MOVIE SHELF: COMPARING FILMS TO THEIR LITERARY COUNTERPARTS

john cribbs

JEAN LUC GODARD'S MADE IN U.S.A.

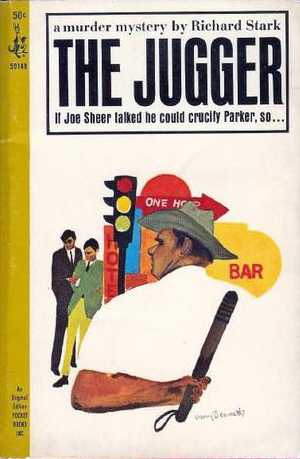

based on the novel MADE IN U.S.A. by RICHARD STARK

page 2

It's appropriate that Richard is the one missing in the movie, since "Richard Stark" is largely left out. Godard has cited the influence of Howard Hawks' The Big Sleep on the film, and both heroics and villainy are decidedly more Humphrey Bogart than Philip Marlowe. The hardboiled nature of American crime fiction isn't something that necessarily interests Godard: something gets lost in the translation, although he acknowledges a respect for "second-rate thrillers" by naming the movie's eager writer "David Goodis." Goodis spends his screentime working on something he calls the "unfinished novel" - doesn't that describe the Parker books or any other crime fiction series that keeps going until the author dies? The template for the Goodis character in The Jugger is a girl who would technically be designated Parker's love interest, a throwaway sexpot as disposable as the squeeze Parker left behind in Miami, but since Goodis is something of a phantom presence in the background of the story, always thinking and writing with limited contact to characters other than Paula, he's also a stand-in for the memory of the deceased Richard. Divorced from the narrative, working on a perpetual story (a'la the Parker books) by literally translating the events of the movie to his own prose-heavy style, David/Richard is a way for Godard to connect to Stark/Westlake on screen, the director effectively taking the story of The Jugger, reworking it as a Godard film, and then assigning a character the task of reworking it into an "unfinished novel" WHILE THE MOVIE IS HAPPENING.

