tanukis, gatling guns and nostalgia:

STUDIO GHIBLI AT THE JBFC: PART 1.

page 2

POM POKO

Speaking of weird fundamentally Japanese perviness, here's a film about magical raccoon testicles. Yes, the testicles themselves are magic: they expand, transform, warp into fake bridges, hang-gliders, assault weapons and ornate boats packed with treasure. If you watch Pom Poko, you will laugh and marvel at raccoon testicles. That is a fact. So, wait, what? What is Pom Poko about? Well, it's all there in the full Japanese title which translates as "Heisei-era Tanuki War Pom Poko." It's about some tanukis (the aforementioned shape-shifting, profoundly testicled magical raccoons) at war during the era ruled over by Emperor Heisei. The only part that doesn't make sense is the "pom poko" tag that was used as the U.S. release's full title. The phrase is an onomatopoeia that represents the sound these tanukis make when the puff up their bellies and bang on them like a bass drum. I think we can agree that simply calling it "Magic Raccoon War!" would have been both more intelligible and more awesome. The film is fairly off-model for director Isao Takahata, who tended towards a kind of stylized realism with his three other Ghibli films My Neighbors the Yamadas, Only Yesterday and Grave of the Fireflies. While frequently championed as one of the greatest achievements in the history of animation, Grave of the Fireflies nonetheless can be difficult to endure - it's based on an autobiographical book about a boy and his young sister braving war-torn Japan. Over the course of the film, the girl slowly starves to death. Only Yesterday concerns a young office worker looking back at her life and regretting her mistakes in love and career. The experimental My Neighbors the Yamadas is a gentle visually stylized consideration of mundane domesticity. It wasn't exactly in his wheelhouse to make a movie about mythical raccoon creatures who morph into forms ranging from teapots to human beings to faceless demons or beat police officers to death with their massive nuts. In fact, Takahata has said on multiple occasions that Pom Poko is his film least close to his heart. The story goes Takahata want to make a film of the classic "The Tale of Heike" about a noble novice samurai set in the 12th century, but Miyazaki pushed him to make a film of the story that had popped into his head one day about tanukis battling real estate developers. As I mentioned in the intro, Studio Ghibli has recently been insistent on giving Takahata his due and placing him on an equal plane with Miyazaki - stories like the genesis of Pom Poko make it a little tough to believe that's exactly the case. Takahata did start out collaborating with Miyazaki while at a level of success and notoriety slightly above his colleague, having directed the well-regarded Horus in 1968 before they joined forces in the t.v. industry in the 70's. But after Nausicaa Valley of the Wind's success that led to the formation of Studio Ghibli, Miyazaki clearly ran the show. After all, how else could have Miyazaki forced Takahata to follow up the acclaimed Grave of the Fireflies not with a story of his own preference, but a tossed-off idea totally out of line with the rest of Takahata's work? The young Heike and his famous story appear in a brief cryptic scene shoehorned into Pom Poko, more or less proving that Takahata's passion for the project is more than rumor. He wanted to animate the tale so much, he jammed it into a film in which it has no reason for appearing.

That isn't to imply that Pom Poko bears no relationship to the totality of Takahata's work. In general, Takahata has a tendency to be a more adventurous and experimental than Miyazaki with far less of a concern for plot. Miyazaki builds driving narrative engines; he uses plot in a way dissimilar from best of Hollywood blockbusters, thrill-rides as it were. Takahata's Ghibli

films are episodic in nature, they tend to have a "this happened, then this happened, then this happened" structure arranged under a loosely conceived over-arching plot. Yesterday, Grave, Poko and especially Yamadas assemble a series of individual scenes and sequences that aren't concerned with pushing their meandering stories forward towards their final destination. As a result, there's a refreshing freedom to by found in Takahata's stories, even a baffling digression

