BETTER THAN

HiTCHCOCK

c.a. funderburg

It’s the sinister little secret of The Pink Smoke that we don’t much care for Alfred “Marnie” Hitchcock. And while we certainly have zilch-o interest in debating the merits of a filmmaker that everyone can agree is “the greatest of all-time and you’d have to be some sort of malcontented and willful iconoclast to disagree,” we are interested in a strange phenomenon: while we don’t adore the man himself, we have a tendency to love Hitchcock knock-offs.

From William Castle’s lazy copy-catting to Francois Truffaut’s loving pastiches, there’s a chance that if a film shamelessly apes the master of suspense, we’re really going to enjoy it. Brian DePalma, Jonathan Demme, Stanely Donen; the list of great filmmakers who tried their hand at a Hitchcockian shtick is extensive and hugely appealing to explore – and honestly, we’ll take either “French Hitchcock” over the real thing any day, whether you consider the mantle to rightfully belong to H.G. Clouzot or Claude Chabrol.

In this series, we’ll look at parodies, assiduous imitators, and off-brand “Hitchcock-like Film Product” in order to dig into just what it is that we love so much about these movies. Sure, you’ll blanche at the suggestion,* but we think these films are Better Than Hitchcock.

MASQUES

claude chabrol, 1987.

“He beats everyone at every game. He’s a monster.”

In my piece on The Bride Wore Black, I began by discussing how I was unsure what made the film a Hitchcock pastiche apart from the fact that critics and Francois Truffaut himself referred to it as such. With his fellow Nouvelle Vague critic-turned-filmmaker’s film Masques, I am 100% comfortable applying the word “homage” if not “patsiche” - maybe only because its litany of “references,” “nods” and “acknowledgements” to Hitchcock are as plain as day and the bar for “homage” is lower than “pastiche.”

I might be drawing a line between the two terms that’s arbitrary, but “pastiche” to me implies a totality, while “homage” can be found in bits and pieces, in fleeting moments and with a certain vagueness on the macro-level. At any rate, on a purely surface level, Chabrol’s film has a much clearer relationship to The Master of Suspense than Truffaut’s, both in terms of concrete references and how it matches up with the critical imagination of Hitchcock - it even features a shot of a doorknob turning slowly!

Chabrol’s relationship to Truffaut vis-a-vis Hitchcock has always been fascinating - for all their critical and professional associations, their approaches to Hitch have almost nothing to do with each other’s. While Hitchcock/Truffaut might be the enduring book on the master, Chabrol and Eric Rohmer’s Hitchcock: The First Forty-Four Films is every bit as valuable and insightful. There’s a level on which Hitchcock/Truffaut is a stroke-session between two men convinced of their own genius (you might call that the “primary level”) while the Chabrol/Rohmer book is all the more interesting for willing to be critical of the filmmaker* and honest about his worst tendencies.

Some of the phrases they use to describe Hitchcock’s infamous manipulation of his audience are brutally unforgiving: “sovereign contempt” or “that spirit of mystification.” Look at this bit about an early film they’re not fond of: “Too much in this film is sacrificed to what Orson Welles has called ‘pathetic tricks,’ and it is on the whole no more than a collection of superimpositions, distortions, speed-ups, an outpouring of frills and furbelows, of cumbersome feathers, of grotesque jewels.”

By contrast, Truffaut defended Hitchcock against the accusations of showiness that plagued him throughout his career by writing “A strong person may be genuinely cynical, whereas in a more sensitive nature, cynicism is merely a front… in the case of Alfred Hitchcock it is the facade that serves to conceal his pessimism.” Instead of calling Hitch out, he attempted to reimagine Hitchcock’s technical virtuosity (so frequently accused of being “empty” or “cynical”) into a philosophical-emotional gesture. He’s not self-interestedly manipulative, he’s pessimistic.

The Cahiers du Cinema critics who became revered filmmakers (Truffaut, Godard, Chabrol, Rohmer & Rivette) were contrarians to their core - and it comes out in weird ways, not just in that kind of defense Truffaut lays out for Hitchcock (which is their standard “what you think is bad about this filmmaker is actually good!”) but in more unexpected ways.

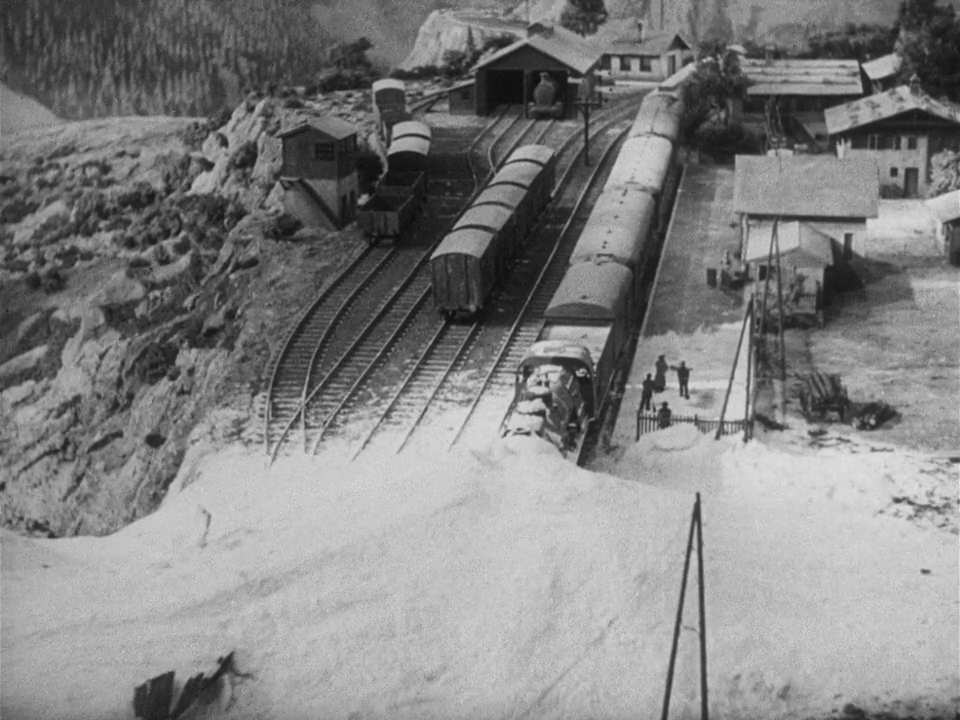

There’s an amazing bit in The First Forty-Four Films where, moving chronologically film by film through his work, after having spent significant time discussing forgotten works like Juno and the Paycock, they finally reach the apex of Hitchcock’s pre-Hollywood phase, The Lady Vanishes. This is all they have to say about it: “The Lady Vanishes is almost an encyclopedia. It is the exact summing up of the Gaumont-British series, and therefore requires little commentary. Its early parts feature the models and mechanical cars that Hitch loves to play with.”

