A FOREST OF SYMBOLS:

Following Errol Morris Into the Wilderness of Error

PART 3 (page 2) by Christopher Funderburg

A name, a glove, a boot, a candle, a wig, a pair of scissors, a dress, an address for an accomplice - anything Helena Stoeckley could have reasonably added to advance the investigation never materializes. If she knew something, there's no evidence of it. All we know is that she changed her story once put on the witness stand. She clammed up, so she's either a perjurer or didn't want to risk perjury by testifying about something she knew nothing about. She lied repeatedly about the case, whether in confessions or retractions - that she lied repeatedly and offered testimony for personal gain are basically the only things about Helena Stoeckley that aren't in doubt.

Which brings us back to the surprise witness: first responder Ken Mica. [Pause for shocked courtroom to gasp!] En route to the MacDonald crime scene in his ambulance, Ken Mica noticed a woman in a wide-brimmed hat and boots standing alone in the rain several blocks away from his destination. When he arrived at the scene, he told the investigators that he had seen a woman matching the description MacDonald gave of his female assailant. The investigators blew him off, seemingly already convinced they had their man in MacDonald (again that being the scenario with the greatest likelihood.)*

A month later, Mica ran into MacDonald's mother at the post office and repeated his hippie sighting to her. The defense team and investigators alike went into action. A local cop tracked down Stoeckley, whose appearance he believed matched Mica's description of the mystery woman; Stoeckley began pussy-footing around confessing to her involvement. Mica, when asked about whether or not Stoeckley was the woman he had seen on the street, insisted that it was not her. No ambiguity. Stoeckley is a short, tubby, dowdy-looking drug addict (here's a clip of her). Was Mica sure it wasn't her? How did he know? In his words, from Wilderness: "Just a total different appearance. There was no resemblance. It just wasn't her." In another interview, Morris presses Mica on the issue. Mica points out he knew Stoeckley before the murders. Morris wants to know how he can be sure it wasn't Stoeckley. Mica replies "Well, I knew what she looked like, and I knew what the woman I saw that looked like. And they were just not even close."

Now, because of the wretchedly incompetent nature of the investigation and the hack-job crumminess of McGinniss' writing, I suppose I can understand Morris getting drawn into believing MacDonald's tale, even in spite of MacDonald's direct, on-the-record lies about who committed the murders.** If you believe MacDonald, then everything around Stoeckley's confessions begins to sound like damning coincidences. It becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy: if you are willing to entertain the idea that Stoeckley is telling the truth, then her story is tough to disbelieve.

But how could Morris cast doubt on Mica? Remember: investigators ignored Mica's account of a suspect matching the description given by MacDonald. They were caught up in the Scenario Most Likely and not interested in imaginary hippie thrill killers. Mica relayed his story in order to help MacDonald's defense - he told the man's mother what he saw just to make sure that the lead would be pursued. His actions were made on behalf of the defense. His story has never changed. He has never told a lie in regards to the case. There is zero, zero reason to doubt his account. Because of his truthfulness, consistency and interest in all leads being pursued, there is no reason to believe the woman he saw was Stoeckley. None. But that's what Morris does and in the most outlandish, silly hypocrisy in the whole damn book, he concocts the most false, psychologically presumptuous narrative of all. Look at this nonsense, these musings written by Morris that come just after a passage where Morris transcribes Mica relating his unwavering tale to a documentary film crew:

We are constantly struggling to make our beliefs fit together. Imagine Ken Mica on his way to 544 Castle Drive. He sees a woman standing in the light rain, but he and his partner keep on driving to the house. He wonders: Who was she? At first he was pressured to deny he had seen anything. But conscience got the better of him, and he told MacDonald's mother and his attorneys what he had seen and testified to that fact at the Article 32 hearing. It is only in the decades since that that impression has been replaced.

Wait, what the hell?

Just what impression had been replaced? Mica never denied seeing a woman in a hat on the road. He testified under oath to that effect and did so, as Morris points out, despite being "pressured to deny he had seen anything." He identified that woman on the road as not being Helena Stoeckley.

What impression is Morris referencing?

It doesn't make any sense.

There's only one context in which Morris' statement is even intelligible: if you dismiss an untruth (the untruth that Helena Stoeckley is the woman Ken Mica saw on the road), the whole precarious thing that is the argument for MacDonald's innocence collapses. Since Stoeckley isn't the woman Mica saw, there's no reason to believe any of her account. The coincidences begin to look like conveniences, empty confessions begin to look like the tools of a professional tattler. In regards to Mica and Morris' fanciful rumination on his testimony, Morris is the only one who appears to be operating under false impressions. Just re-reading it, I feel ashamed for Morris.

