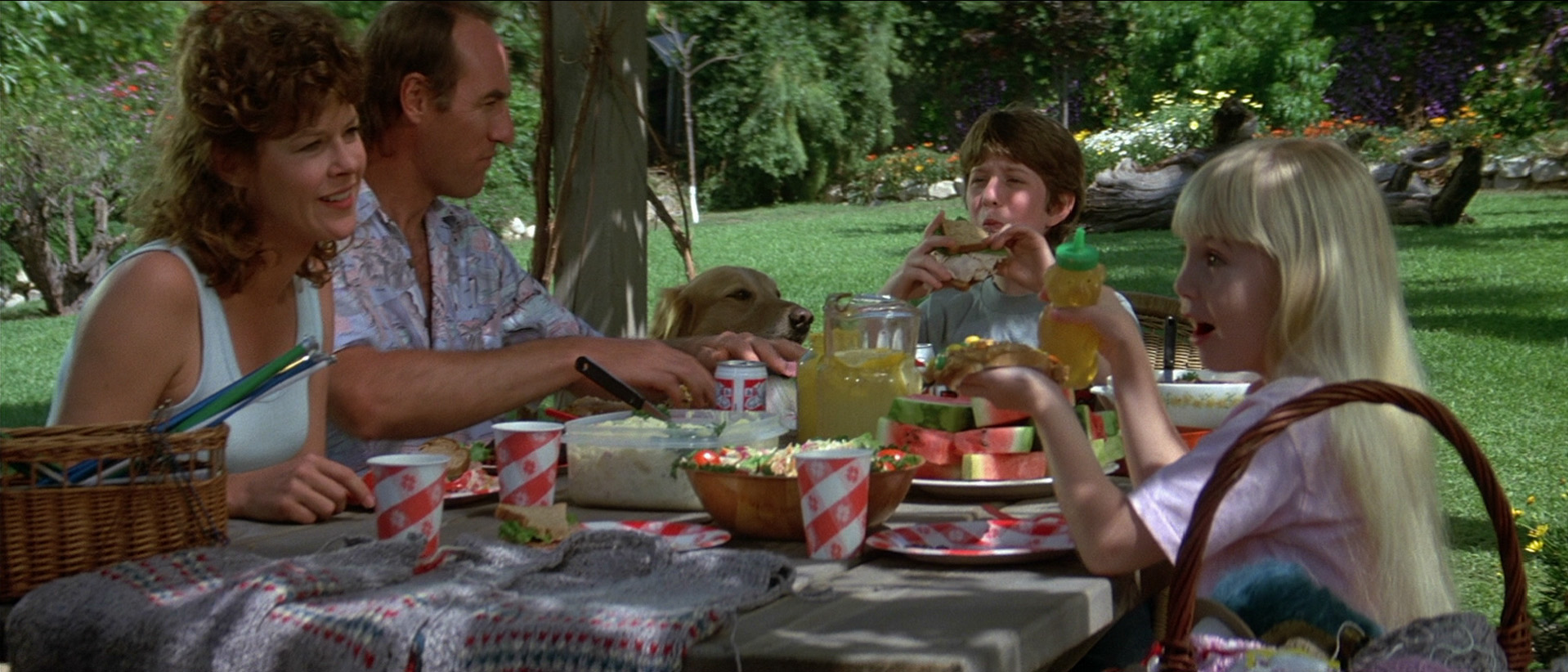

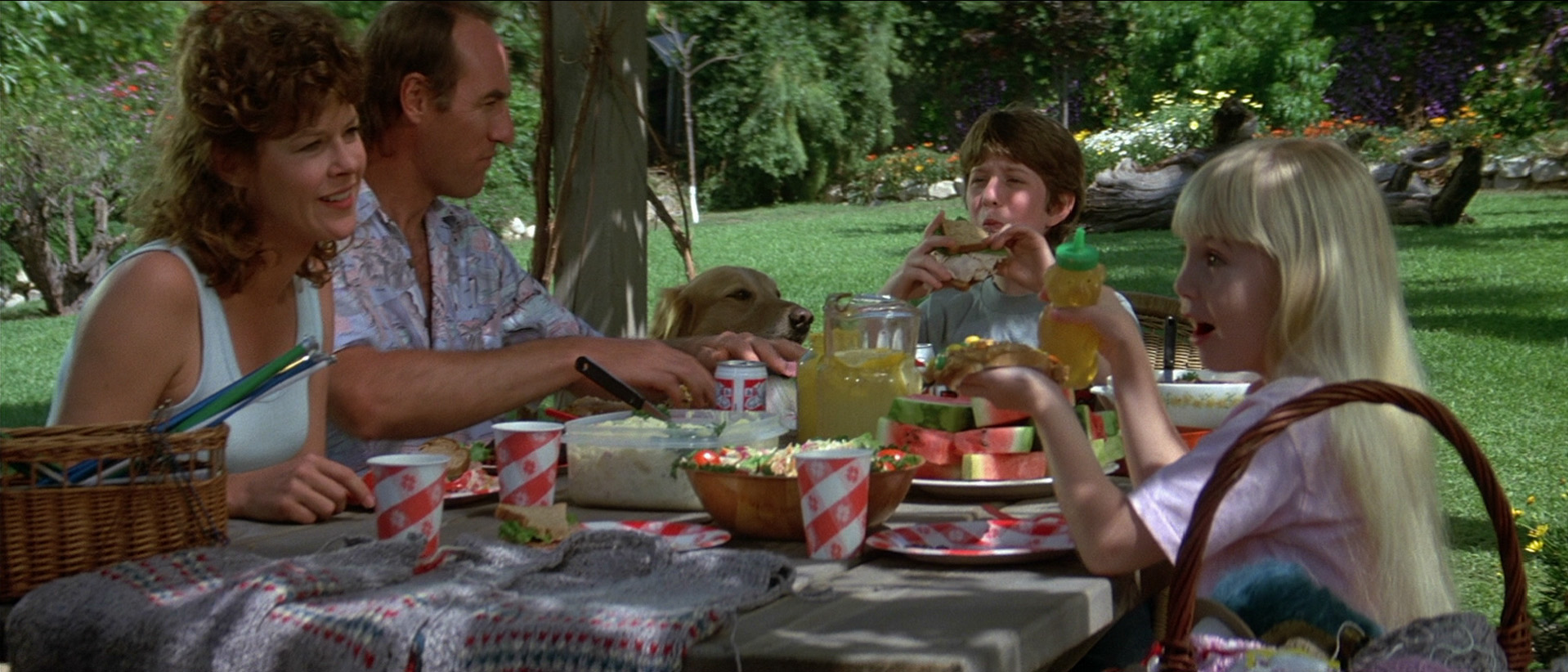

Although the story of Marian Rolf placing herself and her family under the dominion of a carnivorous, life-sucking countryside house features significantly less lampooning than a cross-country trek to Walley World, it inflects similar warnings of excessive recess. Like the Griswolds, the Rolfes are a happy clan who travel to a California destination for a disastrous summer sabbatical that threatens to tear them apart. Granted, the Griswold vacation takes them roughly 2,400 miles farther than the Rolfes, who arrive at their holiday haven fairly early in the film and don't spend much of the movie on the road.

