MOVIE SHELF: COMPARING FILMS TO THEIR LITERARY COUNTERPARTS

JEAN LUC GODARD'S MADE IN U.S.A.

based on the novel THE JUGGER by RICHARD STARK

Welcome to Movie Shelf, a series that compares the films on our dvd shelves to the novels on our bookcases. We at the 'smoke have always been fascinated by screenplay adaptation: what a script writer takes from the original source material, what he changes, how the two different works vary from each other and what the existence of the movie itself says about the book and vice versa. All this and more will be examined in this ongoing line of articles.

THE ABSOLUTE RULE OF MORALITY: Jean Luc Godard's MADE IN U.S.A. v.s. Richard Stark's THE JUGGER

"Is killing fewer men than war the rule we live by?" - Paula Nelson, Made in U.S.A.

The first Hunger Games movie opened last weekend to unsurprisingly stellar box office,* once again prompting the question "Is there anything more boring than a best-selling book series turned into a gigantic hit movie series?" It's the film business at its laziest and least creative: there's no risk involved whatsoever, the adaptation is a cut-and-paste job, but it's guaranteed to make money because everyone and their mom's entire book club is familiar with the source material or are huge Lenny Kravitz fans. I don't bring this up just to dig at The Hunger Games - I mean, what's the point of that? But the age-old practice of transitioning audiences from buying copies of wildly-popular novels to purchasing tickets for wildly-popular movies has, in my mind, made even the success of such approved classics as The Godfather, The Exorcist and Jaws seem all the more unimpressive. They lose some of their luster stuck in the same category as the John Grishams and Da Vinci Codes and The Helps that keep hogging the screens** where a more venturous experiment might find an audience. A real audience, not awkward chat room acquaintances or flabby office co-workers who come out complaining "Well in the book his vest was blue, but in the movie it's green, and I just found it very hard to adjust to that!" Ok, now I'm just being ridiculous: obviously, how the written word is translated to the cinema experience is something that compels us all, hence this series dealing extensively with that very subject. Even keeping the safeguard of a director's artistic license and the fact that we're dealing with two completely separate forms of media in mind, it is difficult to get past areas where the filmmaker slipped up and missed the tone or the character of the book, or cast the wrong person in a pivotal role that's so embedded in the reader's brain from the author's indepth descriptions. Rare is the perfect union of actor and literary icon (although Chris just wrote an article about one such case of ideal casting - no, I don't mean Nora Dunn.)

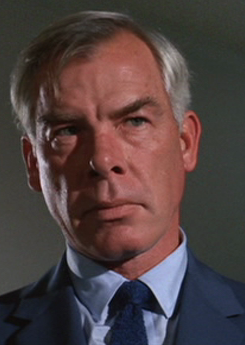

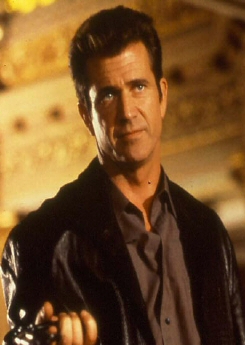

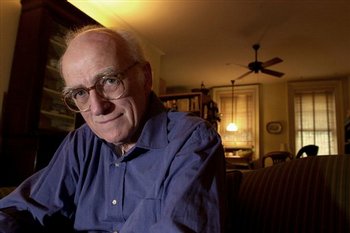

When it comes to Parker, professional thief and amoral anti-hero of 24 novels written between 1962 and 2008 by Donald E. Westlake under the pseudonym "Richard Stark" most fans agree that a spot-on cinematic surrogate hasn't yet been realized. Although seven adaptations have been sourced from the Stark novels, the Parker character - the name always changed since Westlake refused to hand it over, anticipating an as-yet unproduced series of Parker movies a'la the James Bond franchise - each one fell short of capturing the remorseless bastard from the books. In Point Blank, Lee Marvin's almost spectural Walker is placed among a surreal setting of late 60's San Francisco. The motive for Bobby Duvall's Earl Macklin in The Outfit (for my money, probably the best of the movies) is a personal quest for revenge, which anyone who's read the books knows is hugely uncharacteristic. The Split's Jim Brown and Slayground's Peter Coyote weren't bad choices - those movies just aren't very good - and while it's a noble effort, 1999's Payback*** just couldn't scrub Mel Gibson's inherent movie star smugness and general likability from a man who's supposed to be awash in apathy. Westlake readers go back on forth as to which one came closest to the spirit of the books, but all tend to agree that the very first Richard Stark adaptation, Jean-Luc Godard's Made in U.S.A., made in 1966 (in France) was furthest from the mark.

