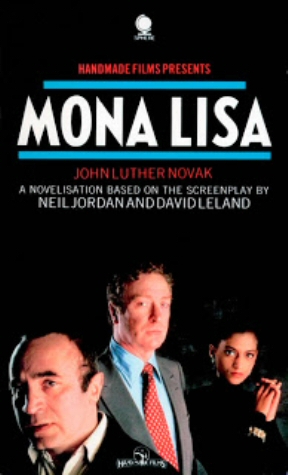

NOVELIZATION APPRECIATION

MONA LISA

by John Luther Novak (based on a screenplay by Neil Jordan & David Leland)

john cribbs

"George's mood was deteriorating fast, a counterpoint to the overall atmosphere of harmless gaiety being radiated by everyone he could see. The simple pleasures of a seaside walk on a sunny day were too straightforward to deal with the complex rage that was in him. George scowled at the ground." - Mona Lisa (novelisation)

"I like the seaside! I've always liked the seaside! Do you like the seaside?" - Mona Lisa (movie)

Neil Jordan likes the seaside. But his characters are never there for the traditional reasons - you won't catch any of them sunbathing or plunging headlong into the tall waves of the cool salt water. More likely you'll find Stephen Rea's disheveled Danny hunched over in the sand in Angel, drowsily training a gun on the man he's about to kill as they sit across each other like two awkward kids who met during a holiday neither was excited to go on in the first place. Danny asks his target questions he's not honestly expecting answers to, desperate to know why an innocent young woman - the witness to a mob execution - would be callously struck down by the gunmen, the motive behind such senseless violence as immeasurable, yet equally inevasible, as the boundless body of water before them: it can neither be ignored or ever fully understood. For Jordan's characters, especially the male leads from his films of the 80's and 90's, an essential lack of understanding is the key frustration that motivates their actions and incites their ultimate breakdown, the limit of their own understanding marked by the perimeter where the land ends and the sea begins. These men never travel beyond the wharves, quays, piers, berths and jetties of Jordan's ironic coastal settings - they stand alone regarding the inhospitable brine before them with surly expressions, hilariously out of place with their pale faces in dark clothes, the idea of any kind of leisurely composure typically associated with the warm sunshine of the waterfront bewildering to them. They know that they'll never set out beyond this marginal barrier between land and ocean, any more than their apprehension will ever overreach its finite capacity - the seaside may be beautiful, but it will forever remain as beguiling and frustrating as an enigmatic Mona Lisa smile.