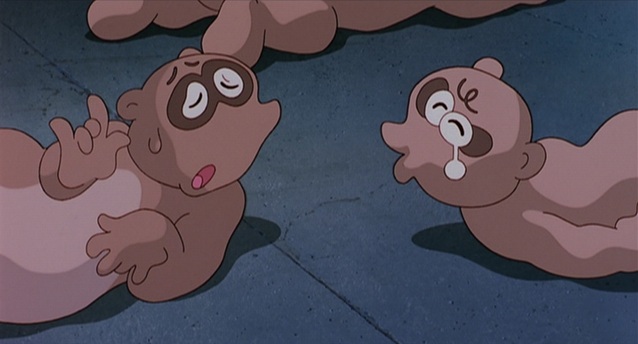

like the Heike interlude in Poko not feeling entirely out of place because the pieces are placed so idly. This looseness extends further to the variety of stylization and the improvisational qualities of his animation - when each section functions in almost a vacuum, there's lots of room for Takahata to try on different stylistic hats and find a visual expression for the moment-to-moment personality of the film. In Poko, the depiction of the tanukis take on three basic styles, depending on the situational

appropriateness - they're introduced in a realistic, biologically accurate version of the animals; once we get to know them a little, they start to appear in an anthropomorphized version that finds them transformed into chubby cartoons who stand on their hind legs and wear little outfits; and finally they sporadically appear as flat, almost featureless caricatures I've read are based on a popular comic book take on the critters (but the hell knows if that's true, Mr. Wikipedia... if that is your real name.) The freedom to swing wildly from realism to comic book style is something that wouldn't work in a Miyazaki film where the stories rely on a cohesive whole - if Pazu in Castle

in the Sky changed in appearance from scene to scene the way the lead tanukis shift in style, it would undermine the world Miyazaki is building and knock you out of the story's flow. Takahata's episodic tales and stylistic experimentation work in codependency, it's difficult to imagine one working without the other. The variety of styles on display don't just extend to the tanuki, but Takahata's fondness for small interludes done in the style of ornate woodcuts, for example, or the mid-film parade

of yokai that faithfully reproduces traditional depictions of the folkloric creatures. There are sequences in the film illustrating the daily grind of a Tokyo commuter without imagistic hyperbole as well as cartoon-y brawls featuring Looney Tunes-esque violence between the chubby, bug-eyed elastic humanized versions of the magic raccoons. It all plays and you never think twice about it. I should also mention that Takahata's films share a certain grimness - obviously, a small child dying of malnutrition

in Grave is no joke, but even the sweet Only Yesterday features a young woman plagued by anxiety about things that happened when she was 10. Pom Poko's climactic piles of the dead raccoons (done in the realistic style) and the tanukis' ultimate defeat leave the film with dark undercurrents.

That isn't to imply that Pom Poko bears no relationship to the totality of Takahata's work. In general, Takahata has a tendency to be a more adventurous and experimental than Miyazaki with far less of a concern for plot. Miyazaki builds driving narrative engines; he uses plot in a way dissimilar from best of Hollywood blockbusters, thrill-rides as it were. Takahata's Ghibli

films are episodic in nature, they tend to have a "this happened, then this happened, then this happened" structure arranged under a loosely conceived over-arching plot. Yesterday, Grave, Poko and especially Yamadas assemble a series of individual scenes and sequences that aren't concerned with pushing their meandering stories forward towards their final destination. As a result, there's a refreshing freedom to by found in Takahata's stories, even a baffling digression

like the Heike interlude in Poko not feeling entirely out of place because the pieces are placed so idly. This looseness extends further to the variety of stylization and the improvisational qualities of his animation - when each section functions in almost a vacuum, there's lots of room for Takahata to try on different stylistic hats and find a visual expression for the moment-to-moment personality of the film. In Poko, the depiction of the tanukis take on three basic styles, depending on the situational

appropriateness - they're introduced in a realistic, biologically accurate version of the animals; once we get to know them a little, they start to appear in an anthropomorphized version that finds them transformed into chubby cartoons who stand on their hind legs and wear little outfits; and finally they sporadically appear as flat, almost featureless caricatures I've read are based on a popular comic book take on the critters (but the hell knows if that's true, Mr. Wikipedia... if that is your real name.) The freedom to swing wildly from realism to comic book style is something that wouldn't work in a Miyazaki film where the stories rely on a cohesive whole - if Pazu in Castle

in the Sky changed in appearance from scene to scene the way the lead tanukis shift in style, it would undermine the world Miyazaki is building and knock you out of the story's flow. Takahata's episodic tales and stylistic experimentation work in codependency, it's difficult to imagine one working without the other. The variety of styles on display don't just extend to the tanuki, but Takahata's fondness for small interludes done in the style of ornate woodcuts, for example, or the mid-film parade

of yokai that faithfully reproduces traditional depictions of the folkloric creatures. There are sequences in the film illustrating the daily grind of a Tokyo commuter without imagistic hyperbole as well as cartoon-y brawls featuring Looney Tunes-esque violence between the chubby, bug-eyed elastic humanized versions of the magic raccoons. It all plays and you never think twice about it. I should also mention that Takahata's films share a certain grimness - obviously, a small child dying of malnutrition

in Grave is no joke, but even the sweet Only Yesterday features a young woman plagued by anxiety about things that happened when she was 10. Pom Poko's climactic piles of the dead raccoons (done in the realistic style) and the tanukis' ultimate defeat leave the film with dark undercurrents.