Crooks and books were the bricks in the wall that made up Golden Age Godard: it isn't a rare sight in any of the films from the first and most enduring stage of his career to see someone holding an open book in one hand and a gun in the other, which they would then use to awkwardly turn pages. Made in U.S.A. opens with Anna Karina's Paula Nelson lying in bed with a book titled Adieu la vie, adieu l'amour... (the French translation of Horace McCoy's Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye), a gun resting at her side that will be subsequently tucked between the pages of another book. The narrative of these films stop cold - or, in Made in U.S.A.'s case, have to wait to begin - as entire passages are read aloud by gangsters, kidnappers, revolutionaries, amateur heisters and existential murderers, detectives and femme fatales. Godard's own personality was largely based on being a studied intellectual and well-read bibliophile, and I always wondered how he managed to read so many goddamn books when he was busy averaging three movies a year between 1960 and 1968. The answer came from none other than László Szabó, the male lead of Made in U.S.A., who I met when he taught an acting course at SUNY Purchase.**** He explained to me that the legendary rebel of the Nouvelle Vague would often read only the first ten, then the last ten pages of a book before discarding it. I mention this not to discredit Godard, only to better access Godard the adapter. Because the narrative he borrowed from novels and short stories were often just frameworks, hollowed out and replaced with the director's own obsessions; appropriately, one such novel called Obsession (a book by Lionel White, another American crime writer) shares only a surface resemblance to Pierrot le fou. There was never room left for the source material's pulp-infused contents: appropriately, later in Made in U.S.A., Karina tries to jam a gun into the perfectly carved-out center of a book, but it doesn't fit.

Made in U.S.A., as an adaptation of Westlake's The Jugger, is usually renounced by people like the folks over at The Violent World of Parker as having only its first and penultimate scenes resemble the book at all. While these two scenes from the movie correspond closer to the actual chapters in Westlake's book than anything else, sharing dialogue and even close-enough character names, upon closer analysis there's a lot more from the book interspersed throughout the film's narrative. Not to suggest that Made in U.S.A. has anything but a perfunctory relationship to its source matieral: it's as tangible to Richard Stark as Contempt to Alberto Moravia or Le Chinoise to Dostoyevsky (although those would also be worth exploring in an article, as would the relation of Weekend's 8-minute traffic sequence to Cortazar's "The Southern Thruway.") Godard fans argue over the Foucauldian implications of the film while relegating the book to a footnote; Westlake admirers want to know why Parker's a lady and why the most violent gunfire is employed against a wall with words written on it. We here at the 'smoke are fans of both Godard and Westlake (just look at what we named our kids ferchrissake*****), and as such I thought I'd take a stab at finding some kind of commonality between these two works, especially since Westlake's work has endured past his death three years ago, certainly moreso than American mystery writer Dolores Hitchens, whose Fool's Gold (basis of Band of Outsiders) is long out-of-print.