And then they move on almost immediately. Again, there’s a contrast with Truffaut who in his book of interviews with Hitchcock has fawning discussions about Lady Vanishes that flow through a dozen discrete pages. That’s the difference between Truffaut and Chabrol: Truffaut makes a free-wheeling macro-level case for Hitchcock’s genius, while Chabrol/Rohmer’s book is at its most engaging when singling out unloved works like Rich and Strange or Under Capricorn in order to make detailed, slow-building defenses for them as essential masterpieces. In The First Forty-Four, a discussion of Jamaica Inn serves to set up their argument on behalf of Under Capricorn; details pulled from a negative appraisal of Mr. and Mrs. Smith hark back to and support their belief in the excellence of Rich and Strange.

The First Forty-Four as a whole is deft and specific using arguments against certain films to exult other movies - it attacks from a variety angles with an intellectual sleight of hand that is extremely difficult to counter. Even if you disagree about the relative quality of Murder! or The Man Who Knew Too Much, they make it extremely difficult to disagree with their thoughts on the work. On the other hand, Hitchcock/Truffaut is celebratory and theoretical with dozens of unsupported assertions** - it’s a book that’s fun and engaging*** and packed with ideas that are easy to poke holes in.

This contrast of approaches I think explains why when the filmmakers put on a Hitchcockian affect one of them made The Bride Wore Black, the “Hitchcock film” that isn’t, and the other made Masques, the slyly Hitchcockian thriller that fits into the director’s oeuvre in an interesting way. I’ve said more than all I have to say about Bride, so let’s move on more Chabrolulary activity.

We’ve written a lot about Chabrol for the site. It’s possible we’ve written about him more than any other filmmaker (although I don’t have the cold, hard stats to back me up on it.) And each time I have to begin the discussion by describing the recurring, damn near unyielding, Chabrol story-template. Because of his consistency, Hitchcock was a prime target for auteur-theorizing, but Chabrol's narrative and stylistic rigidity puts The Master's to shame.

Over and over Chabrol repeated a story-structure: a seemingly normal person is drawn into a bond with an overtly unhinged person…. and through this bond, the seemingly normal person is revealed to be the truly unstable one. He’s done some variation on this basic concept dozens of times, it’s a description that could apply to nearly all of his best movies.

And it can nearly be applied to Masques, which is nearly a good movie.

It’s not a bad movie, per se, but it is one with a strange tone and almost mysterious purpose. It gets described as a comedy just as frequently as it gets described as a Hitchcock homage, although there’s nothing notably more comedic about it than many of Chabrol's films (which in general would be ludicrous to describe as comedies.) His humor tends to be dry and derived from weirdness - Benoit Magimel hopping the fence to steal the statue in The Bridesmaid is a laugh out loud funny moment, but nothing about the humor of the situation is generated by traditionally comic means. It’s weird and funny and inexplicable, an expression of Chabrol’s talent for demonstrating that if you observe human beings with something like remote objectivity, you'll quickly notice they’re strange and gross and deluded and mean and selfish in a way that’s nevertheless engrossing if not out-and-out delightful.

It’s almost impossible to try to explicate how that sort of Buñuelian humor functions, how that “people are awful, I love them so much!” tone is achieved - Chabrol (along with Buñuel and Errol Morris) is one of cinema’s greatest practitioners of that elusive style. The downtrodden anti-heroes of La Ceremonie are wonderfully weird right up until the moment they shotgun a bourgeoisie family to death in their own home, possibly even as they’re shotgunning a bourgeoisie family to death in their own home. The scene is not a joke. The scene is not funny. The scene is horrifying and brutal. The scene is a culmination and expansion of the film’s sense of humor.

The combination of dark humor and a thriller framework might be why Chabrol occasionally gets referred to as “The French Hitchcock,” although the smirking and, yes, cynical humor of Hitchcock plays to an audience the way Chabrol’s work rarely does: Hitchcock constructs gags the way jokes are typically constructed: with set-ups and punchlines (like the car momentarily failing to sink in the swamp in Psycho) One of the reasons I think Masques does get called a comedy is that Chabrol, as part of his conscious homage to Hitchcock, includes several of these kind of Hitchcockian gags.

It’s tough to pinpoint when, where and why Chabrol started getting called “the French Hitchcock,”** ** especially since Henri-Georges Clouzot already owned the mantle, but Masques is one of the few instances where he seemed to lean into the idea and there’s a certain lack of seriousness that hangs over the film as a result - he’s goofing off, doing a little bit of an impression and it gives the whole film a breezy, flippant air. It resembles Chabrol’s other films in that despite the heavy presence of humor, it’s not really a comedy - the difference is that because of the fun he’s having goofing on the whole “French Hitchcock” bit it has a tone that somehow feels jokier than the rest of his work.

There’s a litany of references to Hitchcock’s work, some oblique, some blunt - and while some of them are "gags," the mere presence of the references contributes to the film’s uncertain “comedic” mood. Bad parodies make references without jokes to go along with them and Masques shares that tendency, any empty facsimile of “humor” that forgets to fill itself up with anything, you know, funny.

