SUSAN CABOT

~ by john cribbs ~

December 10, 1986 - Encino, California.

By all accounts, Susan Cabot had a strange life. A Jewish girl raised in eight different foster homes in and around Boston, she eventually made her way to Manhattan. She did some singing in nightclubs and for ads on the radio before landing a spot as an extra in Kiss of Death (only the back of her head made it into the final film). She was signed by Universal and appeared in several supporting roles, but it was three years after she’d given up film acting that Roger Corman came knocking. Over the next three years she appeared in the American International B-movies that became her milestones including The Saga of the Viking Women and Their Voyage to the Waters of the Great Sea Serpent. Around that time she began a relationship with King Hussein of Jordan: he bought her a Rolls Royce but allegedly dumped her after learning she was born with the name Harriet Shapiro. Two husbands and a line of other notable lovers such as Marlon Brando (and Corman) ultimately produced a son. In a cruel twist of fate the boy suffered from dwarfism, a hard blow to the 5'2" actress who’d supposedly struggled to find work due to her modest stature. She quit acting for good in 1960 at the tender age of 33 and after her second divorce the two lived as recluses in their large Encino home, which is where she was found beaten to death on December 10, 1986.

SORORiTY GiRL

roger corman, 1957.

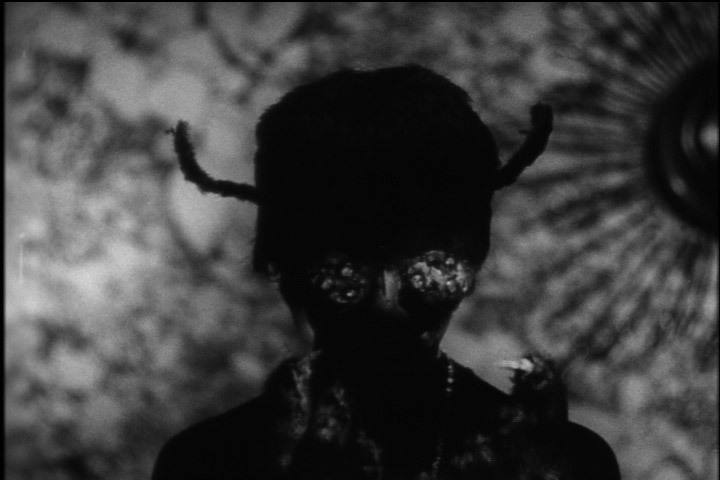

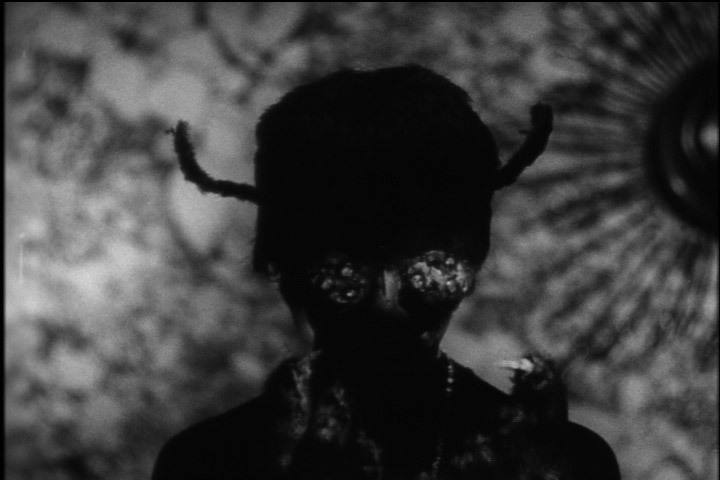

Sorority Girl – the second of six features she'd do with Corman* – opens with an amazing animated title sequence, a low budget combo of Saul Bass and Chuck Jones by the great Bill Martin (he designed five such segments for Corman, three of them for films starring Cabot – after that his credits dry up, whatever happened to him?) Complimented by a fantastic score from Ronald Stein (Corman's Bernard Herrmann), Martin's visuals depict a young woman mutating into some kind of deformed monstrosity with six protruding arms, then gripping the sides of her head in silent gray Munchian agony before fading away into a bleak background of dead trees. This expressionistic representation depicts the inner struggle of Sabra, whose name itself evokes the image of some exploited circus animal. We meet her on her knees, defeated, alone on a beach in a one-piece swimsuit, vulnerable but too weakened to defend herself against the incoming waves. In voice-over she asks herself how she reached such a miserable low, sending us back some weeks earlier to an exclusive sorority somewhere in southern California.

