In 1962 Bradbury wrote a nostalgic anti-nostalgia book, one composed of elegant paragraphs detailing the most romantic components of life as a young boy within a story that cautioned against yearning too desperately to get back to that age of carefree innocence. With that in mind, it's funny that I've been subconsciously ignoring this film for almost 20 years largely out of loyalty to the book, one that I read for the first time at the age of 13, same age as its two main characters, and have since revisited almost every October (although some years my annual autumn read is The Halloween Tree * - if I can I read both). This brainy girl I had a crush on in school once told me she refused to see Carroll Ballard's film of The Black Stallion because the visuals of the book were so clear in her mind she didn't want them corrupted by someone else's interpretation. That stuck with me, and subsequently I've never seen the movie versions of Slaughterhouse Five, Portnoy's Complaint, or Bridge to Terabithia because of the visual connection I have to those written works. It's not that I expect these films to be bad or not do justice to their source material per se, and I understand why the filmmakers wanted to adapt them - they had their own vision of the books that they wanted translated to the screen. It's just that there are certain visions of my own that I don't want to mesh with other people's, and that more or less is the reason why I've never seen the Disney-released 1983 version of Bradbury's Something Wicked This Way Comes.

In 1962 Bradbury wrote a nostalgic anti-nostalgia book, one composed of elegant paragraphs detailing the most romantic components of life as a young boy within a story that cautioned against yearning too desperately to get back to that age of carefree innocence. With that in mind, it's funny that I've been subconsciously ignoring this film for almost 20 years largely out of loyalty to the book, one that I read for the first time at the age of 13, same age as its two main characters, and have since revisited almost every October (although some years my annual autumn read is The Halloween Tree * - if I can I read both). This brainy girl I had a crush on in school once told me she refused to see Carroll Ballard's film of The Black Stallion because the visuals of the book were so clear in her mind she didn't want them corrupted by someone else's interpretation. That stuck with me, and subsequently I've never seen the movie versions of Slaughterhouse Five, Portnoy's Complaint, or Bridge to Terabithia because of the visual connection I have to those written works. It's not that I expect these films to be bad or not do justice to their source material per se, and I understand why the filmmakers wanted to adapt them - they had their own vision of the books that they wanted translated to the screen. It's just that there are certain visions of my own that I don't want to mesh with other people's, and that more or less is the reason why I've never seen the Disney-released 1983 version of Bradbury's Something Wicked This Way Comes.

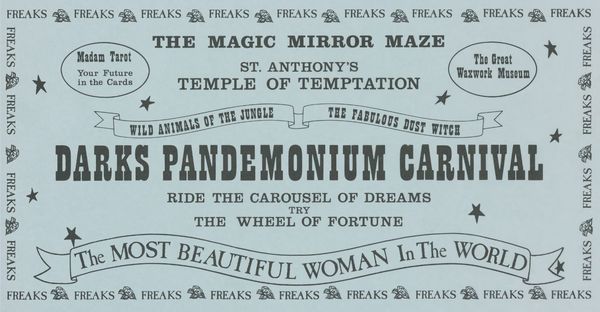

The book is made imminently readable by its language, which is unique even compared to the author's other works. The passages move like its adolescent protagonists, going up and down and running circles around an idea and ultimately flying off into another thought before settling on the one it was concentrating on or even finishing the sentence. It employs archaic dialogue that seeps into the descriptions, metaphors and stream of consciousness that would threaten to leave the reader behind if it weren't so lyrical. The real problem with falling in love with this book is that it may inspire you to try and write in the same kind of style, and you can't. You will fail and it will sound terrible. Every paragraph of Bradbury's novel is in danger of sounding terrible, but it doesn't because it's written by Ray Bradbury and he knows what he's doing. The story of an evil carnival that comes to a sleepy small town existing in some ideal time after the first World War and before the Great Depression one dark day in October is exciting enough on its own, but it's the flourishes of prose that make Something Wicked what it is. I wasn't sure I was ready to experience it any other way, even though I've inched close to it in the past: I've actually owned James Horner's soundtrack on LP for years even though I've never seen the movie, sometimes playing the record in the background while reading the book (Horner uses same "screech!..."screech!"..."screech! screech!" effect he'd revisit in Aliens).

