DOUBLE PORTRAiT

& SEASCAPE

~by martin kessler~

dedicated to M.C.

At the risk of dating this article...

It was with great excitement that my girlfriend and I threw caution to the wind just prior to the first COVID-19 pandemic lockdown to go and see the 2020 adaptation of Jane Austen’s Emma, directed by Autumn de Wilde and starring Anya Taylor-Joy. As of writing this, it’s still my last trip to a genuine movie theatre. It was a wonderful experience getting wrapped up in the film’s bright colours, sharp sense of humour, and peculiar faces which all give a very entertaining impression of a bygone age. A little like the characters in that film, in the time that’s followed I’ve oft found myself all dressed up with nowhere to go.

In the year that’s followed my girlfriend and I have watched a lot of these sorts of costume dramas together. That certain variety of mild, froufrou film or show that is usually set in Western Europe and span anywhen from the Renaissance to the early 20th century, but is probably best exemplified by British stories, typically of the Georgian, Regency, Victorian, and Edwardian eras. These are of course distinct time periods, but they can all be a part of a cohesive cinematic genre. They can be fictional or based on real people and events, but either way they’re mostly focused on the personal problems of the fancily-dressed class of people who live mostly in a state of leisure. Often those films are described as being “Austenesque” (I myself prefer the less literary “Jane Austen-ey,”) and occasionally they even include the odd actual Jane Austen adaptation. They can be incredibly comforting, but watching these films I found myself asking questions about the relationship between art, subject, artist, audience, and their place in society in both the past and the present.

My girlfriend happens to be Black. That she is Black isn’t the sort of thing that I usually spend much time contemplating, but watching these sorts of films and shows I can feel a nagging awareness seep in. She can trace her background all the way back to the “triangle trade,” in which Britain was a major player in the commerce of human slavery. According to historian Professor Alan Rice, that was a point in time during the peak of the British slave trade in the 18th century, when the largest slave port in the world was Liverpool. It’s a horrific period of time which overlaps with many of these typically gentle, dignified costume dramas, and with some awareness of this, a tension emerges. For the majority of these films there aren’t any Black people to be found at all, but when a Black actor does appear on screen they’re typically playing a maid, servant, or slave... barely characters at all, when treated as more than a background presence. They’re essentially ancillary to the main (white) characters.1

Sometimes you see attempts to justify the backgrounding or absence of Black characters in this type of film under the guise of historical accuracy (a misconception I’ll soon dig further into), like for instance with the film Downton Abbey (2019), whose executive producer Gareth Neame insisted that “Britain was not a multicultural country in 1920,” and whose director Michael Engler stated "We weren't just going to change it for political correctness... you just have to learn about that world and then try to portray it as realistic,” when questioned about this particular issue. I think anyone who takes a moment to think about Britain at that time being the heart of a global colonial empire will probably realize the naivety of believing Britain was monocultural.2 Julian Fellowes, who is an honest-to-goodness British Lord in addition to being the creator of the show that Downton Abbey is based on, writer of the costume dramas Gosford Park (2001), The Young Victoria (2009), and who co-adapted the 2004 version of Vanity Fair, would make it clear that he was in favour of diversity in film and television... except when it came to period dramas.

This mindset has created a well-known vacuum of opportunity for Black European actors and actresses when it comes to these Austenesque endeavours, which (along with mystery dramas) might be regarded as the bread and butter of the British film and television industry. English actress Thandiwe (Thandie) Newton commented on this restrictiveness in a 2017 interview with Katie Glass for The Sunday Times, stating "I love being in the UK, but I can’t work, because I can’t do Downton Abbey, can’t be in Victoria, can’t be in Call the Midwife. Well, I could, but I don’t want to play someone who’s being racially abused.” Newton has of course been in numerous period dramas that she fits perfectly well in like The Journey of August King (1995), Jefferson in Paris (1995), Beloved (1998), albeit playing Americans.

I should clarify that this is not meant to be a casting advocacy piece. There’s plenty of writing on that already (and I’m not looking to score woke points or whatever). Instead I’m more interested in exploring some of the artistic and historical issues that this trend seems to be a symptom of. I should also probably take an aside to clarify that while I may be critical of many Austenesque movies and shows in regards to this article, Jane Austen herself I unequivocally let off the hook. It’s probably worth mentioning that Austen even included a specifically Black woman as a principal character in her final novel Sanditon. That character is Miss Lambe, a wealthy heiress of delicate health from the West Indies, and the most eligible young lady in town. Unfortunately Sanditon was never finished due to Austen’s untimely death, however it was recently adapted for the first time in a PBS series of the same title in 2019, for which screenwriter Andrew Davies imagined a plot for the rest of the story that Austen had established.

To be fair, the series Sanditon has been a part of a notable pushback in recent years against long-standing wrongheaded attitudes surrounding costume dramas, though many recent examples that are meant to counter this outlook, like the television show Bridgerton take a “colourblind” approach by ignoring the nuances of the racial politics of historical periods, or even casting Black actors in the roles of historical figures who were not Black, like for instance in the casting of Adrian Lester to play Lord Thomas Randolph in Mary Queen of Scots (2018), or the upcoming mini-series Anne Boleyn which stars Jodie Turner-Smith as the doomed queen. While I think this sort of casting comes from a well-intentioned place and I often enjoy seeing how particular actors perform these roles,3 it may have the unintended consequence of further burying the history of Black experiences and of the lives of real Black historical figures. There have already been well-written critiques of these works on these grounds, like for instance Marlene L. Duat’s January 19, 2021 article “Why Did Bridgerton Erase Haiti?” for Avidly.

I think this approach to depicting Black people in historical settings is as if to say that the only place for Black people in costume dramas is in an anarchistic fantasy or a fictionalized distortion of history. To me it’s obvious this approach as far as achieving any sort of revisionist perspective of European history seems ineffectual, especially when contrasted with the more readily available depictions of Black American histories in cinema and television (like for instance Barry Jenkins’ superb new series The Underground Railroad).4 I think it’s important to artistically explore just how varied Black history can be because what might be considered “The Black Experience” isn’t monolithic, and is nuanced partly because of the many varied cultures, experiences, and histories that fall under that umbrella term.5

I suspect many misconceptions about history in general are carried into costume dramas, because those films and shows echo the art and pop culture imagery of the periods they set out to portray. It’s easy to find European paintings from various periods in history doing exactly what films today could be criticized for.

Elihu Yale with Members of his Family and an Enslaved Child (c. 1719) attributed to John Verelst.

It makes me pause to wonder how consequently our visual understanding of history is often defined by the representations of the artwork of a particular epoch, which has typically been shaped and curated by the upper-class of the day. The most celebrated costume dramas, like Barry Lyndon, are invariably praised for how much they resemble the paintings from the period they are set during. What are we really getting from these paintings? Should we be more wary of adhering as closely to them as we can and calling it historical accuracy? This seems especially vital when considering the lives of people who were pushed into the shadows of history.

The Raikes Family (1730-1732) by Gawen Hamilton.

With that in mind I think it then becomes worth taking a look at paintings that (intentionally or not) challenged the prevailing narratives of their day, and consequently for this article, films that draw consideration or inspiration from them to do the same today.

SUBJECT

This concern of artist representation is very much the heart of Belle (2013), a film that could be said to be based on a painting. There’s a moment early in the movie when the main character as a child, Dido Elizabeth Belle Lindsay, a real Black historical figure who lived in England during the Georgian era, looks up to a portrait of her white father, Captain Sir John Lindsay. Then gradually her gaze lowers to a Black child posed in the painting much like a prop to stare adoringly at him. It establishes an anxiety in her about her place in the society around her, which is further compounded by other similar images shown throughout the film. The artwork is telling her much the same thing that films made today which are inspired by such artwork continue to say. The director of Belle, Amma Asante described attending an art exhibition in Holland prior to making the film, which informed her emphasis on the artwork of the period, saying “what it showed me was that in the 18th century, we were accessories...when I say we, people of colour were accessories. So we were there to express the status of the main Caucasian protagonist in the painting. We were always painted lower down. We were never looking out, or very rarely looking out at the painter. We were always looking up at the main protagonist, with our arm reaching out towards them, which would draw your eye towards them.”6 The film gives a strong sense of that overbearing feeling of artistic depictions pushing to reinforce her position in British society.

While her father was a Scottish-born nobleman who’d be knighted for his bravery and leadership as a naval officer, Dido’s mother was an African slave who was named Maria Bell, who was perhaps liberated or captured (the exact verbiage depends on who you ask) from a Spanish vessel in the Caribbean by Captain Lindsay, but even that little is uncertain, as virtually nothing is known today about Maria Bell. Dido (who is played by Gugu Mbatha-Raw) wasn’t raised by either parent; her mother died when she was very young, and her father sent her to live with and be raised by his uncle and aunt; William Murray, the Lord Mansfield, and his wife, the Lady Mansfield (who in the film are played by Tom Wilkinson and Emily Watson respectively). Dido would have been considered illegitimate, but her father’s legal recognition of her before his death secured a comfortable future for her as an heiress. Lord and Lady Mansfield already had one niece in their care before Dido arrived, Elizabeth Murray (played by Sarah Gadon in the film) who was left with them following the death of her own mother when her father, the formidable politician David Murray, essentially disowned her when he remarried. The cousins Dido and Elizabeth were close to the same age and raised very much as sisters, and seeing their relationship captured on screen is one of the highlights of Belle.