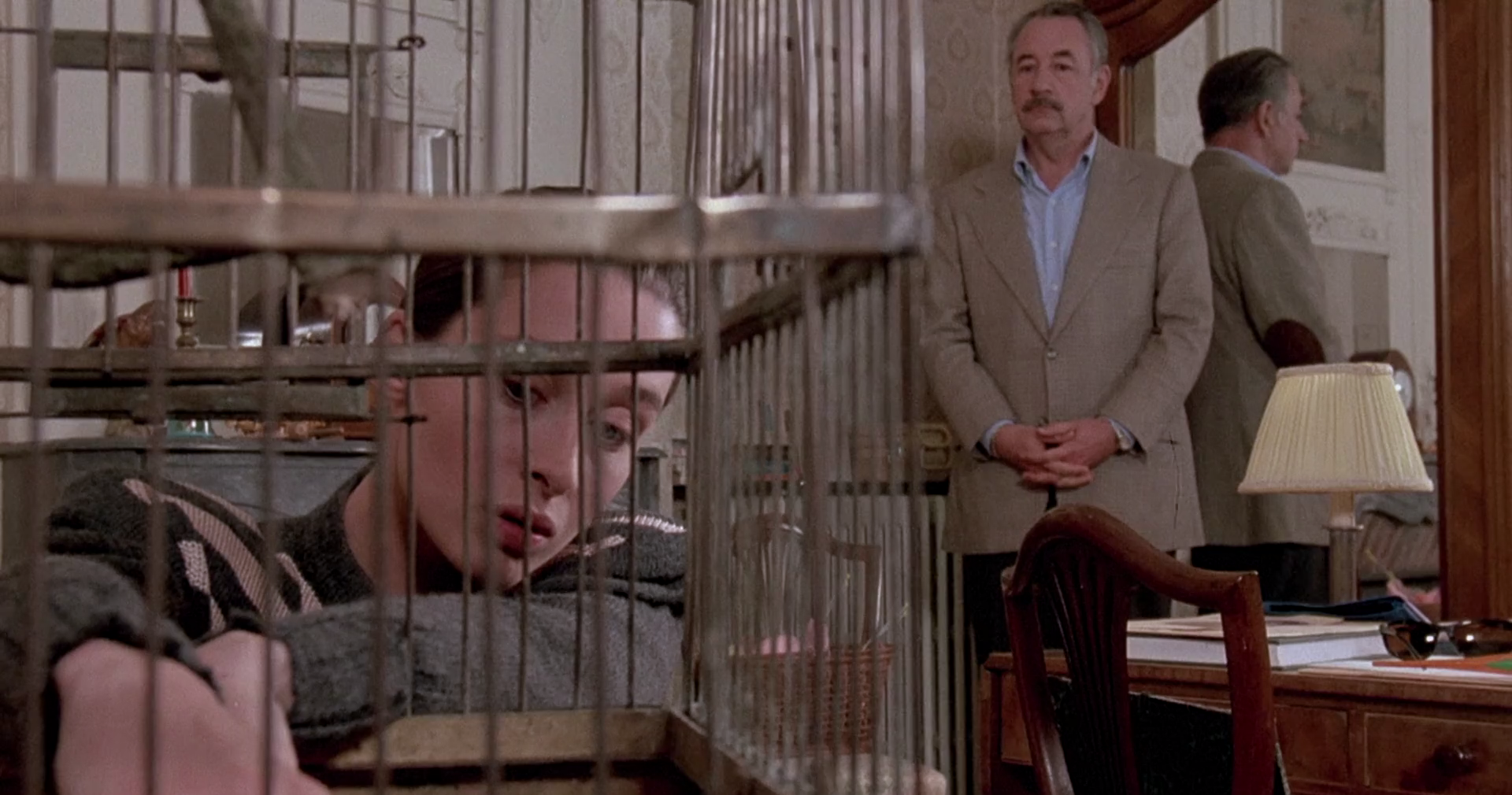

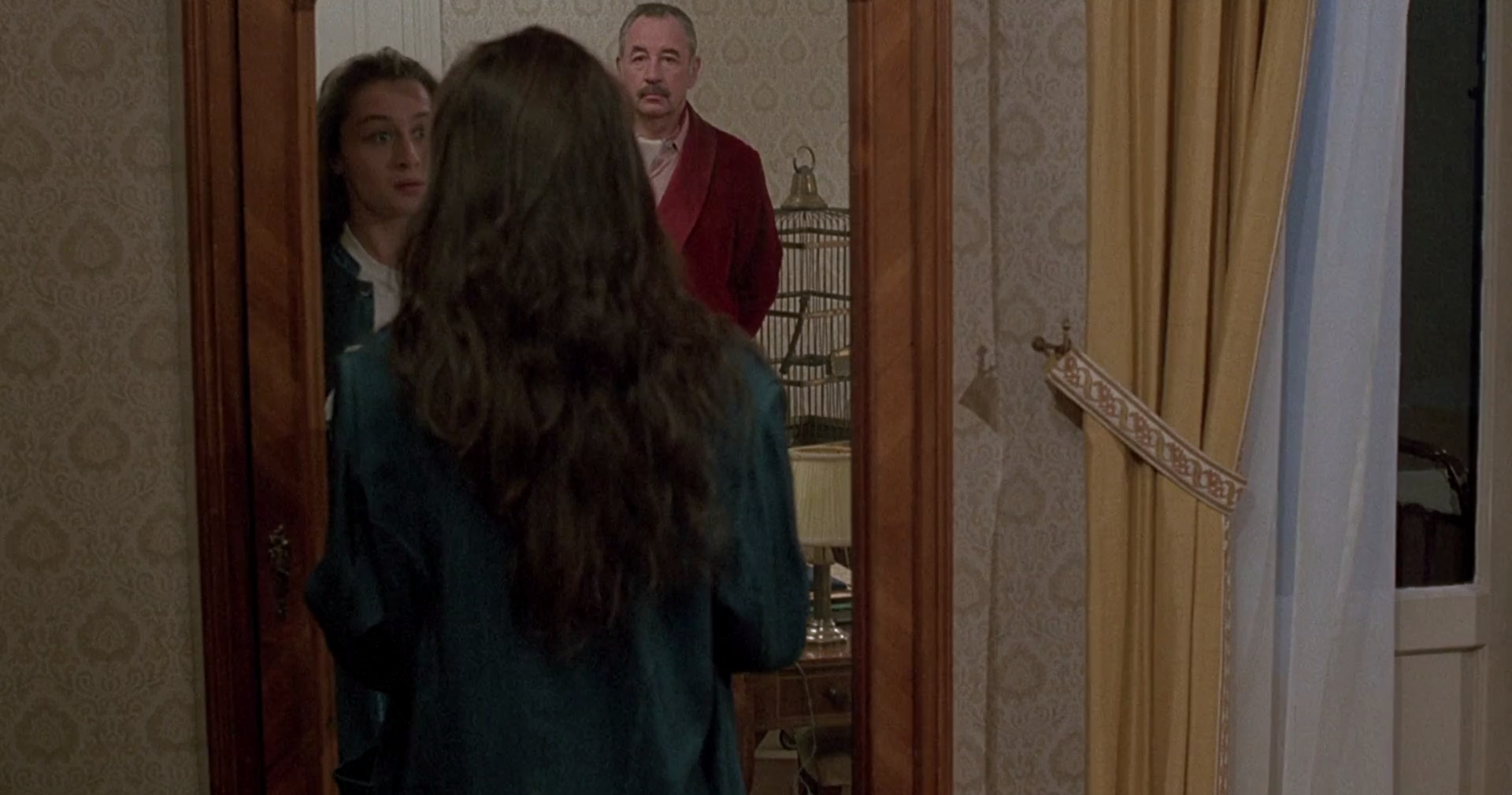

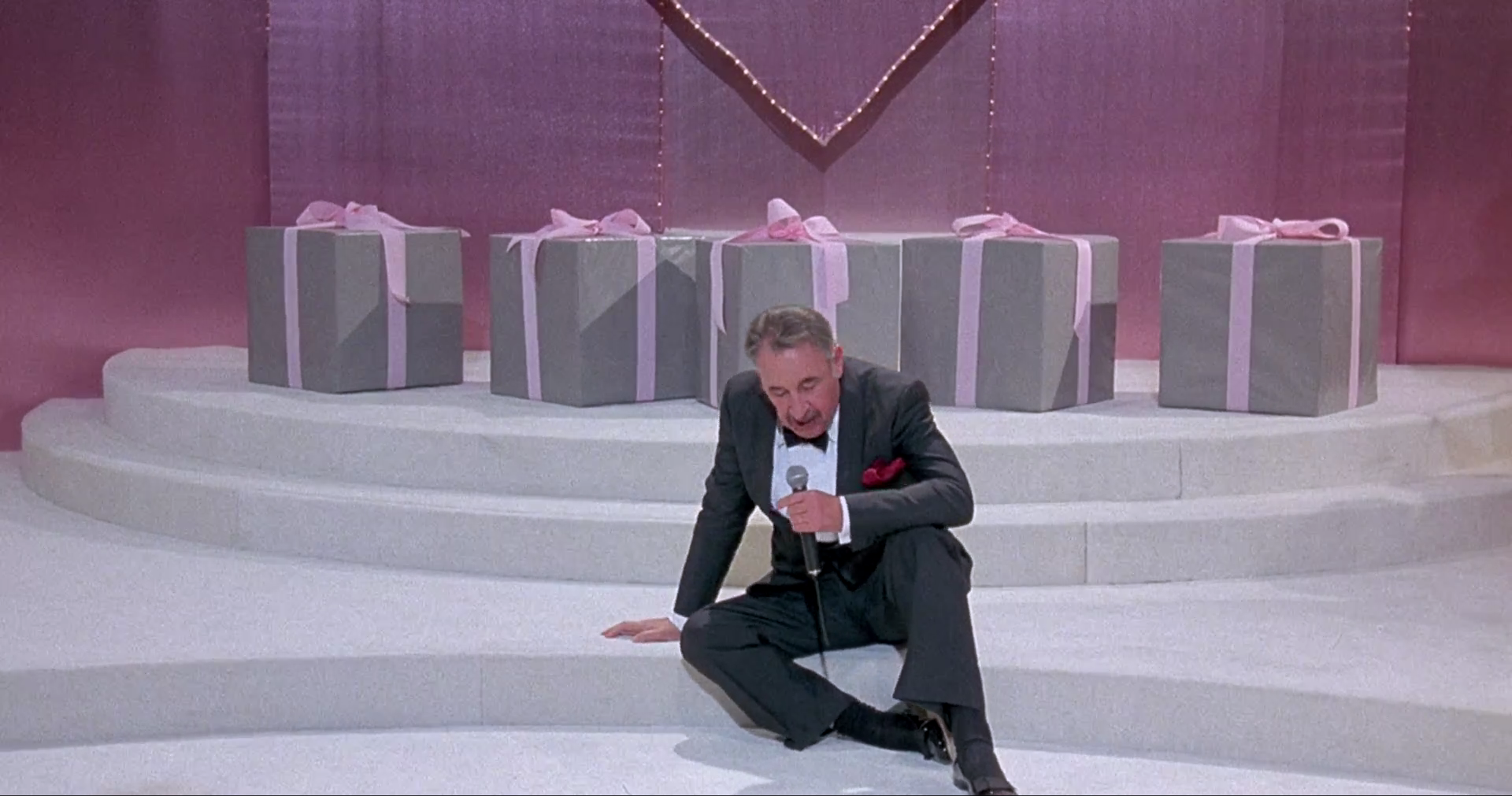

The story follows a ghost writer (Robin Renucci) hired to pen the autobiography of the host of a popular televised singing competition (Philippe Noiret.) We’re introduced to the character as he sits in the audience watching the singing competition. Like Robert Walker watching tennis in Strangers on a Train, he’s motionless as the rest of the crowd reacts to what they’re watching. That’s not really a joke. And while it's not a bad introduction to a character who has something to hide about his motivations for taking the writing assignment, it nevertheless instantly creates a strangely parodic tone that the film drifts in and out of.