There are three crucial narratives in the MacDonald case. Two are told by proven liars who had something to gain by lying. One is told by a man who maintained a steady truth in the face of governmental resistance. A Wilderness of Error hinges on believing the liars and dismissing the truth-teller. I can't for the life of me figure out why.

That's not true. I know exactly why and just can't believe one of my heroes would stoop this low: if you remove Stoeckley from the equation, there's almost nothing to Morris' new investigation. Without Stoeckley, A Wilderness of Error would be nothing but so many empty pages. A couple bits of black wool, a 2-inch brown hair and a 22-inch saran fiber, some mislabeled samples and an intransigent judge. It's nothing. Without Stoeckly being the woman Mica saw in the rain, the book is a failure. Do you believe Mica? Or Stoeckly? It becomes the same question as "do you believe MacDonald?"

Psychosis

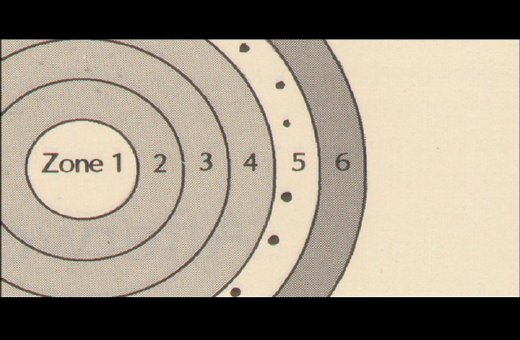

What troubles both Morris and me the most about the case can be found in the psychologizing of the crucial players and how the analysis of their psyches is used to create stories that damn them. Morris spends a healthy chunk of the beginning of the book going through the various accounts of the psychological analyses done on MacDonald. This is a cherished bug-a-boo for Morris, who first stumbled across The Thin Blue Line's Randall Adams while researching James "Dr. Death" Grigson. Grigson was a notorious prosecution witness in Texas brought in during the penalty phase to declare the guilty party a dangerous psychopath who the jury would live to regret not giving the maximum punishment allowable by law, if they so foolishly failed to do so. He would arrive at this ironclad diagnosis after a cursory evaluation session that consisted of little more than a few puzzles and word association tests. Adams had been damned by Dr. Death.

This kind of cheap psychological analysis drives Morris crazy: he's mentioned it in countless interviews, it's evidenced directly in The Thin Blue Line and the "Mr. Personality" episode of his First Person TV series about Dr. Michael Stone, who developed a truly absurd personality test used to size up the psychological profile of criminal offenders. Throughout Wilderness, Morris rightfully harps on this theme: MacDonald's post-murder behavior resulted in a catch-22. He was a psychopath because he didn't act like a psychopath. That no one in his life thought him deranged or capable of such a crime proved just how maliciously deviant he truly was: like all true psychopaths, he hid behind a mask of sanity. Morris tears apart these damning narratives rendered from a simplistic version of complex human psychology. MacDonald's options were to act like a malevolent nutjob and be damned as such, or act like a regular joe and be damned for psychopathy.

Morris' desecrations of sacred psychobabble are so forceful and effective that when he begins to trot out positive analyses of MacDonald, it stopped me dead in my tracks. Now, hold on one second - if I shouldn't believe the negative diagnosis of MacDonald for being hollow and too convenient, why should I buy into the equally hollow and convenient positive diagnosis? On what basis are the new opinions being rendered? Morris blows a hole in an entire field of criminal psychology and then doesn't bother to repair the damage before trying to use it to his new story's advantage. I can't take the positive verdicts on MacDonald's sanity at face value because Morris has so thoroughly undermined the mechanisms by which these verdicts are rendered in every case. It's yet another bad example of how I felt like Morris was talking out of both sides of his mouth throughout the book.

Morris is one of the greatest filmmakers who ever lived and deserves my utmost respect in all things - those facts only served to up the level of my frustration with his lack of consistency. After tearing down the discipline, he throws out the sentiment (almost as a given) that new doctors said MacDonald was fine, totally not a psychopath at all. He doesn't elucidate us as to what tests were done to arrive at the new conclusion or discuss the circumstances in which his new doctors are generally employed as witnesses and evaluators. Since he's spent such a significant amount of his book on pulling apart the very concept of psychopathy as it exists in a criminal context, it just doesn't track to accept a positive analysis without discussion or rigorous inspection. At some point, I realized I hadn't read a description of the symptoms of psychopathy that Morris would accept (and therefore could be used to rule out MacDonald as a candidate for the classification) - if we're going to satisfactorily declare MacDonald "not a psychopath," don't we need a solid definition beyond the ones Morris has kicked the shit out of?