The Jugger, the sixth book of the series, has Parker traveling to the fictional town of Sagamore, Nebraska to pay a visit to Joe Sheer, the retired jugger (safe cracker) who now lives a quiet life under an assumed name and funtions as Parker's "answering service" - whenever someone wants to get a hold of Parker for a job, they go through Joe. Parker's received some worrying letters from his liasion begging for help, which anyone who knows Parker would never expect from him and therefore wouldn't request in the first place. Since Joe knows all about Parker's legitimate identity as "Charles Willis" - the name under which he owns parking lots, laundromats and pieces of property to document on his federal tax forms - Parker can't take the chance that Joe's going soft or senile and might give it all up: he arrives in Sagamore ready to kill the old man if he has to. But somebody's already done that for him - Parker arrives just in time for the funeral (which of course he doesn't attend.) The circumstances of Sheer's death are suspect, with the coroner and funeral director covering up for a corrupt local lawman named Abner Younger who, it turns out, has been shaking Sheer down to find out where all the loot he's amassed over the years is stashed. Parker plays along, partnering with Younger under the pretense of helping him find the money that Parker knows doesn't exist, so he can eliminate all ties between himself and Sheer. But things go wrong, and in the end Parker is forced to abandon the "Willis" identity, leaving behind thousands of dollars of hard-earned heist money and essentially having to start from scratch.

As far as I can tell, The Jugger isn't a fan favorite. Westlake himself even had mostly negative things to say about it, although that may have been before the book was rewritten for future publications. In the first printing of the story, Parker's motivation in sticking his neck out was to try and help Joe - Westlake correctly decided that was a little too kind for his heartless heister. I can see why fans of the series wouldn't like it: it's really different than the other books, mainly because there's no heist - there isn't even any money, although most everybody but Parker thinks there is. He's on his own for the first and last time since the beginning of the series, The Hunter, and he really screws up in the end, making a bad judgment call that costs him big time. But those are all reasons it's actually one of my favorites of the Parker books (to date I've read all but the final six.) For one thing, as cool as the preparations and actual heists of the series are, it's refreshing for Westlake to have tried something different with the character. A more intimate story, it sheds off the slickness of some of the capers Parker finds himself taking part in and focuses on Parker's weaknesses rather than his strengths, and is therefore a little more realistic. Because of that, it has weight. There are consequences. Innocent parties get interested, their involvement gets them killed, and for nothing - Joe's horde of cash is an illusion, a romanticized notion of the retired outlaw. Such a naďve assumption helps make Younger a more involving character: he's motivated by greed, but he's also complicated, not just a one-dimensional backstabber or competitor.

In a lot of ways he's like Parker, but his small town mind is no match for his enemy's experience. More a sadist than a levelheaded heister, he pathetically sets out to rob an old man (Westlake even goes out of the way in the book to mention how Parker never robs individuals; not out of sentimentality, institutions just mean a bigger payoff) and his very American craving for quick riches is just a pipe dream. But then Parker also hatches an incorrect theory about Younger, a mistake that costs him his legitimate identity and lots of cash (two books back Parker allowed himself to be blackmailed thanks to a gun with his fingerprints on it, and in the next book he basically gets his whole crew killed by stepping out for a coffee when he's supposed to be guarding the money, but this still goes down as his biggest blunder.) Jugger is also a lot more "noir-ish" than most of the books, really emphasizing Parker's toughness - 20 pages in he's already knocked a man to the ground 3 times and locked a naked woman in the bathroom - and his sexiness (unless I'm misremembering, Parker notably smokes more in this book than in others.) Maybe readers find all this out of character with the rest of the series, but again I think it's a nice departure.

All of this probably meant nothing to Godard when he picked up The Jugger, titled Rien dans le coffre, or "Nothing in the Trunk" in France (I can't think of any specific scene this relates to in The Jugger: nobody ever checks for the money or hides a corpse in a car trunk or steamer trunk or anything - I doubt it's a sexual euthanism, however they are French...but why would they want to criticize Parker's boney butt? No, I guess it's just a reference to there being no money "in the trunk" - that would make the most sense, right?) Since the movie was released a year after the book, the version Godard read must have featured a noble Parker worried about his troubled old friend only to find him dead and feel compelled to avenge him rather than a pragmatic Parker ready to kill Joe if it means protecting himself. Which is significant as far as the director's decision to transform hard-as-nails criminal Parker into adorable journalist Paula Nelson, investigating the death of former lover and prominent leftist Richard Politzer in a provincial town brazenly referred to as "Atlantic-Cite." Her conflicted emotions over Richard's death make up the core of the film: forced to avenge his death as a social justice when her political leanings are romantically humanistic, she makes for an idealogical contradiction, namely evil (murder) in the name of good.

