A FOREST OF SYMBOLS:

Following Errol Morris Into the Wilderness of Error

PART 2 by Christopher Funderburg

We swallow greedily any lie that flatters us, but we sip only little by little at a truth we find bitter.

Denis Diderot, probably not thinking about the relationship between evidence and narrative.

Circular Paths

In Part I, I explored how Errol Morris intends to rewrite the case, to save Jeffrey MacDonald from the narrative in which he's become imprisoned. The idea is to change the story from being the "Green Beret Murders" to something more along the lines of the "MacDonald Family Murders" and allow us to reconsider Jeffrey MacDonald not just as a suspect, but as a person. Morris is writing a new story, one in which the version laid out in Joel McGuiness' lurid true crime account Fatal Vision and MacDonald's questionable post-crime behavior are not the dominant focus.

The most convincing part of Morris' new story weaves around the theme, "Jeffrey MacDonald was persecuted with weak physical evidence." Morris has always been great with parsing minutiae and, while mentioning his past as private detective in the context of his art has become a cliché, it's easy to feel his former occupation in the systematic dismantling of the shaky evidence presented at trial and the borderline incompetent investigation. The unsatisfying aspect of Morris' reinvestigation (and its striking contrast to The Thin Blue Line) is that while he's able to tear down, he's not able to build up. He doesn't uncover anything exculpatory and can't fit the unexplained, ambiguous evidence he finds into anything resembling a conclusive narrative about what happened that night.

There's no revelation in his reinvestigation, only reevaluation.

He takes apart shaky evidence and digs up a host of loose ends, but doesn't build the loose ends into a new story. A Wilderness of Error seeks to write a convincing counter-narrative, the "Hippie Thrill Killers" story or the tale of the "Junkies Losing Control," but nothing ever materializes. Theoretically, a reinvestigation would be successful if two things happen in conjunction: a discounting of bad evidence/weak investigation clears the path for a new narrative and then extraneous, unconsidered or new evidence takes the investigation farther down that newly cleared path.

The first half of the equation, the path-clearing, happens quite well in Wilderness: when Morris is done tearing the work apart, nothing the investigators offered up as evidence of MacDonald's guilt stand in the way of Morris pursuing an avenue for MacDonald's innocence. The second half of the equation, though, is a non-starter: nothing Morris uncovers moves the case along in that direction of innocence. He opens the door that MacDonald could be innocent, but cannot move us through that door.

So much of Morris' book is dedicated to parsing this evidence that I can only give an abbreviated recap here. The night of the murders, military police are called to a crime scene by MacDonald from his military housing in Fort Bragg, North Carolina. MacDonald's wife and two daughters have been killed. MacDonald initially reports a stabbing (no mention of a home invasion) and police arrive at the scene believing they are coming to a domestic disturbance. They collect physical evidence while more or less disregarding MacDonald's on-site claims that a cabal of hippie lunatics showed up and in a drug-fueled orgy of violence brutally killed his entire family while leaving him significantly less harmed.

The major pieces of evidence collected at the scene include a three-foot piece of lumber found in the back yard likely used as a bludgeon, a kitchen knife likely used in the stabbings, a magazine found on the coffee table with an article on the Manson family, a t-shirt that MacDonald claimed to have used to defend himself from an ice pick-wielding attacker, the word "PIG" scrawled in blood on a bed's headboard and the ice pick believed to have been used to both puncture the t-shirt and stab MacDonald's 2-year-old daughter fifteen times. These pieces of evidence are "major" in the sense that they are the ones that most clearly factor into the dispute between MacDonald's version of events and the various case made by prosecutors.

There is also some important testimony from emergency responder Ken Mica, who claims to have seen a suspicious young woman hanging elsewhere on the base. This person's presence is weird for several reasons: it's raining out, it's late at night, she's a hippie-type and it's a military base. The CID investigators don't seem to have any interest in the young woman and don't make any significant effort to find her.

Apart from Mica, the main witness testimony comes from MacDonald, the lone survivor. His neighbors claim to have not heard anything - which is notable because it's a military base and the condos are packed tightly together, in townhouse-style apartments. This makes the investigators even more disinclined to believe his story: a gaggle of raucous drugged-out murder hippies probably should have been seen or heard by any of the neighbors.