The script for Belle went through many changes. At one point a version was titled “Belle and Bette” and apparently told a story that evenly balanced the lives of the cousin-sisters, though I think it was a wise decision to focus more on Dido because her life provides an opportunity to examine issues found at the junction of art, history, class, and ethnicity in an entirely organic way. Like many of my favourite films that deconstruct a genre, Belle is also an exemplary entry in that genre. I think it’s a “have your cake and eat it too” situation with Belle being able to examine subjects that costume dramas typically tip-toe around or obliviously trample right over, while still meeting the expectations of a costume drama. After all, it seems easy to break the appeal of most costume dramas... the “which suitor will she choose,” or “who will inherit the estate,” and that sort of thing... when an audience is being reminded of weighty subjects like Britain’s prominent and brutal involvement in colonialism and role in the slave trade, with all the human suffering, and ethnic and cultural debris left in its wake. After all, these Austenesque movies are supposed to be romantic, breezy, and fun!

Truly, Belle is as Jane Austen-ey as they come. Much of the film revolves around Dido choosing one of two potential suitors, one an upper-class man who sees her skin colour as something to look past, and the other a working-class man who loves her for who she is. I’m sure you can guess which one she chooses. It doesn’t work to only love half of someone, does it? That love rivalry goes along with all the other sorts of things someone would look for in these sorts of films; the romance, the beautiful colourful costumes, the sweeping Rachel Portman score... it’s exactly what you want out of a costume drama. I’m tempted to call it a real costume-ass-costume drama.

It might be worth contrasting the spirited and colourful Belle with something like Abdellatif Kechiche’s controversial film Black Venus (2010), which depicts the life of Sarah Baartman (played by Yahima Torres), a South African Woman who was known as “the Hottentot Venus” in Europe, where she was exhibited, objectified, and even in death was subject to dehumanizing scrutiny. Black Venus is a film that successfully critiques a whitewashed perspective of European history, but it’s also such a deliberately dim, drab, miserable, and ruthlessly stoic movie that any provocation in the realm of the costume drama as a genre ends up feeling muted.

Often a deconstruction that comes from a loving place can be the most effective, and there’s no doubt that Belle comes from a loving place. Prior to becoming involved with making Belle, Amma Asante had even tried to make a film adaptation of Jane Austen’s short novel, Lady Susan, which would eventually be adapted instead by Whit Stillman into the film Love & Friendship (2016). At a talk for Google, Asante made it clear exactly what her approach for Belle was, stating, “For me it was important that if I was going to tell a movie that was Austenesque and that looked at genteel society, that I also looked at the world that was funding that society, and the economy of that society, and the trade that was sponsoring that society, and that was the slave trade. So it was very important for me to keep it Austenesque, but also make sure that the impact of slavery hit.”

