iN ALEKSEi

GERMAN'S ORBiT

This month (June, in the futuristic year of 2018) writer Martin Kessler takes over The Pink Smoke with his five part series on Russian director Aleksei German, a titan of le cinema who is surprising obscure in the West.

Join us as Kessler explores the filmmaker's career, step by step: from medieval sci-fi to Soviet noir to wartime romance - German's body of work is brilliantly wild and unpredictable.

{PART I: ANOTHER CENTURY. ANOTHER PLANET}

{PART II: ESCAPE VELOCITY}

{PART III: APOAPSIS}

{PART IV: ECLIPSE}

{PART V: EVENT HORIZON}

PART V:

EVENT HORiZON

~ article by martin kessler ~

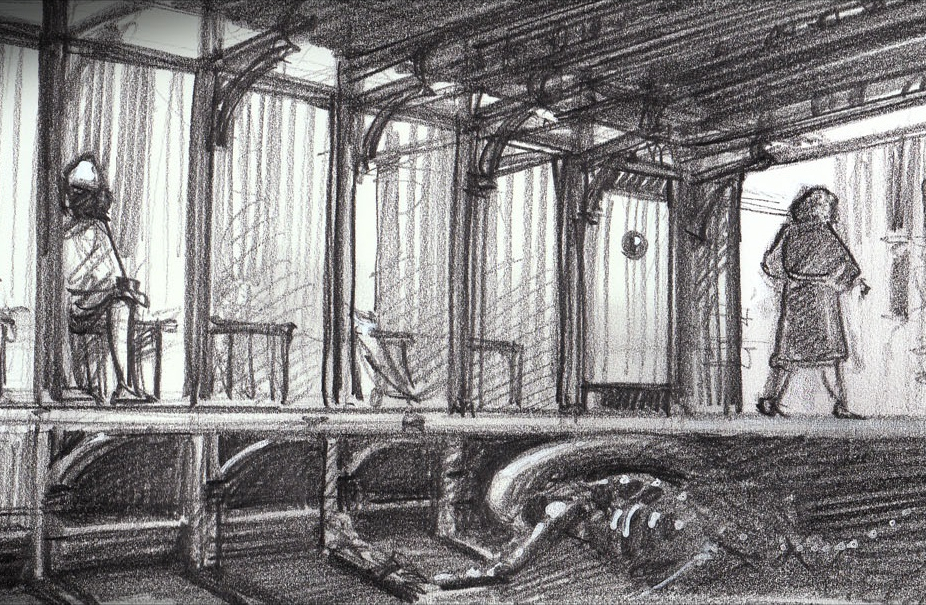

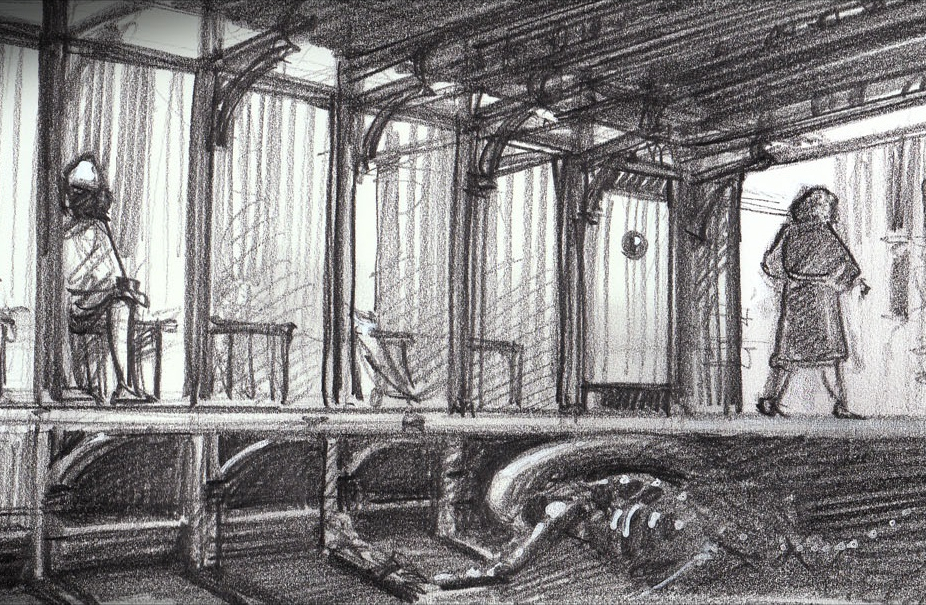

~ artwork by patrick horvath ~

Now my orbit is nearly complete, returning once again to where I began with Aleksei

German…

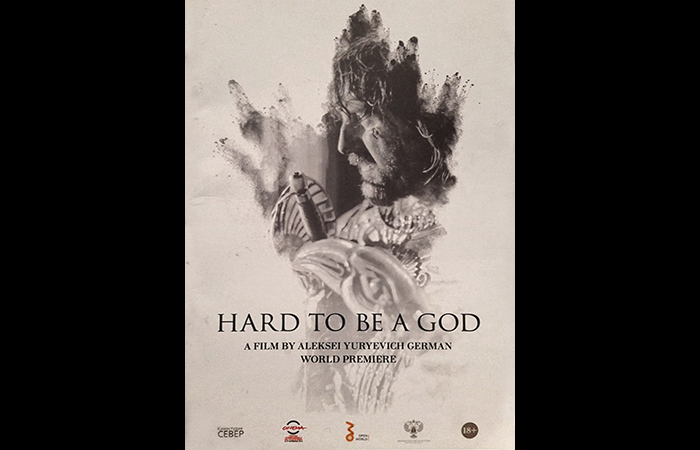

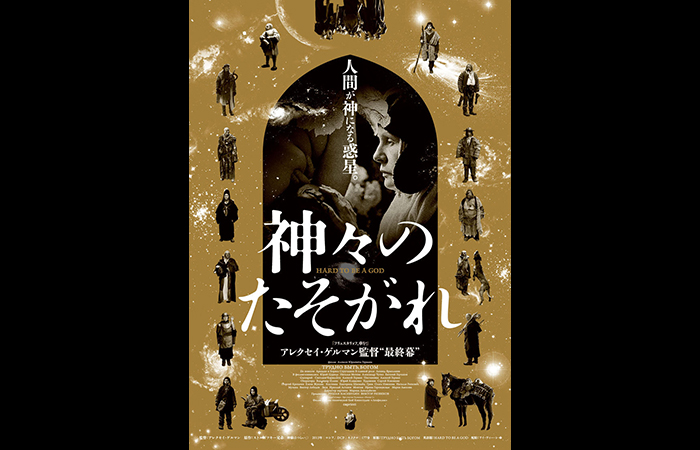

HARD TO BE A GOD

aleksei german, 2013.

Hard to Be a God is a film full of harmonious contradictions. It’s easy to see it as both an

outlier in Aleksei German’s filmography, and at the same time a perfect summation of his

filmmaking. It’s simultaneously the film in which German digs deepest into Russian specificity,

while also being his most universal film in its applicability. It's German's darkest film, but also

his funniest (or at least tied with Khrustalyov, My Car! in both respects).

Watching Hard to Be a God today, I’m struck by how human it is. Incredibly unsentimental,

and grotesque? Sure.... but unmistakably human.

There’s a bit of dialogue in Andrei Tarkovsky’s sci-fi film Solaris, “…we really have no desire to

conquer any cosmos. We want to extend the Earth up to its borders. We don't know what to

do with other worlds. We don't need other worlds. We need a mirror.” I think of that line less

as a didactic statement on humanity's place in the universe, and more just as a sort of ideal of

what science fiction can be. It’s a good line to keep in mind, when proceeding into the world

of Hard to Be a God. It’s set on an alien world, but an alien world that happens to be a mirror

to peer into, and glimpse ourselves in.

Hard to Be a God is set on a planet nearly identical to Earth, only a little smaller and more

prone to rain, with its local population in a state of civilization resembling Earth’s medieval

period. It’s unclear to the handful of Earthling scientists sent to observe, if this planet is

merely in a natural phase of its development toward an advanced civilization as some

theorize, or if it has permanently stagnated in its medieval state and will never progress

beyond it.

More specifically the film is set in the city-state of Arkanar, in which the main character, an

Earthling, has assumed the role of a noble Don named Rumata. He's introduced hungover and

begins playing jazz on a clarinet.

Rumata seems to become perpetually drunk throughout the film. Some locals believe that he

is divine and that he is “Descended from Goran, a local deity”. It’s not always taken too

seriously, though many are cautious of Rumata, and occasionally you’ll hear a line spoken like,