Cabot puts a lot into Sabra: she walks about with a cocky stride and confident smirk set in a cold stare permanently on display. She's got a natural prettiness with a hard edge, speaking to those around her with either a forced politeness bordering on maniacal vacuousness or a sharp, stinging condescension. With short black hair and thin dark eyebrows like a demon Liz Taylor, she's a prim piranha in her perfectly pressed turtlenecks, prowling the dorm hallways on campus looking to practice her particular brand of oily manipulation. The funny thing is that it doesn't work on most people; only awkward, eager-to-please pledge Ellie - who sees in Sabra all the physical and preeminent qualities she lacks - finds herself ironing dresses at all hours and subjecting herself to painful, humiliating exercises at Sabra's whim. Not satisfied with this easy prey, Sabra sets her sights on stealing her popular roommate's boyfriend (the great Dick Miller, playing against type as Mort, the studly owner of a beachside bar). His rejection of her advances sets in motion a revenge scheme involving a pregnant student that leads to tragedy and Sabra's undoing.

Sabra is a paradox: a ruffian without a crowd. In a reversal of the classic structure of nasty girls from the popular group picking on the goodhearted individual, here the clique are the innocent ones and ultimately gang up on the bully. As a senior member of the sorority she feels she has carte blanche to expose her sisters' secrets, claim their boyfriends for her own and casually torture pledges, the latter activity culminating in a good old fashioned spanking with the Greek paddle. Sabra's behavior stems from a paranoia which puts her on guard against fellow sorority members who'd just as soon ignore her. She's like Lili Taylor in I Shot Andy Warhol, acting like she's "in" with the Factory while clearly aware she's the subject of contempt and ridicule from those around her. Sabra believes people see her as an outsider - a cruel rich bitch - and acts the part accordingly. She wants to be accepted but has predetermined that her position at the school only allows her to criticize and abuse those beneath her. She's a self-hating sadist.

Of course someone brimming over with self-hatred didn't just pick it up on their own, that hatred had to be inspired by something. "Darling, I knew you were a rat the day you were born," Sabra's high society mother informs her over dinner. "It's hereditary then," she responds in kind. Corman isn't known for his subtle psychological dissection of characters, but the scenes between Sabra and her mom are scathing. Faced with the woman whose callous cruelty she's based her own character on, Sabra's perverse smile is harder than ever. A later scene when Sabra seeks her mother for solace after realizing she's gone too far only to be summarily chided and sent away is kind of heartbreaking, and only proves to her that her own personal punishment - condemning herself to a life as a monster - is justified.

Cabot does insecurity well. She quivers with self-pity when chastised but gets smug the second she has the upper hand, enjoying the power she has over others. To her blackmail is a logical next step from hazing and verbal abuse - it's all been written into her DNA. The fact that she's destined to be a horrible person is a tragedy. If her height truly was a perceived deterrent to her career, it at least afforded Cabot the skill of making her performance seem bigger. It's only in moments when Sabra has been overwhelmed and beaten down that Cabot's small figure is apparent. Whether or not insecurity over her small stature influenced her portrayal of Sabra is debatable, but she definitely uses it to enhance the performance one way or another.

Amazingly, Corman exercises a remarkable amount of restraint in Sorority Girl. There are numerous opportunities to take it over the top - for the heat to rise and the violence to boil over - but he doesn't go for easy exploitation gimmicks. There's no murder, only melodrama. Not much sex beyond the failed seduction of Mort and the controversial pregnancy which serves the story. The spanking scene and a brief catfight are played up a little, but aren't nearly as excessive as they could have been. It seems that for once Corman was more interested in the script than the sensationalism.