But that small amount of travel is accomplished via a 1974 Ford LTD station wagon, not too different from the modified 1979 Ford LTD Country Squire station wagon* that serves as the Griswold's metallic pea "Wagon Queen Family Truckster".** Burnt Offerings opens with the core family - father Ben, mother Marian, son Davey - on the road driving to the house; they'll repeat this trip later with Ben's ill-fated Aunt Elizabeth, occupying the same driver's side back seat as Vacation's ill-fated Aunt Edna.

Ben senses a portent of doom as he walks to the front door of 17 Shore Rd*** for the first time, mumbling, "Forward into the valley of death rode the six hundred." (The calamity the Griswold's vacation will become is similarly foreshadowed as an all-consuming Pac-Man comes after the Truckster on the Bally Astrocade while Clark attempts to lay out the trip-tic - controlled by son Rusty, suggesting that the family will sabotage itself - but, like Ben, Clark chooses to ignore it). The majestic but rundown neoclassical-revival home is pitched by eccentric siblings Arnold and Roz Allardyce with the brocheure-ready slogan: "Beyond anything you have ever seen in your life!" Roz raves to Marian how it represents "centuries", that it will still exist long after she's gone, that it's "practically immortal," which seems an absurd declaration given the dilapidated state of the house when the Rolfes arrive. But the house has just been waiting, relying on a new family and the energy tapped from their collective holiday jubilation that it can harvest and very literally use to rejuvenate itself.

When the Griswolds finally make it to Walley World, it's empty and seemingly dead, a ghost town of stagnant swing rides and roller coasters. Manic with holiday zeal, Clark pulls a gun and demands the rides be activated, effectively bringing the park back to life. These terminal stations are exactly that: they lure living human beings to them by awakening an urgency for retreat which excites itself into a fervor the institution in turn taps for sustenance, a symbiotic relationship akin to plants that attract parasitic mini-wasps.

Incidentally, "Vacation '58", the short story by John Hughes that inspired his screenplay for Vacation, references the House of Mud that's the butt of a recurring gag in the movie. In the story, the vacationers learn the House of Mud isn't there anymore because it collapsed, killing the curator and his family. Another house that murdered a family!

There is of course no suggestion within the narrative of National Lampoon's Vacation that Walley World is a sentient epicenter of evil that regenerates itself by draining the life force of its occupants. But what are the Disney theme parks if not culturally-approved vampires, relying on hordes of vacationers to keep it running, demanding youth and energy, promising revitalization for its inhabitants while feeding off their income and initiative for the sake of its own prolongevity?

Stripping characters of something vitally human - dignity, civility, sanity - is one of the intrinsic links between comedy and horror films, and the same threat that hangs over the Rolfes pervades the entire National Lampoon series. European Vacation is the same kind of xenophobic displacement horror odyssey as Hostel or Turistas. Clark, driven to the edge of mental stamina by the demands of the holiday, actually wields a chainsaw while dressed as Santa in Christmas Vacation. The thin wall that separates comedy from horror (Mr. Hobbs Takes a Vacation from The Evil Dead) is the reason Clark's chainsaw is applied against the neck of a loose newel post and not those of Griswold family members.

In fact, the Chevy Chase "nightmare vacation" romp was more thoroughly mingled with the horror film 8 years later in Dan Aykroyd's Nothing But Trouble, in which a yuppified version of Clark Griswold sets out on a spontaneous road trip with the same optimistic goals as his National Lampoon counterpart (read: hoping to get into Demi Moore's dress-shorts). He finds himself and his three travel companions trapped at a decrepit house in Valkenvania, New Jersey that's half-Tobe Hooper production design circus,**** half-Dunsmuir House (with two mutants who look like they stepped out of The Hills Have Eyes - yet another disastrous vacation movie with a Midwestern clan on a roadtrip to California with a dog who ends up dead - hanging around for good measure).

Nothing But Trouble connects directly to Vacation's dark undertone by also having Chase ride a roller coaster with an excellent name: "The Whipper Snapper" in Vacation, "Mr. Bonestripper" in NBT. Chase escapes a horrible death on the tracks of the "Bonestripper", narrowly escaping before his skin is flayed and bones tossed into a huge pile of femurs and rib cages contributed by previous travelers, a more literal version of the vitality the Vacation theme park gathers from its visitors.*** **

Aykroyd's movie depends on the classic horror movie structure in which characters are trapped against their will in an unfathomable nightmare from which they must awake and return to normalcy. What makes Burnt Offerings and Vacation such interesting and comparable kind of horror films is that its characters are drawn towards their own potential destruction, and continue on that path even as the peril becomes increasingly apparent. In horror movies, stability is what's threatened: the body (The Fly), the mind (The Tenant), the soul (Invasion of the Body Snatchers), the facility (The Thing), the family unit (The Shining).

In those films, it's an invading force that rocks the foundations of the character's lives, but Offerings/Vacation taps into a different kind of horror: the idea that the hero invites destruction upon the robust balance of his own existence, effectively sacrificing himself and everything he cares about if it means preserving the artificial high stemmed from a perceived sense of purpose. The self-destructors of these two films are Clark Griswold and Marian Rolf, the one person in each family who has nurtured the trip from the beginning and obsessively seen it through to the bitter end.

On the Vacation commentary, director Harold Ramis says that his film is “the story of a dad who basically gets two weeks off a year and overcompensates like a madman to give his family everything he didn't give them for the rest of the year." While that seems like a solid impetus for the project, at some point it became more about a dangerously deluded actual madman who uses his two week vacation to convince himself and his family that he is in control of their fate, when in fact it's becoming steadily wrested from him as he slavishly sticks to his muddled holiday plan.