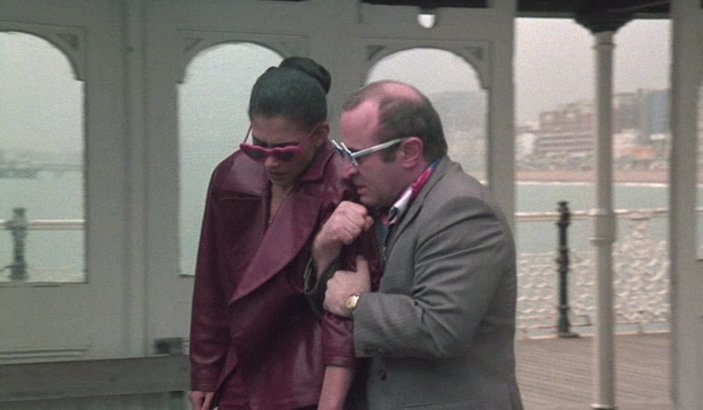

Hence Bob Hoskins' George confronting Cathy Tyson's Simone on the Brighton pier, arguably beat-for-beat and word-for-word the most pitch-perfect scene of Jordan's career, his best directed and best acted, and by far the most emblematic of what his characters are after coming into conflict with where they end up. George is a discarded hood who's returned from a noble stint in prison to find himself estranged from his wife and daughter, stuck with the seemingly menial task of chauffeuring a high class prostitute around London in his '62 Jag. Having fallen for the smart and seductive Simone, he agrees to sever ties with his criminal associates by helping her rescue one of her fellow street walkers from their grasp. Having spirited the girl away to Brighton's Royal Albion Hotel, the site of Simone's own liberation years earlier, George is appalled to find the relationship between the two young women may be more intimate than he has realized. Feeling used and dejected, every recent event of his life that's flustered him culminates in a tirade against the woman he's risked everything for, revealed in his eyes to be a manipulative, man-hating lesbian. For George this is the ultimate betrayal, having convinced himself there was more to Simone than her sordid nocturnal activities, that she was a helpless victim of the rampant exploitation he's witnessed rather than a participant in the kind of kinky alternative lifestyle to which he's so oblivious he's not even sure how to come to terms with it:

Simone: "You don't understand, do you?"

George: "No, I don't understand. What don't I understand?"

Having spent the entire movie searching for what it is he's supposed to understand in the seedy enclosures of peep shows and knocking shops, George has journeyed to sunny Brighton - the geographic equivalent of his perception at its fullest - only to find the unobscured truth to be disappointing. Just like Butcher Boy's Francie Brady, maniacally indulging in the run-down attractions at the boardwalk carnival outside the Over the Waves Hotel in Bundoran, a seaside getaway he's idealized growing up from stories of his parents sharing an ideal honeymoon there, an illusion that's duly shattered by a hotel owner who remembers Francie's alcoholic father's abuse towards his mentally unbalanced mother. This turns out to be the missing piece of information required to send Francie on his gleefully morbid mission, as he narrates upon leaving Bundoran, "Yes indeed, it was the end of the line," acknowledging both the furthest he can travel geographically and the last bit of revealing information his young brain can process before boiling over.

Vacation spots like Brighton and Bundoran are specific to the director's preoccupation with the seaside, his characters' revelations directly connected to the garish reality of these picturesque littorals. Such a location serves as the framing device of Jordan's novel The Past, published just before making his directorial debut, in which the narrator uses two postcards depicting the esplanade of a Cornish seaside town his grandparents once visited to form a mental picture of the surrounding boardwalk, canvas awnings, deckchairs, railings and bathing houses, slowly expanding beyond it to visualize the entire resort: "Canvas! Yards and yards of it are implied, painted in those circus stripes, those warm blues, fawns and yellows, stretched over windbreakers, tautened umbrellas and Punch and Judy stands and even barrel-organs. Was it the age of canvas?" The narrator replicates the seaside as a means to access memories of his grandparents by proxy, a narrative process that leads to the revelation that their "vacation" was a cover to conceal the birth of an illegitimate child - the narrator's mother. In The Miracle, which is a kind of reworking of The Past (the estranged mothers even share the same name, Renee, and are both actresses) set in Bray,*the coastal setting is so ideal that its fantastic elements overshadow the very real issues of alcoholism and abandonment that threaten to ruin a family rather than bring them back together.

George also has ideals when it comes to traditional, heterosexual love and family, which he spews forth on the Brighton pier: "They walk arm-in-arm, 'cuz they love each other. And they get married, so they can love each other more, and have a lit'l ba-bee!" His unrequited expectation that escape to the beach will mean happiness for himself and Simone turns out to be as illusory as Una and Michael's romantic elopement in The Past, Sam and Renee's perfect marriage in The Miracle, Da & Ma Brady's fairy tale honeymoon in The Butcher Boy. Truths under the bright sun above a breezy beach setting are rarely so readily accepted as Kitten revealing her sexuality to a smitten Bertie Vaughan in Breakfast on Pluto (which, due to the casting of Stephen Rea as Bertie, plays almost like a "correction" of the famous reveal from The Crying Game); often the facade crumbles bitterly, like Jimmy riling himself into a state of confusion ending in violent reaction coming to terms with the fact that mysterious obsession Renee Baker is in fact the mother who abandoned him.