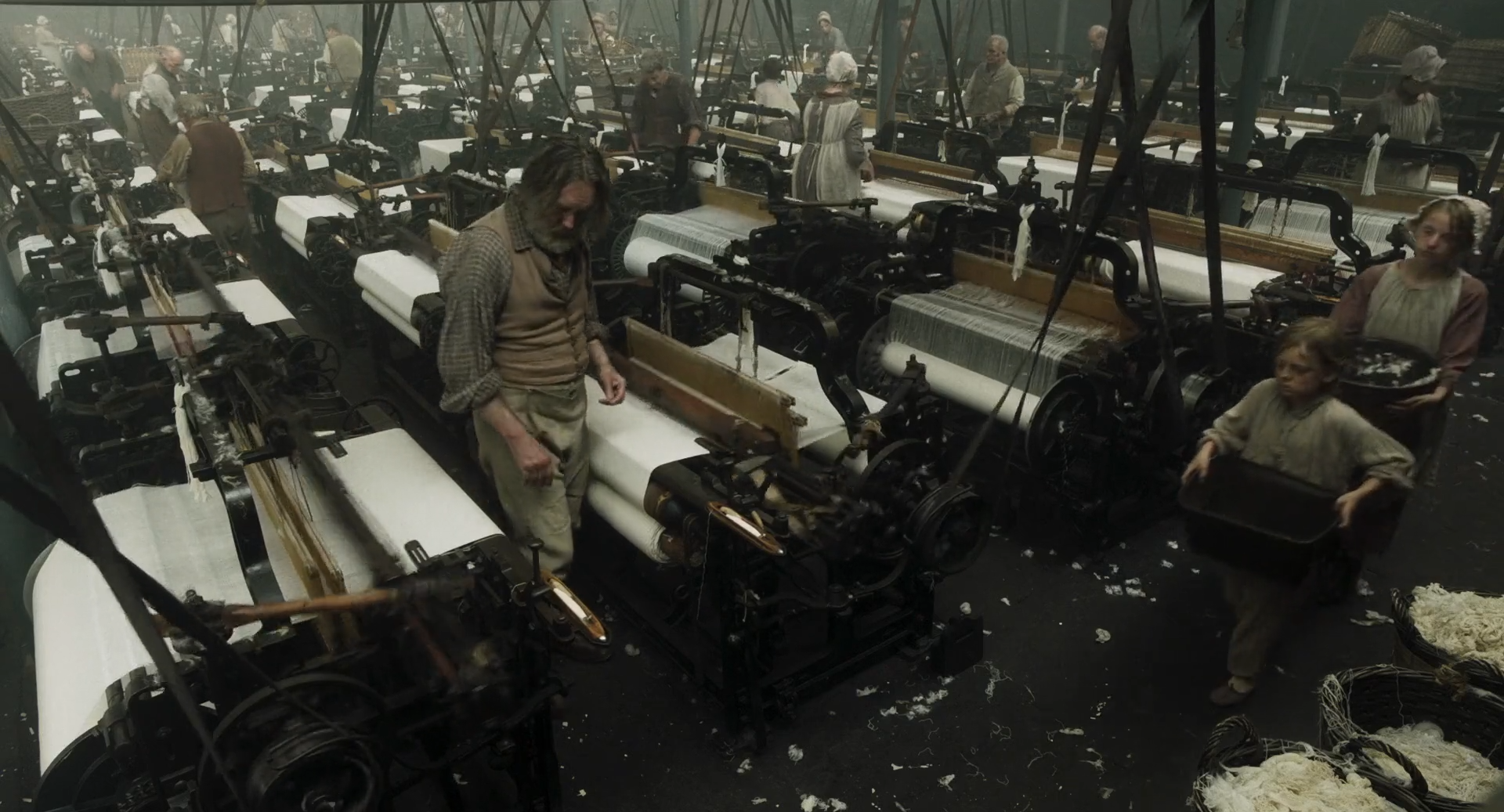

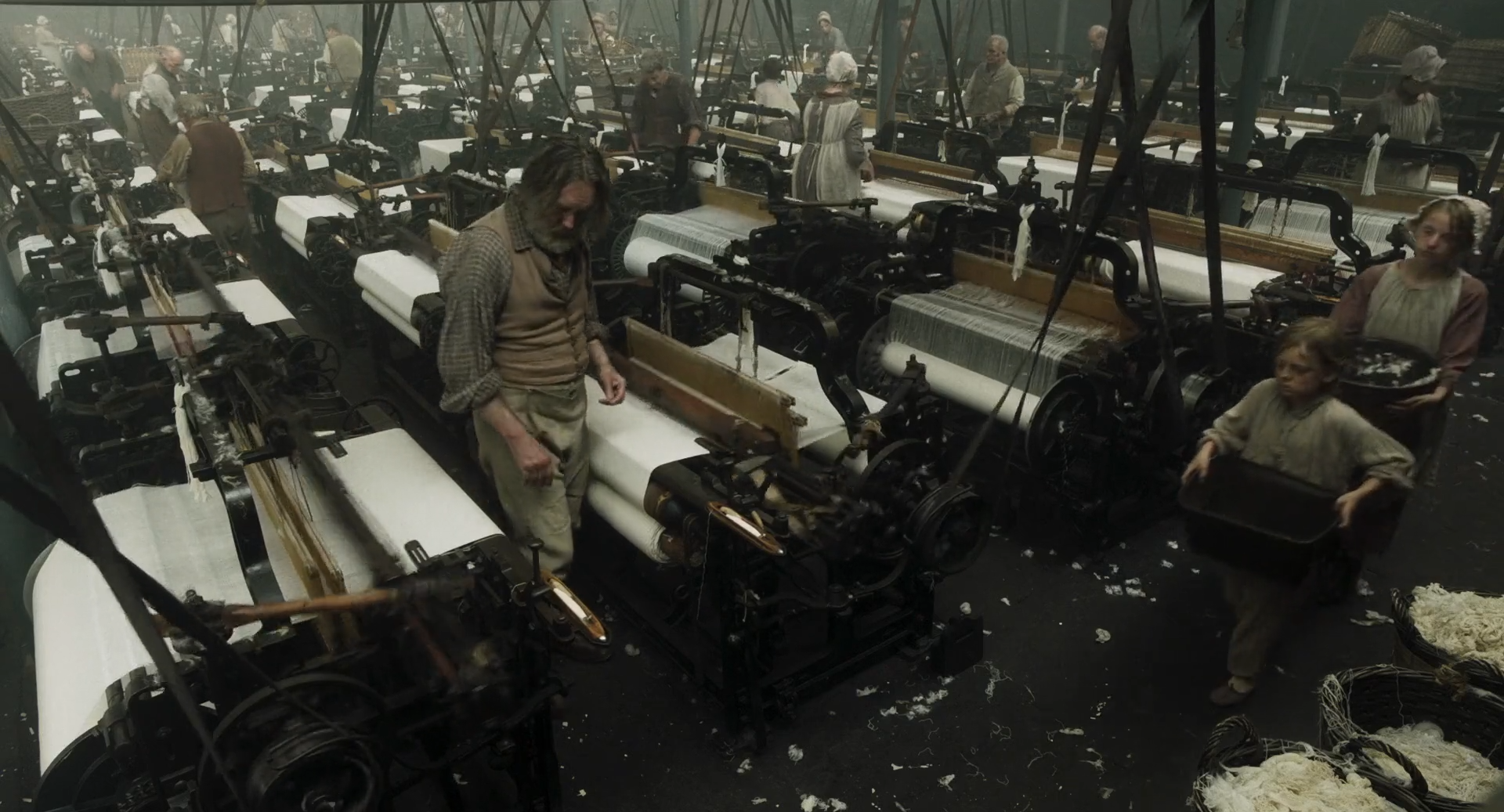

It’s perhaps something to keep in mind that those wondrous dresses and outfits, which are in a way at the heart of costume dramas, largely owed their existence to the influx of inexpensive cotton yielded from the labour of slaves. Slavery was even a major catalyst in the onset of the industrial revolution, with that inexpensive cotton creating a necessity for industrial-scale textile production, like what arose in the world’s first industrialized city, Manchester. You can see that textile production in Manchester during the era before the abolition of slavery depicted in Mike Leigh’s Peterloo (2018), a film which is about an 1819 rally for parliamentary representation that was violently crushed by the British government. While Peterloo doesn’t directly touch on the legacy of race-based slavery, it is a film that is very much about Britain’s history of class-based oppression, and by looking at the economic history (or “following the money” if you prefer) in what the film shows, it becomes possible to get a sense of the deep interconnectedness of issues of “race” and class in British history.7 An interesting aspect of Belle is that its subject further complicates this relationship.

It was a seemingly contradictory position that Dido found herself in, being the daughter of a slave as well as illegitimate, but also an heiress in a well-to-do noble family. She had a quality of life above the vast majority of Black people in Britain at that time, but still remained an outsider in the upper-class. Her exact place in class-fixated British society is a focal point of Belle, and the film doesn’t shy away from touching on the absurdities brought about by her position, like for instance how when guests would come over for dinner Dido would be considered too high in rank to eat with the servants, but too low in rank to eat with everyone else. You can imagine how alienated an experience Dido may have lived. I think of how deeply, cruelly, oppressive the concept of societal shame is, both past and present. In the film, when Dido turns down a marriage proposal into an upper-class family, she gives as her reason, “You view my circumstances as unfortunate, though I cannot claim even a portion of the misfortune to those whom I most closely resemble. My greatest misfortune would be to marry into a family who would carry me as their shame, as I have been required to carry my own mother.”

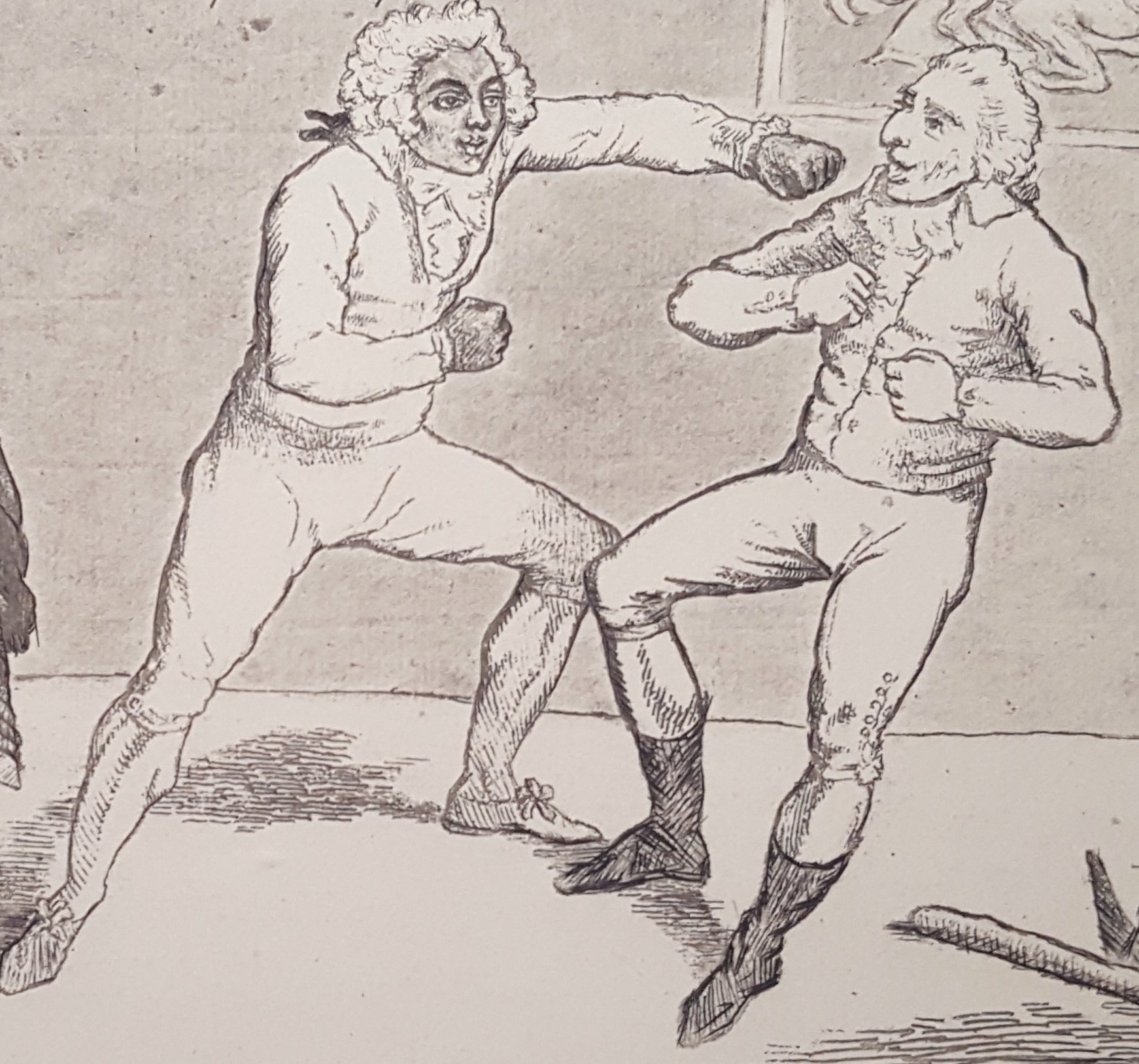

While exceptional, Dido’s position as a Black person in the European upperclass was not wholly unique to that time. Despite limited representation in media both past and present, there were numerous other men and women in European history who found themselves with similar mixed heritage and accepted by their noble families. One example would be the 18th century savant composer, Joseph Bologne the Chevalier de Saint-Georges, whose adventurous life would certainly warrant a biopic.8