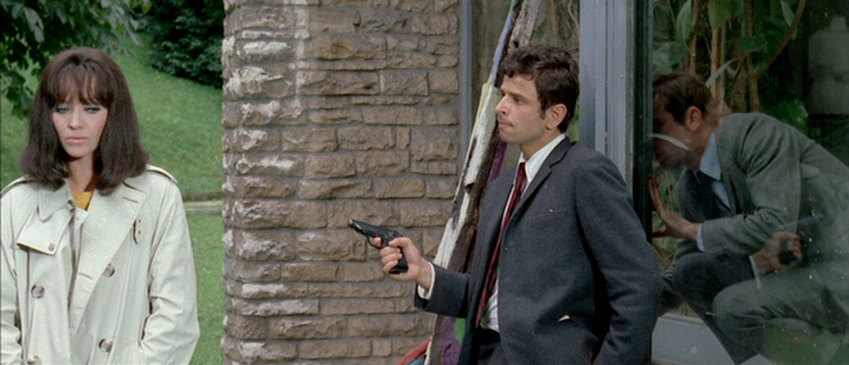

It could also be a way to filter some of Stark out: David's fluffy prose is pretty much as far as from the Parker books' sparring, straight-forward style as you're likely to get, almost incomprehensibly pretentious as opposed to simple and blunt. But as the two styles clash against each other, aspects of Stark do make their way to the surface. László's Paul Widmark is a stand-in for the Younger character, a corrupt cop who's playful but dangerous, his first line of dialogue a Mel Blanc/Sylvester imitation, his intimidations delivered as he's playing a pinball machine. Jean-Pierre Léaud's naturally boyish persona makes him the surrogate of a nosy young neighbor from The Jugger, whose death (killed and buried in a basement by Parker) occurs at about the same point in the story as Léaud is gunned down by Paula in Made in U.S.A. (Godard gives Léaud a little toy to play with to make him seem even younger and more blissfully unaware of what's going on around him.) Léaud's characer is named Donald Siegel, kind of funny since the name is specifically "Donald" not "Don," even though I don't think Westlake had yet been outed as Stark (citation needed!) If "Paul Widmark" had the correct name of "Richard," the two heavies - one soft and playful, one seasoned and genuinely dangerous - would be "Donald" and "Richard." Instead "Richard" ends up as the murder victim while Paul Widmark, Paula Nelson and a minor character "barman or Paul" are also weirdly connected by their similar first names. The only one that matches up with a character from the book is the squirrely, Rosario Vaina-esque "Tiftus," renamed "Tyfus" in the film. Other connections to the book are subtle, but they're there: Paula muscles her way into the morgue/lab to see Richard's body, just as Parker somewhat strongarms his way into the funeral home/doctor's office. Paula is knocked unconscious investigating an address around the same time Parker is knocked cold doing the same thing. The Tyfus/Tiftus character is mysteriously killed in Paula/Parker's hotel room leading to a subplot involving another cop who sets it up so the companion of the murdered man is passing by Paula/Parker and can shout "That's the one who did it!" (and a following scene where Paula/Parker speaks to the companion while they're still in police custody, although Godard shuts out the dialogue, which leads to the witness withdrawing their accusation.) Paula sets them on the trail of a dead man as suspect and the outsider cop is taken off the Typhus case. The structure is actually incredibly close to the book, although the motivations are political. Although Donald is described as not believing in "secret documents or in political mysteries - he only believed in money," Widmark needs Paula not as a key to unearthing a stash of cash but rather to find out where the evidence that he killed Richard is.

Although his previous film had been Masculin/Feminin, which predicted the May 1968 protests that (temporarily) collapsed Gaullism and the Fifth Republic, the aftermath of Algerian independence and slippery practices of French democracy as represented by Ben Barka's disappearance were what inspired the restless atmosphere Godard tapped into for Made in U.S.A.Barka is mentioned in the film, as is the 1961 Charonne Metro Station Massacre (Godard even drops a Kennedy assassination conspiracy theory, although he's careful to point out that Le Monde is the source for that, even citing the date of the article to make a clear distinction between levelheaded political science from paranoid speculation that is so often murky in the director's work.) It's hardly an extreme supposition that Godard equated French occupation with American foreign policy and foray into Vietnam. The thing that is "made in USA" is shady intrigue and violent political incursion, leading to the conclusion that any infiltration by a superpower into foreign territory, no matter how true the intentions, naturally leads to unrest and violence. The parallel is Paula's investigation into Richard's death, herself a stranger who enters a politically tense environment trying to change it for the better, the morally unresolved detective who, through the process of solving a crime, brings about further disorder in the reckless pursuit of justice. Paula's response to Marianne Faithfull's unaccompanied, acapella version of an already ambivalent Rolling Stones song, where the subject is content to "sit and watch," is a lengthy aside that sums up the film's key theme: "Whatever I do, I can't escape from my responsibility for others. They are affected if I say nothing, or if I speak. They are bothered if I leave, or if I stay. They are lost if I don't care about them, or if I do. If I am trying to be considerate, sometimes inconsiderably so, it can be fatal to them." The moral dilemma of involvement - to do nothing about an injustice and allow it to continue, or take a stand against it only to institute the same methods of terrorism and torture - is to choose, as Paula states, "to exist to become increasingly present."

In The Jugger, Parker can't help but become increasingly present, to effect other people, even though his very purpose is to stay unknown by protecting his front. But when he makes himself known, specifically when he's after something (usually money somebody took from him) like in The Hunter, The Outfit, The Sour Lemon Score or Butcher's Moon, more people die and the destruction mounts to a degree that criminal empires are crumbled within days. Parker knows this and makes his own decisions, as stated in one of my favorite lines from any of the books, which comes after he learns that Younger knows his real name: "Parker looked up at him, seeing him definitely for the first time as a dead man." But since he lacks the introspection of Paula - he can't see that becoming involved with Sheer's murder just makes things worse for him and results in more people getting killed (three, to be precise; Godard ups it to five.) Ironically, it's making himself visible that makes him...well, visible, and rather than walk away anonymously he's now linked to his crimes. Paula has to decide to be present, to be seen, to be culpable. On the flip side, Younger/Widmark want these things, like an actor pretending to be a tough guy in a gangster movie, and both their respective reward is to be unceremoniously annihilated. But the consequence of Paula's decision towards action is that she has to see it to the very end, which includes murdering the innocent David Goodis, so much collateral damage for the justified avenging of Richard's death. That the leading lady now kills the charming male as opposed to obliquely giving him up a'la Breathless is the act of a Godard more intent on placing responsibility solely on the militant who put everything in motion - let no mistake be made, Paula has accepted her role. "By choosing death rather than a life without meaning," she sadly realizes, "I am gauging my existence against the...absolute rule of morality."

