THE POINT OF DYIN':

the cinema of charles bronson

~ by john b. cribbs ~

Starting in 1969, Charles Bronson became the angel of death of action cinema. The characters he played in the latter half of his career had "something to do with death," as his mysterious gunman Harmonica is described in Leone's Once Upon a Time in the West. It was that very "something" that held a morbid curiosity even for those he hunted, like West's lifelong sinner Frank, who grudgingly accepts his ultimate showdown with Harmonica by uttering the self-assurance, "The future don't matter to us. Nothing matters now - not the land, not the money, not the woman. I came here to see you. 'Cause I know that now, you'll tell me what you're after." To which Harmonica responds: "...Only at the point of dyin'." A beautiful double meaning: we only learn the point of dying... at the actual point of dying. And for countless creeps and evildoers, Bronson was the grim messenger.

In this series, we'll be writing about movies from Bronson's post-West filmography. Although his earlier work as an essential member of ensemble action epics like The Great Escape, The Magnificent Seven and The Dirty Dozen is indeed significant and worthy of lengthy evaluation, I'm more interested in the last leg of his career when he was doing interesting work for directors such as Michael Winner and J. Lee Thompson. Like leather or scotch, Bronson got better with age, so while his "solo" work may not be as good as the group adventures from the 60's, what the action icon came to symbolize - a weatherbeaten grim reaper - is one withered grape that is ripe for interpretation.

{THE POINT OF DYIN' index}

THE MECHANIC

michael winner, 1972.

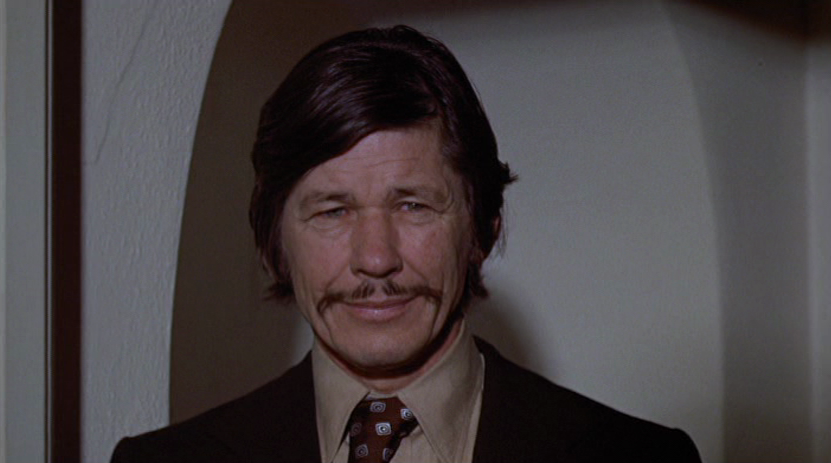

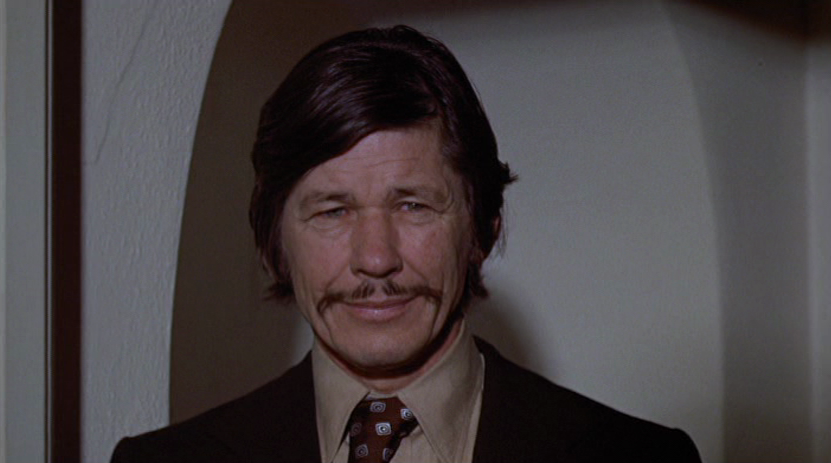

The Mechanic opens in a vacuum, bleached void filling every inch of the frame until Charles Bronson rises into the shot, his dark aura at once corrupting the unblemished background and becoming everything we know. For the first 15 minutes of screentime we'll find Bronson at his most incorporeal, moving among the people of the City of Angels unperceived, watching over their bustling activity from above. His narrow eyes are specifically focused on a man he intends to kill, a seemingly random individual who spends his day harmlessly brewing himself some tea and sitting down with a book in his undistinguished studio apartment. We're never given any indication as to who this man is or why he'd find himself in the crosshairs of an international criminal organization; all we know is that he's been selected from the pedestrian mass to be spectacularly phased out by an unseen emissary.

