NOVELIZATION APPRECIATION

INTRODUCTION: NOVELIZATIONS ARE PEOPLE TOO

Well I've been threatening to do this for a while now, so here it is: the launching of my new series on movie novelizations. I've always been fascinated by these disreputable cash-in media oddities, ever since my days as a movie-starved youngster who would read and re-read the paperback versions of favorite films in the months between their theatrical debut and home video release (I remember specifically reading Rob MacGregor's adaptation of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade three times during one interminable science fair.) I won't take time in this introduction to relate the many pleasures of the novelization, several of them discussed in Grady Hendrix's great article in Film Comment.* I'll try to scatter those across the series as I address a question nobody's ever cared enough to ask: is there any kind of value to be found in movie novelizations?

* It's not online but here's a similar piece he did for Slate Magazine.

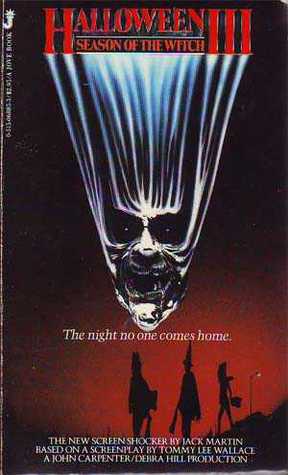

HALLOWEEN III: SEASON OF THE WITCH

by Jack Martin (based on a screenplay by Tommy Lee Wallace)

john cribbs

special thanks to Ian Loffill

The towel fell away from the boy's face. Tears were streaming down his cheeks and blood percolated out of his open mouth. He was hunched over like an old man. See? thought Laurie. Look what Halloween did to him.

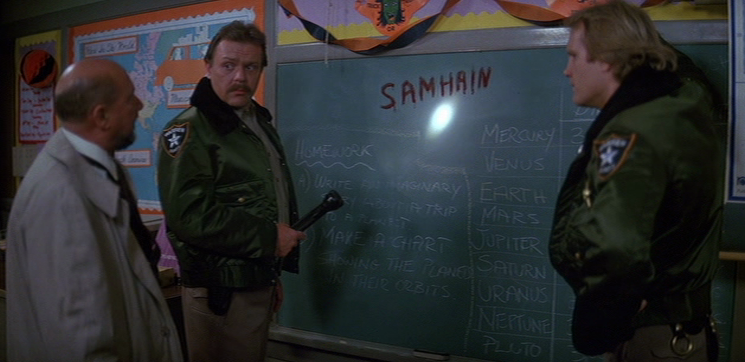

Michael Myers didn't put the razor blade in that little boy's candy. How could he when he was preoccupied breaking into hardware stores, defacing the chalkboard of the local school and snacking on freshly killed dog, not to mention his staring-past-the-wall, post-killing downtime? The night he came home was a busy one for the big guy, and I doubt he had time to leave wicked surprises for credulous kids who, like trusting Tommy Doyle, were under the naïve impression that Halloween was all doorbells and sugar daddies. As the opening credits of Halloween II reveal, there's something beneath the jack o'lantern that's ancient and evil, something beyond human comprehension that has no purpose but to senselessly slaughter and destroy. What, you never heard of Samhain? Druids and sacrifice? Does Loomis really have to take time out of his obsessive Myers hunting and mumbling to give you a lecture on the insidious origins of an unholy holiday homogenized through the centuries until it became a harmless excuse to egg houses? John Carpenter, his producing partner Debra Hill and production designer/protégé Tommy Lee Wallace, starting with the first sequel to their surprise 1978 hit, made a commendable if not entirely successful attempt at establishing an ambiance derived from the malignant nature of All Hallow's Eve's sinister character by portraying an evil even more abstract than the amorphous murder spree of the Shape, the star of what on the surface is a straightforward slasher originally titled The Babysitter Murders. That said evil corrupts the innocent is suggested in the opening scene of the series' first film in which a 6-year-old Myers grabs a knife, dons a mask and butchers his older sister, thus reclaiming the rite of trick 'r treating for October 31st's malevolent founders. However the idea that Myers was spawned from some kind of greater, impenetrable Absolute Evil - while alluded to by a raving Loomis in Carpenter's movie - is subtly introduced in Halloween II (a sequel that makes Myers less mysterious by introducing further family ties and a motivation for him going after Laurie Strode) by the insertion of its seemingly extraneous razor blade scene, which, in hindsight, was a way for the filmmakers to shift focus from their franchise boogeyman to a larger prospect of horror scenarios. Forget Michael Myers, Carpenter and company hint - there's lots of anthologizible evil happening on Halloween, like, say, this tale of druids rigging masks with chips of rock from Stonehenge that will destroy children en masse: one giant transmitted razor blade across America.