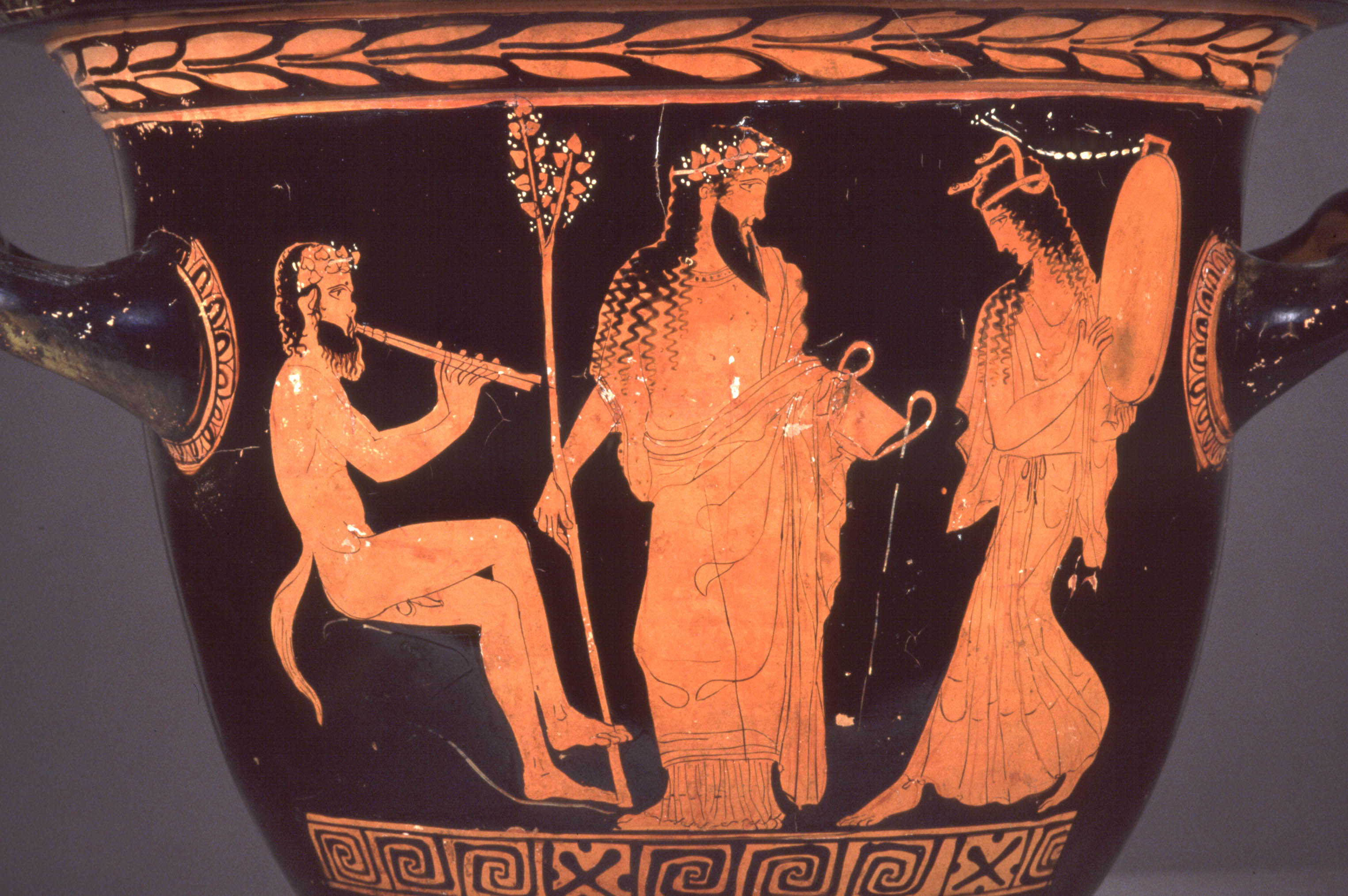

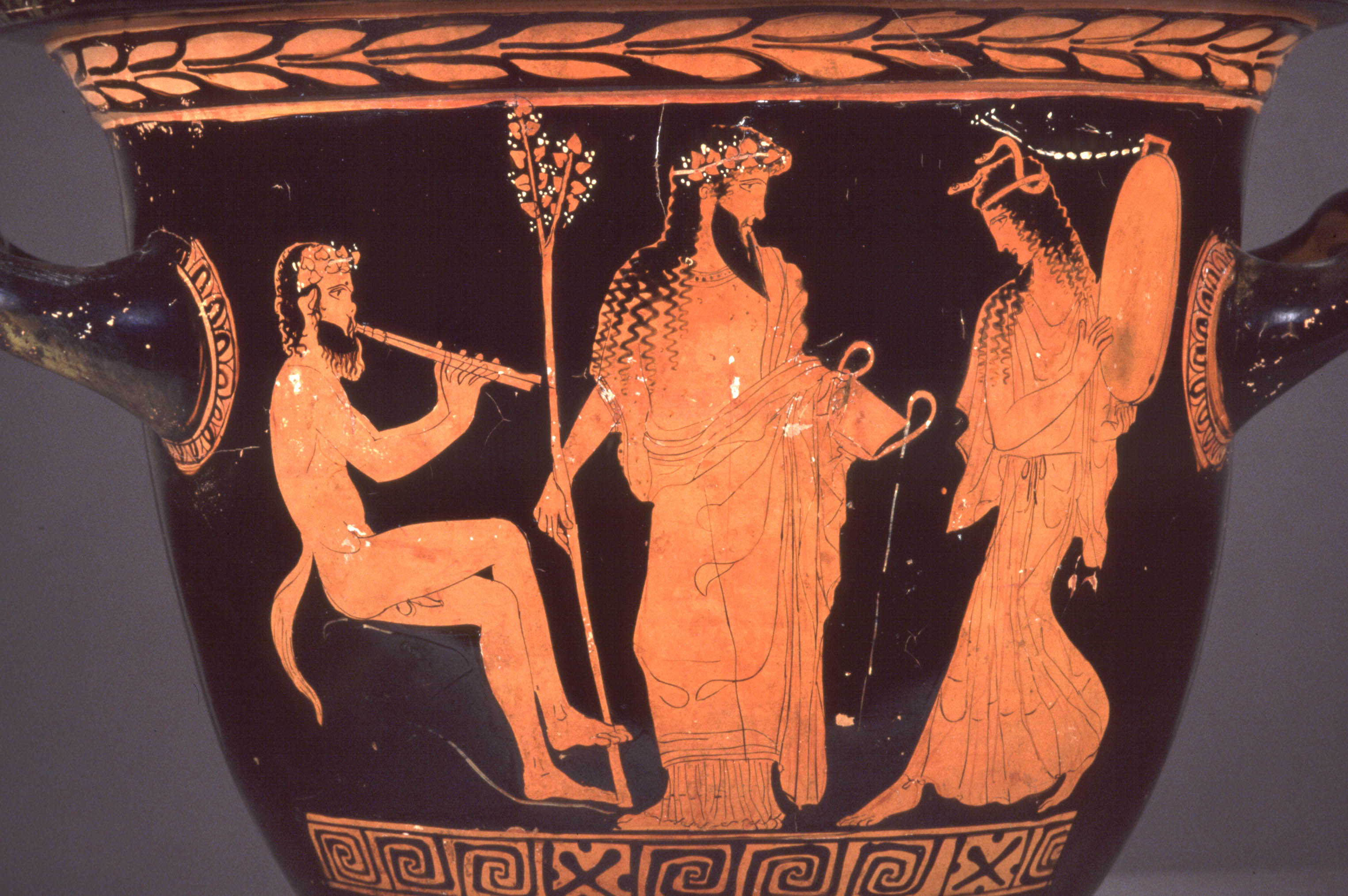

“Don Rumata, ask your dad to stop turning our wine sour.” I thought at first that ‘Goran’

sounds like the name of a god of war, or bloodshed, or something like that, but as I watch the

film again, I wonder if Goran is a god of alcohol and excess. Probably a bit like the Greek god

of alcohol and excess Dionysus (a.k.a Bacchus), as described in Euripides’ play The Bacchae.

It's a play about the god disguising himself as a mortal and coming to the city-state of Thebes

where he’s not worshipped. There Dionysus takes a revenge that is both comically absurd and

horrifically violent (or maybe comically violent and horrifically absurd).

In the Strugatsky brothers’ novel, it’s stated that the main character’s real name is Anton, but

he’s never called anything but Rumata in the film. It seems he has been playing the role for so

long that he has even come to think of himself as Don Rumata, at least to some extent. He

tries to stay clean while living amongst the excessive filth of the medieval planet. Over the

course of the film his tossing of handkerchiefs at the locals goes from a gesture of cleanliness

to a gesture of spite.

It’s clear that Rumata doesn’t get along particularly well with the other Earthling scientist,

who as the narrator explains “...drink more, and argue more, and gather less often.” It’s clear

they’ve been on the planet for far too long. They’re “Strange fools on a strange planet.” Later

in the film it’s implied that Don Rumata has been Don Rumata for about twenty years, so

assuming that a year for the medieval planet is about the same as one of Earth’s years, and

that the people of Arkanar have a calendar that's about as good as our Gregorian calendar,

then the Earthling have been on the planet for at least that amount of time. They’ve made

lives for themselves on this alien world, and one’s even adopted a local child, who happens to

be a total spoiled brat.

Rumata has a girlfriend who is a local. She's named Ari (played by Natalya Moteva in what’s

currently her only film role), and is much more fierce than her analogue in the novel, who is

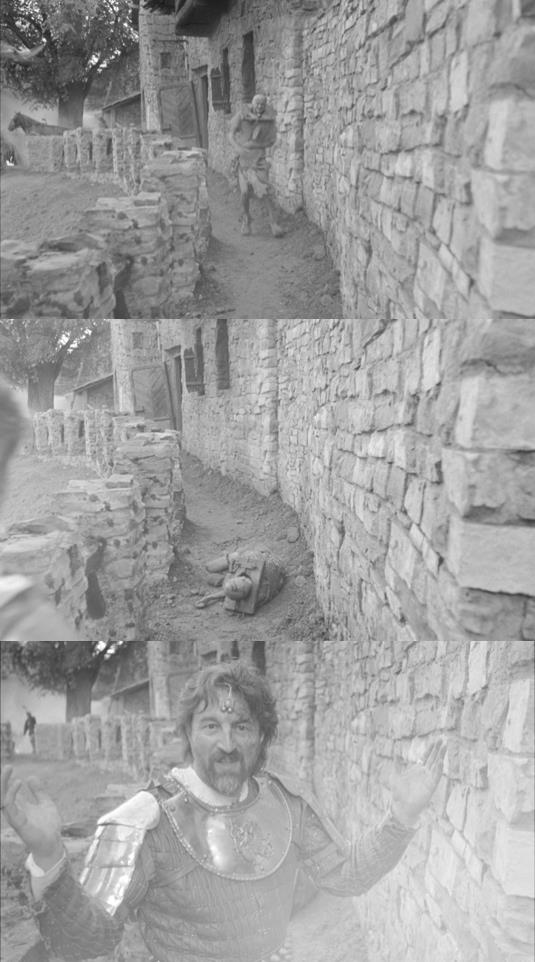

named Kira there. Rumata’s best friend is also a local. He is The Baron Pampa del Bao-no, or

just The Baron for short, and in spite of his bluster, he's is a bit of a softie. The Baron is played

by Khrustalyov, My Car! star Yuri Tsurilo, who comes across like an avuncular beer-bellied giant

in the role.

Rumata finds some of the other citizens of Arkanar to be endearing too. He’s not supposed to

interfere with the medieval civilization's course of development, but he’s often passing out

coins to anyone who has any spark of intelligence, or shows interest in art. Music especially

interests Rumata, as he’s always trying to teach a bit of jazz, and admiring any original piece of

music or creative instrument. Rumata’s not a fan of the traditional Arkanar music though, and

throws a bag of donkey shit at a grim Gregorian-like choir.

Rumata holds out hope that this civilization may produce its own Leonardo DeVinci. It seems

for a little while that there is potential in the Arkanar people to claw their way out of

medieveldom. One citizen Don Rumata talks to is even trying to learn how to fly, though only

“mostly downwards” with his pair of wood and vellum wings.

Any hope for progress in Arkanar is thrown into jeopardy as it descends into a wave of antiintellectualism,

lead by the thuggish faction called The Greys who are in-name in service of the

child-King, but follow the orders of their leader, the hunchback Arata (played by Valentin

Golubenko). The university is destroyed. Some artisans and ‘bookworms’ flee to the

neighbouring kingdom, Irukan. Other intellectuals are murdered. In one scene, a poet is

dropped into a deep latrine and drowned to death in shit.

At one point Rumata stops to admire an exquisite painting on a wall. Where is the artist?

Probably dead. I think one of the major things to take from Hard to Be a God is that in a world

where art has no value, neither does life.

There is also a growing resentment of redheads. It seems that in Arkanar, being ‘redheaded’

means more than simply someone’s hair being red. For instance it’s implied that a person's

mother or grandmother being a redhead is enough to make them qualify as a ‘redhead’. I take

it as an analogue to the homicidal anti-semitism of the 20th century (an extension of what

German touched on in Khrustalyov, My Car!), though by German abstracting that concept, it

can be viewed as an allegory for any society’s ethnic scapegoats.

Ari is a redhead, so she wants to get pregnant with Rumata’s child as insurance. “Goran’s

grandson will be my fangs,” she says before getting a slave to use a crowbar to pry off her

chastity belt. There are also rumours among citizens of Arkanar that Don Rumata himself may

secretly be a redhead.

Rumata hears rumours of a different nature, about a man named Budakh. He's a doctor who is

supposedly an intelligent and sober mind from Irukan. Budakh has disappeared in Arkanar and

will likely be killed. Rumata spends much of the film, trying to seek out Budakh to save him.

Rumata recognizes that he may soon find himself pulled directly into Arkanar's troubles. When

arguing with the captain of the royal guard over whether or not fish like milk, Rumata forces

the captain to call him a god. He calls Rumata a god. Rumata then asks, “If I am a god, why am

I on your arrest list?”

A small army of soldiers arrive to arrest Don Rumata. He brandishes two swords at them and

taps them together threateningly. Taka taka taka! The base of the scene is taken directly from

the novel, but German doesn’t treat it like the action set piece. It more closely resembles the

NKVD, showing up to make and arrest like you’d expect to see in Khrustalyov, My Car!.

Honestly there are are so many similarities between the films, that I think after watching

Khrustalyov, My Car!, it becomes easier to recognize the ways in which Hard to Be a God refers

to Stalinist society.