The frustration was Godard's own, Made in U.S.A. a vessel for his barely-concealed anger over the disappearance of Mehdi Ben Barka, "Morocco's Che Guevara," a political exile in France abducted and allegedly tortured to death by French police.****** Specifically, Godard imagined a scenario where Georges Figon, a career criminal who was set to testify against high-ranking Moroccan officials in connection to Barka's disappearance before he too died under mysterious circumstances, had a mistress who, responding to a letter from her former flame only to learn of his death, decides to find out the truth and avenge him. A romanticized version of a story that's essentially about a man whose motivation is to kill anyone who can put him behind bars, made all the more interesting when you consider who's telling it. Westlake was famous for the novels written under his real name, comedic caper adventures and darkly funny tales of reluctant and/or incompetent criminals. His good spirit and humanity is evident in the work, always entertaining and effortlessly able to explore seedy topics without being morose or cynical. Westlake relied on the "Richard Stark" persona to create a somber, unsympathetic character his naturally compassionate narratives could never conceive. Meanwhile Godard, a cynical, mean-spirited malcontent, did the exact opposite by utilizing adorable, charming Anna Karina in dire scenarios brightened by the presence of Karina and a skillfully enlivened aesthetic to match her sunny disposition. Eventually, Godard's contempt won out and his films became increasingly humorless and less interested in entertaining the audience - Made in U.S.A. is not only part of that turning point, it's an active transitioning mirrored by Godard's real-life separation from Karina (more on that later.)

The obvious conflict here is that you couldn't find anyone less like the soulless Parker than sweet-cheeked Anna Karina, or as comfortably laid back. In the early books, Parker is in constant movement from the very beginning. The first line of The Outfit: "When the woman screamed, Parker awoke and rolled off the bed." The first line of The Mourner: "When the guy with the asthma finally came in from the fire escape, Parker rabbit-punched him and took his gun away." Even The Jugger starts with its protagonist mid-action: "When the knock came at the door, Parker was just turning to the obituary page." Made in U.S.A. opens with Karina's Paula Nelson lying leisurely on a bed, her first line is: "Happiness for example. Whenever he desired something, so did I." She's questioning the symbiotic implications of a relationship: she wasn't happy unless he was, or desired anything unless he did. She had no needs of her own, leaving her with no personality...like Parker. Except that she's in love. Parker never thinks about love when he's on the job - that comes later. Even in The Jugger, where there's no actual heist taking place, he still staves off the aggressive advances of a young lady so he can keep his mind on the business at hand, then comes back for her later. Paula's still thinking when the whiskey arrives: at least she and Parker share a love of booze.

And they both hate cops. Although it goes without saying that Parker would never ask what color shoes go best with his outfit, even as a ruse to bludgeon the other guy over the head with the heel. Parker's no talker, whereas Paula talks constantly, even to a stoplight; in fact, when two toughs give her the silent treatment she's the one who implores "Please say something to me." Exact opposite of Parker, who'd also never play "eenie meenie miney moe" to pick a weapon (the Stark novel I just finished, Backfire, even contains a stretch of dialogue about how Parker doesn't leave anything to chance.) Interestingly (and most likely a coincidence) Paula has a little piece of narration after bumping into an old enemy: "Fortunately I'd dyed my hair black. Korvo didn't recognize me as the blonde from Agadir." So she's altered her appearance to avoid people from her past, kind of like Parker having his face changed at the beginning of The Man with the Getaway Face. They even share similar dialogue here and there (U.S.A.: "Now tell me things I don't know."/ Jugger: "Tell me something I don't know.") But let's be honest, there's really nothing much to connect the character of Parker to Paula Nelson - it's the differences that reveal more about Godard's version of Westlake's creation. Anna Karina's recurring role for Godard was the suppressed, unliberated soul who found it impossible to connect with her emotions: most famously she played this sort of victim for him in Vivre sa vie and Alphaville. Godard's intentions in those films was to emancipate the Karina character's mind to the possibilities of truth and love.