False surfaces and revelations abound in Christopher Priest's A Dream of Wessex (1977),** in which a seaside resort is also the subject of memory: or rather, the entire getaway (a fictional island called Wessex between "Blandford Passage" and "Somerset Sea") is one big virtual simulation in which the collective unconscious of hypnotized individuals with no memory of who they really are interact under the watchful eye of a giant corporation as an experiment in future imagining. It may be this similar preoccupation with the beach that scored Priest writing duties for the Mona Lisa novelisation - the beach-based constructed-reality motif continued in his 1981 novel The Affirmation, which centered around an archipelago of exotic islands, and The Glamour, which like The Past also involves a mysterious postcard sent from a beach resort (in that case, Saint-Tropez) that the main character uses to access his lost memory. But I think it was even more to do with Dream of Wessex's depiction of a woman who finds herself trapped and tormented by a chauvinistic jerk. Julia, Wessex's hassled heroine, isn't a streetwise survivor like Simone but similarly finds herself stalked by a creep she used to sleep with, forced to turn to an unlikely male protector she initially sees as fat and ungroomed (granted, he's been in a hypnotism-induced coma for many months) since her stalker has programmed everyone in her utopic Wessex to turn against her. Priest is from England, just like Judas Priest, and was himself "unleashed in the east" as part of the new wave of British science fiction writers that included J. G. Ballard, Brian Aldiss and Michael Moorcock, all of whom gained popularity in the 70's. Best known in the film community for his musician's feud novel The Prestige, which formed the basis of the 2006 film directed by Christopher Nolan (for what it's worth, and it's not much, Nolan's best movie), Priest is recognized in literary circles for such early Wellian efforts as Fugue for a Darkening Island and the Hugo-nominated Inverted World.*** So the crime genre isn't his specialty, which may explain why "John Luther Novak" is credited as the author of the Mona Lisa novelisation. Priest's other movie tie-in effort from the 1980's - the novelization of Short Circuit**** - could be at least nominally considered sci-fi, although even that got published under the nom de plume Colin Wedgelock.*****

Reading the novelization - sorry, novelisation - I wondered whether or not Priest had familiarized himself with Jordan's novels before tackling the assignment. Priest's approach is to use lots of dialogue and sparse description except in the longer scenes of George alone, checking out the strip clubs or tailing Anderson around town. Not an uncommon practice for the pragmatic nature of these expeditiously churned-out tie-ins but the complete opposite of most of Jordan's fiction, lyrical and prose-heavy and often grounded in subjective narration. Priest still manages to capture the essence of Jordan's sensitive, observational narratives, especially when it comes to excavating the grace beneath George's rough exterior, and recalls the utilitarian method of Jordan's stripped-down screenplays.

So if Priest was so successful at channeling that Jordan feeling, how come Jordan, an established writer of books and short stories, deferred novelisation duties to Priest rather than just banging it out himself? It may have something to do with the fact that the Mona Lisa script originated from David Leland, who as the writer of Alan Clarke's Made in Britain was no stranger to crime dramas centered around a tiny angry Englishman. Leland made his directorial debut the year after Mona Lisa with Wish You Were Here, also set on the Sussex shore, which starred Emily Lloyd (her first film, rosy-cheeked and still years away from being roundly rejected by every director in Hollywood) and Tom Bell (star of the excellent 1978 mini-series Out, which like Mona Lisa is about a man released from prison - "the stink of the knick" on him - to a wife and teenage child who aren't exactly happy to see him again, although Bell's Frank Ross is a little more steely and resourceful than Hoskin's George; Brian Cox played the sleazy Michael Caine crime boss-antagonist in that). Wish You Were Here is the flip side of Mona Lisa: Lloyd's Lynda Mansell is actually ahead of the times, a liberated and precocious young nonconformist and self-conscious affront to 1950's sensitivities, the exact opposite of awkward, easily-rattled George. Lynda makes all the men around her feel like George, handsome young suitors and stuffy old conservatives alike, mocking their attempts to dominate her or to suppress her free-spiritedness, befuddling their efforts to turn her into what they expect her to be. Jordan must have been inspired by Lynda's creative, confident, beachbound cutie to create The Miracle's Rose, but what's really interesting is how Lynda is so completely the opposite of George - it would be amusing to see those two characters together in a criminal father-unruly daughter comedy (actually...I guess that would just be Cookie).