Don Rumata is unfazed by the soldiers. Still, they manage to capture him in a net (along with a

lieutenant accidentally). They take Rumata to Don Reba, a rival Don intent on grabbing power.

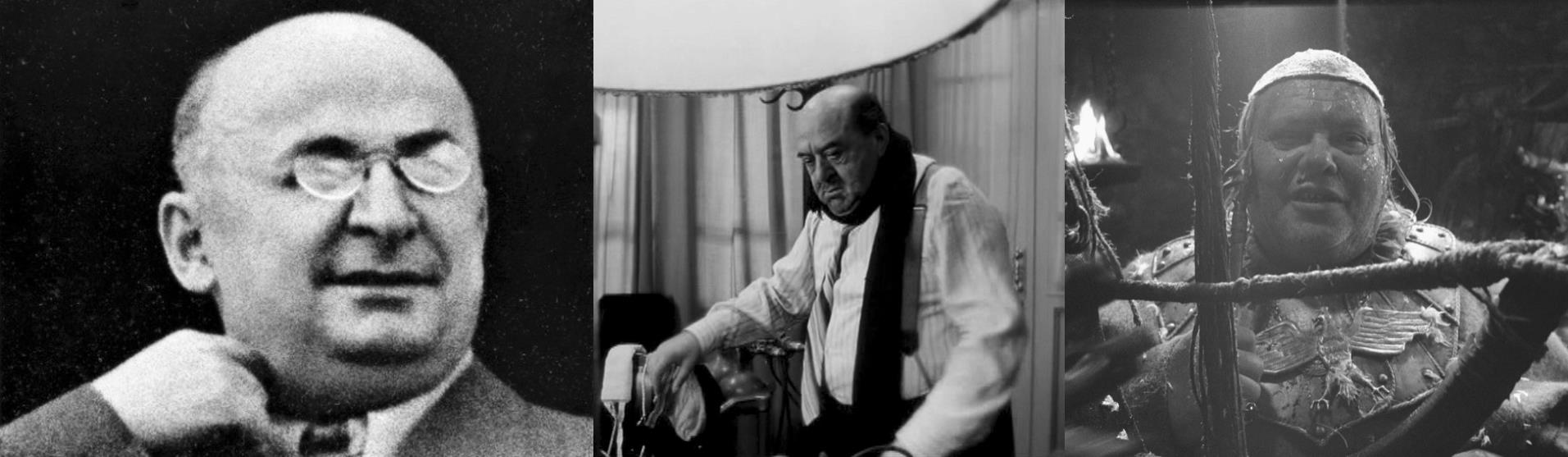

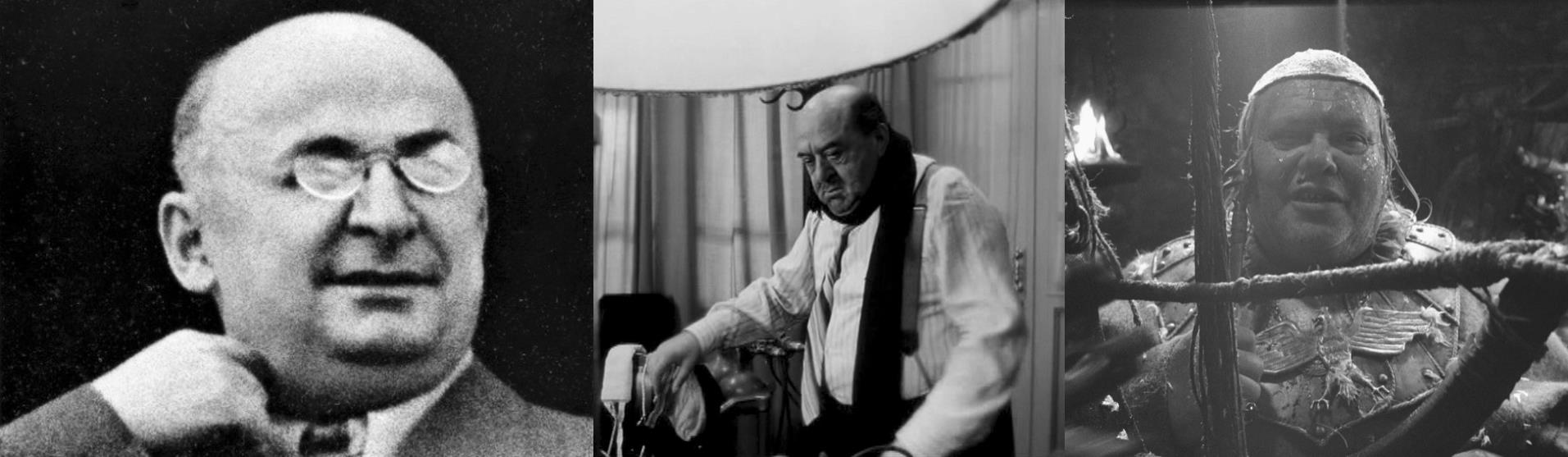

Knowing that the character of Don Reba was inspired by Beria, I couldn’t resit looking at the

historical Beria, next to the Beria of Khrustalyov, My Car!, next to Reba:

Don Reba has figured Rumata for an imposter and accuses him of being a redhead. There’s

another connection to Khrustalyov, My Car!, as Don Rumata asks Don Reba “Where’s your

doctor? …Not in a barrel I hope.” It’s a thinly veiled threat, suggesting the Reba may soon need

a doctor, but would be lacking as all the bookworms are being arrested and killed, just like

Stalin’s Doctor’s Plot.

Don Reba shows the dug-up skeleton of the real Don Rumata, who died of a disease at age 85.

He accuses Rumata of being a fraud. “Rumata, you’re a 105” Reba laughs. “What difference

does it make, plus or minus a legend?” Rumata retorts. “None at all in the new state,” Reba

replies ominously. Reba has also figured out that despite having been in numerous duels over

the years, Rumata has never actually killed anyone, only cut off ears. “Trust me, ears hurt,”

Rumata insists, but Reba isn't so intimidated by that.

Reba shows Rumata the arrival of The Order; 30, 000 men who show up to back Reba’s power

play. The narrator compares them to Brazilian ants and also explains that this faction is called

The Blacks. They’ll fight with and displace the regime of The Greys, functioning as a sort of

inquisition under Reba, even though Reba himself is afraid of slipping into heresy, because

there will be “no privileges for Dons under The Order.” Don Rumata uses Reba's fear of heresy

to talk his way out of the dangerous situation he's found himself in. He asks if he can take

Budakh out of Reba's custody too.

Rumata leaves Reba’s tower to find many of the intellectuals already dead. Hanged.

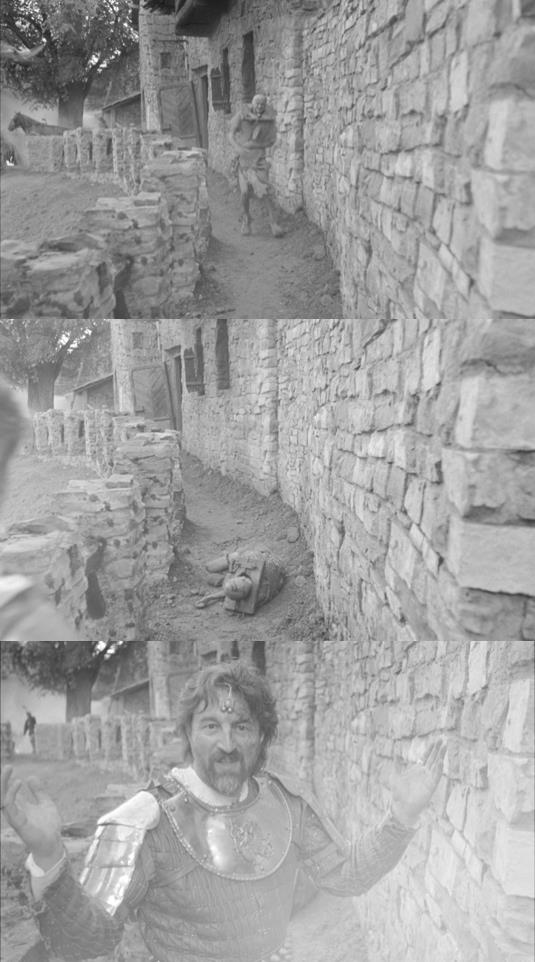

In a moment of spontaneity, Rumata decides to free a slave. He’s told the slave will die if he’s

freed. Rumata breaks the slave’s chains, and watches as the terrified slave runs about ten feet,

then drops dead in a panic. Rumata shrugs into the camera. Freedom can be overwhelming.

Freedom can be scary.

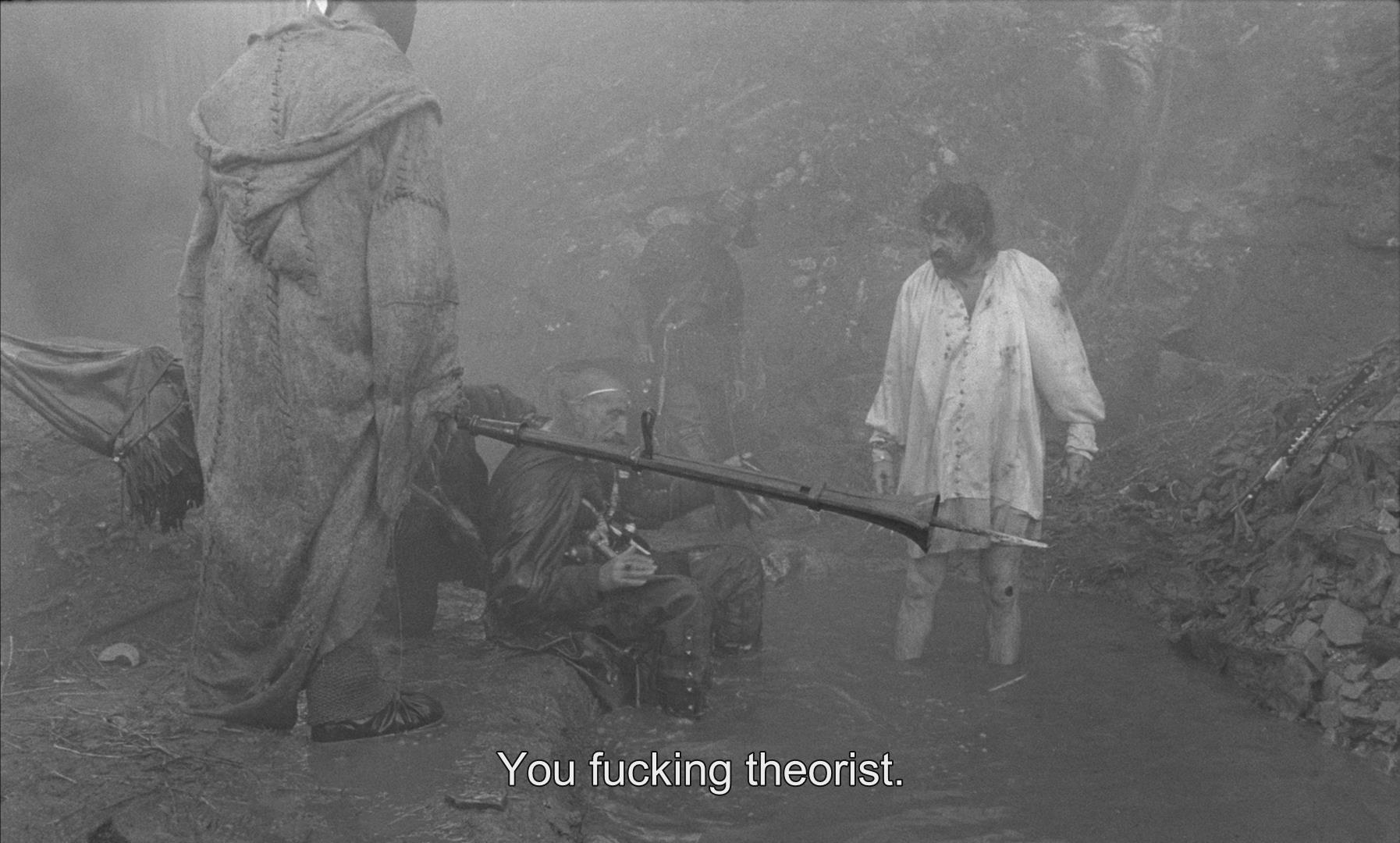

The Black's inquisition goes into full swing. “We’re killing whores,” someone says when

Rumata raises an eyebrow over a giant spring-loaded dildo-spear. People are slowly burned

alive in ‘The Liberated Arkanar’. The narrator explains that for Rumata, “A thought entered his

head and settled there for good. That he should kill Don Reba. Just kill him and not think

about the consequences.”