Interestingly though, the razor blade scene, which is no more than a kid with a shiny shard of crude steel protruding from his gaping upper lip being hastened to the hospital by his somewhat alarmingly composed mother, didn't appear in the theatrical print or subsequent home video releases of Halloween II. This cut (nyuck nyuck) makes sense when you consider the scene has nothing to do with the narrative - the pair end up at the same pediatric ward as Laurie but are presumably discharged long before Michael Myers arrives to carry out his unfinished business - although another explanation for its excision might have something to do with it being a "a vile and gratuitous bit of evil," in the words of Harlan Ellison.* Whatever the official reason, for several years, until the scene was reinstated into the movie on dvd, the only place this scene existed was in film's novelization, written by Jack Martin. Not only is the unlucky tyke part of the narrative (in the film he's just kind of there), he serves as a sick reminder to a near-traumatized Laurie that unconscionable evil is a part of the world that has to be faced; the realization rejuvenates her for a time. Novelizations can provide background that movies don't have the time or the correct tools of expression to communicate the way a writer can in a book, and they anticipated the Halloween series' move to more specifically Halloween-based mischief well ahead of the films themselves. Curtis Richards wrote original novelization, which apparently expands on the holiday's dark background.**

Richards' book opens:

The horror started on the eve of Samhain, in a foggy vale in northern Ireland, at the dawn of the Celtic race. And once started, it trod the earth forevermore, wreaking its savagery suddenly, swiftly, and with incredible ferocity.

Wow - and here I thought the horror started with Sam Hain, Judith Myers' boyfriend, trying to cop a feel of her foggy vale in suburban Illinois before her parents got home or her little brother stabbed her to death (whichever happened first.) Poetic license is the leisure of novelisers (either because the studios who commission them demand a certain flourish to the writing or, more likely, don't care) and Richards uses the prologue to relate the sad tale of a 15-year-old disfigured boy named Enda who, in a fit of passion, murders King Gwynwyll's daughter Deirdre and is thereby doomed to have his soul walk the earth forever searching for bodies to possess so that he can endlessly reenact his brutal crime. The book goes on to explain how the awkward Myers boy becomes host to this ancient spirit, reporting in detail his murder of Judith and subsequent evaluations by Dr. Loomis. In the Halloween II novelization, Jack Martin continues the development of Myers as having a supernatural origin prior to surviving six piddling bullets to the chest in the first chapter, using the film's characterization of Loomis to further this idea:

Loomis cocked the hammer with both thumbs and sighted at the mask. It had been raised only an instant, but long enough to reveal the inconceivably bland, emotionless features of a face free of any feeling, a creature so devoid of any recognizable human expression that it was capable of absolutely anything. It could as easily tear the arms and legs from a human being as from a fly, with no inner restraints, conscience, guilt. No hesitation. No consideration of the consequences, and no remorse. NO CONSCIENCE. A perfect killing machine, a pure and simple alien ego devoted entirely to its own subhuman purposes. It had not been born of man and woman - through them, but not of them. An imposter in humanlike form, a simulacrum catapulted here across generations of evolution from the dawn of prehistory to subvert and destroy the accomplishments of an entire species.