If these are concepts, the constructs of which are contradictory to everything that distinguishes the character of Parker, that Godard honestly cares about, the impersonality of Parker couldn't have possibly appealed to him. Wouldn't Godard hate Parker, the emotionless brute who speaks in action rather than thoughts, his personal reflections a locked cage the reader is never privy to? Wouldn't such an unethical criminal embody the late Richard Politzer's words on the tape recorder, read by Godard: "bravery without risk and pride without sacrifice"? Is he not "mean" like Godard's hated Right? For what it's worth, we meet Paula at her most Parker-esque, having moved away from her once strong political convictions as she has the man who obviously awakened them in her - she's more world-weary and ideologically defeated, and is drawn back to defend her former beliefs only out of a nagging devotion to her former lover. She doesn't really have anything to fight for other than misanthropic inclination towards revenge, and as such she has no reservations against murdering someone on her own team if it means her survival, something Parker is committed to but isn't required to actually do; if Godard really did read an early version of The Jugger where Parker wanted to help Joe rather than kill him, he could have actually beaten Westlake/Stark to this pessimistic resolve, unknowingly tapping into the Parker character more than it seems. Parker's stoicism is also in line with Godard's direction of actors: impassioned speeches are read in blank-faced monotone, the banal dialogue muted, the important speeches disembodied; emotionally high movie moments such as love scenes and bursts of violence are purposely under-played, although this is hardly unique to Paula. The thing Parker (in The Jugger) and Paula most have in common is that everybody's against them in a place they're not familiar with: they each enter the town as a stranger and it's dangerous - even Joe, a risk-taking safecracker who's performing daring heists across the country, found himself powerless in this seemingly quaint burg. Joe was as successful and hardcore a heister as Parker, but had lapsed into the sentimental "happily ever after" life of a retired homeowner and become vulnerable, his survival instinct replaced with the trappings of contentment. For Richard it was the opposite: sticking to his political ideals have made him a matryr to his cause.

* Recently I've been more conflicted than ever when it comes to the movie business. Considering the decline of video stores and hard media over the last few years, I'm now genuinely concerned about the future of movie theaters. So on the one hand, I find that I'm honestly excited anytime any movie does boffo box office these days - as long as there's money to be had, you have to figure the big screens are safe and not everybody prefers to just sit at home and watch shitty bootlegs on the internet. But how am I supposed to be excited about the success of The Lorax, 21 Jump Street or The Hunger Games? Soulless Dr. Seuss adaptations, TV show rehashes and predictably huge tie-ins to a mediocre young adult series of books...how can I root for these things in good conscious and complain about them at the same time?

** It seems like they make a movie from every mildly-popular book these days: no sooner had I set down Michael Faber's Under the Skin when I found out Jonathan Glazer had just finished the movie.

*** The 2006 director's cut is better than the theatrical version, mainly because Gibson's "Porter" is a lot less sympathetic and even kills some people in cold blood a'la Parker (who in the book accidentally kills an innocent woman but doesn't really care.)

**** László was an amazing person to chat up: he had acted in films from all five of the main founders of the French New Wave: Chabrol, Rivette, Rohmer, Truffaut and Godard. His debut for Godard was as the wounded man who runs into the cafe, shrieks "Les yeux!" and dies on the bar in Vivre sa vie, after which he turned up in most of the director's early films: a lead role in Le petit soldat, the part of chief engineer of the Alpha 60 in Alphaville, a brief appearance as a political exile in Paris in Pierrot le fou and the garbage man alternatively speaking for his black brother and eating a loaf of bread in Weekend. One day at Purchase, László casually mentioned meeting Godard for dinner in the city, leaving those of us listening with the tantalizing aside "I'd let you come, but I haven't seen him in a while and would like to catch up."

***** Chris' son is named Parker, my daughter is Odile. It's a good thing neither of us are Tom Robbins fans. If Chris has another kid, I hope he names him Salsa.

****** Barka was supposed to meet with Georges Franju the night of his disappearance to discuss plans for a documentary, another New Wave tie-in.

<<Previous Page 1 2 Next Page>>

home about contact us featured writings years in review film productions

All rights reserved The Pink Smoke © 2012