I decided to finally watch the movie in honor of Bradbury Week (it was either this or A Sound of Thunder), and also because - speaking of Moby Dick - I was reminded of a recent viewing of John Huston's adaptation of Wise Blood. I've read Flannery O'Connor's book so many times that seeing Huston's movie was like sitting through a play: aw, lookit Brad Dourif all dressed up like Hazel Motes, it's so cute! I was so familiar with the source material that there was no chance of Huston's vision blocking mine out - I'm sure I'd feel the same way about his Moby Dick if I ever saw it, and was confident watching the movie version of Something Wicked would be no different. Besides, my knowledge of the Disney movie had already kind of seeped into my reading: knowing that Jonathan Pryce plays Mr. Dark makes it difficult not to put his voice to the dialogue in the book. And if the movie was bad it wouldn't matter, I would actually prefer that to it being more impressive than the power of my own goddamn imagination. I guess I was worried that it would be turn out to be "too good."

Turns out I didn't need to be. The movie has some nice touches that work, but as a whole it's an interesting failure at best, one of those early 80's fantasy films notable more for the weird touches the filmmakers added than the overall quality of the movie. Most of these touches are of the subversive "too extreme for kids!" variety: the dragon babies eating the princess alive in the PG-rated Dragonslayer, the Skeksis draining the life essence of the Gelflings in Jim Henson's The Dark Crystal, the sanitarium scenes and "Deadly Desert" from the Disney-released Return to Oz. In Something Wicked you've got a sinister redheaded carny transforming into a sinister ginger kid, a midnight tarantula attack, and a terrified young boy watching himself get guillotined, complete with decapitated child head. I can get behind those sort of edgy additions to what are ostensibly meant to be children's fare, and I like that era of Disney when Ron Miller decided instead of making the sixth or seventh Herbie movie they should branch out and produce such inspired if flawed oddities as The Watcher in the Woods, Never Cry Wolf and Tron. It has a reputation among those who grew up with it as being "really crazy," but I don't put much stake in that: we all know how that kind of movie, somebody else's childhood fave, inevitably turns out.

Back in the 70's Bradbury had given his blessing to direct the film to his friend Sam Peckinpah. As someone who believes it's not absurd to consider Peckinpah the greatest American filmmaker of the sound era, I have to confess to thinking that collaboration would have been a disaster. For one thing, besides the sadistic gang drowning the scorpion in the sea of ants in the first shots of The Wild Bunch, I can't think of a single child actor in any of Peckinpah's movies. For another, the director would have been genetically predisposed to fuck up any attempt at sentimentality or otherworldliness: it would have been an exercise in self-defeat. When it comes to Peckinpah I tend to picture brothels and seedy Mexican dives, not libraries and magic carnivals. More suited to the task was eventual helmer Jack Clayton, who seems like a great choice when you consider his 1961 Turn of the Screw adaptation The Innocents...not so much when you consider his 1974 The Great Gatsby adaptation The Great Gatsby. From the establishing shots of the town, filmed on a backlot with leaves blown in from offscreen, it's clear that Clayton is a very old-fashioned filmmaker who isn't going to bring much to the table that hadn't already been set for him. This is a problem - the story and writing is so stylized, the filming absolutely must be stylistic. It's not. It feels flat and fuddy duddy; it's static and indifferent.