Don Rumata continues asking for Budakh, and finally gets what appears to be an answer. He

enters The Black's prison and torture chamber. He finds his friend The Baron there, locked in a

tiny cage. Apparently he was captured by having a cow thrown on him from a bridge. Rumata

rescues The Baron by knocking out the guard with a metal pot. The Baron says that he looks

forward to them cracking his captors’ “lousy skulls under our baronial swords!”

Rumata believes the finally, miraculously has Budakh been released to him (the guard even

reassuringly specifies “Budakh, not Rudakh”), but it’s hinted that this Budakh he is given is

really an imposter. Before too long it becomes apparent that this man who was supposed to

be a great doctor and brilliant intellectual is nothing but a nose-picking idiot. Like getting stuck

with the Klensky double rather than the real Klensky of Khrustalyov, My Car!.

The Baron is killed by archers as they leave The Black's prison. Left on a trash heap in the rain,

the narrator explains that at night paupers will take everything off of his body. A stranger

walking by chases away a boy trying to take the dead Baron’s sword, and then the stranger

takes a moment to put a hat on the dead Baron in a small gesture of respect or compassion.

So, the Budakh that Rumata has found is not the real Budakh, but Rumata is of course not the

real Don Rumata, so it may as well be Budakh speaking to Don Rumata. He asks Budakh for

advice, “What would you do if you were god?” Budakh tells him “Give people everything that

separates them.” But Rumata knows that the strong will take from the weak. Budakh corrects

and tells him “Punish the strong” but the strongest of the weak will take their place. It

resembles a dialogue from the novel, only there it is the true and intelligent Budakh answering

the questions, so things play out differently.

“You are a fool Budakh,” Rumata finally admits mostly to himself. It's revealed that this

Budakh has been sent to pour acid to pour on Rumata’s face, but is unsuccessful in carrying

out that command. The false Budakh is as good a representative of Arkanar as any, so Rumata

asks once and for all what God should do with them. The novel's Budakh suggests that God

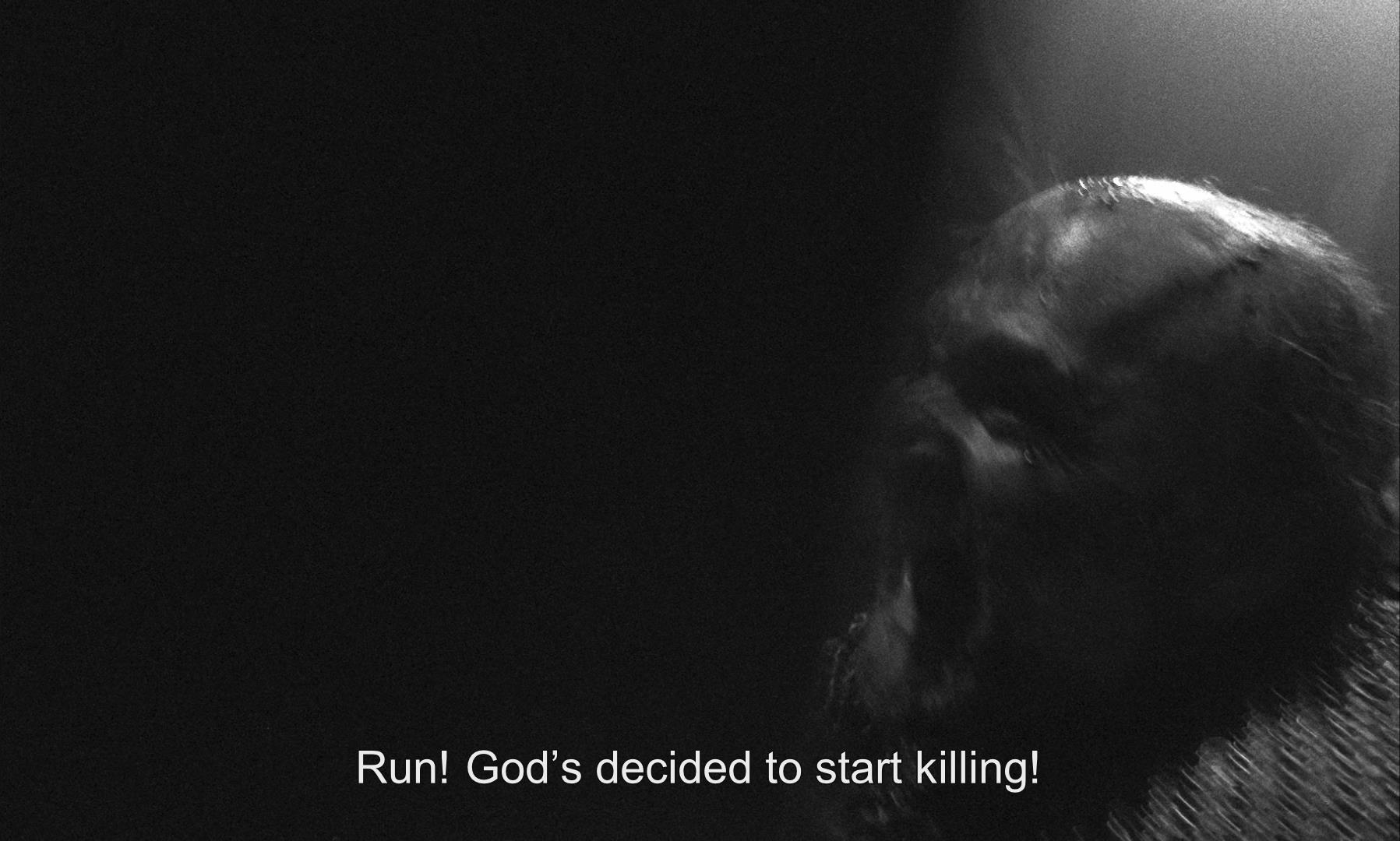

simply leave them be, however the film's Budakh says, “God if you exist, blow us away. Blow

us away like dust or pus.... Destroy us all.” God damn muzhik.

Things get worse. The Blacks and The Greys fight with one another, and the people in between

are killed or enslaved. 'Hats of sorrow' are distributed (presumably marking someone to be

burned at the stake). Rumata's girlfriend Ari receives a summons to the ominous 'Tower of

Joy'. “I almost forgot you were a god” the hunchback Arata says to Rumata, observing his

continued refusal to become involved in it all.

Even Ari urges Rumata to become involved. “Eighteen noble generations and no pants. Get me

pants and I’ll go to war,” he grumbles to her. She goes to find his pants and cracks up laughing

because, “The turtle was eating mice in the pants!” Suddenly, an arrow flies through the

window and into her head killing her. She lays on the ground dead, the arrow sticking out of

her still smiling face.

In the novel, the death of Rumata's sweetheart drives him into a vengeful rage, however in the

film it is more like the straw that broke the camel's back. Rumata has lost his best friend, the

intellectuals are dead, Budak turns out to be a fool, and finally his lover is killed. With nothing

good left, what is he to do? It is with great reluctance and a heavy heart that he becomes a

one-man slaughterhouse.

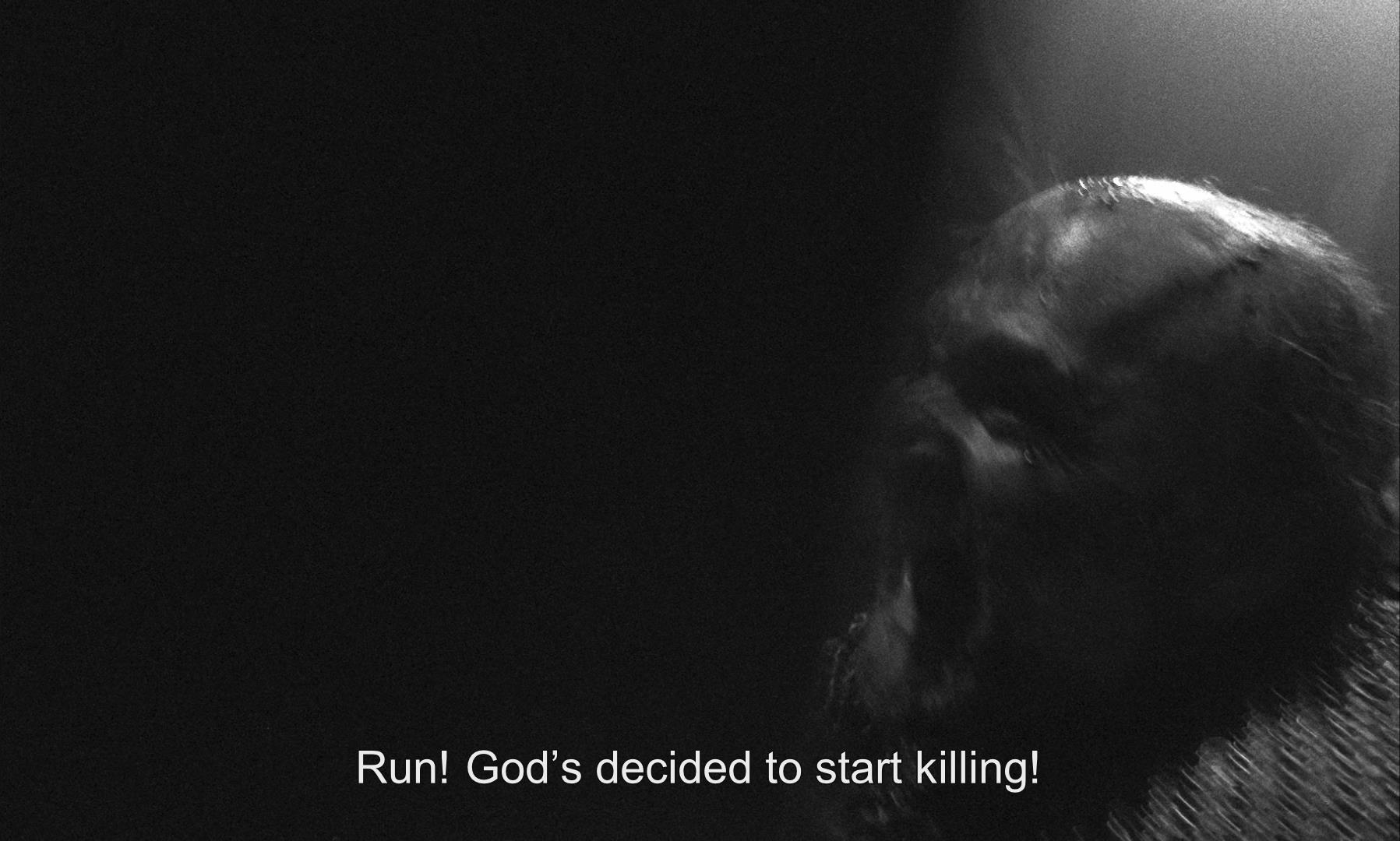

“God, if you exists, stop me,” Rumata quietly prays as he puts on a horned helmet.