Godard and Westlake compensate for their lead character's immoral inclinations by granting them absolute convictions. Paula and Parker, although acting out of nothing but their own interests, share a steely resolve that makes their actions, however deplorable, justified - vindicated if not exactly condoned. This balance is maintained by contrasting their methods and motivations to those of the story's ostensible villain. Interestingly, Godard presents the unconscionable act of torture in the narrative, yet the main part of the book he leaves out is Younger's "oblique method" of tormenting Joe. The structure of many of the Parker books is to lose Parker entirely, usually around the beginning of the third act, and focus on another character by backing up the narrative to the point where that person became involved in the story - in The Jugger, that person is Abner Younger. Having stumbled upon Joe's criminal past, Younger sets out to first break his victim down psychologically, making himself known to Joe wearing full uniform without telling him what he wants. The indirect suggestion of punishment/imprisonment that Younger initially presents is soon obscured by the more insidious threat of invasion that his presence in Joe's life brings: he's the ultimate bully, rendering his elderly target as pitiful and helpless as possible until he has no choice but to submit any control over his own fate. This feeling of ultimate frailty leads Joe to suicide, since nobody dies of old age in the world of "Richard Stark," a constant and uncompromising contest of physical supremacy (note the name "Younger," although it is explicably stated that he's 51, probably to establish his background as a war veteran - not exactly young, but nearly 20 years Joe's junior.)

There is an implicit level of physical torture: once Joe is dead, Younger worries that "If the death was a suicide, there'd be a routine autopsy, and the first thing the doctor would see would be the marks Younger had made on Sheer, the bruises and burns, the cuts and rope marks, the whole history of what Younger had done to try and pry the half million out of the stubborn old bastard's carcass." A pretty harrowing passage, but light compared to the level of subjective assault Westlake describes Joe having to go through. Godard only implies the use of torture through photographs of Richard being killed and the sight of his grotesque corpse, presented as a skull wrapped up like a mummy with such recognizably human features as wide eyeballs, teeth and flakes of tissue still intact to make up an expression of horror. The torture of a woman by Widmark and his gang to get information, which Paula finds "disgusting", occurs like Richard's death off-screen and visually referenced in a brief shot of the bandaged, a reflection of all that was left of poor Richard in the morgue. The casting of László, who played the taunting FLN torturer in Le petit soldat, and of Karina, the ultimate victim of fatal torture by French intelligence agents in that same film (the first one László and Karina did with Godard; both were also in Vivre sa vie, which was released first) are themselves references. Their characters are described as "Moroccan War" vets, undoubtedly an allusion to the moral ambiguity of the Algerian conflict but more notably a way for Godard to politicize his "little soldiers." Although they have their own version of war stories - my favorite moment in the book is where Younger demands Joe tell him all about his days heisting, and over the course of relating them Joe betrays a fondness for these memories, which Younger alternatively finds himself captivated by ("In some strange way it was a good afternoon, one of the best either of them had ever lived.") But they're not actually soldiers: in a parallel between the two men, Joe was heisting during WWI and Younger, even though he was active, spent WWII serving in the States. As an American, Westlake most likely equated military service to heroism and honor and therefore kept his anti-heroes anti-army, but for Godard, enlistment is a more an ethical grey area of which terrorism and torture are inherent aspects.

By turning Westlake's story into "a political film, a Disney movie with blood," Godard inevitably overloads it with some of his more oblique critiques in a characteristically over-reaching fashion, his tedious "woolly pretention to political anaylsis" (as Geoff Andrew refers to it) that would become so greviously prominent in his post-Weekend filmography. Like the over-long instrumental interludes in Marx Brothers movies, these didactic asides weigh the movie down, even when the director employs fun tactics like "censuring" Richard's last name with the roar of airplanes passing overhead and other random bursts of ambient noise, something he took from Buñuel's Diary of a Chambermaid.* Godard also borrows from Buñuel a notable repetition: László and Léaud standing outside a car waiting for Anna in the hotel, then getting back into car and out of it again in hopes that she will see this "tough" entrance. This kind of rehearsed macho posing both a parody of intimidating officials and a comment on the western films that inspired the movie. In applying a leftist/Maoist/communist/anti-capitalist agenda, making critical parallels to U.S. foreign policy isn't quite enough, so Godard expands his fault-finding net to include the globilization of American culture. If democracy is a polite form of mass assimilation, surely Coke ads are a subliminal device to get everyone to want the same thing: fascist conformity that will die out "like surfing, mini-skirts and rock music," right? Paula even states that she left her newspaper because she believes advertising, exemplified in the film by images selling American movies, is a "form of fascism."