Worse still, in these later sections with all the Dr. Goodvibes speaking on MacDonald's behalf, when we are finally offered a cursory description of the symptoms of psychopathy, it turns out several of them do apply to MacDonald. A doctor named Rex Beaber says "a psychopath has a very specific kind of history: engaging in illegal conduct, poor performance in school, conduct disorders as a child, disrespect for authority, failure to learn from experience, frequent long-term affairs, drug and substance abuse..." Wait, hold on one second: in his brief interview with Morris, MacDonald mentions his infidelities and says of them such: "You know, my great sin in life is that I had a couple of one-night stands. Who didn't in the sixties?" Who hasn't had an affair? Is that really what he's asking? Try thousands upon thousands of people including your murdered wife and I bet Mr. Errol Morris himself. It's the traditional "lack of remorse" and long-term infidelities in one grotesque package. He cheated on his dead wife and doesn't even feel bad about it!

Also, doesn't MacDonald's loyalty to his incompetent lawyer and total lack of self-awareness fit comfortably into the whole "failure to learn from past mistakes" criteria? He's still out there giving the kind of interviews he gave to Dick Cavett. MacDonald's constant ranting about being railroaded and tirades against the prosecutors certainly fit that bill as far as "disrespect for authority" is concerned. But again, Morris doesn't offer any rigorous inspection of what that list of characteristics means, what behaviors might qualify or how anyone might comfortably come to the conclusion that they definitely don't apply to MacDonald. It's such a hypocritical maneuver on Morris' part.

The mention of drug abuse is interesting - not only for how it ties into the definition of a psychopath, but for how drugs floated around the periphery of the entire case, the murders being drug-related serving as one of the more likely scenarios for exonerating MacDonald. One of the bombshells in Fatal Vision is McGinniss' discovery that MacDonald had been downing 3-to-5 capsules of dextroamphetamine a day in the 3-4 weeks prior to the murders, resulting in a weight-loss of 12-15 pounds. Yep. You read that right: at the time of the murders, Jeffery MacDonald was tweaking on speed as part of a shock-loss weight management regimen.

Doctors strictly recommend against losing more than 3 pounds a week because of its significant physiological effects and, incidentally, they also consider heavy amphetamine use*** to be drug and/or substance abuse. Morris totally blows off this angle - it's even listed in the book's appendix under "alleged amphetamine use." First off, the only person "alleging" this use of speed is MacDonald himself - McGinniss gets it directly from a MacDonald's diary. Morris seems utterly clueless about drug use: he writes, "If MacDonald, a highly trained emergency room physician had overdosed on amphetamine, wouldn't he be aware of that fact?" That's his response to McGinniss pointing out that hospital workers had noted MacDonald's withdrawal symptoms in his time there after the murders.

It's a ludicrous position for Morris to take - why wouldn't the highly trained physicians treating MacDonald be aware of the facts of amphetamine withdrawal? Good ol' Dr. Beaber attempts to downplay the importance of MacDonald's drug abuse by saying "abuse of stimulant medications**** amongst physicians, especially physicians who do emergency work...is extremely common." These are doctors, folks - they are exempt from having drug problems. It's one of the book's more shameful passages, the attempt to erase the relationship between drug abuse and erratic, criminal behavior, as if being high out of your mind has no effect on your decision-making, irritability and rationality while responsible, doctorly drug usage is of zero consequence.

This is another example of drug issues where I just don't get the sense that Morris understands what it means to be high on speed for weeks at a time. Also, as someone who lost 60 pounds over the course of 3 months, I can tell you that extreme weight-loss does insane things to your mind and body. And I lost it without tweaking on amphetamines for 3-4 weeks straight. The drug addiction provides another component for a diagnosis of psychopathy and Morris disregards it, as though it's totally innocuous and the suggestion that MacDonald had his mind and body effected by drugs is absurd. There's physical proof of the effects right there in MacDonald's own journal: extreme weight-loss! We know the drugs were affecting MacDonald because of MacDonald's own measurements of their massive effect.

MacDonald decisively meets a significant portion of the criteria for a diagnosis of psychopathy and Morris ignores it. Does one need to fit all the criteria to be considered a psychopath? Does MacDonald's constant public display of contempt for the courts, lawyers and police count as "disrespect for authority?" Does his drug abuse count as "engaging in illegal conduct?"***** His "failure to learn from experience" and "conduct disorders as a child" remain unexplored as Morris once again shies away from MacDonald as a subject.

When Morris interviews the attorney overseeing MacDonald's appeals, the lawyer makes a show of how he's never even met MacDonald and thinks it's best to not even know him. I get the sense that Morris feels the same way - he wants to write the story of the "MacDonald Family Murders" but not have to deal with Jeffrey MacDonald. As a filmmaker, Morris is famous for his use of an invention of his own devising, the Interrotron, which allows his subjects to look directly into the camera and engage in largely uninterrupted monologues. With A Wilderness of Error, Morris refuses to look MacDonald in the eye.