Bronson is the apparitional Arthur Bishop, a hitman who doesn't seem to exist outside his own carefully-guarded bubble. Maintaining a hermetic existence in a massive home in the Hollywood Hills, he spends time between hits honing his body and mind through rigorous physical training and appreciation of classical music (mostly Beethoven). He also reads a lot of Sartre and obsessively muses over a full-scale print of Bosch's The Garden of Earthly Delights. Opposite the painting is a mural of his own: a billboard where Bishop pins up photos and details of his latest objective, which he focuses on as intently as the socially engaged nude figures who make up the central panel of Bosch's triptych. The panorama of reveling souls, trapped in a surreal realm between paradise and purgatory, could very well represent the throng of anonymous Los Angelites from which Bishop makes out his mark - a montage of knife-throwing practice is intercut with quick shots of the Garden denizens. There's even a hooded, hellbound fish creature in the painting who's leisurely reading a book, not unlike Bishop's first target just before his apartment blows up.

If the film's inclusion of the famous oil painting lends a heavy religious vibe, it's intentional: Bishop approaches each job with a pious sense of detail, reinforcing his image as a herald tasked by some higher power to allot judgment on the wicked. Witnessing the daily routine of his target from the supreme vantage point of a hotel room across the street, he keeps himself as distanced from the actual killing as possible. Just as his hunted half-Apache from Chato's Land - the actor's first collaboration with Michael Winner, released earlier the same year - was able to covertly monitor the doomed Chato-hunting posse like a foreboding spirit, Bronson's Bishop observes his victim through a high-powered telescope to gauge every aspect of the man's daily life. Winner stops short of having the guy kneel at his bed to pray as Bishop watches from afar, but otherwise what we see of the man's ascetic lifestyle and humble existence form the picture of a monk having his movements scrutinized by a stoic seraph.

Once the unsuspecting subject has left his apartment, Bishop quietly breaks in, sets up a liquid that solidifies into a foam which extinguishes the oven's pilot light, and drops sulfuric acid on a gas pipe that will slowly eat its way through. He replaces tea bags with some kind of sleeping powder (encased in the exact same packaging), then globs a healthy amount of triiodide paste inside one of the many books sitting on the shelf. He withdraws to his perch across the street, where he watches patiently as the man nods off from drinking the drugged tea, allows the gas to fill the apartment and only then (around 3:30 in the morning) ignites an explosion by snipering the hardcover smeared with the volatile goop. Bishop calmly disassembles his rifle while the intense fire from the blast glows behind him, sanctified by its decimation. Back at home, he completes the mission by burning the dead man's file.

Now obviously, there's no reason Bishop couldn't have simply waited for his victim to return home and shot him in the head. Or snipered him from across the street. Or replaced the tea bags with poison, or let the gas finish him off as he slept, or for that matter carried out any number of execution methods while his subject was unconscious. But this dialogue-free 15 minute opening establishes Arthur Bishop and his personal doctine: Once you understand how a person lives, you can make them die.

Secluded in his posh sanctum, he pores over detailed dossiers on the pattern of his target's behavior, their interests and routines, pragmatically to resolve the best trap to set for them and make the hit seem like a natural accident, but philosophically to engineer a death that really does feel like it was delivered by the equitable hand of fate. A careless bachelor leaves the gas on and blows up in his nondescript apartment. A jittery, out-of-shape Keenan Wynn keels over dead of a heart attack. If the Omen or Final Destination movies showed a spectral figure setting up and setting off the series of sequential events that lead to a character's demise, it might very well look like Arthur Bishop, a mechanic who learns how the machine functions, studies the workings of it and ultimately sets it in motion. The question behind Bishop's hard gaze: How does the way one lives dictate the way he's going to die?