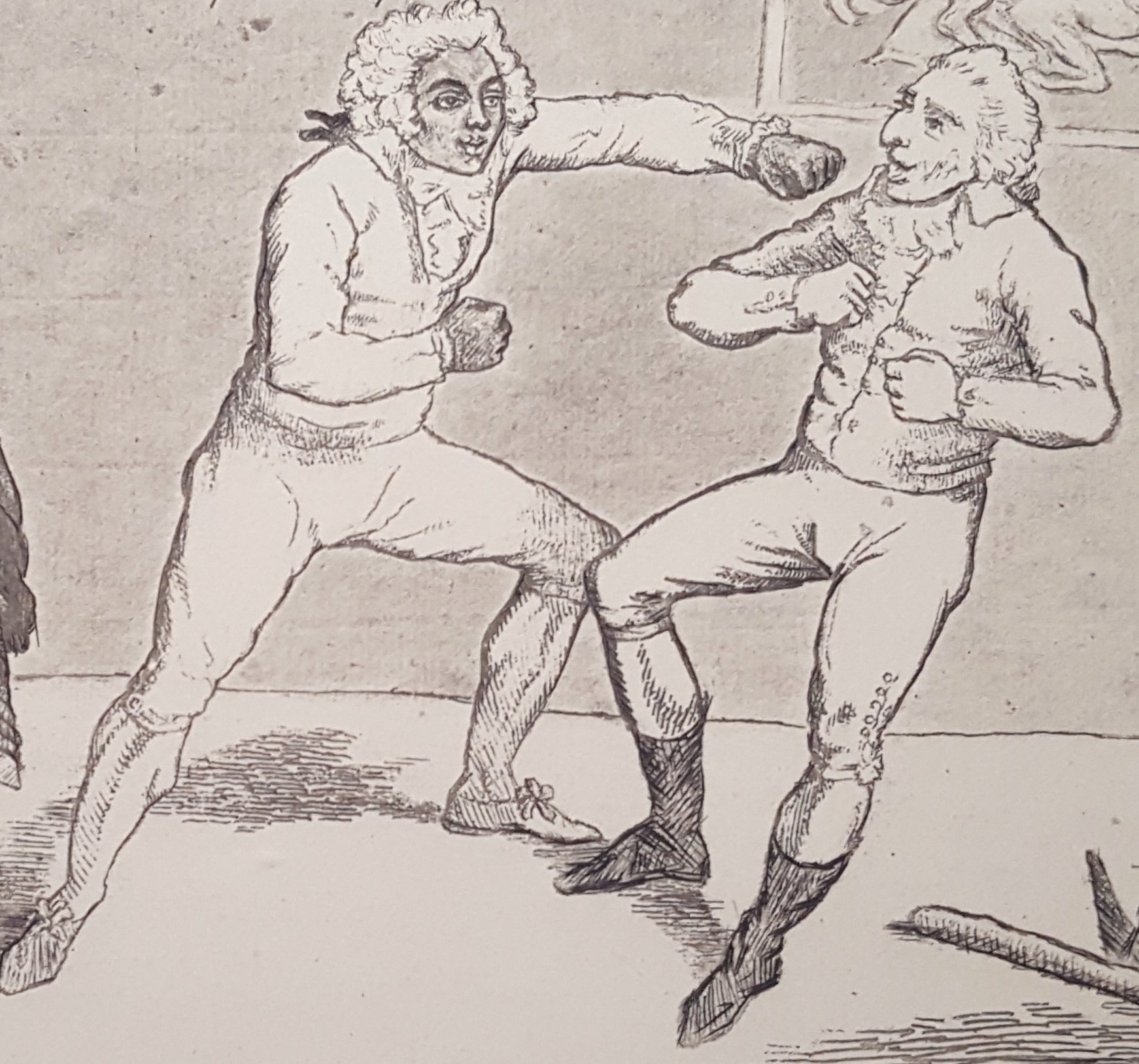

Joseph Bologne boxing the shit out of one Colonel Hanger in a 1789 London Morning Post cartoon.

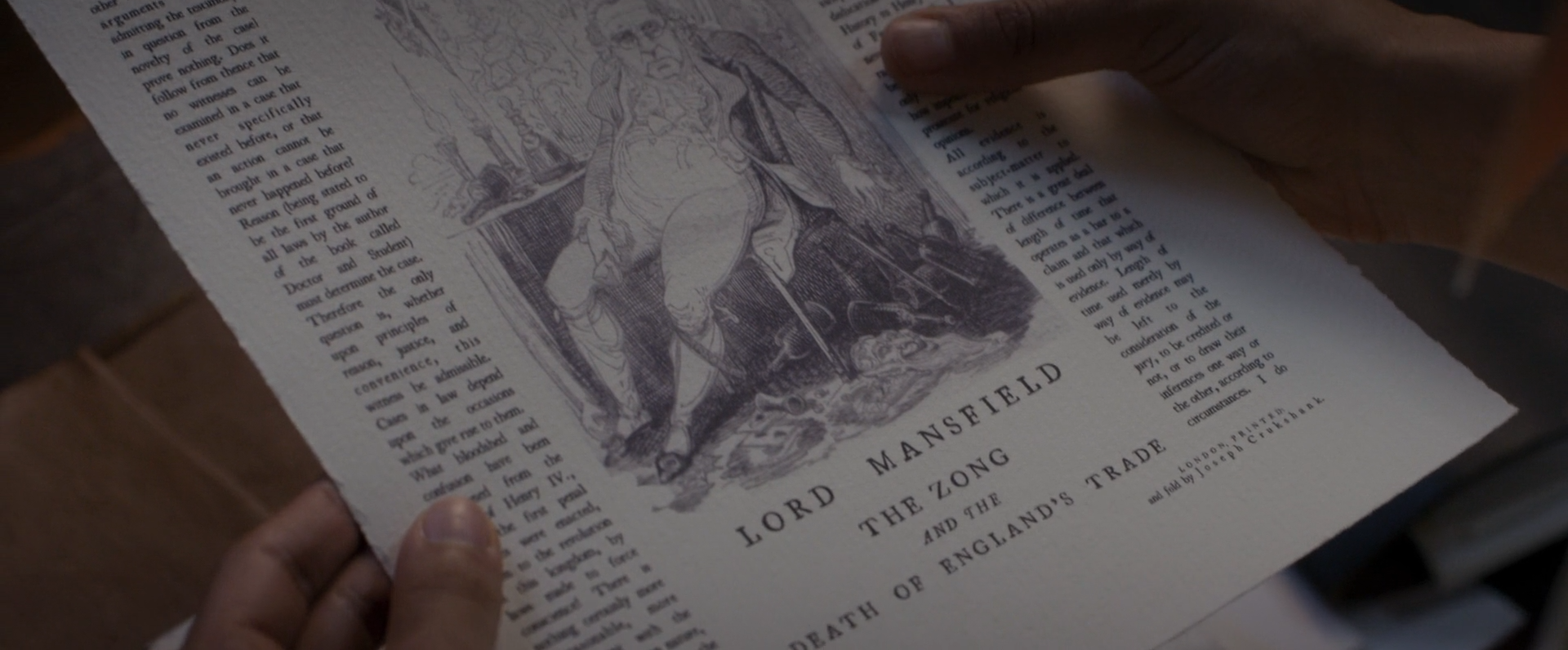

What was unique to Dido was that she was raised by Lord Mansfield who would play a notable role in the push towards ending Britain’s involvement in the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. Lord Mansfield had relatively humble beginnings (at least by the standards of Scottish-born nobility), but he would eventually work his way up to Chief Justice of England (like a one-man supreme court), and perhaps the most historically important case he presided over was the notorious Zong insurance case.

The Zong case revolved around slavers trying to collect insurance on over 130 insured African slaves who had been murdered on the slave ship Zong by deliberate drowning. While Lord Mansfield’s judgment of the case didn’t have any bearing on the actual legality of the slave trade, it threatened the economic feasibility of the slave trade, and consequently the status quo of the upperclass peer group Mansfield had worked so hard to be accepted by. He was under enormous pressure by powerful people invested in the slave trade (including lobbyists from the newly independent United States) to side in favour of the slavers.

There’s even a first hand description of Dido from around that time, recorded in the diary of Thomas Hutchinson, who had previously been the Governor of Massachusetts during the time of the Boston Tea Party incident, and who at the time of this account was a prominent figure in the group of exiled American loyalists living in England. After having dinner with Lord Mansfield when he intended to push his agenda, he saw Dido and wrote in the sort of language you might expect:

... a black came in after dinner and sat with the ladies, and after coffee, walked with the company in the gardens, one of the young ladies having her arm within the other. She had a very high cap, and her wool was much frizzled in her neck, but not enough to answer the large curls now in fashion. She is neither handsome nor genteel—pert enough. I knew her history before, but my Lord mentioned it again. Sir John Lindsay having taken her mother prisoner in a Spanish vessel, brought her to England, where she was delivered of this girl, of which she was then with child, and which was taken care of by Lord M., and has been educated by his family. He calls her Dido, which I suppose is all the name she has. He knows he has been reproached for showing a fondness for her, I dare say not criminal.

The Zong insurance case is the major historical event that the film Belle is set against, with Dido’s grand-uncle’s legal decision being at the crux of the story. There is some significant compression of the historical timeline and futzing with details for the film, but I consider them to be excusable conceits to find a narrative that a conventional dramatic film can be built upon. After all, Dido’s contribution to history, and why someone would want to make a film about her isn’t so much anything that she did like you might expect from a historical biopic. Again, details of her life are scant, but that she lived and was a part of - even at the epicentre of - a changing society, and that evidence remains for it, is what’s important. I recognize that that’s not easy to dramatize though, so I don’t really mind some fictionalization to get a broader perspective on her place in that society. Even the change of her working-class love interest and future husband, John Davinier from a valet (butler) to an idealistic lawyer with abolitionist inclinations for narrative tidiness I can understand, though I’d second guess why the French John Davinier (as his last name might suggest) was changed to being English (and portrayed by Australian actor Sam Reid). Can’t the idealistic hunky young lawyer be French?

Anyway, while apparently some versions of the screenplay did include what would have been images of the dead and dying left in the wake of the slave ship Zong, I think it was a smart choice for Belle to not depict the The Zong Massacre directly, and instead restrict representations of it entirely to what Dido would have had access to, having to piece together through whispers and scraps of ephemera, the existence and significance of a legal case she’s simultaneously inherently connected to, while also being shielded from because of her class and Lord Mansfield’s protectiveness of her. It shows her reliance on the restricted images and whispers to expand her understanding of the case and perspective on the wider world around her, and it subtly emphasizes the necessity of representing not only status-quo-challenging narratives in art and pop culture, but also access to them.