Wearing his helmet, Rumata looks like some pagan deity, probably with a name like Goran.

When I read about German’s attempt to adapt Schwartz’ The Dragon, and wonder how the

dragon itself may have been depicted. I imagine it may have been something like this. Slay the

dragon in each and every one of them!

Rumata commits genocide on the people of Arkanar.

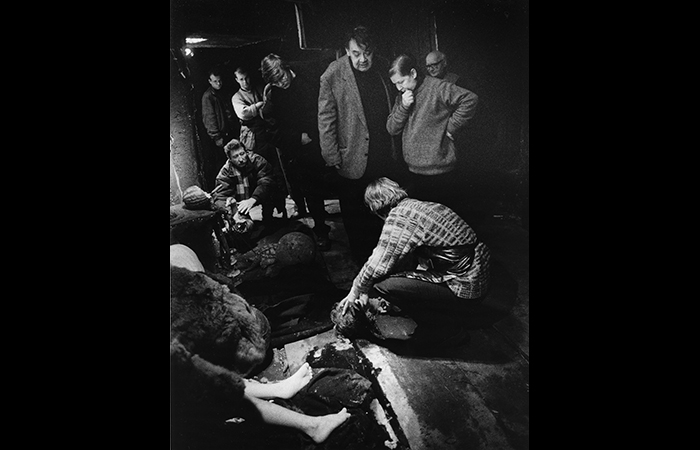

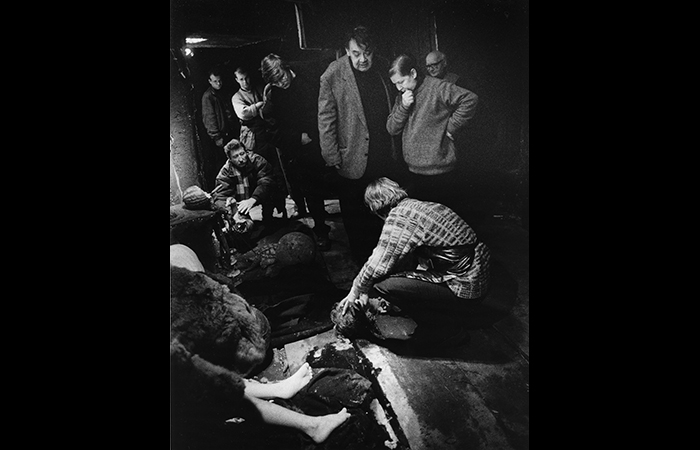

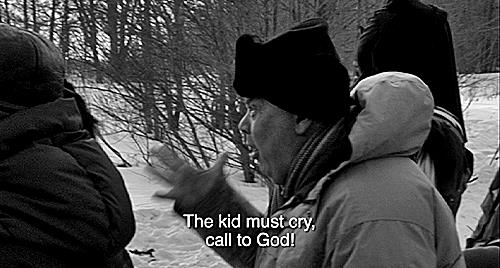

German spares us most of the slaughter. In behind-the-scenes footage he talks about

struggling with why human beings kill one another. It's a concept he's approached from

different angles throughout his films. I think back to that moving scene with the bridge and

the barge full of POWs in Trial on the Road, where the decision not to kill was so self-apparent.

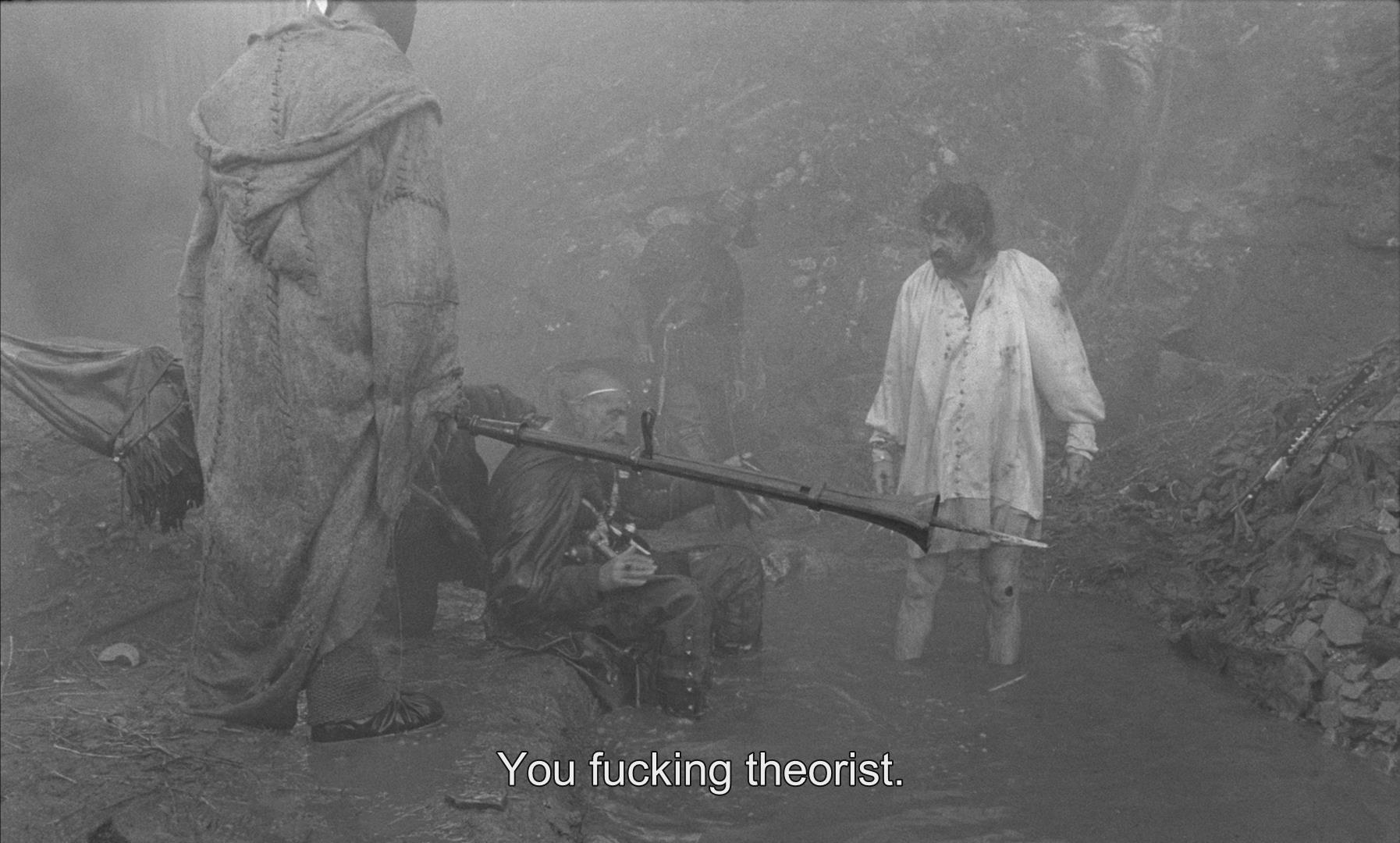

Some of the earthlings show up and wade through Rumata’s massacre. The hunchback Arata

is dead. Don Reba is dead. The Grays and the Blacks are all dead. At the centre of it all, the

Earthlings find Rumata himself, sitting in a puddle. “I’m not flying back to earth with you,” he

tells them.

Rumata has a brief argument with his fellow Earthlings, which concludes with him saying, “If

you write about me, and you’ll probably have to. Say that it’s hard to be a god.”

To err is divine, to forgive is human.

The film isn’t over yet though. Its final scene is a epilogue in winter. Rumata seems to have

aged about a decade. His hair long hair has been cut and he's wearing glasses. He stays on the

planet with his clarinet, a memento of civilization, trying to teach jazz.

I don’t know, it gives me a tummy ache.

There's a traditional genre of music called Dumka, which is sort of the Slavic equivalent to the

Blues. Dumka is typically melancholic though not solemn, and I've always been told that it's

music to make you think. For me, watching Hard to Be a God is very much like listening to

Dumka. The more I think about it, the more Hard to Be a God sounds like the title of some old

Delta Blues song.