THE WASP WOMAN

roger corman / jack hill, 1959.

The same can't be said for The Wasp Woman. Corman films from the last 50's and early 60’s tend to fall in one of two categories: enjoyable B-thriller/comedies (The Little Shop of Horrors, X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes) and lazy monster movies pieced together with crappy stock footage, derivative of whatever the last big creature feature was (It Conquered the World, Creature from the Haunted Sea). Not that the latter movies didn't have their charm – they all employ inventive low-budget effects and have rightly secured their cult status; I for one love the fact that they exist. But after seeing a genuinely tense exploitation film like Sorority Girl it was tough to get through The Wasp Woman, Corman's attempt to cash in on the success of 20th Century Fox's The Fly from the year before. Following a slow expository forty minutes, the formula throughout the second act is fairly tedious and unremarkable: attack, confusion, attack. Compared to the former film's amazing credit sequence, titles over a generic shot of a quilt of angry wasps didn't help (although Fred Katz's jazzy score is a lot of fun).

All that aside, the movie is actually a perfect companion piece to Sorority Girl**. In both films Cabot plays a character whose insecurity turns her into a monster, although she fits the more classic definition and racks up a higher body count in The Wasp Woman***. She plays cosmetics entrepreneur Janice Starlin, whose face launched the look and line of Starlin Enterprises when she was a fierce vixen of 22. Sixteen years older (hence the heavy glasses and lack of make-up – Cabot even employs some creative face scrunching) Janice is losing the fire she needs to keep her company's executives in check and beauty that drew customers to its ads (I have to admit, I was perplexed as to why they didn't just run ads featuring the older/younger photos of her – it's not like Wendy from Wendy's or Aunt Jemima updated their photos every couple of years). Lucky for her, a shady entomologist has been extracting enzymes from the royal jelly of queen wasps which he claims can reverse the aging process. Although it's still being tested on cats and guinea pigs, Janice steals into the lab and starts injecting more than the prescribed dosage. The serum makes her younger, the company's business skyrockets, the crazy scientist gets a healthy bonus, he marries Janice and they both move to Europe and live happily ever after.

Ok, we all know that's not what happens. Not spoiling too much, I can reveal that one of the previously mentioned characters transforms into a wasp monster with a human female body and the other ends up being killed by the monster. But I won't say which one – you'll have to see for yourself.

Although she's not "aged" very convincingly (just over 30 at the time, Cabot is fixed up with heavy eyebrows and an awkward haircut that’s a mix of Princess Leia and Gary Oldman's "butt-do" from Bram Stoker's Dracula), Janice's frustration over losing her once bankable looks is all over Cabot's fragile features. Like Sabra she's plagued by self-doubt and insecurity, forced to play the bully. In this case it's a corporate shell she has to wear to maintain her command as a woman in the business world - something that's simmered and dimmed with age and has to be regained. After her first transformation the desperation overwhelms her: "How old do I look? TELL ME! How old do I look?!" And as her Sorority Girl maneuvered and manipulated her way into being turned on by her fellow students, labeled inhuman - "something the sea cast out" - her Wasp Woman transforms into a creature that strikes out against every imagined enemy: her competitors, members of the board, her secretary. She meets a stickier end than Sabra, taking a vat of carbolic acid to the face and being hurled out the window. While filming this climatic battle, Cabot inhaled too much of the liquid smoke the effects guy poured on her mask and nearly suffocated. A crew member ripped off the mask (and some skin) just in time. It was the last movie she ever appeared in.