In their brief conference call that comes eyebrow-raisingly late in the book, Morris speaks roughly as much as MacDonald himself and uses the opportunity to express head-on his book's themes about objective truth and the sky's indisputable blueness.****** Even in this brief chat (it runs three pages total in the hardcover - for comparison, the nonsense with the utterly irrelevant Rex Beaber runs well over a page), MacDonald manages to shoot himself in the foot repeatedly, not only with a jaw-dropping unsolicited aside about his extramarital affairs, but his analysis of what went wrong during the trial. He doesn't seem in any way concerned with Stoeckley, but rather obsessed with fighting the judge and slandering the psychiatrist who gave him a damning evaluation. If you had sympathy for him up until this point, I can't imagine sustaining it after his unprompted digression about the joy of getting remarried yet again while in jail. It's the Cavett interview all over again - what is up with this guy? Of course Morris wants to hide him from plain sight.

That's the biggest problem with the case: MacDonald does not do himself any favors. He feels deeply indebted to the idiotic lawyer who torpedoed his chances, he allows McGinniss total access to his life, he has a terrible feel for how he comes across in conversation and hurts himself even worse in public forums. To a certain extent, Morris is right that some of these issues should be off-limits; at very least, they shouldn't dominate the discussion of the case to the extent they have. But at the same time, Morris argues that the question of MacDonald's motivation for killing his family is an open issue. That's where hiding MacDonald from his own story gets more than a little dicey. If the idea is that this is a story about stories and there needs to be a new, fairer one written for MacDonald, trying to keep MacDonald out of it feels unsettling if not outright dishonest.

If we consider scenarios and their likelihoods, it's not hard to see how MacDonald fits in - husbands kill their wives with sickening regularity, parents kill their children with sickening regularity. Drug-addicted, philandering husbands kill their wives. There are plenty of cases where this happens without a prior history of violence, without a prior history of criminality. Add this to the story: a man taking 3-5 methamphetamine tablets for 3-4 weeks to engage in extreme weight loss. A man who works two jobs to stay afloat financially. A man who tells his wife's stepfather and mother lies about who killed their daughter. A man who moves across the country without informing his wife's surviving family. A man who immediately gets a new girlfriend and buys a sports car. A man who never expresses public interest in the tragedy that befell his family, but takes every opportunity to decry the injustices he has suffered. A man who has affairs and feels no remorse. A man who possesses some of the attributes of a psychopath. An inciting incident when his daughter wets the bed. A drug-intensified rage, a liar, an outlandish story of Manson copycat home invasion. An adulterer who buys a new sports car and marries a beautiful new wife. Black wool fibers, a 22-inch saran fiber, a 2-inch brown hair. I wish there were a better story to be told. I really do.

* In reviewing this article, John Cribbs (who is also a fan of Morris and shares my dubious feelings re: his book) pointed out that it's not even clear that MacDonald mentioned the hippie in a floppy hat before Mica reported to investigators that he had seen a suspicious woman standing outside. Furthermore, MacDonald was in the room with the investigators as Mica discussed the suspicious woman. So, the mysterious woman on the street and her connection to murders, which is so crucial to verifying MacDonald's story, are details that might not have even come originally from MacDonald!

** Is this confusing? Again, I mean he said he found the real killer - that is a direct lie about the person who killed his family.

*** Mixed with compazine as a stabilizer! It's an anti-psychotic normally used to treat schizophrenics! Side effects include hallucinatory dreams, an inability to sleep, irritability, anxiety and severe headaches. But this man was a doctor, so there's no way drugs played a factor in the crime.

**** These are medications, people - these doctors are not drug addicts. It is medication.

***** Not to get tautological, but the murders would certainly be evidence of engaging in illegal conduct. If that's the final piece needed for a diagnosis, does missing that piece alone mean he can't be diagnosed as a psychopath?

****** One of Morris' favorite concepts comes from discussing his film about electric-chair repairman turned Holocaust denier Fred Leuchter, Jr. In his initial cut of the film he made about Leuchter, Mr. Death, Morris didn't waste a single frame refuting the bad science Leuchter employed to irrefutably "prove" Ernst Zundel's claim that cyanide gas was never used in the gas chambers at Auschwitz and Birkenau. In his words, he didn't set out to "prove the sky is blue." But some early, pre-release audiences found Leuchter's work to be convincing, so Morris had to add a ten minute section tearing down the worthless science behind Leuchter's assertions. The idea of the sky's indisputable blueness is a metaphor for Morris' belief in objective reality to which he frequently returns - the sky is blue, the Holocaust happened, Randall Adams didn't kill a police officer. He makes several references to blue skies in his dialog with MacDonald.

Related Articles

<<Previous Page 1 2 Next Page>>

home about contact us featured writings years in review film productions

All rights reserved The Pink Smoke © 2015