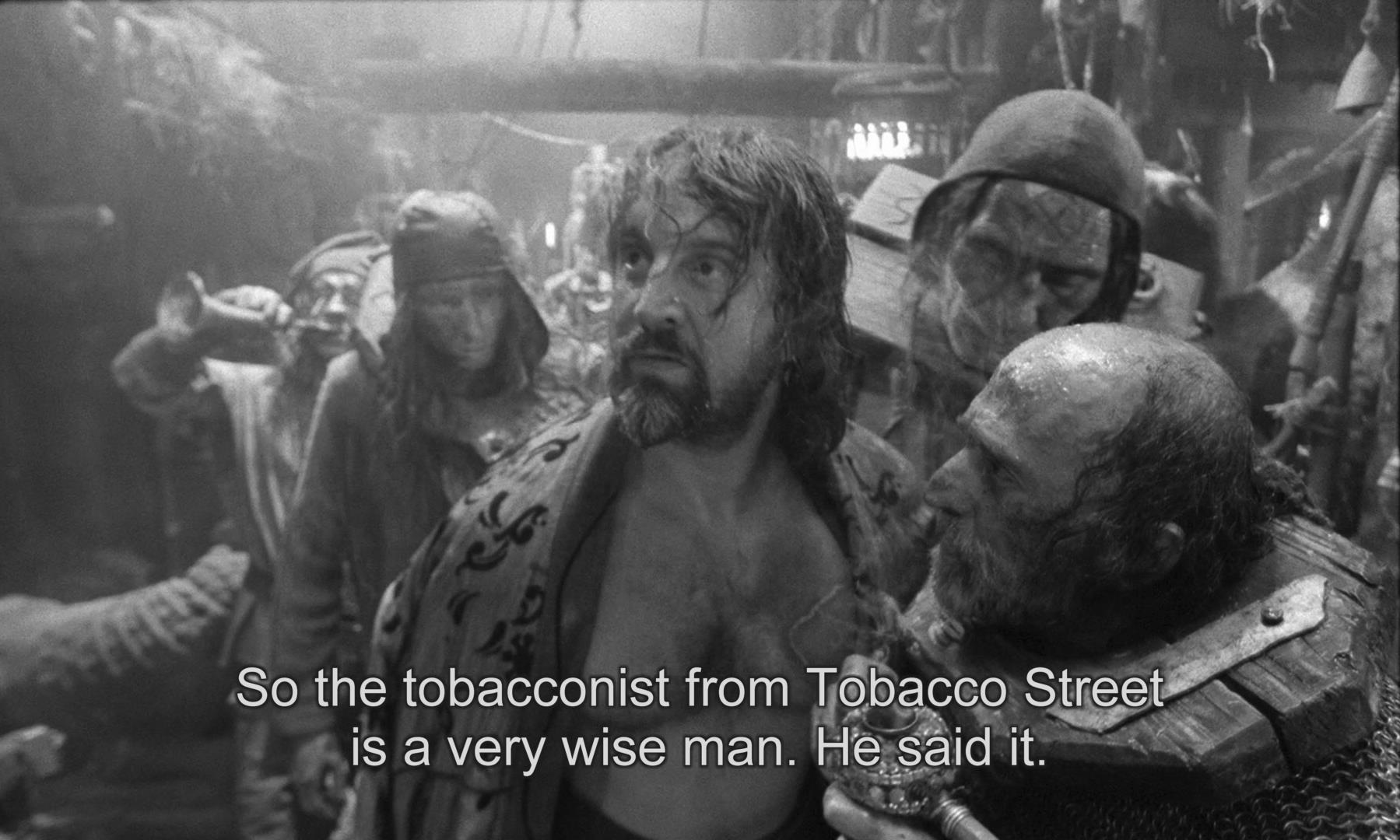

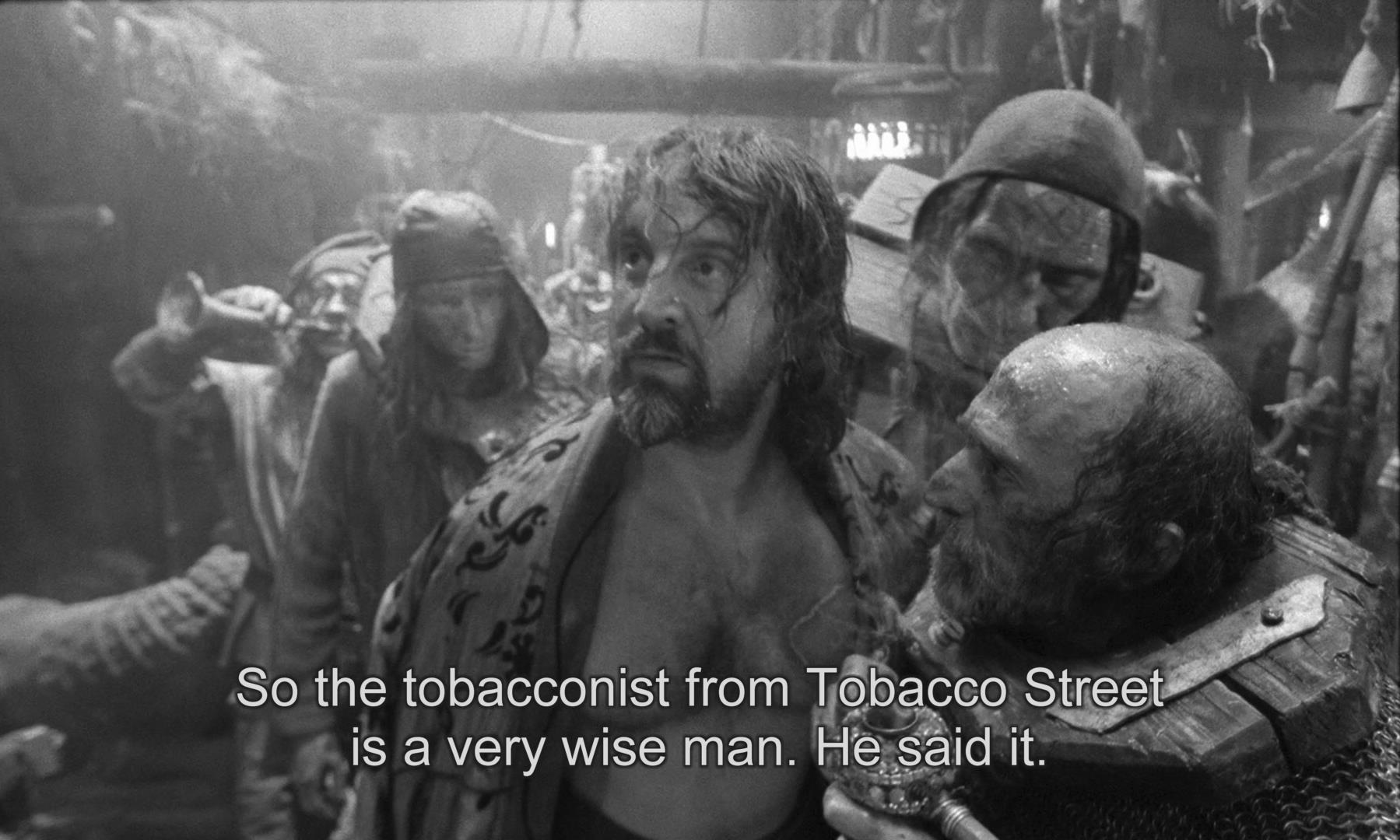

For a while the title of the film was going to be The History of The Arkanar Massacre, partly to

distinguish it from the 1989 version (which German was constantly reminded of because the

news of him going into production on Hard to Be a God in 2000 prompted multiple showings

of the 1989 film on Russian television). I like that title for putting “history” next to a science

fiction name, because that's kind of what the film is in a nutshell. At one point a draft of the

screenplay shows that the title of the film was to be the mysterious phrase, So Said the

Tobacconist from Tobacco Street, which came from one of the film’s half-hidden subplots

about a wise citizen of Arkanar who disappears. I find it an intriguing title, especially keeping

in mind how much of the culture of Arkanar seems to be inspired by Renaissance era Spain,

and knowing that tobacco originated in the Americas. It might allow for a connection to be

made between the film and the history of (and the endless anthropological and philosophical

questions raised by) the collision of the world of Europe with the world of the Americas. Still, I

don’t think you can beat the title of the novel, which the film eventually circled back to.

Aleksei German’s filmmaking techniques put to work on a film set outside of history, have an

incredible effect. The looks into a camera and all that give a feeling of reality for a created

epoch, rather than the recreated epochs of German's other films. My friend whom I saw

the film with for the first time described it as “like a VR tour of Hell”, and I've heard and read

other people describe having similar reactions to the film. The constructed world of Hard to

Be a God has an internal consistency and feeling of authenticity that may be unparalleled in

films dealing with such outlandish subject matter. It’s a triumph of ‘world building’.

So what sort of world has been built? I don't want to get too bogged down in semantic

definitions of genre, but I think Hard to Be a God is such an unusual film that it might be worth

flirting with a bit of cinematic taxonomy.

One word I've seen used to describe the film in a few instances is “Shakespearean”. I'm not

sure it fits so neatly, but it makes a certain sense. Don Rumata can sometimes seem like a

Shakespeare character, with shades of Hamlet, Macbeth, and Lear in his tragic trajectory. It's

difficult to say if those sort of connections are intentional or simply incidental, but at one

point Rumata quotes Boris Pasternak's famous poem, Hamlet, and then takes credit for it.

Taken as a Shakespearean film, I think you could see faint echoes of Aleksei German’s onetime

self-serious filmmaking master, Grigori Kozintsev. Particularly in his adaptation of Hamlet:

And also his adaptation of King Lear:

There may also be a bit of common ground with two other filmmakers who successfully made

Shakespeare cinematic. Namely Akira Kurosawa, with Throne of Blood especially….

The other one being Orson Welles, whose film Chimes at Midnight I remember was brought

up by podcast host James Hancock, when I appeared on the Wrongreel podcast in November

of 2016 to talk about Hard to Be a God...

Still, even with those examples, I think Hard to Be a God isn't theatrical in the way that those

films are, and somehow the tragedy of Rumata comes both grander and far more down to

Earth, as unlikely as that sounds. I'm suddenly reminded of a famous line from Solzhenitsyn's

The Gulag Archipelago, “Macbeth's self-justifications were feeble, and his conscience

devoured him. Yes, even Iago was a little lamb, too. The imagination and spiritual strength of

Shakespeare's evildoers stopped short at a dozen corpses.” In the behind-the-scenes German

doesn't seem as preoccupied with theatrical notions of drama, so much as he is with the

precedent-setting tragedies of history.

I know many of the details in Hard to Be a God have their roots in medieval historicity, with

extensive research in the pre-production process. It captures a rare medieval flavour that most

films set in true the period never quite seem to. An endless filthscape interrupted only by

clean specs of regality and religion. However there are some wonderfully alien touches, that

instantly separate Hard to Be a God from those most medievel films, Andrei Rublev and

Marketa Lazarová, which I invoked in earlier chapters (and maybe also Ken Russell's The

Devils, which is set a bit later than those, but perhaps should be brought up too). Now those

films seem far less comparable to Hard to Be a God than they initially seemed to me. For

instance there’s a religion that closely parallels medieval Catholicism in Hard to Be a God, but

without any analogue to Jesus. It's the only film of that lot that's not dominated with crosses

and Christian iconography. It has only its own strangely-named gods and saints, like St. Gaj. No

Christ, just an inquisition.

So the film is not quite history, but it's not quite 'sci-fi' either. I mean technically it is sci-fi, and

if I’m being perfectly honest, it was the science fiction premise that seduced me into seeing

Hard to Be a God in the first place. It actually reminds me a bit of my favourite episode of Star

Trek: The Next Generation, "Who Watches the Watchers." The episode is about a technologically

primitive alien civilization that has shrugged off religion and superstition, but faces the

possibility of returning to it when exposed to futuristic technology they interpret as

supernatural. The climax of it is the captain, Jean-Luc Picard ready to die just to prove that he’s

not a god, willing to sacrifice himself just to display his own mortality to prevent the aliens

from being plunged back into superstition. Though in Hard to Be a God, the typical concern of

that premise - that an alien civilization may be contaminated through interference - is

inverted. Instead it seems that Don Rumata is the one who is susceptible to contamination by

living amongst the people of Arkanar. It’s a little like Klaus Kinski as Don Lope in Aguirre, the

Wrath of God, becoming increasingly mad as a he travels down the Amazon. Aguirre does not

conquer the Amazon, the Amazon conquers him.

Still, just stating the sci-fi premise is not the best representation of what Hard to Be a God is. It

has no spaceships or anything of that ilk. There are no scenes set on a futuristic Earth to

contrast with life on Arkanar, and it's funny to see internet message board posts from a

decade ago speculating on what fantastical alien flaura and fauna may be created for the film.

There’s nothing that easily dates Hard to Be a God in the way a futuristic space suit costume

would.

There are only a few instances where Hard to Be a God swerves outside of the realm of the

medievel. One is Don Rumata’s sword which is made of a futuristic metal that does not dull

and can slice through anything. Rumata can't resist showing it off to The Baron, getting him to

slice through an expensive chair and attributing it to how the sword was held. Another

example is Rumata's impenetrable white shirt, which sends sparks flying when a knife is

scrapped against it. A child wears to try to save their life near the end of the film, but only end

up strangled instead. There are some sly references to contemporary culture and music too.

Probably the most notable bit of breaking the illusion of history worked into the film is the

tank the Earthlings have, retrofitted to carry all sorts of things, but there’s nothing futuristic

about it. The tank looks old and beat up. Perhaps deliberately on German's part, it reminds me

of the infamous Soviet tanks that rolled through Czechoslovakia in 1968. The same ones that

put Hard to Be a God on hold then.

I should add that even though the film has a timeless quality about it, it’s not quite the film

German would have made in 1968. The most obvious difference would be that it’s at the most

extreme end of his stylistic development, most closely resembling Khrustalyov, My Car!, while

an earlier version likely would have been somewhere in the territory of Trial on the Road.

There are some documented story differences between what the 1968 version would have

been and how the film finally turned out too. For the ending of the 1968 script, Rumata did

not return with the Earthlings as in the Strugatsky’s novel, and did not remain in Arkanar, as in

the current version. German explained, “...people returned to the planet. Another expedition.

This was the ending: some merchants, medieval monks on a modern airfield, and strange

white ships begin to rise and fall in the sky. But I was different then, I believed in some

different things.” Just reading that reminds me of Vincent Ward’s The Navigator, a film I’ve

loved since childhood, renting it from the local library.