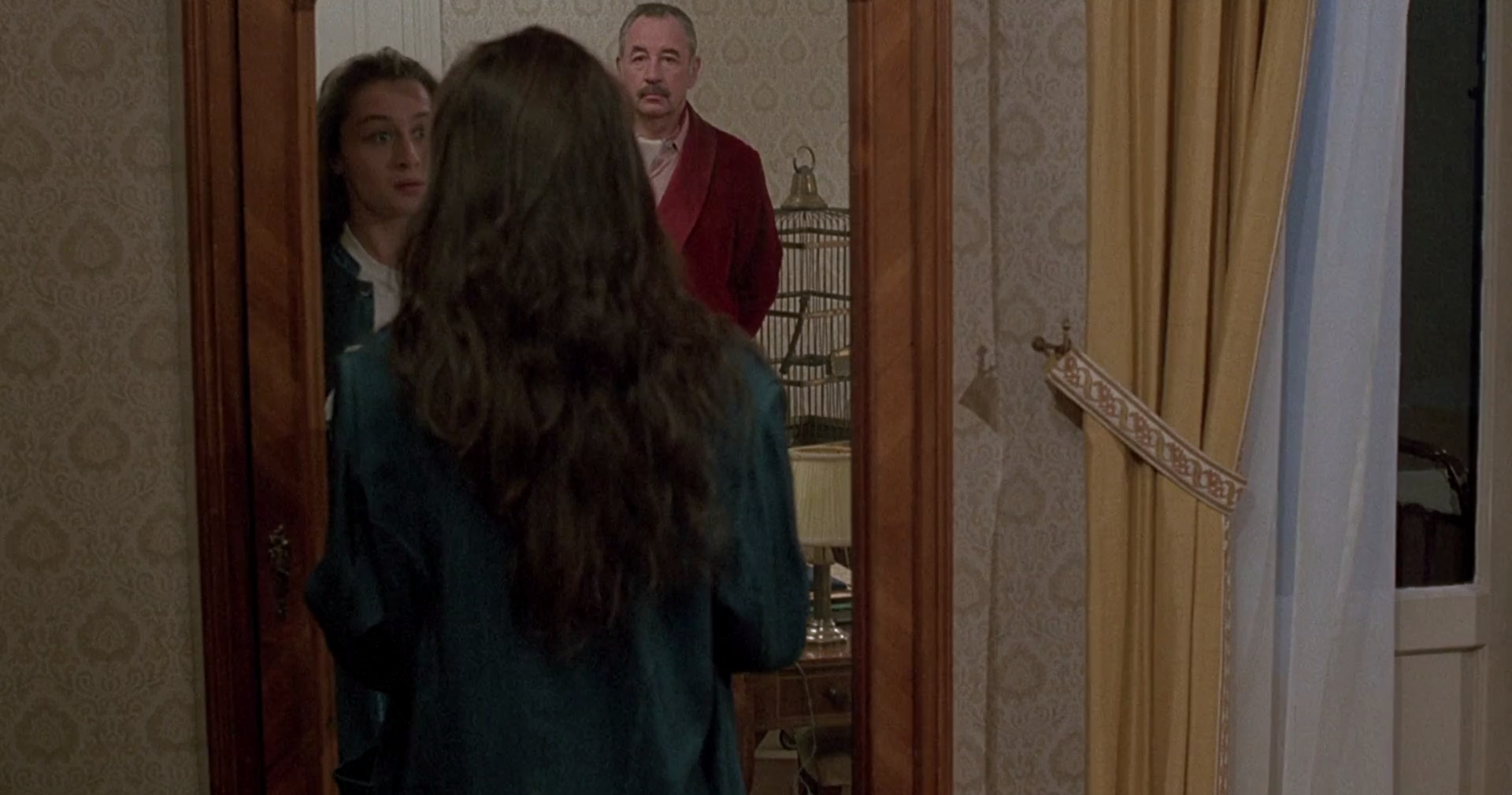

There’s nods to Hitchcock from start to stop - the Strangers on a Train theme extends into tennis as a recurring plot point and metaphor. It features so much wine and discussion of wine and a dank cellar filled with it, that you can’t help but think of Notorious - the same goes for the ominous staircase that the film takes a deliberate moment in the early going to draw attention to through an ostentatious deep-focus process shot. Bernadette LaFont’s hair is died an Aryan platinum blonde, so that when Chabrol gets her in that wine cellar, it’s impossible not to think about secret crypto-Nazi plots.