The novel's two young heroes, Will Halloway and Jim Nightshade, are first shown in the movie sitting in a classroom, which is simply the wrong way to introduce them. In the book these two are constantly on the move, running from one adventure to the next, again as part of that rolling narrative that reads like it's racing after the duo as they chase the exciting events of autumn. So to open with the two sitting down just doesn't feel right. I don't want to spend this entire article pointing out how the movie fails where the book succeeds, but the boys and their movements are what drive the novel's narrative. The shot of them slumped over their desks in an empty school is indicative of the amount of energy the movie is feeding on; essentially, fumes. And the movie really needs that extra virility that its actors aren't supplying. The kids playing Jim and Will are just too young. I couldn't find a birthdate on either of them but there's no way either is 13 - they look 7, maybe 8. As such their bantering seems too aggressively mean, the subtlety of conveying resentment and jealousy mixed with genuine concern for each other is just too complex for these young fellas. The Funhouse's Shawn Carson (who I guess preferred acting in carnival-themed movies) is a particularly terrible choice for Nightshade. I know I'm 31 years old now (the inverted age of the book's characters) but I should still want to look up to Jim the way Will is supposed to, and Carson never looks cool and assured. Usually he looks like he's struggling to remember his marks. Full marks, however, for Brendan Klinger for his silent portrayal of evil Mr. Coogar in the form of a mischievous ginger kid. He looks positively surly, but this was his last credited role so maybe he just wasn't enjoying the filming experience.

The novel's two young heroes, Will Halloway and Jim Nightshade, are first shown in the movie sitting in a classroom, which is simply the wrong way to introduce them. In the book these two are constantly on the move, running from one adventure to the next, again as part of that rolling narrative that reads like it's racing after the duo as they chase the exciting events of autumn. So to open with the two sitting down just doesn't feel right. I don't want to spend this entire article pointing out how the movie fails where the book succeeds, but the boys and their movements are what drive the novel's narrative. The shot of them slumped over their desks in an empty school is indicative of the amount of energy the movie is feeding on; essentially, fumes. And the movie really needs that extra virility that its actors aren't supplying. The kids playing Jim and Will are just too young. I couldn't find a birthdate on either of them but there's no way either is 13 - they look 7, maybe 8. As such their bantering seems too aggressively mean, the subtlety of conveying resentment and jealousy mixed with genuine concern for each other is just too complex for these young fellas. The Funhouse's Shawn Carson (who I guess preferred acting in carnival-themed movies) is a particularly terrible choice for Nightshade. I know I'm 31 years old now (the inverted age of the book's characters) but I should still want to look up to Jim the way Will is supposed to, and Carson never looks cool and assured. Usually he looks like he's struggling to remember his marks. Full marks, however, for Brendan Klinger for his silent portrayal of evil Mr. Coogar in the form of a mischievous ginger kid. He looks positively surly, but this was his last credited role so maybe he just wasn't enjoying the filming experience.

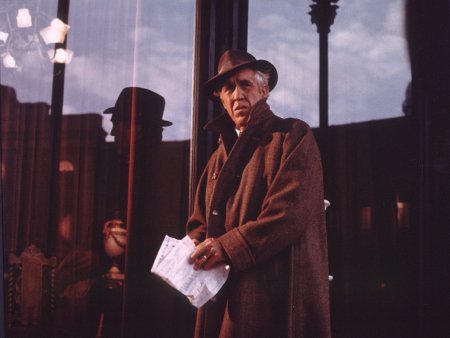

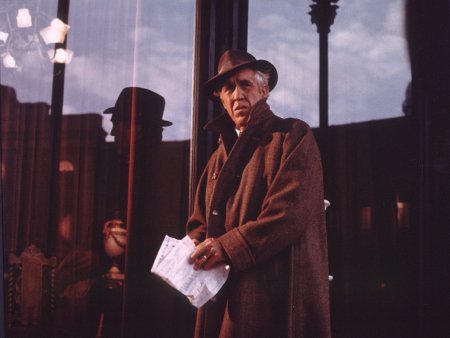

I've read some reviews that incorrectly claim Jason Robards plays Will's grandfather as opposed to father, an understandable mistake considering the revered film thespian never really gets a chance to bond with his son the way the character does in the book. That said, the best addition the screenplay makes is increasing the significance of Jim's absent father, and giving Robards a backstory of feeling regret that he failed to act to save his son's life in a near-drowning incident from years before (this isn't in the book if I'm remembering correctly, at least it's not a significant part of the book). Unfortunately though the script is repetitiously structured, falling into a loop around the middle where every scene does from action scene to a talk with Robards to another action scene and back to Robards etc. Making the character the official town librarian as opposed to the library janitor is something that might not seem like a big deal, but it's another thing about Charles Halloway from the book that makes him that much sadder: an old man surrounded by books after hours in the library who's not even the librarian?? That's almost unbearable!