Vincent Ward nearly had his own proper grand medieval sci-fi film, with Alien 3. For a while he

was attached to that film as writer/director, and his vision for it involved the monstrous alien

loose on a small artificial planet, panelled in wood, populated by a Luddite-like monastic

Christian order who sought to live as if it were still the middle ages. My favourite scene from

that version, has extra overlap with Hard to Be a God in its scatological overtones; the alien

crawling beneath a series of long drop toilets, and one by one reaching up and snatching

unsuspecting monks, pulling them down into shit and death. Like Hard to Be a God, it was not

just medieval sci-fi, but specifically a sort of Hieronymous Bosch-like vision of medieval sci-fi.

All that would be tossed when Vincent Ward was replaced on the film, with only the barest

structural skeleton remaining (enough to gain Ward a 'story by' credit). I think it’s one of the

great missed-opportunities in science fiction film.

I've already hinted that looking at Hard to Be a God only through the lens of the science fiction

genre can be limiting. Still, there are other sci-fi films that sought to transcend the genre in a

way that lends themselves to being brought up when discussing the film. I don't think Andrei

Tarkovsky was entirely successful with Solaris, even though its the film I thought best to quote

near the beginning of this chapter. One of my favourite anecdotes about pre-production was

the author of the novel, Stanislav Lem becoming increasingly frustrated with Tarkovsky cutting

back on the sci-fi elements of the story, so he sarcastically told Tarkovsky something like “why

don't you just set the whole thing on Earth?” which Tarkovsky took as a brilliant idea.

Tarkosvky wasn't able to go that far with Solaris, but he would with his own adaptation of a

Strugatsky brothers novel, Roadside Picnic. The resulting film, Stalker, stripped 'sci-fi' down to

it barest most mysterious bones. It's become a major cinematic touchstone (is there any

Tarkovsky film that isn't? The last two maybe), to the point where I think that filmmakers are

tempted to directly imitate it. In particular, when adapting the Strugatsky brothers’ stories to

film, you'll often find filmmakers who want to ‘make my very own Stalker’. You have Sukorov

doing Days of Eclipse (which featured Trial on the Road actor Vladimir Zamanskiy) or

Konstantin Lopishansky doing Ugly Swans for example. On one level I like both films, but

there's an awkwardness that comes with their pastiche. Hard to Be a God on the other hand is

the work of a distinct peer, not a fawning imitator. It's comparable to Stalker in that it similarly

strips away the 'sci-fi', but of all the film adaptations of Strugatsky brothers’ novels I've seen,

it's the one that least resembles Stalker.

There's another sci-fi film that isn't quite a sci-fi film, which Hard to Be a God might be

compared to, Polish filmmaker Andrzej Żuławski’s On the Silver Globe. I'm far from the first

person to make the comparison, so I won't go in depth, but I will say I think they're compared

not so much for any specific parallel (though there are a number of them), but more for the

enormity of vision and thematic concerns behind a story of Earthlings on an alien world.

Żuławski and German are similar in many respects, and wildly different in others. If I had to

very broadly characterize the difference between their filmmaking, I'd say Żuławski's film is

like a high-pitched, primal scream, while German's is a low rumble. The sort of rumble that

can quake a mountain.

I should mention too that On the Silver Globe was never completed as intended. The

production was shut down in 1977 with a good chunk left to be filmed. Eleven years later,

Żuławski used documentary footage and narration to cobble together the film in a way that it

becomes in part a documentary about its own mangled existence. So along with Vincent

Ward's unrealized vision of Alien 3, Hard to Be a God seems like it should be the sort of film

that was never finished and would only be hypothetically great, and at various points that was

nearly the case... but there it is, fully realized!

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, for a while German nearly abandoned Hard to Be a God

once and for all of his own accord, because he thought that it would no longer be relevant in

the post-Soviet world. German's opinion on its lack of relevance changed with the rise of

Vladimir Putin. German would say, “Nowadays this has all once again become a contemporary

story.” I think that seeing history facing the possibility of repeating itself, perhaps made

German dig deeper for the thematic content of Hard to Be a God than he had for the previous

unrealized iterations. I suspect that German's goal was to repurpose the Stalanis allegory of

the original story to have a larger scope than being only about communism or Stalinism. After

all, the roots of Russian misery are older and run deeper than communism. Stalinism is a part

of the picture, but Hard to Be a God gets at something more foundational. I think German

wanted to show something universal. Something ineffable and eternal. Other filmmakers have

used science fiction as a vehicle to try to depict things both ineffable and eternal. It resulted in

things like the psychedelic light show that is the climax of Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space

Odyssey. German's concept is radically different. Human fallibility is eternal and history is

ineffable. Muck is infinite.

If Khrustalyov, My Car! is the final word on Stalinism, then Hard to Be a God might be the final

word on Russia as a whole. A poem constructed from the essence of the hard-learned

lessons of history, distilled into a single viewing experience. This is the true Russian Ark. Planet

Russia, floating out there somewhere in space.

“Russia is a nation that never had a renaissance,” German would say in the behind the scenes

footage of Hard to Be a God. The sentence stands out because it’s true; the advancements of

the European renaissance had to be imported to Russia. It’s enough to make you wonder if the

the medieval science fiction world of Arkanar is Russia’s true face. That its soul is still in the

dark ages. That might explain the problems addressed in German's other films. In the same

footage, German singles out the Russian celebration of tyrants as an example of what he's

getting at. He relates a conversation that he had with fellow filmmaker Nikita Mikhalkov, about

how there are no statues of Tsar Alexander II, also called Alexander The Liberator who did

many great things for Russians, while statues of people who were responsible for the death

and misery of so many of their own citizens can be found all over.

German is explicitly weary of the effects of power on people. He'd state (while Karmalita is in

earshot) that if he were in the shoes of a man like Stalin, “I’d hang Svetlana just in case she

thought of organizing a coup.” It sounds unfathomably cruel, but true, which is why he needs

to say it. I think back to The Fall of Otrar, and really Don Rumata’s arc is like seeing Undzhu

Khan become Ghengis Khan. What the character of Rumata is, is to make us recognize in

ourselves our capacity for atrocity. That's some tough love.

When asked about the meaning of Hard to Be a God, Sevetlana Karmalita would insist that, “At

its core, I always felt that it was a love story,” perhaps a little coyly, though not coyly enough to

disregard. I think of a line from the present-day prologue of My Friend Ivan Lapshin, “…a

declaration of love for the people I grew up with as a child”. It may not seem like it, but in that

way perhaps the film is ultimately a declaration of love. At the very least it was a labour of

love.

I want to take the opportunity at this point to say that Karmalita’s script (the final draft of it all

was in her hands) reads like a work of literature, or even a poem, entirely distinct from the

Strugatsky brothers' novel. Here’s an excerpt, translated into English:

Don Rumata of Estor is the one we see at the end of the deadly path. The same snow-white

shirt instead of chain mail and half-armor. The same golden thick hoop with a large emerald

over the bridge of his nose. Only his face is different, total arrogance. He chews a blade of

grass and sits unnaturally in his saddle. Golden Irukansky coat of arms on the harness

complements the picture. Rumata turns his horse around. Somewhere behind, a heavy slap

sounds, and an explosion of happy shouts.

The street ends with the city.

On the corner sits a screamer with a sick. Their throat twisted.

A slave boy in a motley pile.

The screamer is choking on something.

The slave boy beats a drum and rattles bells.

Twilight thickens, absorbing light. At the stone well, a half-naked slave wearing a copper collar

on a chain, chews a cake, thinking about something.

Further low, bushes, swamps and lone dying trees. Rumata rides with his hand on his side, his

chin lifted with his nibbled grass. A ridiculous white puff in this realm of iron and dirt.

Something snaps in the ditch. Rumata ignores it. Then from the ditch, from the rotting bushes

that fluttered with the evening wind, a small fat citizen in a broad hat, in a poor cloak dirty

with mud, in wet pants, with a knot under his arm, goes out onto the road. He takes off his

coat and, after having cleared his throat, asks quite cheerfully:

“May I run next to you, noble don?!”

"You can take hold of the stirrup."

It was quiet. Two birds flew by.

"Who are you?" Rumata asks.

“Tinsmith Kyun ... I'm coming from Arkanar. Trading matters.”

Rumata, like a bird, bends his head to his shoulder.

Keeon, or whatever his name is, peeks out from behind the leather of the saddle, the golden

coat of arms on the harness flashes light onto his bald head, into his eyes. Sweat drips down

his shaking cheeks.

Rumata waves his hand, driving away the mosquitoes.

"You're a book-reader from Tin Street." Rumata puts his finger on a very wet bald spot.

“Running from Arkanar, like a dog?"

"I'm running.” Kyun lets go of the stirrup, to cling to the spur.

Lead actor Leonid Yarmolnik complained that when shooting began, many of his lines would

be cut or altered to change Don Rumata into more of a ‘strong silent type’. German,

overhearing Yarmolnik, had to interrupt the interview to chime in with “Dialogue is for the

radio.”

In a more recent interview, Leonid Yarmolnik mentioned that he had a dozen or so falling outs

with German over the years of shooting, and at one point German seriously threatened to

replace him with another actor, but Karmalita made them reconcile every time. Through the

prolonged shoot, Yarmolnik forged a very close and devoted friendship with German that

continued after filming had wrapped, and until German’s death. Yarmolnik would be one of

the pallbearers at German’s funeral.

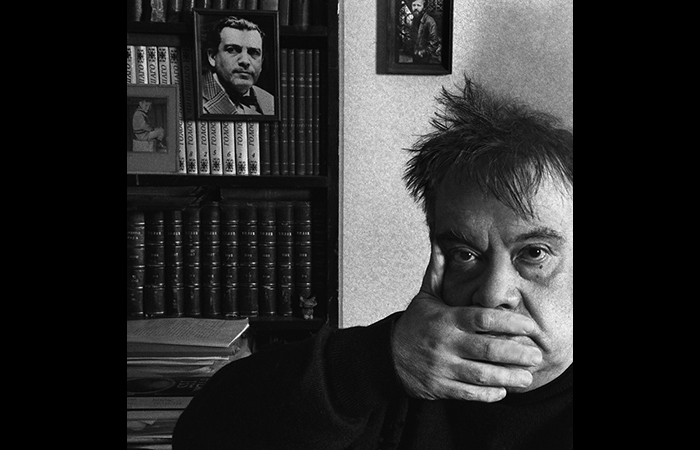

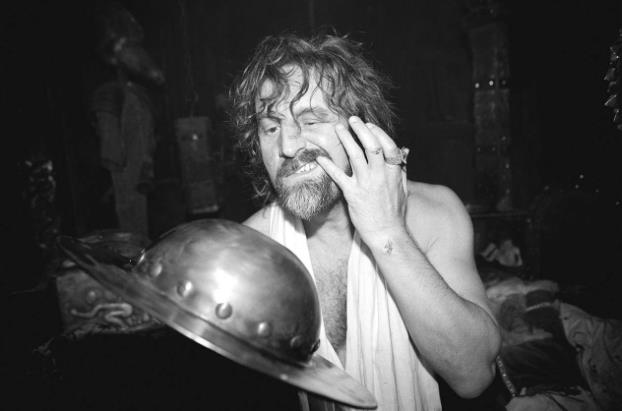

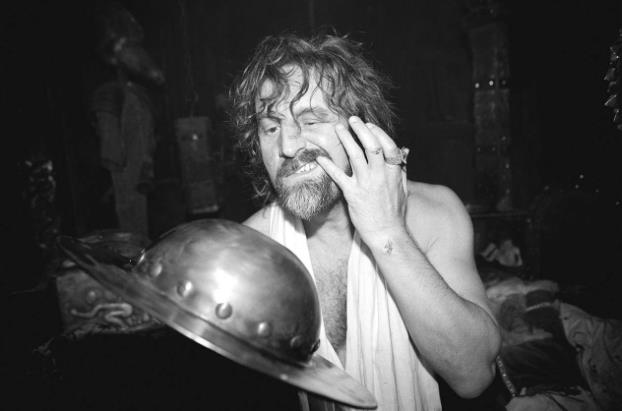

You can see how much of Yarmolnik's life went into the film simply by looking at a photo of

him from costume testing next to a photo of him from the final scene:

It was an incredibly long and taxing production, though not an especially expensive one (even

by Eastern European film standards). A major reason for that is because most of the film was

shot on location where German had always intended. I find it a little funny that for a film so

rooted in Russia, it was filmed mostly in The Czech Republic, with much of its cast and crew

being Czech. German recalled an encounter he had with the bratty filmmaking son of a

famous director, who apparently boasted to German that he would make “a greater film with

more murders” than Hard to Be a God. That would never happen because “I killed all of

Czechoslovakia,” German would say with a laugh.