In Belle, Dido finding out about the Zong case is a catalyst for her growing societal awareness. She begins to question the values of the supposedly genteel society around her and if she even wants to be fully accepted by it at all. There are characters in the film who aid in that questioning, like the aforementioned John Davinier, but another is Mable (played by Bethan Mary-James), a character invented for the film. She’s a servant first introduced when Lord Mansfield brings Dido and the rest of his family to stay in London while he judges the Zong case. There’s an immediate non-verbal connection between Dido and Mable, expressed through eye contact; a sort of mutual acknowledgement of being visually identifiable outsiders in London. It reminds me of a similar, brief moment in Terrence Malick’s The New World (2005), when the Powhatan princess Pocahontas encounters a Black man in London and there’s a moment of fascination with one another’s anomalousness, as if to wordlessly communicate to one another, “... and yet here we are.”

One of the most quietly moving scenes in Belle is when Mable sees Dido struggling with combing her own hair, and intervenes to show her how to comb her hair starting from the ends. Despite their difference in social status, there’s a sense of sorority between these two women, and in a way Mable functions as a mirror for Dido, realizing how she could have easily been in a dramatically different part of British society but for the capriciousness of fate.

In a follow-up scene Dido asks Lord Mansfield over breakfast, “Is Mable a slave?”

“She is free and under our protection.” Lord Mansfield reassures her.

“Oh, like me,” a line which Gugu Mbatha-Raw injects full of sarcasm. It’s an exchange that astutely highlights the importance of being in a privileged position in a society and seeing one’s self in others not in that same position, and using that to question, criticize, and ideally change that society for the better. Often I find conversations of issues related to privilege and empowerment don’t fully delve into the moral responsibilities that empowerment might entail. This conundrum I think was well explored in the 2016 film Lady Macbeth, an adaptation of Nikolai Leskov’s novella Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District.9 Set in northern England in the 19th century, the journey of Lady Lester (played by Florence Pugh) is certainly one of empowerment in a male-dominated society, but in the casting of mixed-race and Black actors in key roles who are exploited or destroyed by the Lady in her journey to a position of power, the film offers a potent critique. Probably the most disturbing moment in the film comes at the climax, with the framing of the mute maid Anna (played by Naomi Ackie) and condemning her to death, simply for the Lady to cover her own previous unscrupulous actions and secure her position of power on the estate. So perhaps a takeaway from this particular adaptation could be said to be something a little like, “yes, this white women was treated as second class citizen, but she had more social power than Black men and Black women in this society, and was perfectly capable of using her power to abuse and exploit rather than uplift and improve the world around her.”

DOUBLE PORTRAiT

In Belle, Dido’s anxiety of artistic representation and her place in her society come to a head when she finds out that she’s to be painted alongside Elizabeth in a double-portrait commissioned by Lord Mansfield. It’s easy to sympathize with her dread of being portrayed as a prop for her cousin-sister after seeing the artwork Dido has been surrounded by.

Simultaneously there’s a parallel suspense built in the film over Lord Mansfield’s judgment over the Zong case. Mansfield is portrayed as someone being very established and invested in British institutions and notions of class, who is faced with a moral decision where the right choice might throw those institutions into disarray because of their investment in slavery and racist policies.

Of course with his stepdaughter in mind, he makes the right choice at the end of the film and finds in favour of the insurers. He even utters the maxim that the real Lord Mandfield famously spoke, "Let justice be done though the heavens fall” in his judgment on the Zong insurance case, which has a wonderfully “to Hell with it” ring to it, and underscored how the only way for justice to be served in an unjust society is to disrupt that society. While slavery wouldn’t be officially outlawed in Britain until a number of years after Lord Mansfield’s death,10 his judgment dealt a massive practical blow to the slave trade, by making insurance an uncertainty rendering it a much more economically risky venture. The real Lord Mansfield certainly maintained the inscrutable appearance of objectivity, though there’s much reason to be suspicious that he may have been something of a closet abolitionist. About a decade earlier Lord Mansfield had ruled on the similarly impactful Somerset v. Stewart case, in which he ruled in favour of James Somerset, an African man who had escaped slavery from a Bostonian customs officer and who faced the threat of being forcefully deported to be re-enslaved. The ruling on that case was considered a benchmark, even though experts argue over the exact precedent it sent. It seems that it made clear that American slave laws were not applicable on British soil. With the Somerset v. Stewart case in mind, I suspect that Lord Mansfield’s ruling wasn’t out of the blue, and can easily imagine a lawyer for the slavers banging their head against a wall when finding out who would be judging the case.

The trial’s conclusion represents a climax to the film’s examination of the more overt social-political issues addressed, but there’s also a parallel more intimate relief for both Dido and the audience, when the double portrait is unveiled and she’s portrayed not as a prop or accessory for Elizabeth, but rather as her equal and an individual. It’s here that we get to the real painting that inspired the film...

Double portraits like this were usually only for spouses and close family relations like a mother and child, or two sisters, so I think with that in mind, Dido and Elizabeth are presented as sisters in the artwork. It’s intriguing to note not only the obvious juxtapositions between the two cousin-sisters, but also the similarities. There’s something about their eyes and noses, that I think may be a tip-off that they’re related, regardless of their difference in complexion. Elizabeth appears more bookish and demure, while Dido appears more lively and sly, maybe even a little capricious. Perhaps one could have been described as having “sense” and the other having “sensibility,” with the sisters Elinor and Marianne of Jane Austen’s famous novel Sense and Sensibility particularly in mind. There are no surviving words written by the cousin-sisters to get a sense if these characterizations are accurate. Someone else looking at this same painting may have a different take on them, and I think of how different my impression of Dido is from this painting is compared to the characterization of a less care-free woman that Gugu Mbatha-Raw brought to life in the film. It is of course only my interpretation of the artist’s interoperation of them, so those characterizations may not have been true to the young women depicted, but really the artistic interpretation is what’s important when it comes to this topic. It’s the way that they are represented that seems key. Art can be a powerful conduit to the past, and I want to try to find meaning in these people through this painting.

Looking at the painting I’m reminded of some of the blended families I know, where strong bonds of love have formed across familial craters induced by tragedy or dysfunction. I’m also reminded of a contemporary-set Mike Leigh film, Secrets & Lies (1996), at end of that film when the two half-sisters (one played by Marianne Jean-Baptiste and the other by Claire Rushbrook), are properly united for the first time and there’s a sense that in spite of the emotional pain caused by the film’s titular secrets and lies, there’s something unambiguously good in these two young women being brought together for the first time and agreeing not to let any petty societal notion of shame repress the truth of their connection.

The painting is also subject to a few controversies I’ll briefly touch on. For starters, Dido’s name would be omitted from the painting for most of its history. Later generations would be ignorant of their relation to Dido, and a 1904 inventory of the painting would even describe it as “Lady Elizabeth Finch-Hatton with a Negress Attendant.” It wouldn’t be until the 1980s that Dido’s identity would become relinked to the painting.

Another major controversy was around the authorship of the painting. For over a century it was attributed to the German painter Johan Zoffany, who is portrayed briefly in Belle by veteran Scottish character actor David Gant (who I’d note contributed a vocal performance to my favourite video game Dark Souls). However Zoffany’s involvement was pretty definitively debunked, creating a mystery over which artist really painted it. There’s an episode of the BBC documentary series Fake or Fortune? which features Amma Asante that set out to get to the bottom of it. The program gathered enough stylistic and forensic evidence to conclude that it was in fact painted by the Scottish portraitist David Martin (who is probably best known for his painting of Benjamin Franklin) and this attribution is now widely accepted as correct.

Dido’s accessories, particularly her head wrap or turban with an ostrich feather she was painted with have also been a subject of some debate. Some interpret it as a deliberate attempt by the artist to highlight Dido’s ethnicity and “exoticism” in a way deemed to be demeaning, or even to signify her as servant- like. However there are some details that contradict this, like for instance that Dido is painted with a plaid shawl, which Paula Byrne points out in her book Belle is certainly a hint at Dido’s Scottish heritage. I’ve heard it suggested by Asante that it was entirely possible Dido would have worn something similar to the turban as perhaps a way to approach a head of hair for which care may have been a bit of a mystery to the household Dido was raised in. Other European paintings of Black women from around this time often feature similar headwear.

Portrait of A Young Woman (late 18th century) formerly attributed to Jean-Étienne Liotard.

In a Youtube video by Crow’s Eye Productions (who specialize in historical costuming), four other paintings by David Martin painting appear to depict the very same textile fabric that was used in Dido’s head-wrap, so it was likely in his possession for the purpose of referencing or costuming. It’s impossible to say for certain whether it was an embellishment on the part of the artist or not, or to what degree Dido may have had in selecting her own outfit for the painting, so it’s all just guesswork when it comes to attributing agency and intent to these things. I don’t know for sure, but I’d like to imagine that Dido could express her identity in ways that did make her stand out in positive ways, and perhaps this detail of the painting is alluding to that. I think of how even her name was likely given as a conscious way to evoke that her background was both African and noble, alluding to the (possibly purely legendary) Carthaginian Queen famously featured in Virgil’s The Aeneid. So, it’s not as if her heritage was a secret, and I’m most tempted to view it from that perspective. Of course there was also a trend in orientalist costuming (not to open a whole other can of worms) related to masquerade balls, and it wasn’t unusual to see portraits of white women from around that time wearing turbans, so it may have been an attempt to make Dido appear social and trendy more than anything.

A portrait of Jean Home of Wedderburn by David Martin.

I should add after all of that that the film’s facsimile of the painting omits the vexatious turban and ostrich feather altogether.