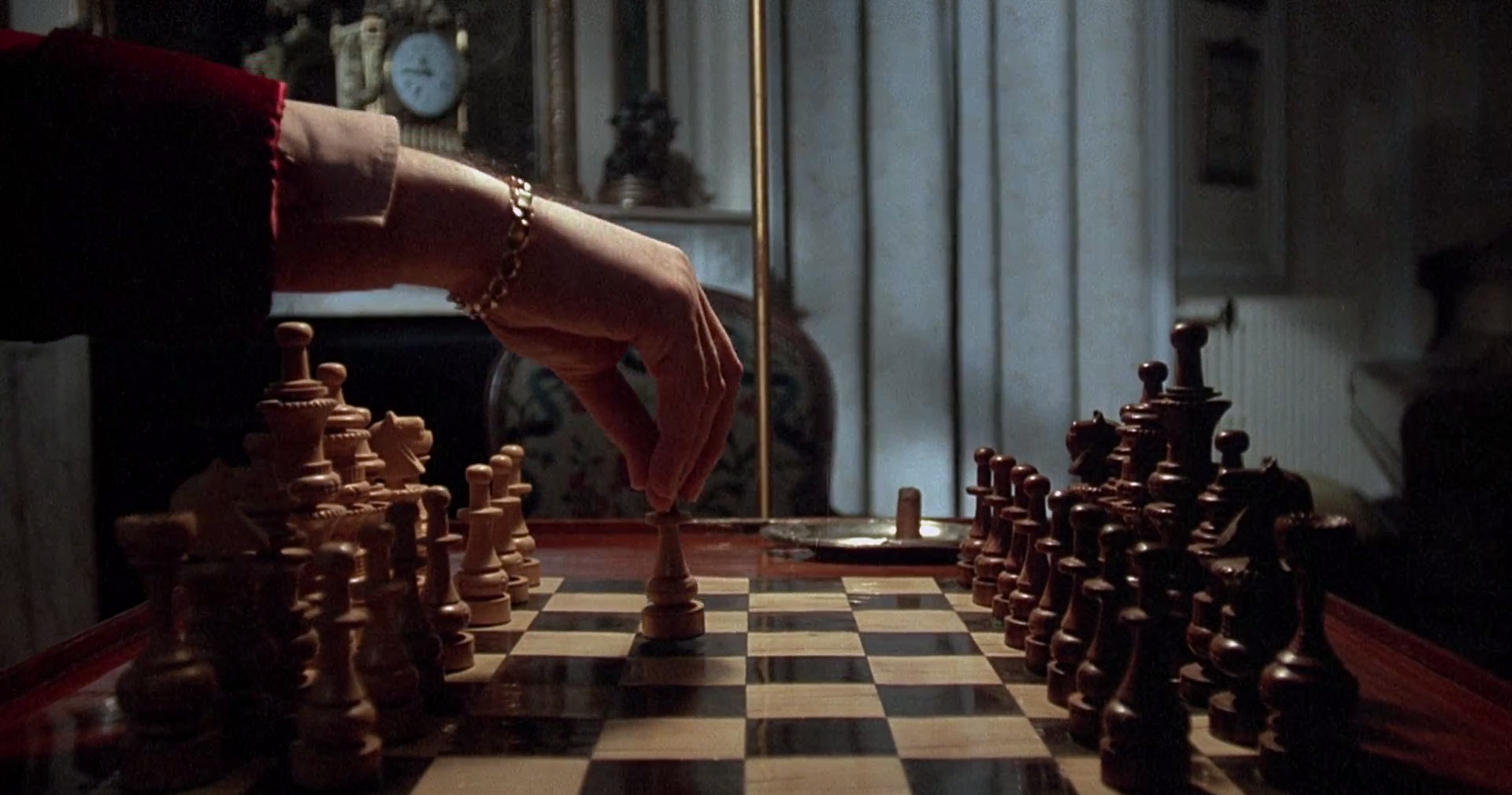

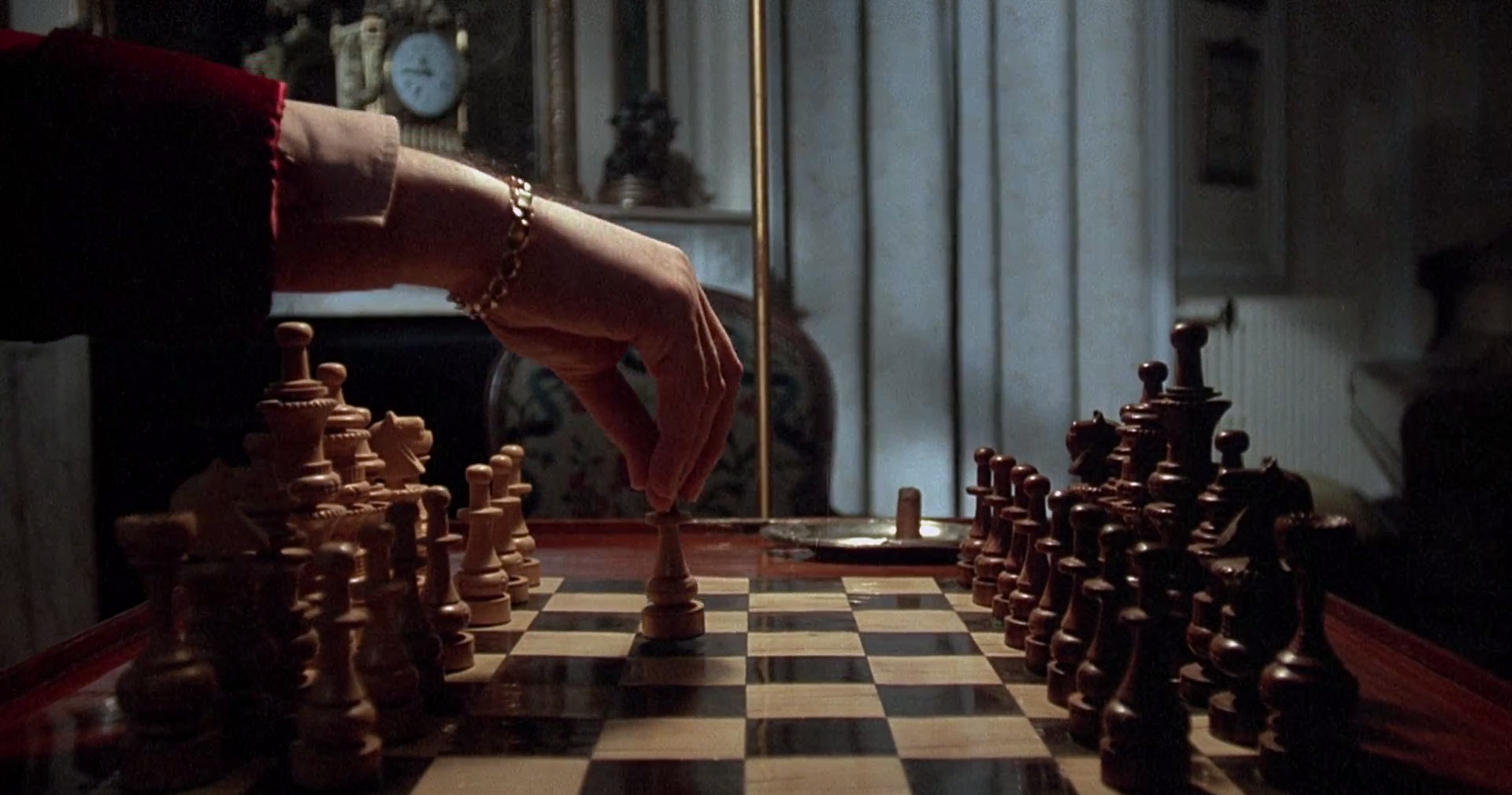

The film also imitates Hitchcock’s love of foreshadowing (“It’s like Bluebeard’s den in here!” the writer exclaims upon entering a closet with repertory costumes and mannequin heads) as well as Hitchcock’s love of cheesy symbolism*** ** with a climatic chess-match as our heroes match wits. To be fair to Hitchcock, he frequently includes these sort of gestures as a way of manipulating and undermining audience expectation - there is a humor to foreshadowing and symbolism in Hitchcock’s work in that he loves to pull the rug out unexpectedly via misdirection.

Chabrol understands that there’s humor to the symbolic foreshadowing - he includes a very Hitchcockian joke where as the writer and the t.v. host discuss the power and subtlety of metaphors, a statue of a young woman with her eyes blindfolded gets dropped and shattered… by a young woman with her eyes metaphorically blindfolded to the evil around her. The brute obviousness of it all is clearly meant as a joke. On the other hand, I’m not really sure the same should be said for another Hithcockoan “sight” metaphor in the film: the teenage girl also wears sunglasses the whole film… until she can see the truth! Then she takes them off. She even sunbaths. It goes to show: now she’s ready for some metaphorical chess!