The way Bishop puts it - "Every person has a weakness, and once this weakness is found, the target is easy to kill" - is a bit of an oversimplification. Is the first target's "weakness" really leisurely reading while drinking tea? Doesn't Bishop enjoy doing the exact same thing? It's even possible that, observing the simple life of his tea-brewing mark, Bishop realizes that his own existence is more or less identical: quiet reading, limited socializing, hiding from the world - is Bishop just waiting until some unseen entity decides to blow him up? And when it happens, will his death be the correct one?

Because what's missing from the calculated mechanism of Bishop's particular wheels of retribution is the judgment: do the people he eliminates deserve to die? The opening hit is ambiguous, a stranger eliminated based on orders from on high, but his second mark is Bishop's pal and syndicate hot shot "Big Harry" McKenna. Harry, who's known Bishop since he was a kid, is the mechanic's only authentic human connection, their visits the only time Martin drops his guard and resembles an actual person. Yet when a new dossier arrives with Harry's picture inside it, Bishop appears almost gleeful setting to the task. It's evident that he likes Harry enough to not want him to die, but whether his buddy has it coming or not is irrelevant - Harry's demise has been initiated, Bishop is the agent to see the operation through to its end. That he personally knows his mark and his mark's routines makes it easier: Bishop will literally have Harry run to him, to his own termination, using what he knows of Harry's insecurities to drive him to his death. There's nothing sadistic about it, Bishop has just put the pieces into place so well that his targets can't see their doom when it's right in front of them, will in fact rush towards it without hesitation (and Harry even knows Bishop is an assassin!)

"Money is paid, but that's not the motive. It has to do with standing outside of it all, on your own," Bishop relates. His boy Sartre held that the feeling of shame proved solipsism to be false, but Bishop has clearly removed shame or conscience from the equation. His separation from the world allows him to perfect his role as an invisible watcher (even moreso than Wim Wenders's angels looking over Berlin - kids can see those guys) and observe the human flow as closely as if he were observing Bosch's microcosm. While Winner may be suggesting a divinity on Bishop's part by framing Bronson in the foreground like a giant looming over a model ship, the real godhead is the guy who pays the money: Frank Dekova as a crime boss credited as "The Man." In the middle of the film, The Man summons Bishop to his opulent home, which requires a journey by sea plane over the ocean to an island and a chauffeured car ride to the isolated location. The Man works on a painting as he speaks with Bishop, the visual connection being that if Bishop refers to a giant artwork as a guide to the souls whose lives are his to take, this is the guy who actually does the painting. If that seems like a stretch, take a look at how close The Man's portrait of his pet cheetah comes to the giant cat depicted by Bosch:

So while he's going about these jobs with full autonomy, the hits are still being dictated by an even more elusive body. Bishop (whose name suggests an agent of a higher power, I'm kind of surprised the film wasn't titled The Bishop) concerns himself with the how and discards the why, content with his image as the solitary hunter surrounded by infinite nothing we saw in the film's opening frame. He doesn't think about the point of dying - what's the point? Is it going to somehow make his job easier, to know why he's doing it? But an anxiety attack suffered during a solo venture to the Marineland of the Pacific which immobilizes as tenaciously as Danny the Tunnel King's claustrophobia suggests Bishop can't function in society when he's not skirting the edges of it as a deadly specter. The pill-popping closer has taken such pains to make himself incorporeal that he's effectively locked himself out from humanity: if you don't know the point of dying, what's the point in living? The truth is that Bishop craves the worldly pleasure of the Garden of Earthly Delights - he doesn't want to be a guardian, he wants to be Adam, even if it means taking the fall.