Personally I suspect the artist did want to visually distinguish Dido from Elizabeth, while still retaining those underlying similarities which I think make it such a captivating painting. It makes me think of how different people can be from one another while also being closely connected. Still, all of this raises further questions of the role of the artist in all of this. Even though the double portrait is at the heart of Belle, the artist himself is nearly absent from the film (likely due to the aforementioned authorship mystery), so I look again to Mike Leigh...

SEASCAPE

I’ve mentioned a couple Mike Leigh films already, and in many ways his filmmaking comes like the antithesis to the sort of costume dramas I began this piece discussing. One reason for that is because Leigh’s artistry is often concerned with people whose lives are out of step with larger social narratives. It becomes all the more relevant to this article when Leigh’s subject is rooted in history. He’s made four period films, but the one that best compliments Belle and helps further explore this subject is Mr. Turner, the 2014 biopic about the painter, J.M.W. Turner, who is played brilliantly by long-time Leigh collaborator, Timothy Spall. The Turner of the film is as contradictory as the sea; both saturnine and turbulent. He can be genuinely charming and incredibly abrasive. Sometimes even at the same time, like in one scene when he sings Henry Purcell’s Dido’s Lament, in a manner that is both uncomfortably awful while also being moving for how raw and heartfelt it is. Turner’s life is a perfect fit for Leigh since it’s so imperfect , and as an artist Turner could be just as drawn to the incongruous as Leigh.

While slavery is not obviously at the forefront of Mr. Turner, it still plays an implicit role in the film, and Britain’s history of slavery isn’t shied away from. Early in the film there’s a scene between Mr. Turner, Mrs. Booth (the woman who would eventually become Turner’s girlfriend) and Mr. Booth. Turner asks Mr. Booth if he was a man of the sea...

MR BOOTH: Ship’s carpenter.

TURNER: Carpenter? Noble craft. What did you ply? Whalers? Spicers? Traders?

MR. BOOTH: Slavers. For my sins.

MRS. BOOTH: He don’t like to talk about it, though.

MR. BOOTH: Africa, Zanzibar, the Indies. Such terrible sufferings I did see. Treated like animals, they was. Worse than.

TURNER: The howling sound of sorrow.

MR. BOOTH: Yes. Changed my life, it did.

MRS. BOOTH: It did there.

MR. BOOTH: Led me back to chapel.

TURNER: Humans.

MRS BOOTH: Humans can be dreadful cruel. I watch them boys down there in the sands whipping them poor donkeys. Mind you, you’re better off being a donkey than them wretched souls on the slave ships.

It’s a brief scene that touches on the cruel history of British slavery, and also why Turner as an artist would have been motivated (perhaps even felt beholden) to paint a historical scene that examined that legacy.

Turner would go on to paint the most stunning and haunting artistic representation of the The Zong Massacre. The Zong Massacre was already a historic event by the time Turner would paint it, but for his time it was near history. While the painting was created after slavery was officially outlawed within Britain (though there are examples of it continuing in more semantically ambiguous capacities), there were still plenty of men around who had made their fortunes through slavery, and the abolition of slavery remained a hot issue for many nations. Turner’s The Slave Ship was actually first shown while the Amistad case was working its way through the legal system of the United States. The Amistad case was also directly connected to the slave ship Tecora which parallels the Zong in its murdered-by-drowning of a number of the slaves it carried, which was dramatized in the Steven Spielberg film, Amistad (1997).

The Slave Ship (Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying,

Typhoon Coming On) (1840) by J.M.W. Turner.

Unsurprisingly, Turner’s confrontational painting was regarded as tendentious during its time, and didn’t initially sell when unveiled. It represented not only a specific horrific event in the nation’s history, but also a legacy of slavery that most in power in Britain had benefited from and would rather the public forget about as quickly as possible.

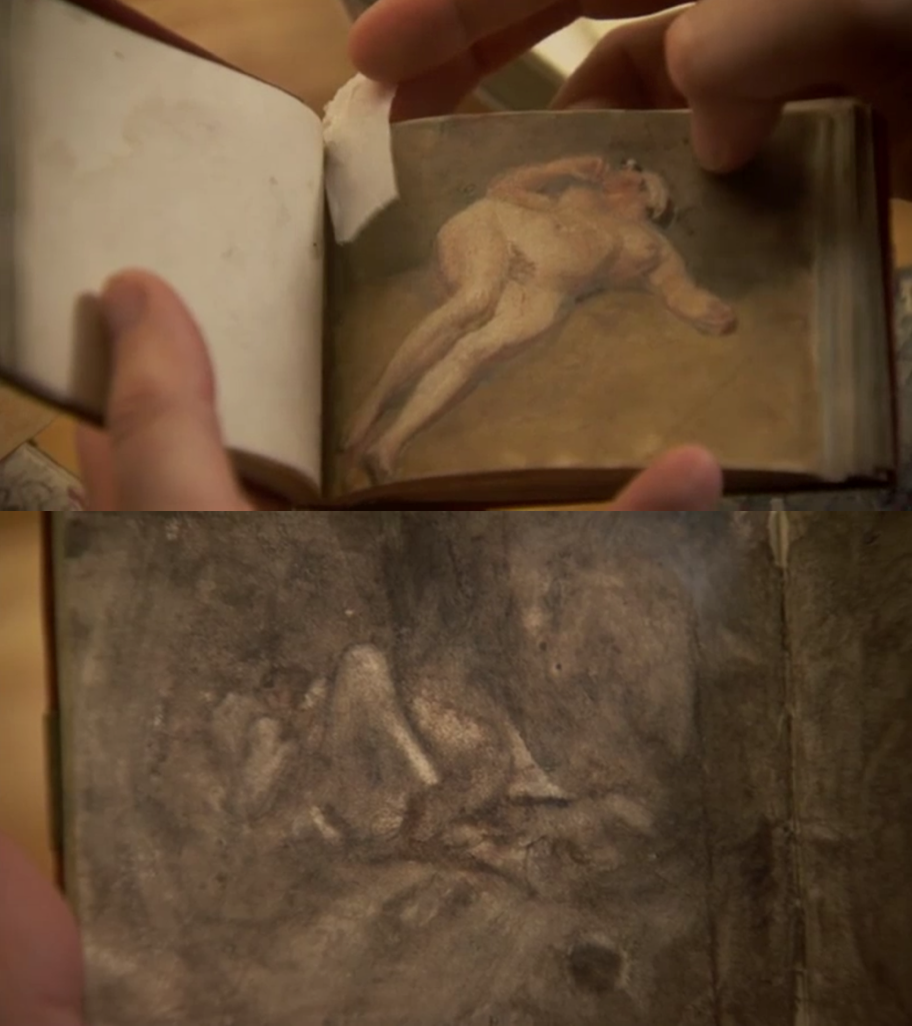

However The Slave Ship would eventually catch the eye of John Ruskin, the leisure-class art critic who convinces his father to purchase it for him. Ruskin would be one of the biggest critical advocates of Turner; a real Turner-booster at a time when the artist’s work was ever-increasingly controversial (as his style developed there would even be accusations that Turner had lost his eyesight or his mind). Ruskin’s association with Turner should hardly be regarded as entirely positive though, not the least of which for actually destroying many works by Turner, with the nudes being the main victim of Ruskin’s particularly Victorian prudishness. There’s a scene in the film in which Turner is shown going to brothel to have a prostitute model for him to sketch such a nude. A handful of those nudes have even survived in sketchbooks, and were showcased in another episode of Fake of Fortune? titled “Turner: A Miscarriage of Justice.”

You can see a very repressed John Ruskin portrayed by Greg Wise in Effie Gray (2014), the biopic about the young woman who had the misfortune of being caught up in a sexless and controlling marriage with him, until she could have it annulled (at a time when divorce was near impossible) on the grounds of their marriage never being consummated, so she could go on to marry the painter John Everett Millais.

The Slave Ship painting is represented in two scenes in Mr. Turner. In the first scene, Ruskin (played with pitch-perfect man-child irritability by Joshua McGuire) convinces his father to buy the painting for him. He comments on The Slave Ship, “I am struck by the column of bright white placed precisely off centre here, applied over the darkened background impasto contrasting with the scarlet and ochre hues in the upper left corner, which in turn contrasts with the presence of God, revealing to us that hope exists even in the most turbulent and illimitable of deaths.”

Timothy Spall as Turner’s own analysis of the painting in the scene comes across as simultaneously much more blunt but far more acute, stating matter-of- factly “Typhus epidemic amongst the cargo, slaves. Die on board, no insurance. Sling 'em in the drink, drowned dead... cash.” It’s a more conversational echo of a supposedly unfinished (it sounds finished to me, but what do I know) poem that the real Turner wrote and paired with the painting when it was first exhibited:

Aloft all hands, strike the top-masts and belay;

Yon angry setting sun and fierce-edged clouds

Declare the Typhon's coming.

Before it sweeps your decks, throw overboard

The dead and dying - ne'er heed their chains

Hope, Hope, fallacious Hope!

Where is thy market now?