That dark undercurrent feels like the clearest expression of Takahata's personality and his soberness about the cruelty of life. It's easy to imagine just about any other filmmaker pulling their punches a little when it comes to the suburban sprawl's devastation of the local animal populations. This is, after all, theoretically a kid's film. Takahata just can't let the truth off the

hook, it's just not in his artistic nature. Unsurprisingly, the dominant environmentalist themes of the film feel like a residue from Miyazaki and his initial concept. The battle for survival and man's relationship to the natural world is also indeed a regular theme for Takahata, but the insistent environmentalist message ingrained in the rote "animals versus developers" plot can't really be strongly felt in his other work. Both that theme and the appearance of fantasy elements definitely belong

to Miyazaki, so, once again, it's easy to understand while Takahata doesn't hold this project close to his heart and how Miyazaki probably bears more than a bit of responsibility for the finished film. I would say, though, that the depiction of the tanukis themselves feels unique to Pom Poko in relationship to Ghibli's overall body of work. The tanukis as Takahata has realized them have a lustiness and vitality uncommon for the mythical creatures on parade in the rest of Ghibli's output. These guys look

to eat and fuck and dance and sing - their drooling discussion of the best part of mouse tempura is delightful; their exploration of human culture in the form of chowing down on MacDonald's is even more adorable. There's a Rabelaisian quality to their testicle-centric tricks, unfettered gluttony and insatiable sexual appetites. You can imagine them getting Pantagruel-esque revenge by spraying an enemy with the glands of a bitch in heat to watch their adversary get molested by horny dogs - and like in the story

of Gargantua and Pantagruel, there's an excessive violence floating around at the margins of the story. The tanukis' celebration of their initial small-scale victory results in the first of many raucous parties - the mood (of the audience) is suddenly undermined when the tanukis celebrate the death of three construction workers. They're literally killing their essentially innocent human adversaries and then laughing about it. Strangely, their lusty, undisciplined qualities give them a very human quality (as much

as the corpulent lead provocateur Gonta would hate to hear it.) Takahata's films are a contrast to Miyazaki in that way: Miyazaki works in more archetypal emotions, his characters and their feelings not realistic, per se, but of a more archetypal variety. Takahata's characters, even his magic raccoons, have a powerful specificity to their emotions - sure, Miyazaki's films are emotionally powerful as well, but they have a tendency to be sentimental or melodramatic, they are Hollywood-ish in their effectiveness.

The tanukis are petty and short-sighted, impatient and flighty, but they are also lovable along with these flaws. Takahata might be considered a cynic especially in comparison to Miyazaki, whose films almost exclusively end in triumph with the natural world flexing its muscles in a way that frequently borders on a deus ex machine. Pom Poko ends an a super down note that emphasizes the helplessness of nature to strike back. The emotions generated by Miyazaki's films are intoxicating, Takahata's films sobering.

Miyazaki deals in powerful emotions, Takahata in authentic. Not bad for a film about raccoon creatures with giant balls.

That dark undercurrent feels like the clearest expression of Takahata's personality and his soberness about the cruelty of life. It's easy to imagine just about any other filmmaker pulling their punches a little when it comes to the suburban sprawl's devastation of the local animal populations. This is, after all, theoretically a kid's film. Takahata just can't let the truth off the

hook, it's just not in his artistic nature. Unsurprisingly, the dominant environmentalist themes of the film feel like a residue from Miyazaki and his initial concept. The battle for survival and man's relationship to the natural world is also indeed a regular theme for Takahata, but the insistent environmentalist message ingrained in the rote "animals versus developers" plot can't really be strongly felt in his other work. Both that theme and the appearance of fantasy elements definitely belong