Somehow, he manages to delude himself into believing that every disaster that befalls the family was of his design: he's impressed with himself, for example, when the Wagon Queen flies off the desert read and jumps 50 yards, as if he performed the stunt on purpose. He meets each holiday hardship with deranged elation, under the impression that he’s being challenged by a single malignant force with the sole purpose of spoiling his carefully prepared agenda. The same can be said of Marian, who giddily claims credit for cleaning up the Allardyce House even though it's regenerating on its own while she sits upstairs listening to old records. The house has set a role for her which she carries out instinctively, believing herself pivotal to the success of the vacation when in fact she's a mere tool towards reaching its ultimate goal.

She's not doing any actual work, for what is work but the antithesis of "vacation"? Ben, like fellow writer Jack Torrance, finds he can't work while at his respective retreat. Despite the ideal setting, personal industrious drive seems to be sapped from the vacation victims in order to lull them into a state of indolence: all the better to further their reliance on the trip's seductive tranquility so that they eventually yield all power to it. The term "sabbatical" derives from the Hebrew concept shmita, or sabbath year, when the land would be left to lie fallow and all agricultural activity was forbidden, the result being a bountiful harvest. This alleviation of effort represents a faith in God: step back and let Him do the work, and the land will cultivate itself.

It strikes me that the Rolfes' summer vacation isn't dissimilar to Sergeant Howie's trip to Summerisle in The Wicker Man: like him, the family is tricked by a group of weirdos into becoming unwitting sacrifices towards the replenishing of the local's home. The Rolfes are put in a position where they're not expected to do anything strenuous (like Sgt. Howie, whose policework on Summerisle is a complete facade) and are really only required to die. It's like the Neil Young song "You Never Call" in which he describes death as "the ultimate vacation," while all the living "work work work", again suggesting these institutions need to take something from their occupants, and that the ultimate ambition of the "vacation" is sacrifice. (Even in comedies the vacation demands a sacrifice: think of the Ferrari in Ferris Bueller's Day Off.)

For his part, Clark leaves behind a job developing newer and better food additives to confront the holiday road with the conviction that "nothing worthwhile is easy." Clark approaches the trip like a job, taking a leadership role, plotting out all the logistics, offering solutions and reassurances to his underlings. It would be truly unnerving how naturally he responds to the most appalling developments, if he wasn't so persistent on taking action against the pitfalls of the journey. Clark can't simply turn off and hand over control. (This aversion to idleness may explain why Clark is constantly, albeit inadvertently, trying to murder Eric IDLE in Vacation's like-minded sequel, European Vacation.)

However, Clark's insistence on "working" on making their trip a perfect vacation over abdicating in favor of a calm holiday mindset is at direct odds with his monomaniacal fixation on Walley World. His obsession aligns perfectly with the demand of the vacation so that, however desperately he might paddle, Clark is always trapped in the vacation stream and has no real control over it. Hence, the rewards of the everyday job he's escaping have to be squandered on his time away from it.

Clark seems resolved that a man is more than his job, determined throughout the National Lampoon movies to prove that his actions away from work define him as a person and are meaningful, even if they're negative actions that make him look like a monster (taking people hostage, betraying his wife with women in swimming pools both real and imaginary, vandalizing ancient milestones and national monuments, etc). His image of himself in "vacation mode" is depicted perfectly on the famous Boris Vallejo poster. The image of Clark as a hyper-represented, Herculean he-man with scantily-clad versions of the female characters embracing each of his bulging thighs is a perfect rendering of how he perceives himself while on his mighty quest.*** ***

But this delusion of dominance just makes him dangerous, fueling a tenacity against admitting defeat that makes his family afraid of him. He further puts them at risk with his insistence on activating the Walley World attractions - he has no idea why the park has been closed down, what maintence is being done on what ride, whether the roller coaster will literally fly off the tracks and take out his entire clan. He ignores Marty Moose's warning entirely, even though the mascot is the paganistic symbol that's driven him throughout his journey, promising Clark that "E is for Everything you want to be." (Jungian analyst Sherry L. Salman equates the male psyche's 'Horned God' - an archetypal protector and mediator of the outside world to the objective psyche - as compensation for inadequate fathering.) Clark believes the moose owes his family, for all the time they've dedicated to watching his show and traveling to his theme park, not willing to recognize that his own need to create a never-ending vacation was doomed to failure by the simple truth that all vacations must end.

Marian is more the Clark of her family than her husband, the one obsessed with the vacation not ending. Like Clark, she embodies the sad reality that there's often only one member of a family who actually enjoys an extended vacation, or at least one to whose benefit the trip caters more than the others, who either can't or won't acknowledge the misery of everyone else involved. Clark admits to never having fun as a kid on his family's vacations, but is determined to have fun now (seemingly ignorant that Rusty is now in his position). Marian appears dissatisfied too, although as the plot of Burnt Offerings develops her desperation is revealed to be deeper and more dangerously insatiable.

Although it's largely unspoken (a long early scene of the family in their small apartment was cut for the sake of pacing), the couple in Burnt Offerings are clearly tempted to occupy a huge, beautiful house because of their lower social standing. Same reason people go on cruises, or buy a time-share in Baja. They haven't earned the privilege, they can't and probably won't ever be able to afford anything like the Allardyce house, so of course they emerge themselves in a fantasy that's going to be tough to abandon.

As other members of the family grow steadily despondent with holiday fatigue and depression, Marian maintains her cheery temperament in spite of all the horrible and unnatural events: Ben's near-drowing of Davey, Aunt Elizabeth's death, the house literally shedding its exterior walls and growing new "skin." She's like the vacationing patrons of Delos in Westworld, who grow too comfortable in the illusion of lawless hedonism within the confines of the theme park that eventually turns real, or Douglas Quaid in Total Recall, who might be confusing his simulated vacation with his actual life.

In the end, Marian can't stand to be parted from the fantasy and mistakes the vacation home for where she truly belongs. Ultimately vacation is all she ever wanted: she doesn't just stay, she becomes a part of the house's history, moving into the attic and taking over the role of Mrs. Allardyce. This final twist was a change by director Dan Curtis from the more ambiguous climax of Robert Marasco's book, which is interesting when you consider that Stanley Kubrick made the same change to the fate of Jack Torrance in his version of The Shining (Stephen King has listed Marasco's novel as an inspiration for his own). Curtis and Kubrick's film ends with the ultimate idleness: just as Jack is now frozen in the 1921 portrait of the Overlook staff, the final shot of Burnt Offerings has reduced the obliterated family members to individual portraits set side by side, while Marian has taken the place of the incapacitated old lady confined to the attic, "sleeping all the time."