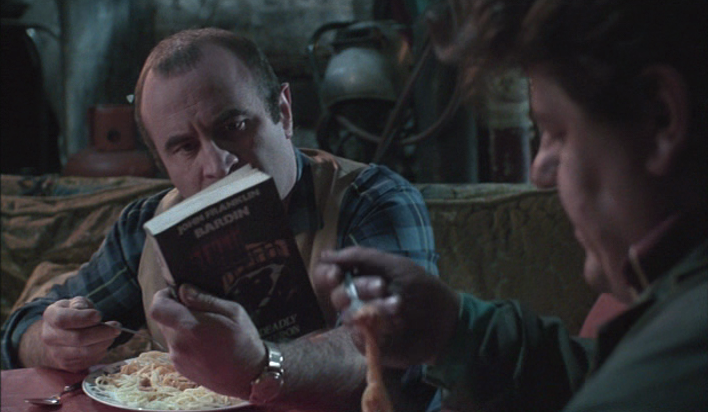

Mona Lisa is the only of Neil Jordan's films to be novelized; I should know, since in 1992 my parents still sorta paid attention to the kinds of movies I watched****** and I was forced to seek out a printed version of The Crying Game to find out what the big secret was. My search came up empty, and I left the bookstore with a swiftly-confiscated novelization of Basic Instinct instead (if I couldn't discover the secret of The Crying Game, I was going to at least make an effort to find out what happens in the already-infamous interrogation room scene of Verhoeven's movie - funny enough, both answers turned out to involve genitalia.) But no Jordan cash-ins, which is kind of surprising considering how literary the director's work is: besides being a published novelist and apt adaptator/integrator of fiction by folks like Angela Carter and Frank O'Connor, narrative and story construction is actively represented in Jordan's films. Just think of Rose literally narrating the lives of the people in her small beach town, referring to them as her "characters," in The Miracle, or Kitten's obsessive chronicling of her search for the "Phantom Lady" in Breakfast on Pluto. In addition to abstract narratives like Figures on a Nun-Swept Pier and Footprints in the Custard, actual books pop up in Jordan's films too - specifically, noir/mysteries such as Cornell Woolrich's The Night Has a Thousand Eyes, Beverly D'Angelo's beach read of choice in The Miracle. In Mona Lisa, Thomas has George read The Deadly Percheron by John Franklin Bardin, a genuinely weird thriller about a man tormented by leprechauns, who taunt him and demand he perform bizarre tasks like wearing a hibiscus in his hair, giving away quarters on the street and whistling in public places (seriously, that's what it's about; Jordan pays visual homage to the book by having the Mini-Tones, Jack Purvis and Kenny Baker of Star Wars/Time Bandits fame, as dancing dwarfs on the Brighton pier). And it's to Thomas - the mystery fiction buff - that George, like Rose and Kitten, presents his own life as a serial of sexy intrigue, relegating himself to third person: "He comes out of the knick, and they give him a job driving a tall, thin, black tart." Like Rose and Kitten, he's just given a pulpy, awkwardly poetic title to his own story. The final lines of the movie sound like an excerpt from the last chapter of this book:

"She was trapped. From the first time he met her, she was trapped. Like a bird in a cage. But he couldn't see it. Well, he liked her too much. And he was the sort who couldn't see what was in front of his face. And there she was, in pain. When you're soppy about someone, well, you can't see things like that, can you? And there he was, the soppy sort. Oh, she had faith in him. She believed in him, and he had a lot of hopes for her. But, there was love. Yeah, she was in love all right. She really was. But not with him...And that's the whole story."