The obvious conflict for Godard is his love of American culture, especially American movies. Made in U.S.A. probably has more references to movies made in the U.S.A. than any of his films: Widmark & Siegel, Inspector Aldrich, Preminger Street, an overhead page for King Vidor's Ruby Gentry (there's also a girl named Mizoguchi, possibly an attempt to keep the references universal, more likely because the character is Japanese.) The film is even dedicated to Nicolas Ray and Samuel Fuller - "A Nick et Samuel, who raised me to respect image and sound." This is as much a send-off as a tribute: even those unfamiliar with Godard's gushings over his favorite American directors in his writings on film know that Pierrot le fou includes a wink to Johnny Guitar and features the Fuller cameo with his most famous quote about film and battlefields. There seems little reason for Godard to once again bring up his love of these filmmakers whose work he helped canonize unless it was the long goodbye, the big sleep for his admiration. Godard was at a point in his career when he was getting vocal about rejecting homages and references - as he was becoming more political academic than storyteller, he was forced to weigh his arguments against American influence in Europe with his love of Hollywood movies. Sure, he was still name-dropping The Searchers in Weekend and casting American actors in his films as late as the early 70's, but the presence of giant cut-outs of American movie stars feels more oppressive than nostalgic. Godard's love-hate relationship with the American cinema has never been more apparent, having gone from waggish (deliberate amateurism in genre set pieces like sloppy musical numbers in A Woman is a Woman and Pierrot le fou, awkward gunplay in Breathless and Alphaville) to dismissive. Needless to say, the inclusion of two minor bad guys named Robert McNamara and Richard Nixon sort of spoils the fun of picking out the names of favorite filmmakers.

Made in U.S.A. was developed and produced quickly, even by Godard's standards, and the movie's murky mixed messages may be attributable to that fact. When you think of Alphaville, for example, the institutions Godard denounced were just as opaque, but since it was steeped in science fiction it was easy to focus on the ideas rather than real-life correalations. Godard recycles a lot from his earlier film: Lemmy Caution also posed as a journalist (named Ivan Johnson, which just happens to be a popular weapon of choice for Parker), comes to a strange place searching for a missing political figure, gets into a violent confrontation in his hotel room at the beginning of the film and also investigates a swimming pool, like Paula looking absurdly out of place in his trenchcoat (the movie could even be considered the promised "adventures in America" sequel to Band of Outsiders: Odile is now Paula - traveling under a fake name, like Parker - Franz the deceased Richard.) But Alphavilleis a fictional place, the U.S.A. is not. Godard seems to realize his ideas are all over the map: Paula and Widmark's hoot-n-holler session as they simultaneously present their respective thoughts and ideals to the audience suggests that the conflict between left and right thinking is frivolous overlapping with no clear "winner."

Even more than usual, Godard stands these characters against solid walls and traps them in interiors to give an idea how limited their views are: when Widmark is killed, it's when he's standing in front of a window with his assassin in plain sight directly behind him - he never would have thought to simply turn around and look behind him, he's so used to being backed up against the solid enclosure of a wall bright painted one of the bright primal, patriot colors of France. Paula herself is just as misdirected by her own lost cause that she allows herself to be led around a large garage in a childish game of "hot and cold" seeking something she isn't even aware of. The frisky, flirtatous nature of Paula and Widmark's political rivalry suggests that we're not supposed to take it seriously, at one point he tells her, "If you swore on Lenin's complete works that it was sunny outside, I wouldn't believe you unless I'd seen it myself" (a reworking of a line from the corresponding scene in The Jugger.) The confusion of political ideas in Made in U.S.A. stems from Alphaville's first line, from Borges, that sometimes reality is too complex for oral communication (also the Maoist maxim that appears as graffiti in La Chinoise: "One must confront vague ideas with strong images") and I guess I'd be willing to give Godard the benefit of the doubt, if it wasn't for retrospect as to where his career would go from here. The later visual essays/experimental meditations did declare some sort of woolly conviction that was clearly Godard's, so if Made in U.S.A. was his way of trying to sort out the mess of messages I guess it didn't take.