Marian hasn't actively taken part in the family vacation - she doesn't swim with Davey, she refuses to make love with her husband, she focuses on housework and even shrugs off the very sad and sudden death of Aunt Elizabeth - while at the same time cherishing it more than anyone else. Mentally, she's already progressed the events of the summer (and the essence of those involved) to what all vacations become: images, photographs, "memories of a lifetime" as she whispers to herself, gliding over Mrs. Allardyce's picture collection sentimentally. Her method of serving the vacation is the exact opposite of Clark's: rather than be assertive and foist herself on her family, she successfully estranges herself from them.

In bringing back to life an ancient estate she has self-immolated, trading her own identity for that of a bitter old woman alone with the pictures of a vacation that never really happened. Clark, on the other hand, never loses touch of his dream for a perfect holiday. Even when he's ripped off a hotel cash register, he still stops to admire the Grand Canyon for a total of 5 seconds before piling the kids into the car and peeling off. When the rest of the family complains, he absorbs it into his immutable optimism. In the end, Clark's aggressive bonding may be the reason the last shot of Vacation, while also a family portrait, is one of them all together instead of separated in different frames.

Either way, not everybody makes it out alive. In both films, the vehicle - a station wagon, that wood-paneled chariot of the 20th century American family - becomes a meat wagon. The mode of liberation is converted into a trap and a casket, quite literally in the case of Ben Rolf. The Griswolds end up transporting the body of Aunt Edna (Imogene Coca), who passes away unnoticed somewhere near Flagstaff, to its final resting place.

Edna has been the most outwardly critical of the trip, castigating Clark for his incompetence in successfully spearheading the Walley World expedition. Her unexpected enlisting of the family to take her to Phoenix, waylaying the Walley World goal by many hundred miles, threatens the vacation and therefore makes her an ideal candidate for sacrificial holiday lamb. The very concept of a vacation is based on youth and vitality - outdoor activities, life-shaping experiences, rides and roller coasters and endurance for long travel. Anyone who can't keep up simply won't survive; as the kids learn "don't die unless somebody's at home" - on vacation, nobody's home!

That's true even in Burnt Offerings: the Rolfes think there's an old lady in the attic, but in truth nobody is at home. Bad news for poor Aunt Elizabeth (Bette Davis), who first appears a spry 74-old-year with aspirations of obtaining a driver's license. In many ways she's the complete opposite of grouchy old bully Edna,* providing encouragement and obvious love for nephew Ben and his family, especially spunky son Davey. But while Elizabeth ostensibly supports the Rolf family vacation she doesn't take part in it, sitting off to the side while the boys swim and being generally ineffectual in the replenishing of the house (which for its part immediately rejects her presence, making the overhead light of a pantry full of life-sustaining goodies unavailable to her but freely offered to young Davey).

So the vacation claims her too, sucking the life from her frail body until she's spirited away by a grinning spectral Chauffeur with a giant coffin from the back of his Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost Hearse. The fate of the rest of the family is sealed when Marian is driving Ben and Davey back to the house in the station wagon after Ben's abortive escape, and Ben turns to see that her face has been replaced by that of the Chauffeur.

Vacation has its own version of Offering's smirking Chauffeur, a spectral interloper who visits ruin upon the transiting set. You might think it's James Keach's cop, another imposing figure with sunglasses the hero meets on the road, but actually it's Christie Brinkley's similarly unnamed Ferrari Girl. While less obvious in a non-horror movie, F.G. makes for an almost phantasmal presence throughout Vacation. No one in the film except Clark has a direct interaction with her.

Ellen and the kids ultimately see her, but then Aunt Elizabeth sees the Chauffeur just before her death. Neither speak throughout their respective film (although Ferrari Girl does in her last scenes alone with Clark). The husband is really the only one to witness his cruising demon, both of whom are directly connected to their cars, which we've already established serve as harbingers of death. (It's notable that the Brinkley surrogate in the recent Vacation rebootquel suffers a horrific James Dean-style demise, hitting a truck head-on, which nobody sees happen.)

The Chauffeur first appears to Ben in a dream following his attempted drowning of Davey,** the first indication that something is seriously wrong within the family unit. Likewise, Clark initially spies Ferrari Girl when his family is at their most intolerable, the kids being obnoxious with Ellen screaming at them, then henpecking Clark for speeding. Clark imagines himself in the car with Ferrari Girl (over the shoulder of his wife), just as Ben imagines his wife has transformed into the Chauffeur.

Even though the hearse (called a "limousine") and its spooky driver show up in Marasco's novel, Dan Curtis added the detail of the Chauffeur's sinister grin, based on a scarring memory from his mother's funeral (it's a neighbor's funeral in the book) where he witnessed a chauffeur laughing outside of the parlor (so like John Hughes, Curtis harked back to a childhood trauma in the telling of his vacation nightmare). Like taking a relaxing vacation, enlisting the services of a chauffeur is typically equated with leisure, luxury, taking things easy; in Burnt Offerings, the Yokai jockey in the Kato jacket leisurely ushers Aunt Elizabeth to her doom, an agent of fatal idleness.

Ferrari Girl nearly succeeds in destroying the family, both literally (almost causing Clark to crash and kill everyone in the car) and figuratively (coming between Clark and Ellen's marriage). It's clear that her youth threatens the Griswold clan, not least of all Aunt Edna, for whose unmistakable oldness Clark has only contempt. Edna's dependency and cantankerousness are the exact opposite of F.G.'s vitality, freedom and impulsiveness. Brinkley's an upturned-collar manifestation of the vacation itself, a sun-tanned avatar for Clark's obsession and how he creepily sexualizes the vacation high.

I never understood why Clark was such a rapacious horndog when he's got an incredibly sexy (and sexually energized) wife, but the answer is right there: his pursuit of Ferrari Girl's appetizing, yummy love for sale*** has less to do with libido than his fervor. It's never established how Brinkley's homewrecker continuously crosses paths with the Griswolds, unless you accept that she's just as supernatural a figure as the Chauffeur, whose goal - to destroy the family - is fundamentally the same. Despite her sunny disposition, Ferrari Girl's threat to the family puts her firmly in the tradition of deadly, anonymous motorists like the trucker in Duel and the unseen driver of the Cadillac Funeral Coach in Dead End (as perfect a mash-up of Burnt Offerings and Vacation as we're ever likely to see).