Tell me that's not exactly what Loomis was thinking when he saw Michael Myers' face. Suggesting that Myers hails from "the dawn of prehistory," whether it's Richards' disfigured druid boy or something less palpable, seemed to open the floor to new ideas. "Indeed," Carpenter later said of the series, "there were no more stories to tell. All you could do is what Friday the 13th did, which was to repeat the action sequences and make them gorier. I was trying with Halloween III to expand the concept, make it like there were different Halloween stories to tell. But the audience hated it and everybody got mad at me because they thought I destroyed their franchise." Carpenter wanted to use the series to "give young directors a chance to make their first film and maybe want different stories." The first young director he approached was Joe Dante, fresh off The Howling, who in turn recommended old writer Nigel Kneale to handle the screenplay. Carpenter was a fan of Kneale, a legend across the pond for his creation of the iconic Professor Bernard Quatermass and his four serialized adventures (the first three adapted into feature films by Hammer Productions), so even though Dante ended up moving on to Gremlins the Manx writer was commissioned to do a treatment. Kneale quickly came up with an idea, essentially re-working a serial he'd written about a TV signal that makes teenagers commit suicide called The Big Big Giggle (which was roundly rejected by the BBC who feared real-life imitations) into a story of a crazed Irish toy manufacturer with a similarly outrageous scheme. The deranged mogul ships out Halloween masks fitted with a sliver of Stonehenge (part of which he's managed to smuggle to the states; funny, since Myers' murders in Halloween are preceded by the removal of a stone from its place in the earth: Judith's tombstone) from his home base in a small California town which, not unlike Quatermass II's Winnderden Flats, has been taken over by the villains and is patrolled by robotic armed guards from the factory.*** When activated by a subliminal flashing light on the Silver Shamrock ads, the chips cause mask wearers to literally bug out (that is, their heads melt and snake and insects emerge from their skulls.) Humanity's only hope is a successful yet down-to-earth common man, a familiar Kneale staple representing what Quatermass IV director Piers Haggard referred to as the "tremendous re-assertion of the importance of people, ordinary people, and how necessary they are in fighting evil." Other similarities between Kneale's script for Carpenter and Quatermass II are the Halloween III baddie's habit of taking over good people's bodies (Ellie), the hero meeting a tramp who knows more than he should (for his part, Carpenter would let the homeless get their revenge by becoming the murderous goons in Prince of Darkness, then by becoming the heroes who crush the conspiracy in They Live) and an unbearable hick family, complete with obnoxious son, who are executed (almost comically) by the bad guys. Funnily enough, the most Kneale-like inclusion - the evil power coming from the transported Blue Stone of Stonehenge - was not from Kneale's draft, even though only three years earlier he had supernatural forces harnessed from the powerful Stonehenge-ish Neolithic site Ringstone Round killing children (and a dog) in his fourth and final Quatermass serial.

Carpenter and director Tommy Lee Wallace (possibly at the urging of distributor Dino De Laurentiis) took a shot at making Kneale's script less talky and more thrilling. They brought some of their own references to the story, most of them from Invasion of the Body Snatchers. They set the story in the same fictional town (Santa Mira, California - changed from Kneale's Sun Hills) and rewrote the ending so that it reflects and pays tribute to Siegel's film, with the hero running around trying unsuccessfully to warn people of an inconceivable threat to the world, after the love interest has had her body "snatched" and replaced, in Halloween III's case by a murderous robot (more on that later.) Like Miles Bennell the leading man is a doctor, consequently he's never able to get any sleep: he's disturbed trying to catch some z's by the discovery of a murdered man in the hospital, later in a hotel room he complains about being seduced when he just wants to sleep. "I see this film as more a 'pod' movie than a 'knife' movie," producer Debra Hill once remarked of the series' transformation, and she's right - it's almost a missed opportunity that they didn't cast Kevin McCarthy as the conniving Conal Cochran (I say "almost" because Dan O'Herlihy is great in the role.) Carpenter and Wallace's movie also references the previous Halloweens, complete with a tagline - "The night nobody comes home!" - that plays beautifully off the original's while seemingly raising the stakes for its characters and an opening scene of the killer stalking his prey in a hospital much like Halloween II. At the same time, there was a clear distancing from what had come before: it seems almost subversive to replace the unquestionably evil Myers with a bad guy so giddy about his outlandish plot you're almost rooting for him (just compare Halloween III to another Carpenter sequel, Escape from L.A., which ends with a worldwide act of wanton terrorism that is perpetrated by the anti-hero rather than the villain.) In another subtle stab at de-powering the Shape and his lust for dominant killing, Nancy Loomis, throttled to death as victim Annie Brackett in Part 1 and whose death was verified by wheeling out her corpse in Part 2, appears alive and well playing Challis' spirited ex-wife (amusingly, in real life she later became the ex-wife of Tommy Lee Wallace.)