That's not the only time it happens - the lack of seriousness in Chabrol’s homage frequently verges on going completely over the top. For example, the big finale of the film, the big reveal, is scored to a live rendition of Funeral March of a Marionette (a.k.a. the theme from Alfred Hitchcock Presents.) In his A.V. Club review, the great Noel Murray described the film as “a darkly comic TV mystery - more Alfred Hitchcock Presents than Alfred Hitchcock” and that seems about right, although there’s a chance that the t.v.-ish tone is intentional on Chabrol’s part. The film feels all too aware that it’s not Notorious, that it’s a bit trifling - that music cue is just a Mel Brooks-broad bit of goofing on the very concept of doing a "Hitchcock" flick.

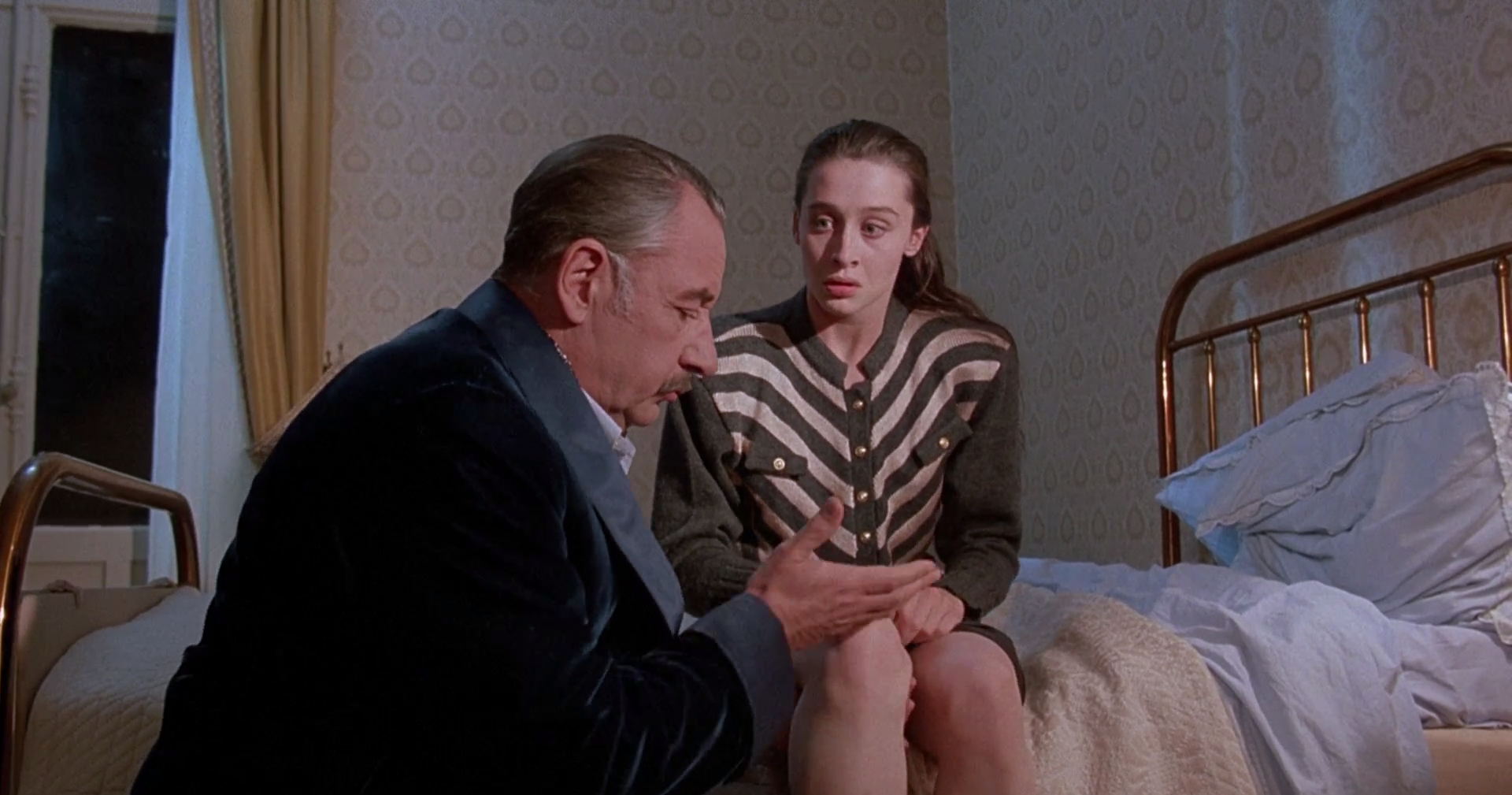

But what’s really weird is how closely it otherwise hews to that template for Chabrol’s work I laid out above (and in every piece I write about him.) When the writer gets to the country estate, he meets the t.v. host’s teenage goddaughter, who is now the t.v. host's ward after her parents died. (mysteriously.) The goddaughter is the young woman blind to the evil around her and like any goodie-goodie teenage girl in a Hitchcock film, her arc is accepting the evil in her everyday life, especially in the form of a male authority figure - Shadow of a Doubt, Rebecca, Suspicion, Jamaica Inn etc.

More importantly in regards to Chabrol, however, the daughter is an overt weirdo. And the t.v. host is a seemingly normal, likable, gregarious fellow. But the film reveals, via his bond with the girl, that the host is the true lunatic. It’s so close to being a typical Chabrol film!