Marian has her own apparition only she can see: the alleged Mrs. Allardyce cooling her heels up in the attic, serving as a convenient excuse to not abandon the vacation. Ironically, Ben frets that the old lady in the attic might die while they're in the house, unaware that they're the ones dying to give her new life, which she'll steal from caregiver Marian. Karen Black may have been inclined to care for an elderly recluse, having been saddled just the year before with caring for her alcoholic father as an unhappy aspiring actress in The Day of the Locust.

The father, it must be noted, was played by Burgess Merdith, Burnt Offerings' Arnold Allardyce himself, the man who tricks the Rolfes into renting the house in a plot that will effectively turn Black's character into his mother. Meredith turned up the following year in The Sentinel as Charles Chazen, another alliteratively-labeled eccentric old weirdo living in an old building and aligned with the forces of darkness conspiring to destroy the new resident. Sentinel, directed by frequent Oliver Reed collaborator Michael Winner, featured an early appearance by Beverly D'Angelo, six years before she hopped in the Wagon Queen as Ellen Griswold.

Although The Day of the Locust and The Sentinel aren't technically vacation horror movies (they would technically be "new tenant" horror movies along the lines of Rosemary's Baby), they share more with Burnt Offerings than just cast members. For one thing, the end game in all three movies is to destroy the main characters. The setting of Locust, the dilapidated, soul-sucking San Bernardino Arms, is as rundown as the Allardyce home. Black/Meredith's last name in Locust is Greener; in Burnt Offerings the garden becomes greener, life returning to the house as the energy of residents is suctioned from them.

The intimidating Brooklyn brownstone of The Sentinel, revealed as a gateway to hell, seems constructed to torment Alison Parker, the young woman who moves in only to find herself trapped and ultimately forced to remain for the rest of her life on the top floor in a rocking chair. Like Marian in Burnt Offerings, she's become a living corpse staring vacantly out the top floor window like grandma in Texas Chain Saw Massacre or Mrs. Bates in Psycho.**** In Locust, Meredith suffers an agonizing, drawn-out death similiar to the fate of Aunt Elizabeth, while Black's refusal of William Atherton's sexual advances*** ** and the near-rape that results from it has a very similar vibe to her turning down a heaving Ollie Reed in their scene from Offerings.

That scene is one of the movie's most effective, since the viewer can empathize with Ben's need to reconnect with the wife who's slowly being pulled away from him while feeling deeply uncomfortable with his aggressive seduction at the same time. We've already seen Ben, possessed by the spirit of the house, try and murder his son in the pool so the fact that his failed enticement of Marian occurs in the same pool (at night, no less) makes you worry what he'll do after she rejects his advances.

Vacation also features a seduction in a swimming pool at night that drives a wedge between the married couple. Clark has been amorous throughout the film, trying to get Ellen to have sex with him at almost every rest stop no matter how inconvenient the location/circumstance, only to be impeded by intruding kids or a horny dog: the vacation won't allow him to copulate. Not until it sends in its emissary - the Ferrari Girl - not to actually give Clark what he wants but to expose his attempted philandering and demolish the family unity.

The ploy backfires because Ellen somewhat uncharacteristically plays into Clark's holiday mania by forgiving his transgression, stripping nude and diving into the pool herself. That she responds to the cold water the same way as Clark suggests Ellen is just as willing to jump into a situation for the sake of fun without fear of consequence as her husband - it brings them together. Ellen doesn't mind exhibiting her tryst in front of the entire hotel, whereas the idea that Ms. Allardyce may be watching from her window in the attic is enough to cause Marian to turn down Ben's offer of an impulsive dalliance.

Taking his cue from Clark & Ellen, Ben's proposal of a late night lark is very much in the vacation mood. But since Marian is only interested in looking back at the vacation and not actually participating in it, Ben's bid to assimilate himself into her holiday agenda fails. Ben is looking to the future: he wants to initiate the act of procreation, maybe get the ball rolling on his and Marian's very own Audrey, but Marian can only experience the events as if they happened long ago in the far past.

As we'll discover, that's really her up in the attic looking down at the frolicking couple; in the present, she's preoccupied by her ultimate fate, becoming an old woman living on her own, her loving family all dead and buried. For the Griswolds, the night swim reignites their relationship, setting things up for the vacation to end on an unlikely positive note like Preston Sturges' The Palm Beach Story, and not an unexpectedly horrible one like Catherine Breillat's Fat Girl. For Ben and Marian, it's the Fat Girl-train to post-holiday tragedy.

At the center of both films are family men with two clear goals: to get it on with his wife and to form a strong bond with his son,*** ***even at the kid's peril. Ben splashing around with Davey in the pool quickly goes from mild roughhousing to full-blown murder attempt. Although he's obviously been possessed by the cancerous spirit of the house, it starts with a hint of resentment after Davey undermines his father by figuring out how to work the pool cleaner. Clark lets Rusty inhale a beer, certainly not healthy (although because of Ben's misadventure in the pool, he has to enjoy his own beer alone). And whether it's a reflection of his poor protector skills or a hint of future homicidal intent against his own, Clark's canicide**** *** is unnerving. He hates the dog - leaving him tethered to the bumper is an act at least subliminably equatable to Ben's attempt to kill the sensitive and somewhat annoying Davey.