But it wasn't just the ditching of Michael Myers that made the next addition to the series different. The Halloween gang didn't just want to tell a different story, they wanted the series to grow up a little. The first movie takes place in schools and neighborhood streets and involves pranks and pumpkin carving - even the killer starts out as a kid. Part II's hospital setting is more grown-up, but presented as a place where young people shouldn't have to find themselves at the twilight hour: its weirdness is based on teenage Laurie (and to an extent the young EMT Jimmy) being out of her environment in this sudden adult world; the setting's changed, but it's still seen through a "young" perspective. Halloween III takes it in a whole new direction: it's not a movie about teenagers made for teenagers, it's about adults facing the threat of terrible violence against their children, whereas the parents were notably absent in the first two installments. The transition from 'knife' movie to something else meant a new attitude for the series, and the least successful elements of HIII have to do with Carpenter and Wallace trying to recreate the world of the film to fit this new mold. Obviously, any attempt to do so was just going to be confusing to the series' audience; at the time, Wallace stated "It is our intention to create an anthology out of the series, sort of along the lines of Night Gallery, or The Twilight Zone, only on a much larger scale, of course." That this decision probably should have been made before the release of a direct sequel with the same characters that picked up the exact same place the first movie left off apparently occurred to no one. For his part, Kneale, famous for being cranky, outspoken and generally dissatisfied even before he was old and bitter, had this to say: "I wrote what I thought was one of my best scripts. If they'd done it the way I wrote it, it would have been a good film, no question." So there was no chance that Kneale, who had novelised all four of his own Quatermass stories, would be handling the Season of the Witch novelization.

That duty, as with Halloween II, fell again to Jack Martin. Martin is in reality Dennis Etchison, the excellent fantasy writer/editor whose much-anthologized story "The Late Shift" first appeared in Kirby McCauley's seminal collection Dark Forces and has gone on to became one of the most recognized short works of the late 70's/early 80's horror fiction boom. It also appeared in the author's The Dark Country, its cover bolstered by the oft-attributed blurb "Etchison is one hell of a fiction writer! - Stephen King." "Jack Martin" is actually the protagonist of the eponymous award-winning story, an uninspired artist on a joyless vacation at a Mexican beach resort. Having already set himself apart from events at the dismal locale, Martin spends the second half of the story as a practically nonexistent observer, watching as his friend and other American tourists cover up an awful crime that occurred late the previous night. It's Martin's disengagement and indifference as he observes this gruesome spectacle that makes the brilliantly moderate narrative so unsettling. So maybe that's why Etchison used the name to write his novelizations: he wanted a certain amount of detachment from the material while possibly acknowledging that he, like aloof and impotent artist Jack, wasn't 100% into the assignment ("Dark Country" isn't written in first person, so the extent of Etchison's personal identification with Martin is debatable.) Not to suggest that there's nothing worthwhile to be found in his take on Halloween III (see next page), but although Etchison is a hugely respected author of short stories, half of his novels are novelizations, suggesting that it's in short fiction that he thrives (and he really does: just check out the the last sequence of "Dark Country" where he writes about the death of Karl Wallenda, it's breathtaking.) According to Etchison, the novelizations took "around six weeks each" to write (as opposed to the 1 1/2 to 2 years it takes him to write an original novel) and his ultimate motivation for writing them came from a professional relationship with Carpenter,**** for whom he had previously novelised The Fog (under his own name), that resulted in an offer to let Etchison take a crack at an original script for Halloween IV. Etchison is a Native Californian, which made him ideal to adapt The Fog and Halloween III, both specifically California-based (the third Halloween didn't try to pass for the midwest like the first two entries) and the Halloween III job provided him with a challenging lead character whose head he could break open to see what he found inside. That, and one giant razor blade.

* Ellison's rant against the movie and other horror/thriller/slasher/"knife kill" movies of the era, featured in the collection An Edge in My Voice and mentioned before by me on this site, received a responding letter from a defensive horror movie fan who called the writer out for either "lying or...criticizing films he has not seen" for mentioning the razor blade scene. Ellison fires back by correctly insisting the scene existed in the pre-release print he saw before being edited out by producers who "may have had a momentary spasm of good taste and excised it, thereby denying you (the author of the letter) a moment of pleasure," although his description of the scene itself ("kids bite into apples filled with razor blades") isn't really what happens.

** I would have loved to have read it for this article, but it's one of the few novelizations that's considered something of a collector's item and is hard to come by cheaply. My most-wanted novelization is Phantasm, written by Don Coscarelli's mother, romance novelist Kate Coscarelli. It is seemingly impossible to track down: the only copy on Amazon is currently going for 300 bucks.

*** It's also reminiscent of the island community of conspiratorial druids in The Wicker Man.

**** They apparently bonded over the coincidence that Etchison had just published a story called "White Moon Rising" and Carpenter was working on a script for the movie Black Moon Rising, a largely forgotten Tommy Lee Jones-Linda Hamilton-Bubba Smith movie about a super spy car.

<<Previous Page 1 2 Next Page>>

home about contact us featured writings years in review film productions

All rights reserved The Pink Smoke © 2012