None of that turns up in Priest's version - the final chapter is slightly different from the end of the movie, which confirms that the book (like most novelizations) must have been based on the script rather than the finished film. Without the benefit of seeing the movie he was adapting to the page, Priest's most obvious handicap in writing a Mona Lisa novelisation is that Bob Hoskins couldn't star in the book. Few films are so centralized on one amazing performance as Hoskins playing George; take away Hoskins, who Pauline Kael likened to "a testicle on legs," and you're left with half a character, so that no matter how well Priest describes him as a short, crass, seething ball of frustration - and Priest wisely doesn't even bother trying - he has about as good a chance of getting inside George as a patron of the Louvre has to touching the real Mona Lisa. Sure, he can take a shot at translating the image of Hoskins wearing "a rakish leather bomber jacket and tight-fitting trousers, rounding off the effect with a flowering shirt and a pair of high-gloss Italian shoes," but no description would do justice to the visual. As far as drawing the character from scratch Priest is a competent sketch artist, but Hoskins is Da Vinci - whereas very few actors can lay claim to a signature role, Hoskins has two, this and The Long Good Friday, with several solid supporting roles to boot, and George was the part he was born to play******* (only to lose the Oscar to Paul Newman's successful sympathy vote campaign for The Color of Money - tragic that).********

* Jordan returned to the same location to shoot his latest film, Byzantium.

** Weirdly, Dream of Wessex was re-titled The Perfect Lover by its American publisher: the cover art for the American edition depicts a surfer gliding on a wave and the description on the back betrays none of the book's science fiction plot, so it seems like a straight-up novel about some dude likes to surf.

*** It lost to Ursula K. Le Guin's The Dispossessed, but so did Philip K. Dick's Flow My Tears the Policeman Said and Niven/Pournelle's The Mote in God's Eye, so it's nothing to kick himself over.

**** Short Circuit's Steve Guttenberg would go on to star in Neil Jordan's Hollywood miscalculation High Spirits. Incidentally, in his recent autobiography The Guttenberg Bible, Steve-o doesn't mention High Spirits once. It's odd, because he goes off-topic at one point to mention how Peter O'Toole is one of his favorite actors - why not tie that into a lean three sentences about what it was like working with O'Toole and then-popular actress Darryl Hannah on Neil Jordan's flip flop of a U.S. debut? It would have been effortless. Christ dude, if you're already taking time out to acknowledge your participation in "future hot-director, contemporary movie star actress" failure The Bedroom Window and note the existence of Don't Tell Her It's Me a.k.a. The Boyfriend School, you'd think Neil Jordan was worth one lousy paragraph, or even a footnote. This footnote about High Spirits is 100 words more than Guttenberg had to say about it!

***** To complicate all this pseudonym nonsense, Priest should not be confused with the comic book writer Christopher Priest, who up until the early 90's was known as Jim Owsley. Owsley/Priest used to edit the Spiderman books and wrote a mini-series in which The Falcon fights a Sentinel, and wins! (No shit!) Post-name change, he's noted for more serious/experimental work like his extended run on Black Panther. He's never given a reason for changing his name, although it apparently has something to do with him being an ordained Baptist minister. Just gonna throw this out there: the British Christopher Priest should change his name to Jim Owsley.

****** I'll always remember my dad popping The Godfather into the VCR, then turning to my 13-year-old self before starting it and stating very intensely, "We'll watch this, but you can NOT feel sorry for the people in this movie. They are criminals, and they deserve what they get." During Jimmy Caan's harsh execution, I found myself thinking 'Jesus christ, dad!'

******* Can you believe the original duo to play George and Mortwell were Sean Connery and Anthony Hopkins? Also, executive producer Denis O'Brien suggested Grace Jones for the role of Simone. The hell kind of movie would that have been??

******** I was very sad to hear about Mr. Hoskins' recent illness and retirement from acting. He really deserved that Oscar for Mona Lisa, and at least a nomination for Unleashed. He's scummier than Caine in that one - maybe if the producers had kept the original title Danny the Dog, his performance would have been more globally recognized.

<<Previous Page 1 2 Next Page>>

home about contact us featured writings years in review film productions

All rights reserved The Pink Smoke © 2013