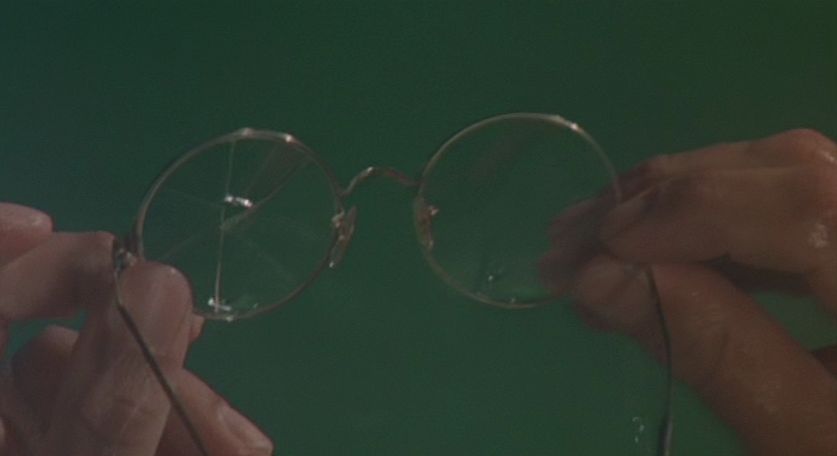

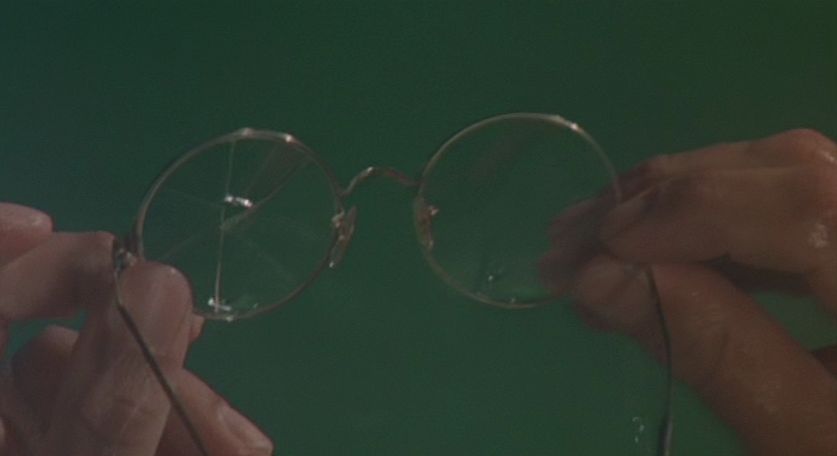

Oliver Reed and Chevy Chase,* card-carrying members of the Three Musketeers and the Three Amigos, may not look alike but they dress the same, both sporting tan Members Only jackets. They each have a nickname: Clark's wife playfully calls him "Sparky" while Elizabeth refers to her full-grown nephew as "Benji." Both men wear glasses, although apparently don't need them all the time. In particular, Oliver Reed seems to be suffering from glasses continuity in the first scene of the movie: they constantly disappear from his face from one shot to the next.

I don't blame script supervisor Alan Greedy (although he is one selfish bastard), since this is clearly a foreshadowing of the broken pair of glasses Ben finds in the pool, which in turn foreshadow his death through the windshield of the station wagon, that persistent carriage of death. Clark also breaks his glasses in yet another station wagon incident, when he sends the vehicle soaring off a dune in the middle of the desert.**

What is it about their vacation apparel that empowers these men? Ben puts on the glasses and tries to kill his son; Clark puts on the shoes given to him by Eddie that empower him to go after Ferrari Girl. Put 'em together and you've got the classic Charles Beaumont Twilight Zone episode "Dead Man's Shoes." Or better yet, maybe Burnt Offering's damaged specs are a hark back to an iconic scene featuring broken glasses from the classic 'Zone episode "Time Enough at Last" starring Burgess Meredith. And how about this: National Lampoon's Vacation came out the summer of 1983, same as Twilight Zone: The Movie, in which Albert Brooks recounts the plot of "Time Enough at Last" to Dan Aykroyd, Chevy Chase's co-star in Spies Like Us and Nothing But Trouble. The movie was narrated by Burgess Meredith.

His Arnold Allardyce appears at the beginning to offer damnation, whereas Eddie Bracken's Roy Walley appears at the end of Vacation to offer redemption. They have a real god/devil thing going when you place them next to each other,*** especially when you consider that Arnold is the most charming conspirator against the vacationing group in either movie (and like Eugene Levy's shyster car salesman, he's on wheels). The intervention of soft-hearted Roy Walley is the miracle that sees Clark & co. escape their nightmare vacation without going to jail or ending up dead like Aunt Edna, shot to death by police.

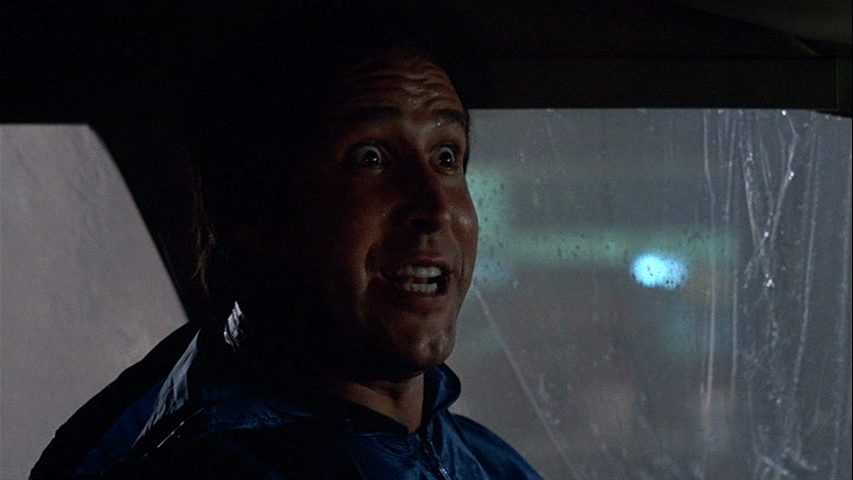

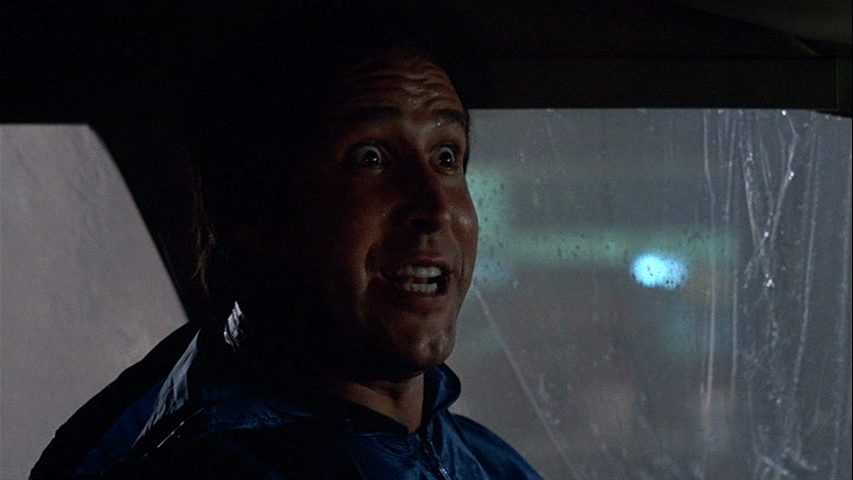

The death of each movie's respective elderly lady almost brings an end to the vacation,**** leading Ben and Clark to impressive freak-outs during a rainstorm, although for different reasons. Seeing the house regenerate itself in the wake of Elizabeth's demise, Ben renounces the vacation, scoops up Davey and tries to drive away from the house, crashing the car when a tree lands in their path. Undaunted, he backs up the station wagon and tries to run through the fallen oak, bringing the car to near-destruction (but not quite, just like Clark's Truckster) as Davey shouts at him to stop from the passenger seat. Clark's clan also fail to calm him out of his hysterical tirade, brought on by the idea that they have to cancel the trip based on all that's gone wrong, most recently the end of Aunt Edna.