Most of the film was shot in and around Castle Točník. I was excited to find this out because it

was a castle I was familiar with. It had a sort of Renaissance fair there when I went as a child.

There were people in the castle who were skilled in making armour and chainmail, sword

fighting, and falconry. An ideal place to create a medieval world. It even crossed my mind that

the owl seen prominently in one shot in Hard to Be a God could very well be the same one I

saw when visiting the castle with my parents as a small child. Looking at family photos, I don’t

think it is the same owl though. That would have been too good of a coincidence.

“The Czechs with whom I worked, as it turned out were amazing people,” German would say.

He was pleased to find Czechs with specialized skills like how to safely simulate hanging, or

how to set someone on fire for an extended period of time without harming them. He seemed

genuinely proud of the crew he had to work with. In the behind-the-scenes footage German

would describe his crew as 'great' and 'brilliant' and point out that the prop master was a

former nuclear physicist, as a bit of a brag.

I’m not sure how mutual the feelings were. On the Hard to Be a God episode of The Projection

Booth podcast, film historian Daniel Bird mentioned that while he was working on Juraj

Jakubisko’s 2008 film Bathory, he’d hear stories from the crew about “the mad Russian

director, who shot endlessly”. German began work on Hard to Be a God in 2000, and

production went on and off for about seven years (with another nearly six years in postproductions).

I’m sure German’s process could frustrate any crew. For instance, supposedly if

German wanted snow in a scene, he wouldn’t have fake snow used, he would simply have

everyone wait until the weather changed and it began to snow for real. He was prone to giving

“impossible instructions”. I get that, I mean I've never seen a film in which the dropping of bird

shit was so carefully choreographed and timed.

I think that German needed the film to be perfect. Not in the aesthetic way we usually mean

when we say that a film is “perfect”. Often German's shots are perfect in a way that would

cause most filmmakers to drop the same shot into a trash bin. I mean perfect in the sense that

German needed to put all of himself into every frame of it. To push himself as an artist in a

way that’s like to open his chest so that the audience might see his pulsing heart. Karmilita

described an incident during production when German would not shoot. She said that

everything was set up, everything was rehearsed, but he did not shoot. She urged him to just

shoot something, as he could always reshoot later, but German would not shoot. They wasted

a whole day of production like that. Then a whole second day. Finally, he asked that hundreds

of flowers be purchased. It was an idea taken from medieval history, of using flowers to help

perfume over the perpetual stench. The flowers were incorporated into the scene (and later

throughout the film), then at last German could shoot. It’s difficult to imagine putting a crew

through that, but I think German just couldn’t film a scene unless it had a certain integrity

(maybe especially when it came to unpredictability). I mean when you see it on screen there's

no doubt that he was right about the scene.

When asked in an interview about Hard to Be a God taking so long to make, German just

shrugs in the way that he often does and mentions that it took Alexander Ivanov twenty years

to paint The Appearance of Christ Before the People.

In interviews German seems almost certain that the film would be a commercial failure. The

audiences who had waited in lines to see My Friend Ivan Lapshin were no longer in Russia.

German also spoke openly about how it would be his final film. He had health problems with

his kidneys which persisted throughout filming. Karmalita said that there were days when they

went straight from shooting to the hospital, and the return from the hospital the next day to

continue shooting.

German's original co-author of the script, Boris Strugatsky said in a a 2010 interview that while

he was not a consultant on the final production, he “knows in advance that the film will turn

out to be wonderful and even epoch-making." Boris Strugatsky died in 2012, just three

months before German died, so neither would see the film premier.

German did manage to see Hard to Be a God with an audience though. He had a test

screening for Russian film critics and writers near the end of the film's long post-production.

The initial reactions of that audience ranged from impassive to negative to outright dismissal,

leaving German certain that the film would fail. Apparently though, after leaving the

screening, many of those critics went to a pub to continue talking, and over food and drinks

that night, the tenor of their thoughts on the film took a more positive turn. Film writer

Alexander Melikhov who attended that rough test screening would say, “Aleksei German is a

brilliant artist, able to create images of such power that far exceeds all possible rational

concepts. I do not want to say pathetic words like 'like' and 'do not like'. Can you like the

phantasmagoria of Bosch or the Caprichos of Goya? It's grandiose!”

Thinking that German didn’t live to see the film premiere, it seems to me all the more like a

message in a bottle hoped to be picked up by anyone who will care to look.

Hard to Be a God went on to find greater international success than any of German's other

films. It would also be the first (and at the moment of writing this, only one) of his films to be

officially released on home video in the English-speaking world, with a Kino Lorber blu-ray in

North America and an Arrow blu-ray in the UK. Still, even a few years since its release, it's

difficult to asses what the film's legacy will be. I’ve seen many cinephiles talk about it in the

same way they talk about Salo the 120 Days of Sodom, watching it as a sort of ‘gross-out

challenge’. Or like Satantango, being treated like cinematic Mount Everest to be conquered. I

think those sorts of reputations may generate cult interest, but perhaps inhibit attempts to

understand what those films are about. In other words, a badge or trophy, not something to

be considered and felt.

I don't want to tell anyone how they should watch a film, but I don't take Hard to Be a God as

something to be endured, and instead find it very watchable and rewatchable. It might sound

contradictory (like just about everything else about the film), but for all the misery that Hard

to Be a God expresses, it alleviates something within me in a way that other films don't. Like a

great Blues song that I can listen to over and over again. It fills a lacuna I hadn't fully realized I

had before seeing it.

It’s one of the few films I truly, deeply, give a shit about.

CODA

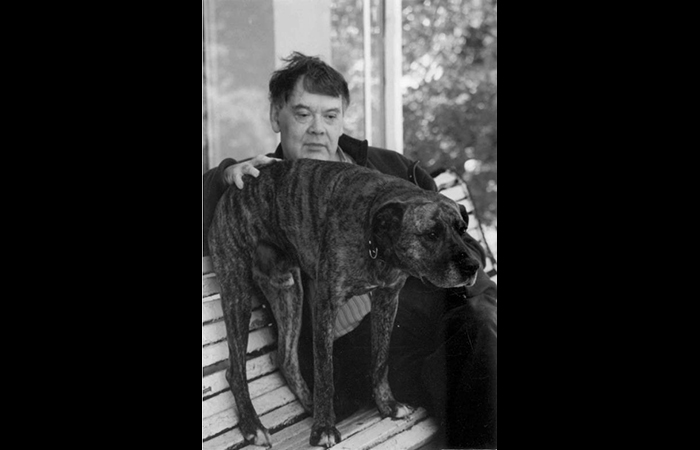

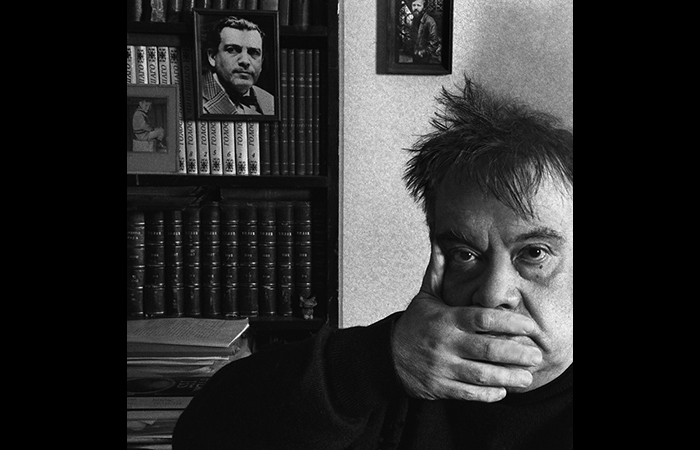

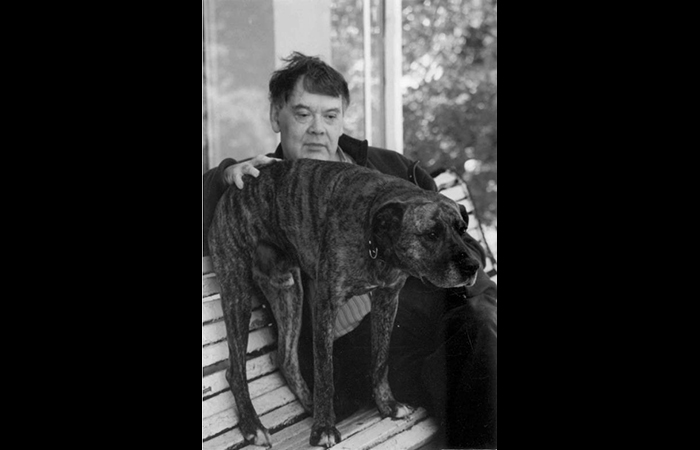

Surely German was the beating heart of Russian cinema. His death was like a star that’s burnt

up and collapsed, but maybe something persists.

After Aleksei German’s death, Svetlana Karmalita continued to be his greatest supporter. I

think that their forty-five year personal relationship is remarkable alone, and their fort-five

year creative and professional partnership is something truly rare and impressive. She

continued to beat the drum, so to speak. I’m forever grateful that she had the strength to

complete Hard to Be a God, promoted it, and see that their work didn’t fall into the dark

chasm of total obscurity.

Svetlana Karmalita passed away in 2017. In her obituary she is described as “Aleksei German’s

moon”. She was half of everything great about him. I think hearing about her death, more

than anything gave me the impulse to write this. After diving in, I found that a number of

German’s collaborators and associates have passed away in recent years. Some even died

while I set about writing this. It left me wondering what if there are aspects of the history of

German's life and films that were at risk of being lost forever.

I originally intended all that I've written for this series to be just a brief career overview, but

the more I learned, the more I felt like I couldn't leave it alone. After finding out abut the care

and thought and passion and life that went into each of German's films, it seemed to me that

it would have been wrong to be slight.

As you can probably tell, the more I explored, the more other films and people and anecdotes

seemed to be drawn in. I could have gone on endlessly, but at a certain point I had to cut

myself loose and drift away into space. Still, there are enough wonders and unexplored dark

corners to entice me to return before too long.

I feel the filmmaker's absence more strongly now than when I began all of this, precisely

becomes he seems all the more present. Aleksei German is like a black hole at the centre of a

galaxy, invisible but keeping everything in place spinning.

~THE END. CONTINUED ONLY IN THE DEPTHS OF ETERNITY~

~ JUNE 29, 2018 ~