Cabot and Corman created on a small scale what William Castle and Joan Crawford achieved with their collaboration on Straight Jacket: the pairing of a schlock filmmaker offering more interesting roles and former Hollywood actress whose A-quality performance enhanced the material. Unfortunately, the Crawford connection extended to media speculation of a Mommie Dearest-esque relationship with son Timothy Roman. While he and Cabot lived as shut-ins, apparently inseparable, she was said to have forced him to take experimental growth hormones thought to have bad neurological side effects. When police arrived at the scene at 10:30 pm on December 10th, Timothy informed them that "a tall Latino with curly hair, dressed like a Japanese ninja warrior" had attacked the two of them using "ninja methods" and gotten away with $70,000 in cash. Within hours the truth emerged: he had bludgeoned her to death with a weight-lifting bar, possibly while she was asleep. He managed to convince the court that his mother lived a Norma Desmond lifestyle with a Delbert Ward sense of home decor and subjected him to "child abuse" (at the time, he was 22). He received a three-year suspended sentence and, when he got out, moved back into the house where he had murdered his own mother. He now blogs online.

I want to try not to end this one on a downer, so as an added bonus and to better appreciate the earlier, non-Corman career of Susan Cabot, I watched Don Siegel’s 1952 western The Duel at Silver Creek. Siegel's first western – and first color feature – it lacks the down-to-earth grittiness of his later studio B-movies but serves up more than its share of excellent moments. This tale of no-good claim-jumpers hiding out in a town defended by quick-draw Sheriff Lightning (Stephen McNally) and the (sort of) vengeance-seeking Silver Kid (Audie Murphy) kicks into gear right away with a hellacious shoot-out on horseback. A wounded victim of the crooks is brought into town and the female lead offers to help nurse him back to health, only to strangle the poor bastard to death! Sheriff Lightning informs a troublesome dude he's unwanted, and emphasizes it by pushing him through a saloon window! And to top it all off Audie Murphy, wearing one of the best-looking jackets in cinema history, takes decisive action when he learns his sweetheart's in the bad guys' clutches by rushing into the fray of a climatic gun battle and launching himself through the front window Mr. Majestyk-style! And keeping his hair perfectly coifed in the background is Johnny Sombrero, who has one of the best character names in the annals of western film (it's so awesome Cabot and McNally repeat the full name half a dozen times in their first dialogue together).

I want to try not to end this one on a downer, so as an added bonus and to better appreciate the earlier, non-Corman career of Susan Cabot, I watched Don Siegel’s 1952 western The Duel at Silver Creek. Siegel's first western – and first color feature – it lacks the down-to-earth grittiness of his later studio B-movies but serves up more than its share of excellent moments. This tale of no-good claim-jumpers hiding out in a town defended by quick-draw Sheriff Lightning (Stephen McNally) and the (sort of) vengeance-seeking Silver Kid (Audie Murphy) kicks into gear right away with a hellacious shoot-out on horseback. A wounded victim of the crooks is brought into town and the female lead offers to help nurse him back to health, only to strangle the poor bastard to death! Sheriff Lightning informs a troublesome dude he's unwanted, and emphasizes it by pushing him through a saloon window! And to top it all off Audie Murphy, wearing one of the best-looking jackets in cinema history, takes decisive action when he learns his sweetheart's in the bad guys' clutches by rushing into the fray of a climatic gun battle and launching himself through the front window Mr. Majestyk-style! And keeping his hair perfectly coifed in the background is Johnny Sombrero, who has one of the best character names in the annals of western film (it's so awesome Cabot and McNally repeat the full name half a dozen times in their first dialogue together).

You know a movie's worth an hour and 17 minutes of your time if you can write an entire paragraph about it without even mentioning that Lee Marvin's in there too. A young Lee Marvin - with a mustache!

Cabot is the gal Murphy takes the suicide dive for, and she's a spitfire - a plucky tomboy with a shotgun. She doesn't fall under Johnny Sombrero's spell, and even takes aim at him during a tense stand-off with the sheriff ("I got a load of buckshot waiting for you, Johnny!") Initially she's not having any of Murphy's charms either: he has to pull off a daredevil stunt to sweep her off her feet. There's a genuinely sweet moment at the end where the Silver Kid and "Dusty" Fargo share their real names with each other, and Luke and Jane walk off into the figurative sunset together. Seeing her as a supporting character in this mileau, the epic studio B-western as opposed to the streamlined Corman B-horror or exploitation picture, you can't help but notice how she almost disappears in it. None of the insecurity or psychological damage of the Corman films follows her Dusty into the wild west - weird to think that a performance in The Wasp Woman would come across as deeper and more interesting than one in what most people would consider a more legitimate film. In Duel her tiny size is unmistakable: the famously diminutive Audie Murphy towers over her by a head (even if he was wearing lifts, that's pretty remarkable). Although she played a gunslinging girl-of-action in Siegel's film, it was as a villain and a bug in Corman's small movies that made her really seem tall.