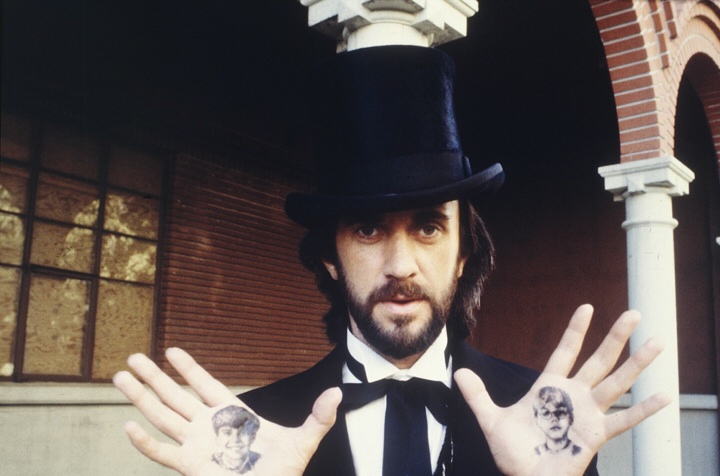

Of course the movie doesn't have a novel's amount of space to establish an entire population of bizarre carnival folk, but it still feels like the filmmakers didn't measure up in that department either. I have a better memory of some of the nameless freaks from the Penguin's posse in Batman Returns than the random small people and other assorted carnival types who appear in this film. The Crusher, the Lava Sipper, Monsieur Guillotine, the Skeleton, the Wart, Mr. Electrico (the freak who influenced Bradbury to write the story in the first place)...it's a pity to see them represented only half-assedly as background players. Pam Grier plays a character with basically the same role as the novel's Dust Witch and she lends an attractive menace to the proceedings, even when she's just sitting around (which is what she does most of her screen time). For his part Jonathan Pryce is very good in his first major performance, but like the child actors he feels a little young for the part - it's a shame that we'll never get to see Christopher Lee as Mr. Dark (Bradbury had also recommended Peter O'Toole to Disney, another good choice). The villains might have faired better onscreen if their scheme made more sense. They make a woman young again, but in a cruel ironic twist she also becomes...blind? I can understand if she was deaf and wanted to hear again, and they gave her back her hearing while taking her eyesight, that would be a harsh twist, but I can't connect her returned youth with losing her vision. And why do the bad guys need/fear lightning in the film? Again I don't want to base my thoughts on the film by simply comparing it to the superior novel, but these are basic plot points that simply don't make any sense.

Of course the movie doesn't have a novel's amount of space to establish an entire population of bizarre carnival folk, but it still feels like the filmmakers didn't measure up in that department either. I have a better memory of some of the nameless freaks from the Penguin's posse in Batman Returns than the random small people and other assorted carnival types who appear in this film. The Crusher, the Lava Sipper, Monsieur Guillotine, the Skeleton, the Wart, Mr. Electrico (the freak who influenced Bradbury to write the story in the first place)...it's a pity to see them represented only half-assedly as background players. Pam Grier plays a character with basically the same role as the novel's Dust Witch and she lends an attractive menace to the proceedings, even when she's just sitting around (which is what she does most of her screen time). For his part Jonathan Pryce is very good in his first major performance, but like the child actors he feels a little young for the part - it's a shame that we'll never get to see Christopher Lee as Mr. Dark (Bradbury had also recommended Peter O'Toole to Disney, another good choice). The villains might have faired better onscreen if their scheme made more sense. They make a woman young again, but in a cruel ironic twist she also becomes...blind? I can understand if she was deaf and wanted to hear again, and they gave her back her hearing while taking her eyesight, that would be a harsh twist, but I can't connect her returned youth with losing her vision. And why do the bad guys need/fear lightning in the film? Again I don't want to base my thoughts on the film by simply comparing it to the superior novel, but these are basic plot points that simply don't make any sense.