The second scene to include The Slave Ship has the painting on the wall near the entrance of Ruskin’s home, seen when Turner is invited over for a salon where he has to endure the praise of Ruskin. It seems to me that within the confines of the film, quietly tragic how a painting with such a powerful perspective on history that would be of great value to the public, would be tucked away in the home of one high society man who treats it like a decoration. It’s practically entombed, which seems to be deliberate as the line “as though the house is built around” is proudly spoken while pointing out the painting. I’m reminded of an infomercial where Vincent Price pitches the art collection to be sold at Sears, saying “... and I hope that over the years you all will come to see art, as I see it, as no more than the ultimate in home furnishings, and I hope that over the same years, your customers and you will come to see art as the furniture of the eye...” There’s no access to the art-as-conduit-to-the-past that I mentioned earlier. How is it possible for art as challenging as this to challenge anything when it’s in the hands of people who are only interested in maintaining the status quo? I think it subtly underscores a deep dilemma Turner is faced with in the film; who is his art for? Is it only for the wealthy and powerful, or is it for everyone? I think this brief moment in the film highlights that the access to artwork is as important as what’s represented in it.

In the salon scene that follows, Ruskin addresses Turner and a handful of his artist peers. Bringing up the subject of seascapes he states, “Alas, I find myself harbouring a perhaps rather controversial opinion regarding the long- deceased Claude...” speaking about the great 17th century French painter Claude Lorrain, elaborating, “I must confess that I find his rendering of the sea rather insipid, dull, and uninspiring.”

Turner defends the artist, saying “Claude was a man of his time.”

Ruskin responds, “My point exactly, Mr. Turner, but that time is now long past. When I experience a modern masterpiece such as yours, I am struck by the clarity with which you have captured the moment. Take for example, your ‘Slave Ship: Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying - Typhoon Coming On,’ by which I have the good fortune to be greeted every morning on my way in to my meagre breakfast. The impact of the foaming brine incarnadine consuming those unfortunate Negro slaves never ceases to quicken the beat of my heart. Yet, when I gaze upon a work of Claude I find myself enduring nothing more than a mere collection of precise brushstrokes, which instil in me no sense of awe whatsoever, let alone the sea.” I think of how the wrong sort of praise can sting worse than harsh criticism. Yes, Claude Lorrain was a man of his time, and so was J.M.W. Turner, and so are we all of our time, but I believe art has the potential to exist beyond time, and connect us to both the past and the future. Often it’s the most incongruous art that is the most enduring. Critical trends are fickle and unforgiving, and elitist critical gatekeepers like Ruskin are typically poor appraisers of the timelessness of art.

I think Turner’s well known for the technological change reflected in his art, as in his famous paintings The Fighting Temeraire (1838) and Rain, Steam and Speed (1844), but it’s worth being aware of the less pictorially obvious social change during his time. It’s also notable how much of Turner’s artwork was focused on historical scenes and moments; everything from ancient history like in Snow Storm: Hannibal and his Army Crossing the Alps (1812) to history experienced during his lifetime like in his painting of the exiled Napoleon, War. The Exile and the Rock Limpet (1842). I imagine Turner must have been aware of what his own place in history might be. I think of how typically “of their time” is used to excuse (or try to at least) any culpability in the socially acceptable wrongdoings of yesterday. In that sense, Turner as a character in Mr. Turner is someone who is aware of his place in the shifting of time. Much of his art wasn’t widely appreciated during his lifetime, especially as his style evolved to become increasingly formless.

There are a few scenes in Mr. Turner which reflect the criticism and distaste for his art. One has a young Queen Victoria herself whispering to her hubby in German about how hideous she finds a Turner painting to be. Another has Turner attend a satirical play performed in a music hall. In the play jam tarts are smashed into a canvas and then put up for sale as a Turner painting. Then in the play, an actor (played by Leigh regular Sam Kelly) playing an upper-class man is shown buying the jam tart painting and singing:

Ye common throng and hoi polloi,

I am a rich and cultured boy.

My wealth derives from tricking knaves,

and selling coffee, tea and slaves.

My house is full of things of beauty

- paintings, sculpture and other booty.

Turner leaves the play disturbed, and is left to reflect on if his paintings are to be more than the ultimate in home furnishings for the upper class, the sort of people who built their wealth on that horrific legacy of slavery, or if there’re to be something else.

The story thread of moral dilemma of an artist, culminates in Mr. Turner in a scene late in the film, based in fact, where wealthy pen-manufacturer Joseph Gillott makes an offer to purchase all of the aging painter’s work for one hundred thousand pounds, a veritable fortune (as Mike Leigh says in the audio commentary, “a lot of bread”), especially for an artist. Turner declines because he has decided to bequeath his remaining body of work to the British nation, so that they would be available for the public to see rather than be stashed away in private collections. This was at a time when there were no public art galleries in Britain. Maybe it’s the idealist in me, but I’m moved by Turner’s desire to leave his artistic legacy in the hands of the public, to give his art to the public for all time. He gave his art to the future.11

CODA

In many ways Belle and Mr. Turner are very different films, but I find it compelling how both films seem to rotate around the history of the Zong massacre and all that it represents, and how together both films highlight the intricately and interconnected relationship between art, subject, artists, society and their relationship with time. Maybe it’s redundant to point out that they are interconnected, but getting into the minutia of it all can reveal insights into the effects of issues like representation and access to art. These films make me consider the necessity for art to reflect the anomalous or marginalized or suppressed, and how that means swimming against the tides of grander societal narratives. The sort of people who fall through the cracks of overarching narratives of history are exactly who I think films and art should strive to depict and be seen without restriction. Art shapes who we are and how we see the world, and often the art that goes against what people with any say wish to see is what’s needed to cut through the (mis)shaping of our past, and see that what might be considered the most genteel and simple of times are built on top of cruel and tumultuous foundations.

It would be necessary to have art that could be affixed with, “though the heavens may fall.”

~ AUGUST 30, 2021 ~

1 I’m talking specifically about costume dramas, but that’s not to say this phenomenon is only regulated to period films. For example, recently I watched a certain major release superhero film with my girlfriend, and I noted that she took issue with the superhero being given a Black best friend character whose only purpose in the film seemed to be to have someone to say aloud to the audience how cool and capable the superhero was. I’m also reminded of actor John Bodega expressing dissatisfaction with the gradual marginalization of his character over the course of the Disney Star Wars sequels.

2 I’m reminded of a joke from the historical comedy series Blackadder. In Blackadder Goes Forth, the season set during WWI, Rowan Atkinson’s character accuses another British captain of being a German spy. The captain assures that he is “as British as Queen Victoria.” Atkinson’s Captain Blackadder retorts, “So your father’s German, you’re half German, and you married a German?”

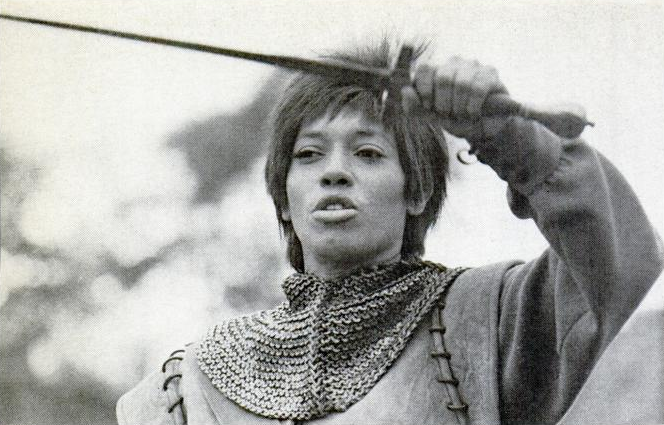

3 I’d kill to be able to go back in time and see the late, great Diana Sands as Joan or Arc in the 1967 production of George Bernard Shaw’s “Saint Joan.”

4 For a more international perspective on many of the issues discussed here, I’d highly recommend reading Natalie Zemon Davis’ book Slaves on Screen: Film and Historical Vision, wherein Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus, Gillo Pontecorvo’s Burn!, Steven Spielberg’s Amistad, and Jonathan Damme’s Beloved are discussed.

5 I say all of this as someone who is considered white, though a century ago wouldn’t have necessarily been the case (with, for example the quote by American sociologist Edward Alsworth Ross, “A slav can live in dirt that would kill a white man,” in mind) shows how nebulous, messy, and socially constructed much of this topic can be... I’m not trying to speak authoritatively about this subject, but as someone interested in art, history, and cinema, I hope I can examine this subject in a respectful and considerate manner and see where it takes this particular piece of writing. These concepts are wide open for critique and deconstruction, and there’s obviously much more to dissect with such a topic than I can discuss responsibly in an article of reasonable brevity, but I’m trying to have one piece of one part of a much larger conversation.

6 Belle kicked off an unofficial trilogy followed by A United Kingdom and Where Hands Touch, wherein Amma Asante used love stories as a framework to interrogate the intersection of ethnicity, femininity, and class through history. While Belle remains my favourite of the three, I think Where Hands Touch in particular was unfairly critically maligned for delivering in 2018 a nuanced exploration of the complexities created by the corrosive effects of Nazism on German identity and the romanticization of Nazism in German society during World War II, at a point in time when I think many critics were seeking to praise films that had a more overt and simplistic anti-fascist themes. It was perhaps just bad timing to release a film about a biracial German girl falling in love with a Hitler Youth and feeling that she is a part of a society that is increasingly and violently alienating towards her, when really most critics were looking for films where unambiguous good guys punch Nazis in the face. Asante had originally tried to make Where Hands Touch prior to making Belle, but that particular iteration of the project didn’t come together. It was however in the casting for that attempt at making Where Hands Touch that Asante was introduced to Gugu Mbatha-Raw who would not star in that film, but who would play Dido in Belle.