to Miyazaki, so, once again, it's easy to understand while Takahata doesn't hold this project close to his heart and how Miyazaki probably bears more than a bit of responsibility for the finished film. I would say, though, that the depiction of the tanukis themselves feels unique to Pom Poko in relationship to Ghibli's overall body of work. The tanukis as Takahata has realized them have a lustiness and vitality uncommon for the mythical creatures on parade in the rest of Ghibli's output. These guys look

to eat and fuck and dance and sing - their drooling discussion of the best part of mouse tempura is delightful; their exploration of human culture in the form of chowing down on MacDonald's is even more adorable. There's a Rabelaisian quality to their testicle-centric tricks, unfettered gluttony and insatiable sexual appetites. You can imagine them getting Pantagruel-esque revenge by spraying an enemy with the glands of a bitch in heat to watch their adversary get molested by horny dogs - and like in the story

of Gargantua and Pantagruel, there's an excessive violence floating around at the margins of the story. The tanukis' celebration of their initial small-scale victory results in the first of many raucous parties - the mood (of the audience) is suddenly undermined when the tanukis celebrate the death of three construction workers. They're literally killing their essentially innocent human adversaries and then laughing about it. Strangely, their lusty, undisciplined qualities give them a very human quality (as much

as the corpulent lead provocateur Gonta would hate to hear it.) Takahata's films are a contrast to Miyazaki in that way: Miyazaki works in more archetypal emotions, his characters and their feelings not realistic, per se, but of a more archetypal variety. Takahata's characters, even his magic raccoons, have a powerful specificity to their emotions - sure, Miyazaki's films are emotionally powerful as well, but they have a tendency to be sentimental or melodramatic, they are Hollywood-ish in their effectiveness.

The tanukis are petty and short-sighted, impatient and flighty, but they are also lovable along with these flaws. Takahata might be considered a cynic especially in comparison to Miyazaki, whose films almost exclusively end in triumph with the natural world flexing its muscles in a way that frequently borders on a deus ex machine. Pom Poko ends an a super down note that emphasizes the helplessness of nature to strike back. The emotions generated by Miyazaki's films are intoxicating, Takahata's films sobering.

Miyazaki deals in powerful emotions, Takahata in authentic. Not bad for a film about raccoon creatures with giant balls.

(I feel like I should mention that at one point in the film, a background character is wearing a varsity-style jacket that simply reads "Cosby." I have no idea what the filmmakers are getting after with that. The English that appears in the film mainly serves to parody the commercialism and lack of respect for nature in America, so I'm not sure how Cosby features into that. I have a bad feeling it might just be a little of Japan's famous racism peeking through.)