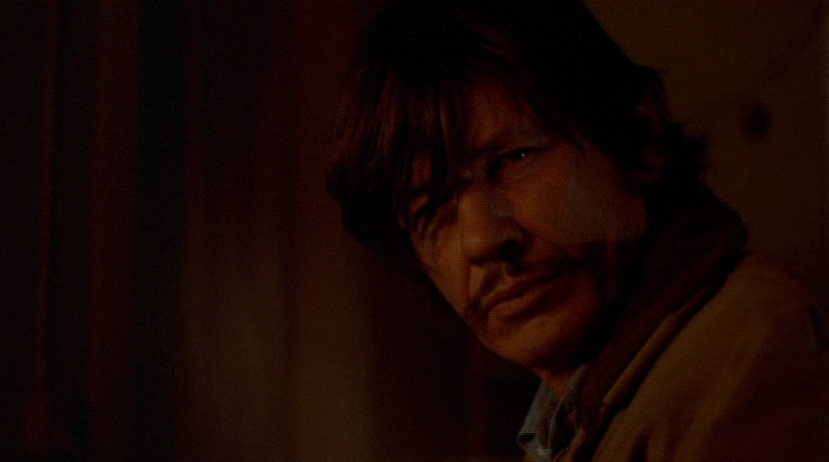

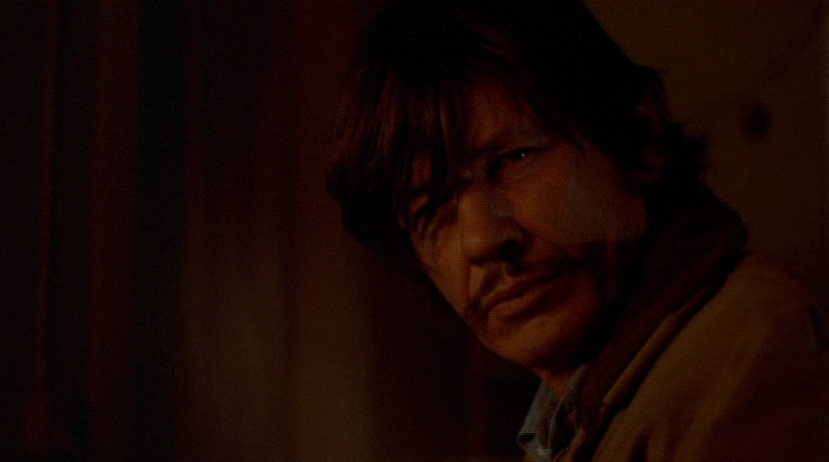

Enter Steve McKenna, played by cherub-faced Jan-Michael Vincent, to serve as Eve to Arthur's Adam. Steve is Big Harry's son; an instant connection is made when it's established that both men had criminal fathers they despise, Steve condemning Harry as a "pusher, pimp, thief, arsonist" while stories of Bishop's "patron saint" of the crime syndicate daddy tossing his son in the river to teach him to swim clearly still effect him. The two bond by observing a young woman who's infatuated with Steve slit her wrists and wait to die in front of a fireplace, the docile composure of its fading flames embodying the same moment of predetermined doom as the cremation of Bishop's first victim. Bishop doesn't lift a finger to help the dying woman of course, maintaining his asomatous mien as they contemplate each other's faces, while an unmoved Steve sadistically mocks the woman's suicide attempt. Perhaps mistaking pathological narcissism for sociopathy, Bishop elects to take Steve under his wing, turning to face the Bosch triptych as he reveals his private vocation to his new recruit. If he's going to get into that Garden, St"eve" is his ticket.

In taking Steve on as a sidekick, Bishop is trying to have the best of both worlds. We've already seen that he pays a prostitute played by Jill Ireland to act out a premise where she pines for him, even reads him love letters (which cost extra!), their scripted emotional grappling giving way to equally spurious love-making. His isolated life makes an actual relationship impossible, so bringing Steve into his world under the role of "assassin in training" allows him to show off his intricate methods while also forming a more authentic human connection (his claims that he needs help with hits because he's "spread thin" aren't very convincing).