7Again, not to imply that this issue is relegated to the past, just that it’s rooted in history. For example, look at the interview of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle by Oprah Winfrey in March of 2021, wherein they related that there were concerns on the part of the Royal Family about how dark the skin of their child would be. Of course, these prejudicial notions of class and race are still around.

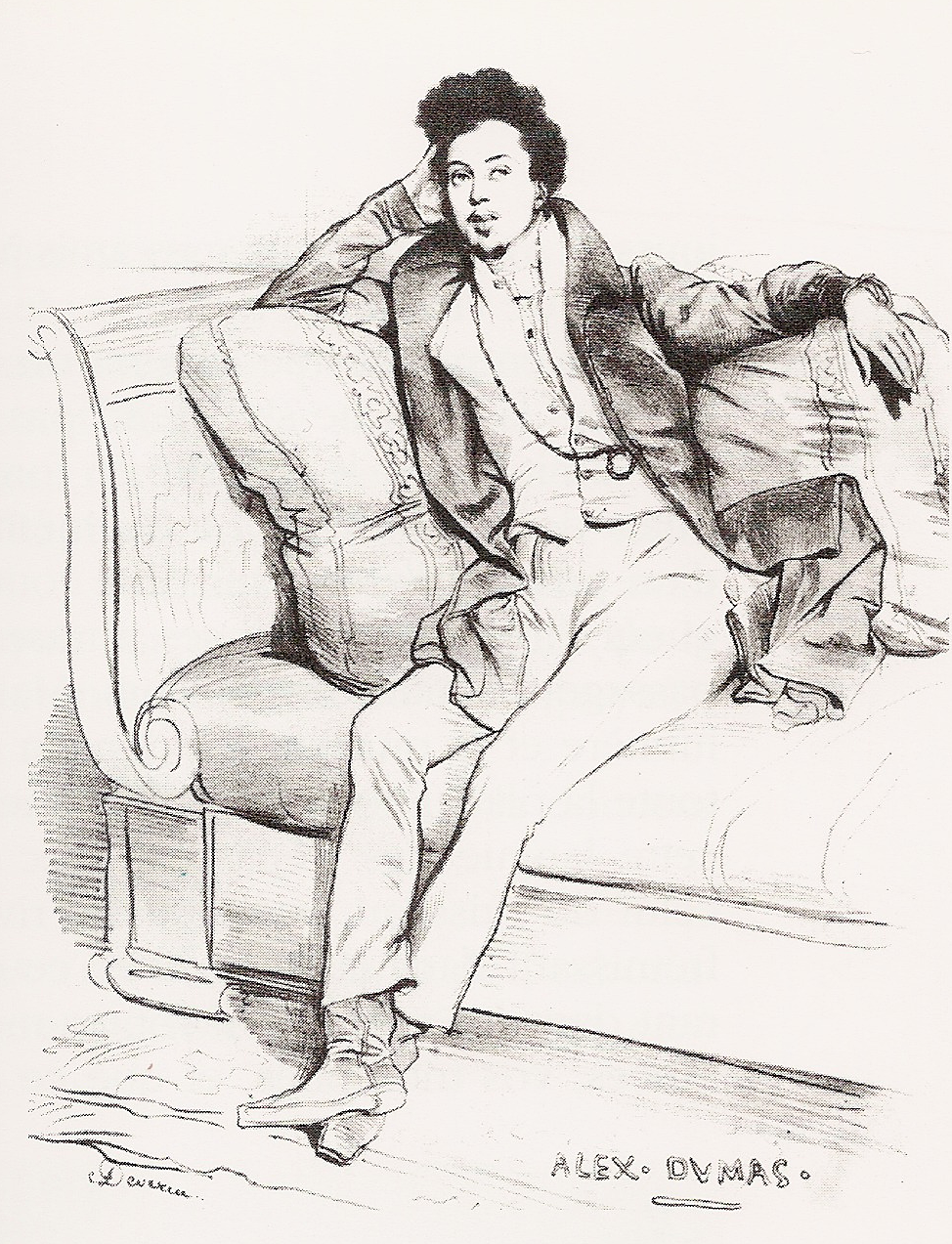

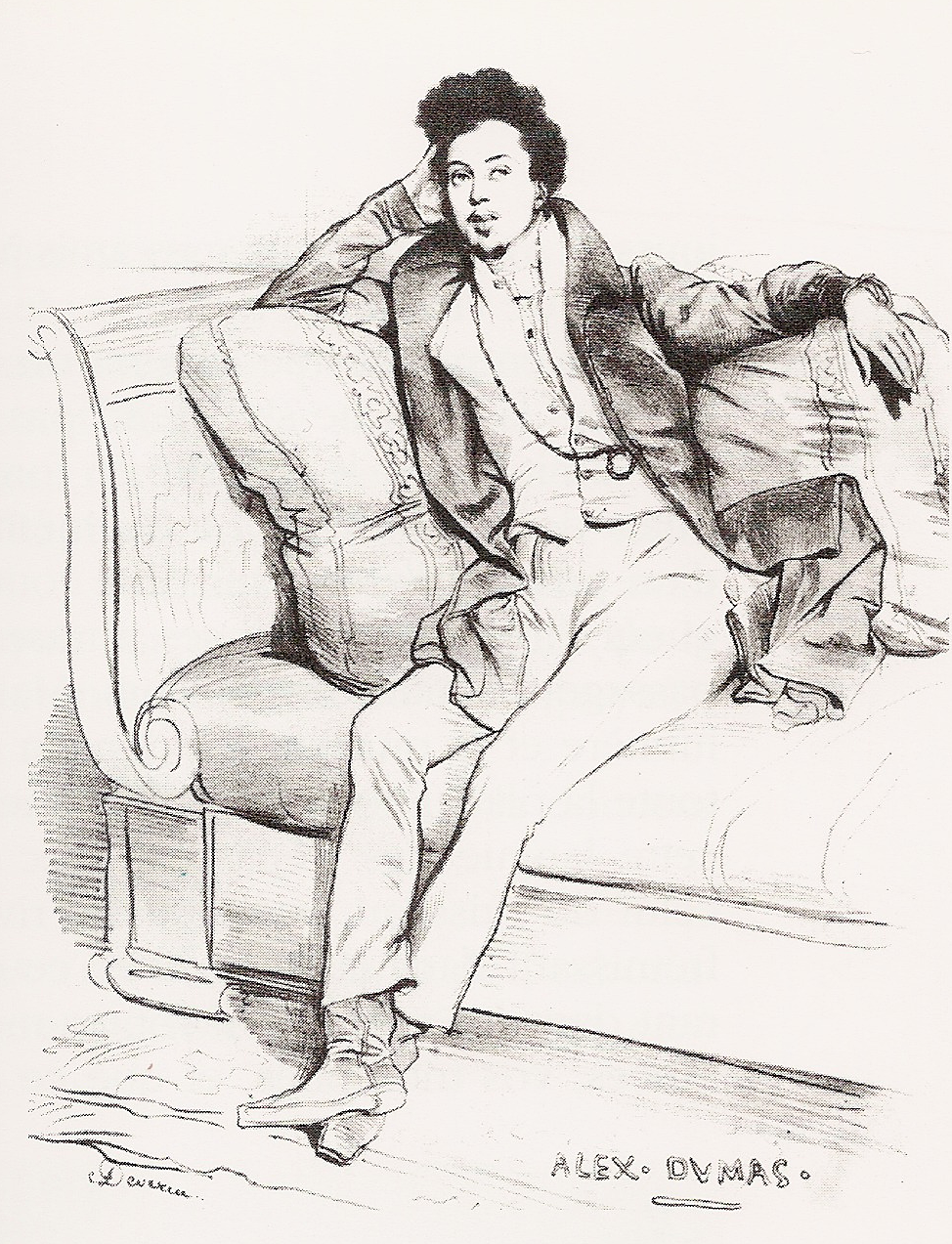

8 Even when the life of such a historical figure makes it to the big screen, like for instance Alexandre Dumas, who was of mixed heritage, he’s played by someone like Gérard Depardieu as in the biopic L’autre Dumas (2010). If anyone, I think young Dumas was pretty close to a dead ringer for the musician Prince, but I digress.

9Just in case there was any doubt about me being genuinely into these costume dramas, here’s a picture of me with the dress worn by Florence Pugh in Lady Macbeth:

10 It was in 1807 when Britain’s involvement in the enslavement and trading of people would officially be ended in an act signed into law by King George III. The abolition of ownership of slaves in the British empire wouldn’t be until 1833, and even then an exception was given to territories owned by the East India Company. It could be said too, that slavery continued in a less legally official capacity via a dominant colonial culture for long after.

11I was lucky enough to see a number of Turner’s paintings in person, when they were lent out to the Art Gallery of Ontario for an exhibition in 2015. I’m not saying this to brag, but because of how astonishing and powerful those works of art were. I think of what a loss it would have been if most of them had been stashed away in private collections, scattered and lost over time. I’m heartbroken to hear today about certain public art galleries like The Brooklyn Museum or The Newark Museum of Art selling off some of their paintings. I think it’s a travesty, really.