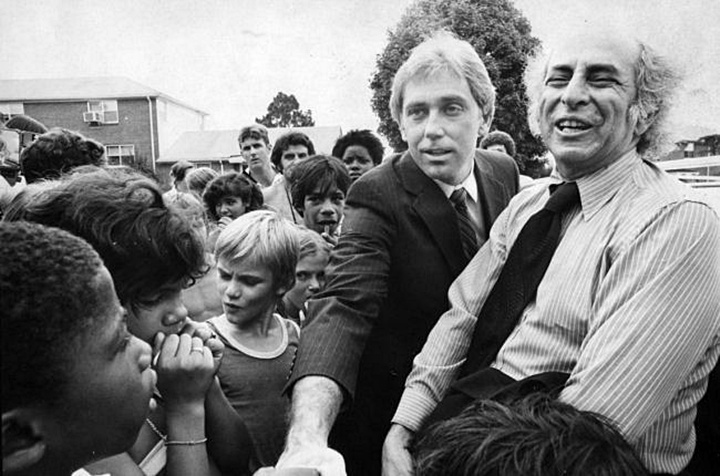

An internal military investigation follows and MacDonald becomes a minor cause célèbre, an upstanding protector of freedom fallen victim to the grotesque forces of the counter-culture. An Article 32 military trial ensues (with no jury) and the charges against MacDonald are found by overseer Colonel Warren Rock to be "not true." MacDonald's behavior after the trial upsets Alfred and Mildred Kassab, his wife's parents: he moves to California without telling them, buys a sports car and marries a young woman. He does a notorious interview with Dick Cavett and after that, the Kassabs begin pushing in earnest for MacDonald to be retried. Due to the efforts of the Kassabs, MacDonald is tried in federal court and found guilty.

The most damning piece of physical evidence at the federal trial is the shirt MacDonald claimed to have used defensively, which prosecutors purport to have been punctured in such a way that shows MacDonald created the perforations himself. The idea used to convict him goes: he lied about the shirt, he lied about defending himself from a home invasion, he wasn't gravely injured (suffering from a single stab wound that appeared calculatedly self-inflicted), he scrawled "PIG" on the headboard and the whole idea is a confabulation conjured up from the magazine found on his coffee table. The violence was all committed with implements found within the home, there is no testimony from neighbors supporting MacDonald's version of events.

It might be obvious to say that the first and most crucial link in the thought-chain used to convict MacDonald is the notion that he has lied about the shirt. That's why Morris goes to great lengths to demolish the prosecution's analysis of why MacDonald must have been the one to puncture the shirt - it's his attempt to make the entire chain break apart. But here's the problem: Morris proves that the statement "MacDonald is only person who could have punctured the shirt" is not true. He doesn't prove "MacDonald could not have caused the punctures."

So Morris clears a path towards innocence: someone else might have caused the punctures. But he doesn't move us down it - MacDonald still could have caused them. Morris does this repeatedly: there's an amusing section of the book where the boneheaded investigators are trying to figure out how the coffee table in the living room got set perfectly and precariously on its side edge. (MacDonald was supposedly sleeping on the couch while his family was being murdered and the struggle with the punctured t-shirt occurred there in the living room.)

Morris catalogues how the upturned table is alternately offered as proof of a struggle (the killers upturned it!), proof of a staged struggle (MacDonald upturned it!) and embarrassing evidence of a sloppy investigation (military investigators upturned it!) In Morris' telling, the table most convincingly serves as an illustrating that the investigators didn't know what they were doing, weren't paying attention and took confusing, contradictory notes. Obviously, this clears a lot of paths towards MacDonald's innocence. If the investigators aren't even sure what state the house was in when they arrived, how can any of the more ambiguous evidence they collected be taken seriously?

There's a second issue before we get to examine the evidence, a step farther back we need to take. "He's lying about the shirt!" is not the piece of evidence that causes MacDonald's case to be retried. What causes MacDonald's involvement in his family's murders to be reconsidered comes earlier: his behavior after the military trial in which he was found innocent. This is where the fonts in which MacDonald had thus far been written begin to come into conflict with their content. The "upstanding doctor" defending himself and his "beloved family" from "murderous hippies" doesn't square with his petulant, erratic post-CID investigation behavior. He begins to look like an obituary written in Comic Sans, l33t rendered in Baskerville.