His frozen-grin rage reaches its apex here: Clark has basically become Jack Torrance, except that his homicidal cabin fever comes from being in the car too long. He's already pulled a Norman Bates sneaking up on Ellen in the shower, and his manic enthusiasm could easily be put side-to-side with Stepfather Jerry Blake's psychotic sprightly demeanor*** ** in a YouTube video (if it hasn't already). Meanwhile, Ben works himself into a catatonic state doing the exact opposite, trying to escape his family's rapidly ruinous sojourn.

So one father is desperate to end a vacation, the other maniacally insists it continue at all costs. Ben's attempt to flee the house is abrupt and violent; eventually, Clark will rashly resort to violence by purchasing a (phony) gun and taking security guard Russ Lasky hostage so that his family can enjoy the vacation he had planned. Clark also flees from a giant house/hotel, after robbing the till of the (supposedly haunted) El Tovar Hotel at Grand Canyon National Monument.

This scene, where the continuation of the vacation is threatened when the desk clerk refuses to accept a check from Clark for much-needed cash, reminds me of the part in Ray Milland's low-budget apocalyptic drama Panic in Year Zero! where the hardware store owner refuses to take a check and Milland is forced to rob him. Milland's family (wife, son and daughter) are on a camping trip in that movie when the bombs start to drop and are subsequently compelled to escape to their cabin, a vacation based on survival.*** ***

Finally, I have to mention the indirect director cameos of each film. Harold Ramis appears in Vacation as a voice only, that of Marty Moose instructing the Griswolds that their vacation has been canceled. Dan Curtis appears in Burnt Offerings as an image only, one of the many portraits spread out on Mrs. Allardyce's table. Notably, they are both part of Clark and Marian's respective obsessions: Ramis the horned mascot into whom Clark has poured his faith, Curtis a face in the collective of memories to which Marian adds her own family. Clark strikes out at his tormentor, but Marian goes back into the house to her beloved pictures, unwilling to let go of the fantasy that she's held onto since entering the Allardyce household.

The vacation becomes an inversion of its purpose: instead of escaping, Marian becomes trapped. It's no longer a temporary trip but a permanent situation. Vacation ends on a much more optimistic note with the family heading back home, but like the Rolfes they are forever frozen in still images. On the film's soundtrack, Lindsey Buckingham sings: "Some will go/Others just stay and stay." Maybe he's not crooning about staying at home - maybe he means staying on vacation, indefinitely. Maybe next time, they should just stay home and play a board game.

~ OCTOBER 18, 2016 ~

* The doomed family in The Hitcher (something like a combination of the Griswolds and the Rolfes) drive a 1974 Ford LTD Country Squire.

** I'm absolutely convinced the Wagon Queen is possessed a'la Christine, keeping the family alive so the vacation may continue, most notably by driving them safely to the motel after Clark has fallen asleep behind the wheel. Also by consistently deploying the cheap airbag (albeit belatedly). Cue the Chevy Chase right-handed steering wheel on the Rolls Royce joke from Caddyshack ("Put that steering wheel over here where it belongs!")

*** AKA Dunsmuir House in Oakland (notably changed from the book's East Coast setting), which also stood in for Morningside in Phantasm. Apparently the place screams cinematic murder: it's where Mike Myers spends his dread-soaked honeymoon in So I Married an Axe Murderer. In that movie, Anthony LaPaglia is driven to the house by Charles Grodin, who was in Seems Like Old Times and The Couch Trip with Chevy Chase, and had previously been an inadvertent conspirator with all them witches in Rosemary's Baby, not unlike the Allardyces in Offerings.

**** Burnt Offerings has an interesting Tobe Hooper connection: during the shooting of the film, Karen Black was pregnant with son Hunter Carson, who would later star alongside his mother in Hooper's remake of Invaders from Mars. His father is L.M. Kit Carson, writer of the screenplay for The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2.

***** Chase's hapless WASP always seems to have trouble relating to black people, whether "Honky Lips" Griswold's embarrassing use of slang gets his hubcaps hijacked in St. Louis or Chris Thorne's pathetic appeals fail to convince the members of Digital Underground as to the evil of Akyroyd's ancient judge, Akyroyd finding himself down with Digital after some surprising successful freestylin on the organ. (Chase's character in Nothing But Trouble is named Thorne? Like in The Omen? Tell me Aykroyd wasn't very consciously making a horror movie.)

****** Has anyone ever noticed what's going on behind Chevy Chase's muscular legs on the Vallejo poster? A dog - presumably Aunt Edna's dog Dinky - is growling at a snake that's poised to strike. What's that all about?

* Combine them and you've got the obnoxious aunt in Damien: Omen II (also named Marion), who dies unnoticed like Edna, by supernatural means via conspiracy that includes the nephew's wife like Elizabeth, succumbing to a coronary induced by an evil raven. The baneful power that controls the twisted fate of characters in the Omen movies isn't unlike the compelling force that draws the Rolfes and the Griswolds. (Also dogs, so prominent in the first movie, are notably absent in this sequel. Omen II was helmed by Don Taylor, who directed Burnt Offering's Oliver Reed in The Great Scout & Cathouse Thursday.)

And while we're listing Jerry Goldsmith-scored horror sequels with elderly family member mid-movie casualties, I'll just mention Grandma Jess from Poltergeist II, who was not an aunt but (as her name suggests) a grandmother. The Freelings were another station wagon-driving family of that era of horror film, and like the cars driven by the Griswolds and the Rolfes, Steve Freeling's is systematically destroyed over the course of Poltergeist II. Which is sort of a vacation movie. The Freelings are away from their own home - which imploded at the end of the first film - and stay at somebody else's house, Steve's out of work, the kids are home from school (except Dana, whose absence is completely ignored). Even after Grandma Jess dies and her house technically becomes theirs I guess, they still set out for a traumatic little trip to the Other Side.

Geradline "Grandma Jess" Fitzgerald was also Dudley Moore's grandmother in Arthur and its sequel Arthur 2: On the Rocks, which is similar to Poltergeist II: The Other Side in having its heroes be broke, displaced and despondent and both being directed by filmmakers who would wed actresses from their own movies (Cynthia Sikes from Arthur 2 and Lynn Whitfield from The Josephine Baker Story, respectively).