Cabot is the gal Murphy takes the suicide dive for, and she's a spitfire - a plucky tomboy with a shotgun. She doesn't fall under Johnny Sombrero's spell, and even takes aim at him during a tense stand-off with the sheriff ("I got a load of buckshot waiting for you, Johnny!") Initially she's not having any of Murphy's charms either: he has to pull off a daredevil stunt to sweep her off her feet. There's a genuinely sweet moment at the end where the Silver Kid and "Dusty" Fargo share their real names with each other, and Luke and Jane walk off into the figurative sunset together. Seeing her as a supporting character in this mileau, the epic studio B-western as opposed to the streamlined Corman B-horror or exploitation picture, you can't help but notice how she almost disappears in it. None of the insecurity or psychological damage of the Corman films follows her Dusty into the wild west - weird to think that a performance in The Wasp Woman would come across as deeper and more interesting than one in what most people would consider a more legitimate film. In Duel her tiny size is unmistakable: the famously diminutive Audie Murphy towers over her by a head (even if he was wearing lifts, that's pretty remarkable). Although she played a gunslinging girl-of-action in Siegel's film, it was as a villain and a bug in Corman's small movies that made her really seem tall.

One final thing...In reviewing the work of Susan Cabot I was captivated by another regular AIP actress who died tragically young: Barboura Morris (nee O'Neill), known as the "mystery woman of low-budget pictures." She plays Cabot's arch-nemesis in Sorority Girl (the one who yells at her "You're not human - you're something the sea cast out!" in the searing finale) and her loyal secretary/near-victim in Wasp Woman. She was a regular Corman player, most notable as Walter Paisley's reluctant muse in the classic A Bucket of Blood. Little is known about her besides the fact that she was once married to Monte Hellman and died in 1975 at age 43, supposedly of cancer. Cabot once spoke of her in an interview: "Barboura Morris was a lovely actress, a very sweet lady and a nice friend -- but she always seemed very sad to me. I'm sorry she's gone.".****

~ 2009 ~

* Their first collaboration, the melodramatic rocksploition film Carnival Rock, also featured Dick Miller and co-starred Brian Hutton, eventual director of Where Eagles Dare and Kelly’s Heroes. Hutton quit directing in the mid-80s to become a plumber – true story.

** Both films were later remade: Sorority Girl, re-titled Confessions of a Sorority Girl, was redone for TV in 1994 featuring Alyssa Milano as Rita and Brian Bloom as Mort, and Wasp Woman under the same title in 1995 by Mr. Jim Wynorski, with The Coriolis Effect’s own Jennifer Rubin in place of Cabot and Corman serving as executive producer. Wynorski by the way is now credited with directing 79 movies – what have you done lately?

*** Also released as Insect Woman – watch out Imamura!

**** Whoops... guess I did end this on kind of a downer. Sorry.

I want to try not to end this one on a downer, so as an added bonus and to better appreciate the earlier, non-Corman career of Susan Cabot, I watched Don Siegel’s 1952 western The Duel at Silver Creek. Siegel's first western – and first color feature – it lacks the down-to-earth grittiness of his later studio B-movies but serves up more than its share of excellent moments. This tale of no-good claim-jumpers hiding out in a town defended by quick-draw Sheriff Lightning (Stephen McNally) and the (sort of) vengeance-seeking Silver Kid (Audie Murphy) kicks into gear right away with a hellacious shoot-out on horseback. A wounded victim of the crooks is brought into town and the female lead offers to help nurse him back to health, only to strangle the poor bastard to death! Sheriff Lightning informs a troublesome dude he's unwanted, and emphasizes it by pushing him through a saloon window! And to top it all off Audie Murphy, wearing one of the best-looking jackets in cinema history, takes decisive action when he learns his sweetheart's in the bad guys' clutches by rushing into the fray of a climatic gun battle and launching himself through the front window Mr. Majestyk-style! And keeping his hair perfectly coifed in the background is Johnny Sombrero, who has one of the best character names in the annals of western film (it's so awesome Cabot and McNally repeat the full name half a dozen times in their first dialogue together).