OCEAN WAVES

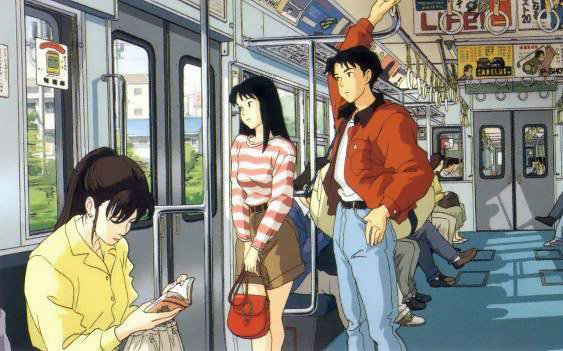

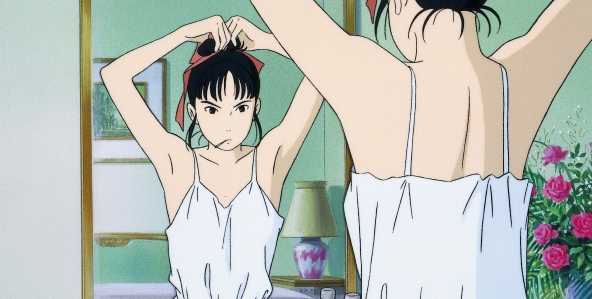

I'll readily admit I came into this film confused - because of its similar subject matter and equally vague title, I mistook this film for Only Yesterday, another Ghibli film rarely screened in the United States (of America.) I spent a large part of the screening trying to figure out how Isao Takahata could have made such a mediocre film, where his sharp perspective and adventurous sense of creativity had gone. When the end credits finally rolled, it confirmed what I had begun to suspect was true: Ocean Waves is not a Takahata film at all, but a made for t.v. movie from a Ghibli second-stringer of whom I hadn't heard, 34 year-old Tomomi Mochizuki. Actually, the final scene in the film confirmed this definitely wasn't a Takahata film before the credits rolled shortly thereafter - the ridiculous, unearned happy ending is something that simply wouldn't have appeared in a Takahata film, even at gunpoint. (Yes, I truly believe he would have chosen death rather than end his movie on such an emotionally false note.) Paired with the aggressively minor film that preceded the phony ending, I knew this wasn't his work. Clocking in at 72 minutes and having precisely the level of ambition and complexity implied by the label "t.v. movie," the plot has 5 basic parts that eschew any of the narrative tension that could be mined from their set-ups. 1) A big city girl from Tokyo named Yoko movies to a small-town and catches the attentions of two boys in her class, a cool guy with poor grades and the class president/big-time nerd. He wears glasses. 2) On a class trip to Hawaii, the girl borrows a lot of money from our cool hero under false pretenses. 3) The girl uses the money to buy plane tickets to visit her semi-estranged father in Tokyo. Through a series of convolutions too mundane to be recounted here in detail, our hero Nobuo ends up going on the trip to the big city with Yoko. 4) When they return to the small-town, they suffer from tittering gossip about their night in a hotel together and the girl ignores the boy. 5) Jump to: they've graduated high school, Nobuo and class president go to a (1 year?) reunion and then the boy reconnects with the girl at a train station at Tokyo. There's not really any driving story, the big set-piece being the night in the hotel in Tokyo, where the girl returns after a fight with her father only to get drunk on rum and cokes and pass out, so the boy has to go sleep in the bathtub. That's the big exciting part of the film. The rest of the movie is the students hanging around at school and getting into very insignificant arguments about the haughty big-city interloper. The class president and boy hero have some very minor conflicts over the girl in addition to a lot of "do you like her?" "well that depends - do you like her" type conversations. The film has the pacing of a tire deflating. The animation is very standard; the only real stylistics on display are scenes with a white border that changes in size and a few shots that emphasize depth of focus in an uncommon way. It's all very simple and since it chooses "the myopia of youth" as a major theme, the story has a tendency to over-emphasize the mundanity of the proceedings. That might, however, be giving too much credit to the design and intention of director Mochizuki.

As I mentioned in my introduction, last year at I wrote about From Up on Poppy Hill after seeing it at the Toronto International Film Festival and films like Ocean Waves makes me think I maybe didn't give it enough credit. Whatever its flaws, Poppy Hill is a lively film, even if it concerns as a hoary trope in its "let's save the beloved rec center!" as played out as Ocean Waves' middling teen romance. As much as Ghibli is associated with being spirited away to whimsical realms, they also have a side business in these little nostalgic melodramas. My confusion as to the creator of Waves stems from the fact that Ghibli did make more than a few of the same kind of wistful looks back at youth - even some of Miyazaki's overtly fantastical works like My Neighbor Totoro tap the same kind of nostalgia. These films have a tendency to be farmed out to lesser Ghibli talents like the obscure style="margin:8mm;">Mochizuki, but, but also Miyazaki's own son Goro - another filmmaker of dubious talent. Even Grave of the Fireflies' fidelity to reality offers an extreme version of the "looking back at youth" style. In fact, Takahata specialized in these more personalized films; as I mentioned, I confused Ocean Waves for Only Yesterday because of the similarities in content. Three of the four Takahata films made for Ghibli fit this mold with varying levels of straight-forwardness. Just by their nature, these Ghibli nostalgia pieces seem minor in comparison to the rest of Ghibli's output - the only one I can think of that's commonly in the same high regard is the universally praised Grave of the Fireflies. But that film is a knock-out on a number of levels - stuff like Waves and Poppy Hill seem content to mine a gentle vein of school-kid days worrying about grades, fomenting minute rebellions against harried authority figures and falling in (puppy) love. Their over-riding connection is exploring the notion of "what was and what could have been." They don't have any intention of knocking your socks off (which Mythbusters proved is impossible, anyways), so they meander along on a wave of slightness, ebbing gently over the rocks in their story's paths. The hero of Ocean Waves must face down nothing beyond gossip and a teenage girl's flightiness - even when 20,000 yen are on the line, there's no sense of urgency. He seems to forget about the money for several months and then just as easily gets repaid by the girl's wealthy father. The tension between the laid-back youngster and his four-eyed class president buddy similarly diffuses before percolating to any sort of a boil: they both like the girl but don't seem too wrapped up in their emotions; they both regard each other warily, but without any real malice or jealousy. The film does feature the requisite amount of perviness in the form of a teenager tennis player's hefty jiggling boobs, but in the story of teenage boys in love, this minor digression into top heavy women doesn't seem as forced and indefensible as it does in most anime. The following shot of the Tokyo hipster Yoko's shirt flying up along with her leaping strike comes closer to crossing the line. But all-in-all this film's main characteristic is its inoffensiveness - even the animated leering at the ample-bosomed tennis competitor garners an unenthusiastic reaction from the boys watching her. They're bored with their own puerility and in need of a healthy shaking-up.