What all this has to do with The Jugger is that The Jugger was, of course, made in U.S.A. If Godard wanted to use an American novel to dump his opinions of American culture, it would make sense for him to do something subversive to it like, say, emasculate its hard leading man and make him a woman. The fact that the superfluous character is "David Goodis," an American crime writer who is the last to be cruelly executed, was probably not lost on Westlake, especially coming after the murder of "Donald," both by Godard's lady-fied version of Westlake's creation. It's here that Godard returns to the David/Richard duality: Paula arrives seeking Richard, uncertain of her feelings, and when she "finds" him by proxy she kills him. The dead character discovered only to be murdered a second time, like Terry Lennox in The Long Goodbye (ultimately killed in a foreign land by a detective) and Joan Frost/Lee in Cronenberg's Naked Lunch(killed in a foreign land by a writer) punctuates an apathetic lead character finally accepting their previously shakey convictions and taking control of their actions. Paula had previously stated that "Finding out why Richard died was to find out why I should stay alive," and her rejection of the pseudo-Richard's "truth" is her way of moving on, both from the relationship and her romantic notions of his leftist ideals.

This conviction leads to a great epilogue, probably my favorite Godard ending. Like in The Jugger, the last we see of the hero/heroine is them driving off in a car: Parker with no money or place to go, Paula to an uncertain future lacking any ideology to hang her hat on, starting over at "The Left, Year Zero." Rather than despondent, she's relieved: a liberated liberal enjoying the movie's first sensible and intelligent political discussion with an old friend, the drive itself liberating after all the confining camera angles and restrictive interior sets that have come before. She's suddenly disinterested in her book on Lee Harvey Oswald: paranoid political assumptions have given way to thoughtful analysis. The Jugger doesn't end at a superb moment, when everything is going right, but Made in U.S.A. has that feel. There's sadness, but it's still hopeful - she's so flippant about what she had previously been willing to kill for, it's like she left her beliefs back on that endless tape of Richard (Godard) reading political speeches. Paula asking "Am I the murders I committed?" is really Godard asking "Am I the films I make?" The scene feels like Godard is ready to abandon his self-serious leftist views in a refreshing resignation, apparently accepting the narrowness of critical thinking and humanistic ideals through politics. Just as Parker has left his fake identity behind and resolved to begin from scratch, Godard is declaring a fresh start: no more pontificating and boring audiences.

Of course it turned out the opposite was true, right after this Godard would launch into a period of extreme leftism at the expense of innocent fun and set him on a course to punish his audiences for expecting even a hint of classic movie entertainment. No more crime thrillers, no more adaptations of American novels. Bring on 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her...sigh. What Godard was really doing was saying goodbye to Anna Karina,** this epilogue a serene aftermath to the crime of Godard murdering his muse. Because really Made in U.S.A. is a break-up movie, with Godard casting himself as the absent Richard, subsequently allowing himself to be shot in the head by Karina as a way of casting off "old Godard" (the fact that the David character is introduced wearing the same kind of striped robe as Belmondo in Breathless should not be lost on anybody.) It's a farewell to his love of American movies, which he may have felt lost in the departure of Karina - that would explain the more formal 'adieu' of Weekend. It's here that that lyrics of "As Tears Go By" seem relevant, Godard's frustration over "Doing things I used to do/They think are new," which goes with Odile's line from Band of Outsiders: "All that is new is, by that fact, automatically traditional." For a minute, Karina almost looks back, achingly nostalgic, but she stops herself, prepared to dive into the next tedious phase "exhausted before I start." The development of the director's career from this point is the ultimate betrayal of the line from Le petit soldat: "The time of reflection is over. Now begins the time of action." For Godard, it was definitely, wincingly, time for reflection.

Addendum.