** Oliver Reed ended up reincarnated as a surly, murderous chauffeur who menaces a child in 1981's Venom.

*** Now that the comparison between Ferrari Girl and the evil forces of Burnt Offerings has been made, it's impossible for me not to watch creepy Burgess Meredith leering at Davey from the window and not hear June Porter singing "Little Boy Sweet" over the scene.

**** Richard Harland Smith, writing for tcm.com, notes that Curtis' alternate ending to the original novel is a reworking of the end of Psycho, with the protagonist going up to the attic instead of down to the cellar searching for a character named Marian. Psycho is another sort of "vacation gone wrong" movie, in which the traveler's life violently ends just after she decides to end her trip and return home. Note also the Psycho parody in the hotel bathroom in Vacation.

***** Another LocustDay of the Locust/Sentinel connection: the boyfriends are played by William Atherton and Chris Sarandon, both famous for playing two of the biggest douchebags in popular 1980's movies. (I'm thinking of Ghostbusters and Princess Bride, although for Atherton you could of course include Real Genius and Die Hard.)

I'll also take this opportunity to note that, in the 70's, Karen Black brought a fantastic desperation to her characters' guarded desires for love and acceptance. Whether as Myrtle Wilson, desperate not to wither away in the "valley of ashes" in The Great Gatsby, or Miriam Oliver taking on the persona of a dead woman in 1977's The Strange Possession of Mrs. Oliver (funny, since she was Mrs. Oliver Reed in Burnt Offerings), she was a great victim whose very instinct seemed to steer her towards her grim fate. She was a natural casting choice for Burnt Offerings based on her various roles in Trilogy of Terror, directed by Curtis and co-written by Offerings adapter William F. Nolan: a victimized woman revealed to be a succubus, an unhinged individual with multiple personality disorder whose "evil" self ends up destroying her, a burdened daughter ultimately possessed by the murderous Zuni fetish doll she's struggled to survive against who will now kill her own mother.

*** *** Clark also has daughter Audrey, but he clearly has no interest in bonding with her. When he's having a man-to-man moment with Rusty in the desert, he can't even remember her name. Audrey has no proxy in Burnt Offerings, but it's noteworthy that Dana Barron played the od'd daughter of Paul Kersey's girlfriend in Death Wish 4: The Crackdown (no doubt the pot provided her by Jenna Maroney in Vacation served as a gateway to this sad end). It's her death that Kersey is avenging when he throws a man out of a high window onto the hood of his own car. Weirdly, even though he falls from a much greater height and lands in the same head-first position as Ben Rolf, the creep doesn't break the windshield. That's one solidly-built automobile (or a very soft head).

**** *** Friend of The Pink Smoke Kevin Maher points out that Chevy Chase was previously involved with dogs who are humorously killed in Under the Rainbow (which predated all the hilarious dog killing in A Fish Called Wanda). Chase was himself killed and reincarnated as a pup in in Oh! Heavenly Dog. That dog was played by Benji - Aunt Elizabeth's pet name for Ben in Burnt Offerings.

Furthermore, like Under the Rainbow, The Day of the Locust is set in 1930's Hollywood. Both movies feature an awkward character named Homer who services the whims of the female lead, and they both co-star Billy Barty. In Locust, the diminutive character actor throws a rooster to its death (in a cockfight) and in Rainbow, he threatens a dog.

Meredith was also in Foul Play with Chevy Chase, which like Burnt Offerings features an evil chauffeur. And again, Billy Barty!

* Since it's arguably his most popular film role, it's easy to forget what an anomaly Clark Griswold is in the Chevy Chase character bank. Determined, unfettered and achingly earnest, Clark is a complete opposite from the detached rascalism of Ty Webb, Nicholas Gardenia and Irwin Fletcher (and, one assumes, his character from the Paul Simon music video). With Clark, there's no trace of the slacker wisdom that got him out of scrapes with Russian agents, towering Albinos and Nazi midgets - instead he emits bitterness and desperation, and finds himself constantly shafted by grifters who put forth little effort. Some insane part of Clark rejects cynicism in favor of high ideals, ones that would resurface a few years later when Chase played Andy Farmer in Funny Farm, which really should have been called National Lampoon's Rural Vacation.

** Did you know that Sergio Leone made Burnt Offerings possible? Leone convinced Dan Curtis to sell him the rights to the novel The Hoods (which became Once Upon a Time in America), causing Curtis to move on to an adaptation of Robert Marasco's Burnt Offerings. And of course, Leone shot a memorable scene from Once Upon a Time in the West in Monument Valley, where Clark strands the family and nearly dies finding a gas station.

*** Eddie Bracken took over for Burgess Meredith in the lead role of John Patrick's 1953 Pulitzer Prize and Tony Award-winning Broadway play The Teahouse of the August Moon. Marlon Brando ended up with the part in the 1956 movie version. It is crazy to think of those three actors playing the same character.

**** Another (real-life) tragic death while on vacation? National Lampoon co-founder Douglas Kenney, who in the fading days of the summer of 1980 fell off a cliff in Kauai, Hawaii at age 33. He had been suffering from drug abuse and mental health issues, so his friend Chevy Chase took him on the trip to help him get better. Once left alone, Kenney soon went missing for days until his body was discovered. Vacation director Harold Ramis quipped that Kenney "probably fell while he was looking for a place to jump."

*** **Likening Clark Griswold's family-centric mania to that of Jerry Blake might explain why there's a different Rusty and Audrey in every Vacation movie: maybe he's a madman who's kidnapping these kids and forcing them to act like members of his family. When he's done with them or they disappoint him somehow, he dispatches them and picks up two new runaways or orphans. And Ellen just kind of sits back and lets this happen - not too much of a stretch, considering she just sort of shrugs when it appears that her husband has purchased a gun and is holding people hostage at an amusement park.

*** *** The hoodlums who terrorize survivors in Year Zero! at their holiday homes/nuclear retreats put me (as well as Village Voice writer Michael Atkinson) in the mind of the opening of Michael Haneke's Time of the Wolf. Funny Games is also a vacation movie: the family is at their holiday lakeside home when the two uninvited guests come knocking. And like National Lampoon's Vacation, the dog is killed. A dog is also killed in Rear Window, in which Jimmy Stewart is sort of on vacation, stuck in a high apartment looking down like the mysterious Mrs. Allardyce and the priest from The Sentinel. Or just a big ol' creep.