Ocean Waves have a huge virtue in its portrayal of the city girl forced to live amongst country bumpkins. Yoko stands apart from her peers, especially in her own mind. When she cons money off of Nobuo, she doesn't exhibit any particular craftiness, nor does she lean heavily on her feminine appeals. She simply assumes the rubes will take her at her word and she's right: no sooner has Nobuo accepted her at her word and generously bailed her out that she wanders off with the substantial wad of dough. As a self-possessed teenager, but especially as a teenager trapped in a new inferior life, Yoko vacillates between haughtiness and attempting to fit in. Her abortive visit to Tokyo to re-connect with her re-married father (and spend the night in her old bedroom) constitutes the most intense part of the film as this sequence is the only moment when real emotions seems to be at stake and the conflict doesn't resolve itself with no effect on the flow of the narrative's babbling brook. She's the single character in the film for whom life doesn't amble along more or less according to plan. Her sin is a pretense to her old life, getting doubly shown up in front of the skeptical Nobuo first in the well-meaning rejection by her father and then while showing off her old boyfriend. Nobuo's reaction to the lunch in the cafe with Yoko and her pretty, urbane ex-beau can be read a variety of ways; the boyfriend apologizes for making him jealous, while Nobuo tells the beau and Yoko are both obnoxious bores. A little bit of both statements is probably true. But Yoko takes a weird pleasure in Nobuo's impatient reaction - she suddenly begins to act more mature and reasonable, even if just as aloof. She seems to have confirmed the alienness of her life in Tokyo to a rube like Nobuo and no longer seems as compelled to act out for the brief remainder of the Tokyo trip. Whatever to actual source and meaning of Nobuo's angry impatience, it serves to affirm her self-image, that Nobuo cannot understand her. When they return to school, she ignores him and hangs out with her only friend in the school. Eventually, gossip pushes both of them too far, being linked to Nobuo a slap in the face to her self-perceived separateness from the small town. Their shared anger leads to some literal slaps in the face, but then ebbs and nothing really somas to come of it. Yoko as a character is refreshingly realistic as far as the usual portrayals of teenager girls in the movies. She's smart, but quick to temper, capable of real maturity and thoughtfulness in spite of her perpetual outrage and condescension. Her period causes terrible cramps. Her fierceness and inability to reconcile her self-image with her new life, however, bring us to the silly climax of the film. Yoko has spent the entire film bitching about the town and belittling our hero - a scene at a floodlight temple following the reunion dinner I suppose is intended to be sentimental, Nobuo thinks back to his time with Yoko and voice-over of her dialog from the film plays at length, as though Nobuo is reveling lovely memories. But the voice-over dialog bubbles with suppressed rage, every word laden with caustic intent. There's nothing sweet about it. The sudden shift to sentimentality is disorienting and utterly undermined by her voice itself - the meaning of the respite at the beautiful temple simply doesn't match up with how the film makes the audience feel. The capper comes in the final moment of the movie, when our hero rushes to catch Yoko before she boards a train. This is a young woman who has been deceptive, hypocritical, mean-spirited and condescending the entirety of the film. Surprisingly, she has seen Nobuo and decided to not get on the train - they lock eyes and in voice-over our hero announces "That's when I knew I had always been crazy about her." As the scene was unfolding, the film's musing on childhood being a small world and going to college offering perspective made me think he would suddenly realize how ruthlessly selfish she had been and how little they had in common other than being trapped in the same small world. Instead, cue whirling 360 degree camera movement and a sweeping romantic score. I didn't even need the credits to know Takahata wasn't at the helm.

christopher funderburg

8/23/12

UNRELATED ARTICLES

<<Previous Page 1 2 Next Page>>

home about contact us featured writings years in review film productions

All rights reserved The Pink Smoke © 2012