The movie's special effects are a point of contention between admirers and detractors: they've been criticized as cheesy and excessive but also praised by people who grew up with the film for posterity. I like the old school animation but unlike those in, say, It Came from Outer Space they're never utilized in a way that would make the film more interesting. I could see the animator's requisition form in every set-up, as in "insert here: creepy mist rising over train." Even so there are numerous occasions for the effects crew to heighten the more thrilling sequences, but like so many of their live action films from Blackbeard's Ghost on the Disney mentality seems to be "spiders = scary." In a long sequence around the midway point of the movie, the two boys are attacked in their rooms by dozens of the creepy crawlies care of Pam Grier. It's a terrible scene, not only ineffective but so disorienting it completely removed me from the movie. Not to mention nonsensical: in the book the carnies are looking for Will and Jim, forcing the boys to stop the Dust Witch from marking their houses. They succeed, leading to the hunting party disguised as a parade that scours the city searching for them the next day. In the movie, they're attacked at home so don't the carnies know where they live? Why bother with the parade facade? Was the spider attack a dream? How did they get out of there? This last question isn't answered for the simple reason that the scene is an obvious re-shoot. How do we know? The kids look five years older! I guess that's thematically relevant considering the book/movie is about all aging but that doesn't make it any less embarrassing. It's a real shame to lose the great Dust Witch sequence from the novel, the clever way the boys foil the carnies' plan, and how Charles outsmarts the witch later during the parade. I was impressed too with the Illustrated Man's moving tattoos, but we only see them once and they never appear again.

Produced while the author was in his sixties, this project was the first feature film to credit Bradbury as the sole screenwriter, even though confrontations with the studio and ultimately Clayton led to his script being rewritten by Tea with Mussolini's John Mortimer (father of Emily). I don't know his specific thoughts on the movie (I'm arranging to copy his audio commentary from a laser disc and will update this article after listening to it) other than his official declaration that it's "not a great film, no, but a decently nice one." I guess that's fair, although I'd say it's more of a nicely decent one. It doesn't stray too far away from Bradbury's original concept and tries its best to add a dark undertone to the story, yet most of it just feels like warmed-over television. The best scenes are straight from the book with surprising artistic relishes: the boys hiding below the grate during parade as the blood from Mr. Dark's clenched fist drips on Will's cheek, Dark in the library ripping out pages representing the ages Charles could go back to if he cooperated with the carnival. It's a shame they couldn't do much with the ending. I'll admit, the last chapter is the worst part of the book - they basically defeat the evil by hugging it and dancing around - but the drawn-out abstractions created by the effects department in the climax of the movie is very... well, the only word I can think of is "Disney." If you've seen the head-scratching conclusion of The Black Hole you'll have an idea what I'm talking about. They managed to make mirrors creepy in The Watcher in the Woods, but use them here only to disorient the viewer into thinking some kind of final showdown has taken place. Still...effects, adaptation, casting and direction being as flawed as they are, they serve as an example for the next visionary who inevitably takes a shot at bringing Bradbury's brilliant book to the screen. Mr. Bradbury, feel like ending this useless flirting with Mel Gibson over another Fahrenheit 451 and trying this one again?