MacDonald's post-trial behavior is weird. Morris admits it: "I have watched the Cavett interview alone and with others - some disposed to believe MacDonald is guilty, others that he's innocent. There is no argument. There is something weird about his affect." The t-shirt and the bad forensic science behind its meaning are not the source of Morris' interest in the case; MacDonald's weirdness and its meaning in his story, this is the root of Morris' reinvestigation. Morris believes MacDonald is a man damned for his behavior as much as he is damned by evidence. And it's an important thing to remember: a serious statement written in Comic Sans doesn't automatically become an untrue statement.

The parallels to The Thin Blue Line are once again unavoidable: Randall Adams' lack of remorse is cited in his sentencing as evidence of his danger to society and the need for him to be put to death. He's not acting "correctly." But of course he's not remorseful - he didn't murder that police officer! You can understand Morris' interest in MacDonald: here we have a man investigated for a crime and cleared by the Article 32 hearing, but unable to escape the shadow of suspicion simply because of how unsatisfying he is to others playing the role of surviving husband and father. His behavior is weird. It makes people uncomfortable. In discussing the Cavett appearance, Morris writes, "Just how is one supposed to act? Break down in tears? Demand vengeance?"

What is the proper way to respond to a tragedy? I'm very open to considering a case in this light and I think it's a very legitimate avenue for Morris to explore. In the New Yorker's seminal investigation of Cameron Todd Willingham's case, where a man was almost certainly erroneously put to death for the murder of his daughters, one of running themes is how Willingham's behavior gets interpreted differently by witnesses when they believe he's the victim of a tragedy versus when they have been led to believe by investigators that he's guilty of murder. It's easy to draw comparisons between Willingham and MacDonald, both cases where a sloppy initial investigation slams into a prosecution tainted by post-crime behavior.*

Morris wants us to step away from all that and consider the evidence, but with a caveat. The caveat is that the evidence is this case leads down a particularly circular route: Morris writes, "It is possible to cherry-pick evidence to support any conclusion. And it is possible to interpret evidence to support a conclusion." The evidence that appears to conclusively point towards MacDonald's guilt only appears to be evidence of guilt in light of the conclusion that MacDonald is guilty. For Morris, it again comes back to story: he asks his readers to consider the evidence not in light of the popular "Green Beret Murders" story, but from the vantage of his "MacDonald Family Murders" narrative.

So when Morris attacks, he attacks from a vantage, as much as he seems to be aiming for neutrality - Morris only considers evidence in light of how it might demonstrate MacDonald did not commit these crimes and never how it might point to MacDonald's guilt. This is not an unreasonable course of action, but keeping it in mind makes his successes seem that much thinner.

For example, Morris not only successfully calls into question the competence of the initial military investigation, but also makes a convincing case that MacDonald received wholly inadequate representation during the federal trial from his lawyer, Bernard Segal. Segal's ineffectuality (I hesitate to call it incompetence) does indeed seem to be as much of a factor in MacDonald's conviction as anything else. If considered from the perspective of the "MacDonald Family Murders," these successes have one meaning; from the perspective of the "Green Beret Murders," the exact opposite. One story tells of a man put behind bars by incompetence, the other of a killer potentially let free by it.

I'd like to mention that MacDonald's continuing loyalty (and even affection) for Segal is one of the book's stranger elements. MacDonald seems to have no awareness of the role Segal's miscalculations played in his ultimate conviction. But this is one of the ways in which the book is at odds with Morris' other work. He completely backs off the weirdness of this story and wants his readers to ignore all of the bizarre details that work against MacDonald. Films like Tabloid, Gates of Heaven, Vernon Florida, Fast Cheap and Out of Control and many of his First Person episodes luxuriate in the weirdness of their stories and characters - it wouldn't be outlandish to say that revealing insanity just below the surface of regular folks is Morris' trademark.

* One thing that bugs me deeply about A Wilderness of Error is how fast and loose it plays with the relationship between public perception of MacDonald and his conviction. In Part I, I mentioned how Fatal Vision came out after the conviction (which makes it nearly meaningless in the overall scheme of things, despite how much time Morris devotes to tearing it down). I'd also like to point out that one of the biggest blows to MacDonald's defense came when his attorneys were disallowed by federal judge Franklin T. Dupree Jr. to introduce dubious psychiatric testimony in his favor (the testimony essentially said, "this man is not the kind of person who would ever kill his family!") The judge didn't want the trial to be derailed by that sort of thing coming from either side, so one of Morris' biggest bugaboos doesn't even apply to the actual conviction.

<<Previous Page 1 2 Next Page>>

home about contact us featured writings years in review film productions

All rights reserved The Pink Smoke © 2015