Armond White had the essential observation that “Genre is Chabrol’s MacGuffin” and there is nothing more true that could be said about the filmmaker. Any MacGuffin needs to be destroyed (or otherwise rendered superfluous) well before the film is over - it doesn’t matter what’s in the briefcase or what happens to the stolen money, it’s all a springboard to a different set of narrative concerns. That’s so true of Chabrol’s use of genre: he employs genre elements only as a way of exploring his psychological concerns and his stories have a tendency to drift away from their ostensibly “central” narratives about missing neighbors and faked suicides.

When Chabrol tells a detective story, it's not because he's interested in presenting an engrossing crime and taking us through to the solution of its mystery, but because he's interested in the mind of the detective. His ideal Inspector Maigret story wouldn’t be about another shocking provincial murder, but one that focused on the detective’s ruined weekend plans and the dinners in cozy small-town bistros that Simenon loved to describe.

Masques is strange (for Chabrol) because it keeps its focus on the central plot and its resolution. By making Robin Renucci’s investigating novelist the main character, the story is kept outside of the “bond of insanity” that the director’s film usually exist within. “The really crazy one” becomes a traditional villain and the machinations of the plot are about stopping this character rather than exploring their psychological state. The perspective of La Ceremonie is positioned by the unhinged underclass duo, not the rich family they put in their (literal) sights - the film explores the duo's reality. (I should mention that Chabrol maintains remoteness even when "within" something.)

Despite the shift from Chabrol's usual perpsective, Masques comes very close to really working. At the climax of the film, after his nefarious plot has come unraveled, Noiret delivers on live television a bitter, mean-spirited monologue in the tradition of Joseph Cotton in Shadow of a Doubt - Noiret's delightful performance of this monologue alone makes the film worth watching, just as Cotton’s work in the otherwise limp and ineffective Doubt makes that film a near-classic.

Beyond that, a few of the suspense set-pieces in Masques rival anything Hitchcock ever committed to celluloid.*** *** At the end of the film, the young woman is trapped in the trunk of a car set for junking - our hero runs to save her even as it is being craned in the air to its destruction. It’s a great set-piece, the kind of pulse-pounding race against the clock Chabrol never really cared about milking in his other films. Although, I have no idea why the car she’s in the trunk of is a garish pink Cadillac. I suppose there’s something Hitchcock-y about that - a notbably weird object being the focus of a suspense set-piece.

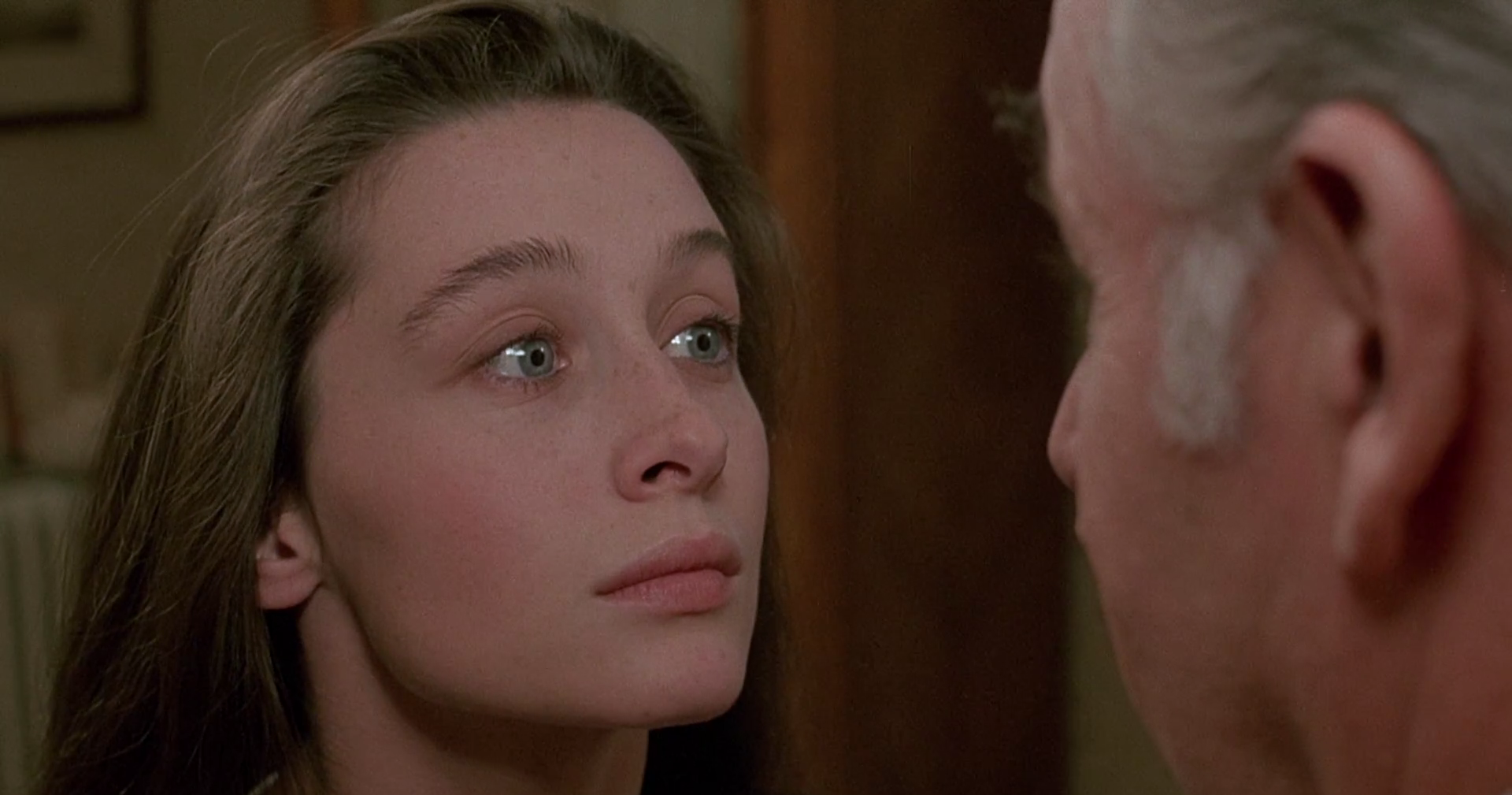

Anyhoo, I don’t think the real problem with the film is the preponderance of homages or Chabrol’s lack of seriousness or even that it goes off-model to focus on the writer instead of a psychotic duo. The real problem with the film is Anne Brochet. She plays the goddaughter and she’s the weak link. She’s not much of a star now, but in the late 80’s she was a real flavor of the month for Euro-artsy stuff - she played Roxanne opposite Depardieu in the 1990 Cyrano de Bergerac and the female lead in the mainly forgotten arthouse hit All the Mornings of the World.**** *** She’s not awful in Masques, but she needs to be brilliant for the film to come off.

Chabrol films have a tendency to be as interesting as their leading ladies - he gets away with bland male leads all the time (even in Masques), but it’s harder to think of good films of his that aren’t anchored by a really brilliant female performance (or two.) He of course made a half dozen or more flat-out masterpieces with his wife (and then ex-wife) Stephane Audran, doing the absolute best work of her career in films like Le Boucher, La Femme Infidele, La Rupture, Betty and Violette Noziere to name a few.