I want to try not to end this one on a downer, so as an added bonus and to better appreciate the earlier, non-Corman career of Susan Cabot, I watched Don Siegel’s 1952 western The Duel at Silver Creek. Siegel's first western – and first color feature – it lacks the down-to-earth grittiness of his later studio B-movies but serves up more than its share of excellent moments. This tale of no-good claim-jumpers hiding out in a town defended by quick-draw Sheriff Lightning (Stephen McNally) and the (sort of) vengeance-seeking Silver Kid (Audie Murphy) kicks into gear right away with a hellacious shoot-out on horseback. A wounded victim of the crooks is brought into town and the female lead offers to help nurse him back to health, only to strangle the poor bastard to death! Sheriff Lightning informs a troublesome dude he's unwanted, and emphasizes it by pushing him through a saloon window! And to top it all off Audie Murphy, wearing one of the best-looking jackets in cinema history, takes decisive action when he learns his sweetheart's in the bad guys' clutches by rushing into the fray of a climatic gun battle and launching himself through the front window Mr. Majestyk-style! And keeping his hair perfectly coifed in the background is Johnny Sombrero, who has one of the best character names in the annals of western film (it's so awesome Cabot and McNally repeat the full name half a dozen times in their first dialogue together).  Cabot is the gal Murphy takes the suicide dive for, and she's a spitfire - a plucky tomboy with a shotgun. She doesn't fall under Johnny Sombrero's spell, and even takes aim at him during a tense stand-off with the sheriff ("I got a load of buckshot waiting for you, Johnny!") Initially she's not having any of Murphy's charms either: he has to pull off a daredevil stunt to sweep her off her feet. There's a genuinely sweet moment at the end where the Silver Kid and "Dusty" Fargo share their real names with each other, and Luke and Jane walk off into the figurative sunset together. Seeing her as a supporting character in this mileau, the epic studio B-western as opposed to the streamlined Corman B-horror or exploitation picture, you can't help but notice how she almost disappears in it. None of the insecurity or psychological damage of the Corman films follows her Dusty into the wild west - weird to think that a performance in The Wasp Woman would come across as deeper and more interesting than one in what most people would consider a more legitimate film. In Duel her tiny size is unmistakable: the famously diminutive Audie Murphy towers over her by a head (even if he was wearing lifts, that's pretty remarkable). Although she played a gunslinging girl-of-action in Siegel's film, it was as a villain and a bug in Corman's small movies that made her really seem tall.

Cabot is the gal Murphy takes the suicide dive for, and she's a spitfire - a plucky tomboy with a shotgun. She doesn't fall under Johnny Sombrero's spell, and even takes aim at him during a tense stand-off with the sheriff ("I got a load of buckshot waiting for you, Johnny!") Initially she's not having any of Murphy's charms either: he has to pull off a daredevil stunt to sweep her off her feet. There's a genuinely sweet moment at the end where the Silver Kid and "Dusty" Fargo share their real names with each other, and Luke and Jane walk off into the figurative sunset together. Seeing her as a supporting character in this mileau, the epic studio B-western as opposed to the streamlined Corman B-horror or exploitation picture, you can't help but notice how she almost disappears in it. None of the insecurity or psychological damage of the Corman films follows her Dusty into the wild west - weird to think that a performance in The Wasp Woman would come across as deeper and more interesting than one in what most people would consider a more legitimate film. In Duel her tiny size is unmistakable: the famously diminutive Audie Murphy towers over her by a head (even if he was wearing lifts, that's pretty remarkable). Although she played a gunslinging girl-of-action in Siegel's film, it was as a villain and a bug in Corman's small movies that made her really seem tall.