~ AUGUST 25, 2010 ~

In 1962 Bradbury wrote a nostalgic anti-nostalgia book, one composed of elegant paragraphs detailing the most romantic components of life as a young boy within a story that cautioned against yearning too desperately to get back to that age of carefree innocence. With that in mind, it's funny that I've been subconsciously ignoring this film for almost 20 years largely out of loyalty to the book, one that I read for the first time at the age of 13, same age as its two main characters, and have since revisited almost every October (although some years my annual autumn read is The Halloween Tree * - if I can I read both). This brainy girl I had a crush on in school once told me she refused to see Carroll Ballard's film of The Black Stallion because the visuals of the book were so clear in her mind she didn't want them corrupted by someone else's interpretation. That stuck with me, and subsequently I've never seen the movie versions of Slaughterhouse Five, Portnoy's Complaint, or Bridge to Terabithia because of the visual connection I have to those written works. It's not that I expect these films to be bad or not do justice to their source material per se, and I understand why the filmmakers wanted to adapt them - they had their own vision of the books that they wanted translated to the screen. It's just that there are certain visions of my own that I don't want to mesh with other people's, and that more or less is the reason why I've never seen the Disney-released 1983 version of Bradbury's Something Wicked This Way Comes.

In 1962 Bradbury wrote a nostalgic anti-nostalgia book, one composed of elegant paragraphs detailing the most romantic components of life as a young boy within a story that cautioned against yearning too desperately to get back to that age of carefree innocence. With that in mind, it's funny that I've been subconsciously ignoring this film for almost 20 years largely out of loyalty to the book, one that I read for the first time at the age of 13, same age as its two main characters, and have since revisited almost every October (although some years my annual autumn read is The Halloween Tree * - if I can I read both). This brainy girl I had a crush on in school once told me she refused to see Carroll Ballard's film of The Black Stallion because the visuals of the book were so clear in her mind she didn't want them corrupted by someone else's interpretation. That stuck with me, and subsequently I've never seen the movie versions of Slaughterhouse Five, Portnoy's Complaint, or Bridge to Terabithia because of the visual connection I have to those written works. It's not that I expect these films to be bad or not do justice to their source material per se, and I understand why the filmmakers wanted to adapt them - they had their own vision of the books that they wanted translated to the screen. It's just that there are certain visions of my own that I don't want to mesh with other people's, and that more or less is the reason why I've never seen the Disney-released 1983 version of Bradbury's Something Wicked This Way Comes.

The novel's two young heroes, Will Halloway and Jim Nightshade, are first shown in the movie sitting in a classroom, which is simply the wrong way to introduce them. In the book these two are constantly on the move, running from one adventure to the next, again as part of that rolling narrative that reads like it's racing after the duo as they chase the exciting events of autumn. So to open with the two sitting down just doesn't feel right. I don't want to spend this entire article pointing out how the movie fails where the book succeeds, but the boys and their movements are what drive the novel's narrative. The shot of them slumped over their desks in an empty school is indicative of the amount of energy the movie is feeding on; essentially, fumes. And the movie really needs that extra virility that its actors aren't supplying. The kids playing Jim and Will are just too young. I couldn't find a birthdate on either of them but there's no way either is 13 - they look 7, maybe 8. As such their bantering seems too aggressively mean, the subtlety of conveying resentment and jealousy mixed with genuine concern for each other is just too complex for these young fellas. The Funhouse's Shawn Carson (who I guess preferred acting in carnival-themed movies) is a particularly terrible choice for Nightshade. I know I'm 31 years old now (the inverted age of the book's characters) but I should still want to look up to Jim the way Will is supposed to, and Carson never looks cool and assured. Usually he looks like he's struggling to remember his marks. Full marks, however, for Brendan Klinger for his silent portrayal of evil Mr. Coogar in the form of a mischievous ginger kid. He looks positively surly, but this was his last credited role so maybe he just wasn't enjoying the filming experience.

