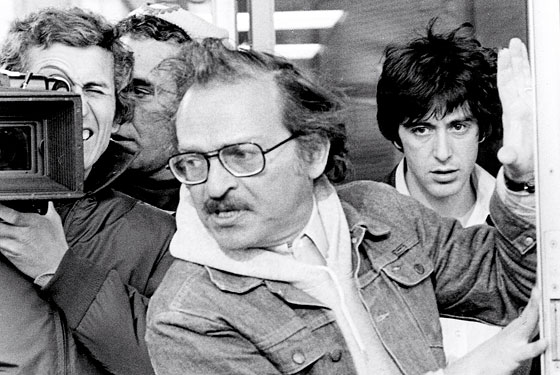

SIDNEY LUMET, 1924-2011

To mark the passing of a giant of American film, I just wanted to re-publish this brief article I wrote for the Journal News in 2009. It was written to promote the Jacob Burns Film Center's Lumet retrospective; unfortunately Mr. Lumet wasn't able to make an appearance so I never got to see him in person. His prolific career may not have been the most consistent, but it began with a masterpiece and ended with another one with lots of great stuff inbetween. I'll miss waiting to see what he comes up with next.

"Prejudice always obscures the truth. I don’t really know what the truth is. I don’t suppose anybody will ever really know."

So speaks Henry Fonda's unnamed Juror No. 8, taking upon himself the seemingly impossible task of convincing his eleven peers to change their vote from "guilty" to "not guilty," thus sparing a young murder defendant the death penalty. 12 Angry Men was shot in a single room over 19 days for a mere $350,000. It was the director's first feature film, yet despite its marginal budget and modest setting it remains one of the most virile and enduring American movies ever made. It is truth – the search for essential truth – that has driven Lumet's sixty-year career and provided his 40+ films the same lasting power and relevance.

For Lumet, revelation of truth comes from a purity of vision. Often accused of lacking a signature directing style, his unpretentious approach is in fact a service to the film itself. Simply put, he allows the story to play out without distracting directorial flare. The scene in Dog Day Afternoon in which Al Pacino’s exhausted bank robber makes two phone calls – one to his wife, one to his transsexual lover – is shot in a single, uninterrupted take so that the raw emotion of that moment can stand on its own. In Network, Lumet follows crazed anchorman Peter Finch as he bellows his divinations to the masses; the simplicity of the camerawork gives an unobstructed view of how passionate pleas for humanity can be perverted into a cultural deadening by television executives hungry for ratings. Lumet often uses actual locations, usually gritty areas in his native New York. The more bare and realistic the setting, the better stage for his characters to seek resolution to conflicts afflicting them from outside and from within.

The enemy of truth is falsehood, and corruption runs rampant in Lumet's films: the corruption of institution (The Hill) and law enforcement (Serpico, Prince of the City), of basic human rights (The Verdict) and personal prejudice (12 Angry Men) threaten to dominate unchallenged. In the midst of these social injustices is an idealist forced to reevaluate his own principals and stand against the system. On the surface these protagonists are pitted against embodied obstacles, like the artificial "hill" Sean Connery’s interned British officer is forced to scale up and down in the blazing heat of the African desert. But in uncovering the falsehoods and hypocrisies of oppressive institutions, Lumet's heroes are really awakening something in themselves – something resembling humanity. Paul Newman's closing statement in The Verdict laments the victim of an indifferent medical facility but really sums up what Newman himself has come to realize: that his redemption lies in his ability to defend such victims. Lumet understands the world's overbearing cynicism, but believes that one man – or woman – finding himself harboring genuine goodness and honesty can prevail.

Lumet once summed up the theme of 12 Angry Men in a single word: "Listen." Communication (and lack thereof) plays heavily in the director's best films. To him, people's inability to properly communicate hinders any form of real understanding. In The Anderson Tapes (again starring Sean Connery, the actor worked with Lumet five times) wiretaps and security cameras piece together the story of a planned heist. However, since none of the surveillances are connected to the crime, the robbery isn't exposed until it's already been executed. Simple machines – responsible for the accidental incentive to nuclear war in Fail Safe and national popularity of "mad prophet" Howard Beale in Network – record, observe and even communicate, but they don't understand. Lumet sees machines as unfeeling tools, incapable of the reliable communication necessary for understanding truth. By relying on these inhuman sources the characters are lost: none of these three films end happily. It's only in finding compassion with their fellow men, as Fonda does by getting his fellow jurors to listen to his reasoning against a guilty verdict, that Lumet's heroes are able to topple the influence of callous, unfeeling systems.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of The Fugitive Kind, Lumet's adaptation of the Tennessee Williams play Orpheus Descending. In the film Marlon Brando plays a drifter drawn to Anna Magnani's older, embittered shop owner. Their tragic affair symbolizes, in Lumet's own words, "the struggle to preserve what is sensitive and vulnerable both in ourselves and in the world." That vulnerability applies in Lumet's films to the heads of state in Fail Safe, the representatives of the court system in 12 Angry Men and The Verdict and desperate criminals of Dog Day Afternoon. The difference between preserving this vulnerability and exposing it for the right reasons is what makes the people in Lumet's movies so flawed and fascinating, like Pacino's targeted cop Frank Serpico. For their work in the twelve films screening at the retrospective, ten actors received Academy Award nominations for their performances, a testament to Lumet's detailed, extended rehearsal process and the strength of these characters.

In 2007, Lumet turned 83. It would be impossible to tell from the sheer power and intelligence behind the masterful Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead, his most recent critically-lauded release. Philip Seymour Hoffman and Ethan Hawke play a pair of brothers who scheme to rob a jewelry store, a plot that leads to personal tragedy and ruin within their own family. In his 1983 film Daniel, the question was whether the political beliefs and sacrifices of the parents were worth the suffering handed down to their children. Running on Empty's River Phoenix is also forced to live his life based on the youthful actions of his fugitive parents, causing him to question whether constantly relocating and changing his identity is a fate he must suffer due to their mistakes. Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead inverts the question and asks if the needs and desires of the children should come at terrible price for the parents. Again it comes to down to that eternal need to understand, that essential truth – it permeates the films and has created in Sidney Lumet one of our most feeling and indispensable storytellers.

home about contact us featured writings years in review film productions

All rights reserved The Pink Smoke © 2011