We've seen the "cold, lonely hitman makes meaningful link with a regular person" angle in several films - Melville's Le Samourai, Woo's The Killer, Besson's Leon, Mann's Collateral, the first half of Wong's Fallen Angels - but the relationship between Bishop and Steve is better reflected in Michael Winner's follow-up film, Scorpio. Scorpio deals with a pair of government assassins played by Burt Lancaster and Alain Delon (Lancaster had reportedly contacted screenwriter Lewis John Carlino about starring in The Mechanic in the late 60's while Martin Ritt was attached to direct) who work together to take out high-ranking foreign personalities only to have the young student be turned against the master, ultimately leading to the destruction of both. The gap between the two is specified in a scene where Lancaster's Cross meets with Paul Scofield's weathered Russian agent Zharkov:

Zharkov: Have you noticed, Cross, that we are being replaced by young men with bright, stupid faces, a sense of fashion, and a dedication to nothing more than efficiency? Keepers of machines. Pushers of buttons. Hardware men with highly complex toys.

Cross: [raises glass] Here's to dinosaurs.

Although it sounds like Zharkov is describing Bishop, by title designation a "keeper of machines" who prides himself on his efficiency, there's a 20 year age difference between Bronson and Jan-Michael Vincent, so Mechanic shares Scorpio's "young buck supplanting the old model" subtext. Another Winner-Bronson joint, 1973's The Stone Killer, deals directly with Bronson's character being out of touch with the younger generation of long-haired Southern California hippies (viewed briefly in The Mechanic at Steve's post-funeral party) and, like The Mechanic, involves Bronson staring at some iconic art, namely Goya's grotesque Saturn Devouring His Son. One of the interpreted themes of that famous painting is the conflict between the young and the old, and its mythical source - the story of the god Saturn attempting to circumvent the prophecy of his offspring overthrowing him by eating his infant children, only to eventually be usurped by son Jupiter - is relevant to Steve scheming to murder Bishop and become the new mechanic. The ghastly image of a person being consumed whole (by a creature art historians have christened the "Prince of Hell") even pops up in a close-up a scene from Garden of Earthly Delights that Bishop is poring over intently.

Bishop foresees his own supplanting, and may even set his own demise in motion: he reacts to finding a concealed dossier on himself that Steve has secretly prepared like it's a hospital chart disclosing a fatal diagnosis. But rather than acknowledge that young Steve plans to remove him from his grim reaper duties and take over the job, Bishop brings him to see a karate match between Yamoto, an elderly master who Bishop looks at with awe-filled reverence, and Kori, a younger, hairier white punk who's "got some new tricks that are sort of an insult to the old style."

The two watch as Cori fells the seasoned instructor with a sucker punch while bowing, defeating the classic fighter's disciplined style by cheating. Bishop is seeing the traditional, proficient approach to violence be undermined by an inelegant yet effective "new" method but doesn't seem to recognize its relevance to his present situation (at least until the film's final twist, foreshadowed by Yamoto rising to ultimately win the match) even though he refers to Yamoto as "a killer who doesn't kill," tying honorable martial arts violence to his method of wiping out his victims in ways that seem like natural acts.

Because surely enough, Steve's method of execution is far less nuanced and far messier, forcing Bishop to whip out automatic weapons and drive motorbiking baddies off the side of a cliff, the very opposite of a skillfully planned and carried-out killing ("untidy," as Dekova puts it). Bishop can't see that his spectral facade is crumbling because he's too excited at the new possibilities his partnership with Steve has presented. Beyond companionship, what Steve offers is unpredictability. Bishop's ordered modus operandi is suddenly thrown into chaos and there's no longer a forgone conclusion - anything could happen. As a result, the deaths don't appear natural, they are haphazard hits by human beings.

While a chief complaint of contemporary reviews was that Mechanic devolves into more of a straight-up action movie complete with gratuitous (and awesome) motorbike chase, cliff dive, scuba diving, exploding yacht, prolonged ambush, shootout and bulldozer-aided car tipping (even screenwriter Lewis John Carlino dismissed it as a "pseudo James Bond film"), this tonal change reflects the chaotic life Bishop has chosen in recruiting his young charge. Any claim to control has been given up: soon after he starts hanging out with Steve, Bishop takes him up in a plane and gives up the wheel in mid-air, trusting Steve to right the plane - the uncontrolled dive that immediately follows is emblematic of the pandemonium that follows. Bishop has foresaken his role as decider of other people's fates and delivered his own to the erratic forces of chance.