The first Parker-related movie since Payback is due out later this year. Not only are they using the name Parker, the title of the film itself is Parker. I have no idea if it's an attempt to start a series, if it's based on any of the books specifically*** or if they're just pilfering the name. It's easiest to assume the latter, since Westlake wouldn't allow any of the movies made while he was alive to use the name "Parker" (the only time he's ever allowed it was shortly before his death, when he gave his blessing to Darwyn Cooke to produce the extremely faithful, kind of great if unabashedly worshipful graphic novel adaptations of the first few Parker books.)**** The director is Taylor Hackford, whose name doesn't register much confidence. It's hard to write him off entirely since he directed the vastly entertaining if infinitely hokey Blood In Blood Out (a.k.a. Bound for Honor)...but the rest of his filmography, which includes the ballet v.s. tap dancing 'n defection Baryshnikov vehicle White Nights, Oscar darling/Warwick Davis-featuring biopic Ray and one of the more generic Stephen King adaptations, Dolores Claiborne. What's his toughest movie, The Devil's Advocate? He took one of the toughest noirs of all time, Out of the Past, and turned it into Against All Odds...yes, the one with the Phil Collins song. Based on that, and the Lionel Ritchie single from White Nights, I hope he at least hires somebody else to choose the soundtrack. Anyway, Jason Statham is Parker...I guess the British-ness isn't a dealbreaker considering the character's already been a woman, a black guy, a Frenchman and Mel Gibson, but does any actor really earn the right to be the first official cinematic Parker? If not Lee Marvin, then who? Talkbackers are already complaining about things like Statham wearing a cowboy hat in on-set photos ("Parker would never wear a cowboy hat!") so it looks like the controversy of the adaptation is starting all over again.

* The first film of the director's second French period, which ends on a series of jump cuts believed to be a mockery of the playful New Wave style. Buñuel had criticized the Nouvelle Vague directors for preaching against fascism while blithely ignoring the country's history with it during WWII. Applying this signature New Wave technique to a mob of supporters for high-ranking right-leaguer Jean Chiappe (who played a role in banning L'age d'or in 1930) in Cherbourg, of all places, was Buñuel's own teasing way of reminding them.

** Made in U.S.A. is often erroneously referred to as the last project Godard and Karina did together. They actually worked together once more, for the short "Anticipation, ou: l'amour en l'an 2000" Godard made for the World's Oldest Profession compilation film. His treatment of Karina in that short film feels like disastrous break-up sex: vile, resentful and humilitating. If nothing else, Made in U.S.A. - especially its final scene - is at least a classy ending to their professional relationship, which is probably why so many people forget the "Anticipation" short.

*** Imdb lists the story thusly: "Parker turns down a job offer to pull off a jewel heist, he narrowly escapes with his life. [Because he turned it down? Why?] He then teams up with a female real estate agent who is familiar with the local town and has nothing to lose to find the target of the heist so they can steal the loot for themselves." He teams up with a real estate agent? Played by Jennifer Lopez? I can't even connect this to Parker's personality. The screenplay's by John J. McLaughlin, who wrote Man of the House and Black Swan - no real promise there. Michael Chiklis - who is the most appropriate supporting cast member, so far as I can tell - plays someone named "Melander," a character from Flashfire but other names (Ross, Kroll, Norte - the movie version of Salsa?) don't ring a bell.

UPDATE: I've now read Flashfire, which is clearly the book they've adapted for the new movie. I can see its appeal to the producers: it has the same Parker-gets-screwed, Parker-comes-after-guys-to-get-his-money-back scenario as the ever-popular The Hunter (also the basic set-up of The Sour Lemon Score and Butcher's Moon.) Unlike most of the books, there's a semi-romantic interest in the aforementioned real estate agent (although she and Parker never get it on), Parker gets to play "cool" by disguising himself as a slick Florida playboy who drives a fancy car and there are no less than three sets of people who are after him throughout the novel. I can already see where changes will most likely be made for the movie (example: Statham and J-Lo probably will get it on), but I hope they keep my favorite part of the book where, at the beginning, Parker has to pull off a bunch of petty heists that are typically beneath him because he needs cash quick.

**** Cooke's a huge fan who even added an out-of-place Parker-type character to a famous noir-ish Catwoman story he wrote and illustrated.

Related Articles

<<Previous Page 1 2 Next Page>>

home about contact us featured writings years in review film productions

All rights reserved The Pink Smoke © 2012