The novel's two young heroes, Will Halloway and Jim Nightshade, are first shown in the movie sitting in a classroom, which is simply the wrong way to introduce them. In the book these two are constantly on the move, running from one adventure to the next, again as part of that rolling narrative that reads like it's racing after the duo as they chase the exciting events of autumn. So to open with the two sitting down just doesn't feel right. I don't want to spend this entire article pointing out how the movie fails where the book succeeds, but the boys and their movements are what drive the novel's narrative. The shot of them slumped over their desks in an empty school is indicative of the amount of energy the movie is feeding on; essentially, fumes. And the movie really needs that extra virility that its actors aren't supplying. The kids playing Jim and Will are just too young. I couldn't find a birthdate on either of them but there's no way either is 13 - they look 7, maybe 8. As such their bantering seems too aggressively mean, the subtlety of conveying resentment and jealousy mixed with genuine concern for each other is just too complex for these young fellas. The Funhouse's Shawn Carson (who I guess preferred acting in carnival-themed movies) is a particularly terrible choice for Nightshade. I know I'm 31 years old now (the inverted age of the book's characters) but I should still want to look up to Jim the way Will is supposed to, and Carson never looks cool and assured. Usually he looks like he's struggling to remember his marks. Full marks, however, for Brendan Klinger for his silent portrayal of evil Mr. Coogar in the form of a mischievous ginger kid. He looks positively surly, but this was his last credited role so maybe he just wasn't enjoying the filming experience.  Of course the movie doesn't have a novel's amount of space to establish an entire population of bizarre carnival folk, but it still feels like the filmmakers didn't measure up in that department either. I have a better memory of some of the nameless freaks from the Penguin's posse in Batman Returns than the random small people and other assorted carnival types who appear in this film. The Crusher, the Lava Sipper, Monsieur Guillotine, the Skeleton, the Wart, Mr. Electrico (the freak who influenced Bradbury to write the story in the first place)...it's a pity to see them represented only half-assedly as background players. Pam Grier plays a character with basically the same role as the novel's Dust Witch and she lends an attractive menace to the proceedings, even when she's just sitting around (which is what she does most of her screen time). For his part Jonathan Pryce is very good in his first major performance, but like the child actors he feels a little young for the part - it's a shame that we'll never get to see Christopher Lee as Mr. Dark (Bradbury had also recommended Peter O'Toole to Disney, another good choice). The villains might have faired better onscreen if their scheme made more sense. They make a woman young again, but in a cruel ironic twist she also becomes...blind? I can understand if she was deaf and wanted to hear again, and they gave her back her hearing while taking her eyesight, that would be a harsh twist, but I can't connect her returned youth with losing her vision. And why do the bad guys need/fear lightning in the film? Again I don't want to base my thoughts on the film by simply comparing it to the superior novel, but these are basic plot points that simply don't make any sense.

Of course the movie doesn't have a novel's amount of space to establish an entire population of bizarre carnival folk, but it still feels like the filmmakers didn't measure up in that department either. I have a better memory of some of the nameless freaks from the Penguin's posse in Batman Returns than the random small people and other assorted carnival types who appear in this film. The Crusher, the Lava Sipper, Monsieur Guillotine, the Skeleton, the Wart, Mr. Electrico (the freak who influenced Bradbury to write the story in the first place)...it's a pity to see them represented only half-assedly as background players. Pam Grier plays a character with basically the same role as the novel's Dust Witch and she lends an attractive menace to the proceedings, even when she's just sitting around (which is what she does most of her screen time). For his part Jonathan Pryce is very good in his first major performance, but like the child actors he feels a little young for the part - it's a shame that we'll never get to see Christopher Lee as Mr. Dark (Bradbury had also recommended Peter O'Toole to Disney, another good choice). The villains might have faired better onscreen if their scheme made more sense. They make a woman young again, but in a cruel ironic twist she also becomes...blind? I can understand if she was deaf and wanted to hear again, and they gave her back her hearing while taking her eyesight, that would be a harsh twist, but I can't connect her returned youth with losing her vision. And why do the bad guys need/fear lightning in the film? Again I don't want to base my thoughts on the film by simply comparing it to the superior novel, but these are basic plot points that simply don't make any sense.