Once it's clear that Dekova's crime boss has it in for Bishop, a deep layer of dread is mixed into Michael Winner's memento mori. When the duo travel to Italy for a high-profile assassination, Winner creates a paranoid feeling of the two being watched as they're watching. Bishop teamed up with Steve to become visible and feel like part of the human race again, and he got it: a vacationing couple even harass him to take their picture! In contrast to Bishop alone, perfect, superhuman, dominating the opening frame of the movie, we see him devouring an ice cream cone as he watches his target descend the sixty-two steps of the Amalfi Cathedral, the church towering above and overwhelming the shot. He also finds that enemies shoot back: as Bishop moves into defense mode facing swarms of armed goons following a double-cross, he's forced to improvise desperately just to survive.

But even this ubiquitous menace is just a smoke screen to the real threat of the feather-haired schemer for whom Bishop has tasted the forbidden fruit. As a consequence of the union between Bishop and Steve, the second half of the film becomes something completely different: a movie about a sociopath with a philosophy who takes under his wing a psychopath with an agenda. Steve, enamored with the lifestyle, the fancy hillside hideaway, the flashy Mustang and other earthly delights, is young and still very much a part of the world, he can't be expected to buy into Bishop's ideology of "standing outside of it all." A walk through a wax museum of genocidal leaders and old-fashioned outlaws Bishop admires for their divine estrangement from the rest of humanity doesn't effect Steve in the slightest - it's still a museum, grandpa! Bishop and his code of killing are as much a relic to Steve as the wax figures, and about as useful. Steve ends up poisoning his mentor with brucine, making it clear that it's not revenge for his father (he didn't even realize Bishop was the one who killed him) but because he has his own ideas about who to eliminate and how:

"They told you who to hit. Kept the whole idea from being what we talked about. You needed a license - their license. I'm going to pick my own mark. Hit when I want. Just like you said: standing outside."

At least the kid was paying attention, but Steve's injection of the judgment element into Bishop's philosophy is too extreme. He intends to utilize what he learned to become a hit man serial killer, one who doesn't need a dossier to identify a target: if he decides someone deserves to die, that's good enough for him! He doesn't care about the way people live, only about the goal of killing them. Bishop was an emissary, Steve intends to be death itself. He's not a heart attack, he's a wildfire. An atom bomb. Not so much a mechanic as a demolitions expert, fashioning himself after Bishop's earlier claim that "Murder is only killing without a license" by concluding that once all authority has been rejected, he's free to ignore the natural order entirely. But he learns too late - that's right, at the point of dying - the cost of trying to avoid it.

Bishop chose flesh and bone over disembodied wraith, but his perception of natural order never faltered. Steve returns to the L.A. safehouse only to find Bishop has rigged the car with a timed explosive and a posthumous farewell note. Steve is burned right out of existence as cleanly as Bishop's first victim and for the same reason. In coveting what Bishop has built over a career of standing outside the lives of regular human beings, Steve slips into the petty, sinful routine of any one of them. He's set himself up to be judged, and when judgment comes it's delivered by the disembodied hand of a cruel avenger; ironically, it's in death that Bishop is able to allot cold retribution to someone who truly has it coming.

The Mechanic was the first movie Bronson shot on American soil in 6 years following his string of career-igniting European co-productions and his first top billing of any film he'd made in the U.S., Chato's Land having been filmed in Spain. These first two collaborations with Winner are firmly set in the "mythical seeker" region of Bronson's filmography a'la the spectral figures he portrays in Once Upon a Time in the West, Rider on the Rain and Violent City, but over the course of The Mechanic you sense Winner deliberately pulling his star out from his supernatural comfort zone. Their next film would be Death Wish, in which Bronson isn't a mysterious assassin, a silent stranger or a vengeance-seeking stalker - he's just a guy, a regular joe whose transformation into the silent, vengeance-seeking assassin is the result of a tragedy that befalls one of the many citizens of a large city. If Mechanic sees Bronson stepping out of his role as otherworldly avenger, Death Wish is him falling back into it the hard way. It's funny to think that a Bronson hero really does want a nice day at the aquarium or to enjoy an ice cream cone in Amalfi or have a normal relationship with a woman who writes him love letters, but that fate always has something else in mind for him. It seems that in order to live, he's just always having to think about how other people die.

~ DECEMBER 4, 2018 ~