His late career alliance with Isabelle Huppert produced another half dozen brilliant works, including his greatest film La Ceremonie, which also featured an utterly stunning performance by Sandrine Bonnaire (giving my personal favorite performance ever. of. all. time.) The Bridesmaid thrives off of Laura Smet’s disquieting charisma. Chabrol’s one of the few directors to have successfully made use of Mathilda May’s prodigious allure (in Cry of the Owl) and in Ophelia he employed Alida Valli’s arresting eyes to full effectiveness.

When Chabrol ends up working with a movie star type at odds with his sensibility like Jodie Foster, Romy Schneider or Jennifer Beals,**** **** the films fizzle. Pair him with someone like Stefania Sandrelli or Marlene Jobert and it’s hopeless. For Chabrol, the actress really is the thing: his procedurals following male detectives (Cop au Vin, Blood Relatives, Inspecteur Lavardin & Inspector Bellamy) tend to be ok but lack real spark, whereas even a misfire like his version of Madame Bovary has something deeply compelling about it due to Huppert’s presence.

In A Girl Cut in Two Ludivine Sagnier provides the model for what Brochet needed to be in Masques: sweet and innocent but sexually-charged, seemingly manipulated by the older men around her but capable of seizing control of her situation in surprising ways, pure but immoral (her lust does not stain her) - above all, Sagnier is irresistible in A Girl Cut in Two.

In Masques, Brochet is eminently resistible.

The film can’t overcome it. She needs to shift between femme fatale, endangered naif, erotic tormentor, delusional danger to herself, manipulated fool, self-possessed woman and she can’t do any of it. There’s the line in the film “It’s very amusing to live several lives at once” - it’s extremely un-amusing to watch someone failing to live any.

It would be convenient to wrap up this piece by writing “And maybe that’s the most important lesson he failed to learn from Hitchcock: always have a Grace Kelly or Ingrid Bergman on hand or you’re doomed.” But I wouldn’t believe it. That’s the kind of dubious assertion I criticized Truffaut for making in his book with the big man himself. I’m not exactly sure if Masques doesn’t work because it fails to capture some essence of Hitchcock or if succeeding in capturing the essence of Hitchcock causes it to fail as a Chabrol film. But I bet Chabrol would have a detailed and sly take on the issue.

And it would be too good for me to argue against it. Even if I didn’t agree with it.

~ DECEMBER 5, 2016 ~

* This is your opportunity to tweet something coolly dismissive of the very concept! Do it! You’ll be an internet hero for your brave defense of the much-maligned Alfred Hitchcock! Take this bold stance now - sneer, snark and shrug in a gesture of dismissive superiority! "People write some crazy stuff on the internet," you'll tweet and you'll put a little whattayagunnado emoticon next to it and everyone will think "Well there's a guy who knows movies. Not like those guys who think Torn Curtain and Stage Fright are terrible." I just hope someone out there has the courage, integrity and intelligence to take this stance. Our willfully provocatively iconoclasm would be empty without an establishment orthodoxy to stick it to!

Or just, like, accept that not everyone likes the exact same films and filmmakers that you do, even ones as endlessly venerated as "The Master of Frills & Furbelows" (that was his nickname, right?) It happens. The fact of the matter is, we know our opinion on Hitchcock will be unpopular and we'd just like to move past it. If you think our assessment of him is indefensible, just know we have no desire to defend it.

* And while they’re merciless towards films they see as mercenary projects for Hitchcock like Easy Virtue or The Skin Game, they’re also surprisingly negative about several films that it would be reasonable to expect them to like - they call the original Man Who Knew Too Much “somewhat irritating and unsatisfying,” for example. That’s one of the few Hitchcock films I like! Incidentally, they also propose that “Sabotage is the Hitchcock film preferred by those who don’t like Hitchcock” but I find it to be an incredibly weak film precisely because it feels like Hitchcock at his most lazily and formulaically Hitchcock-y. Again, that’s a film that’s fairly well regarded nowadays, so it’s surprising to read them being utterly dismissive of it.

** For example, Cribbs does a great job of tearing down its “villain” theory in his piece on Topaz.

*** Of course it is: Hitchcock and Truffaut were two men who basically made careers out of selling themselves; Truffaut in terms of the insistent autobiography of his work and Hitchcock as his own public spokesman. They’re both also smart and engaging - Hitchcock is a born entertainer who throughout the interviews has a huge amount of awareness that he’s playing the role of a certain mythic version of “The Master of Suspense” for an adoring intellectual who is willing to spin wild, cool-sounding theories about the meaning and purpose of his work. It’s a really great read, even for those as heartless and snooty as us here at The Punk Smock.

** ** This BFI “Claude Chabrol: 10 Essential Films” article refers to him as “French Hitchcock” and then goes on to give a list that is goddamned insane for how inessential most of it is.

*** ** I always think of the painting of the snickering clown in Blackmail as the silliest example (intentionally silly, I think) but there are examples through his career.

*** *** Committed to Celluloid: The John Cribbs Story coming this spring from Puttynam Penguinoso Press.

**** *** She’s a much more interesting actress now that she’s settled into character acting roles, where her severe features and broad expressions are an asset instead of a hinderance. Weirdly, in Masques, from certain angles she closely resembles Emmanuelle Beart, who is similarly mediocre in one of Chabrol’s more inexplicable misfires, L’Enfer. That movie should be much, much better than it is. Hard to say what’s up here, with him having some creatively allergy to these two similar-looking ladies. It’s probably a gypsy curse of some kind, but that’s just speculation on my part.

**** **** I kept looking for a place to mention it in this piece, but I just couldn’t find it so I’ll attach it to my mention of Jennifer Beals. By the late 80’s, Chabrol was in a creative wilderness and seemed to being trying to homage his way out of his slump: he did Masques in ’87, adapted Strangers on a Train author Patricia Highsmith in 1988 and then did a truly bizarre Fritz Lang take-off/Dr. Mabuse crypto-remake called Club Extinction in 1990 (starring Jennifer Beals.)

I’m fascinated by this because there seems to be some kind of a Hitchcock/Lang connection in Chabrol’s mind. In The First Forty-Four Films, he compares the final shootout of The Man Who Knew Too Much to the shootout in Mabuse. Then when he hits a period of heavy homage, he focuses on Hitchcock and Lang. But what really made the synapses touch for me was the most overt homage in Masques isn’t even a Hitchcock reference, but a sloppily drawn letter “M” seen in a mirror! (M’s star Peter Lorre also playing the villain in The Man Who Knew Too Much.)

There’s no reason to include this in the body of this piece because I don’t think it actually adds up to something meaningful, but I think it’s a real connection that exists in his mind for whatever reason. It’s just kinda neat. That’s all. Not everything needs to a revelation. He also did a Henry Miller adaptation in 1990 and I don’t think that adds anything to the discussion.

Interestingly, the film that finally got him out of his slump and kicked off his late-career renaissance was Story of Women with Isabelle Huppert, a film that isn’t any kind of homage. It makes sense that an original film (even one based on a true story) would form the basis for his artistic resurrection.