MONA LISA: THE NOVELISATION

page 2

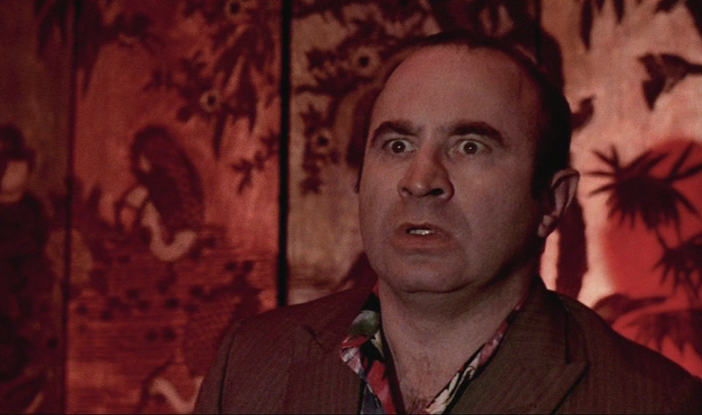

One notable difference between Hoskin's George and Priest's George is the diction: I don't know if the good people at Sphere Books Ltd. insisted on grammatical correctness or what, but the essence of Hoskins' personality is somewhat lost when "He don't" becomes "He doesn't" and "innit" is replaced by "isn't it;" somehow "You're no night nurse" just doesn't conjure the image of Hoskins quite as clearly as "You ain't no night nurse!" Hoskin's natural Cockney spew is so much a part of George's uncouth carriage and quickfire indignation; losing that East End attitude doesn't do much to help the dialogue transcend the normal court stenographer feel of novelizations. Priest even uses "pimping" rather than "poncing" in the scene where George and Simone are arguing about his job title. Sphere Books is out of London,* so I doubt any of these changes were based on some attempt to "Americanize" the text, and Priest does incorporate Brit terminology like "recharged his drink;" Thomas, instructing George on how to aim his gun, recommends he "Go for the goolies;" there's the description of Simone being dressed in a "simple white shift" and liberal use of the word "punter," a word never uttered by anyone in the movie (and I'm not 100% sure I get what it refers to - supposedly it's a customer, or john, but in the book the context seems to be someone who's ignorant of the workings of the criminal underworld, like a mark or a rube.) George still asks for a "cuppa tea" at the brothel in the book, so I could be making more out of the "cleaning up" of the language than it actually matters. Still, the dialogue divergence makes it unclear whether Priest had Hoskins in mind while he was inking out his novelisation - although I can definitely see Robbie Coltrane instructing him to go for the goolies - but he either way, he clearly understands the character of George. After relating his feelings on returning to the real world following his prison stint ("The sandwiches were still the same"), Priest nails other people's reaction to his existence with this moment entering a cafe and approaching a waitress: "She saw George, and immediately lost interest in him." As for George's response to other people, particularly those above his class, Priest taps into George's sense of humor in the way he relates to a hotel commissionaire: "For old time's sake, George sneaked in another pointed look at the man's shoes." Priest knows that George is considered riff raff among the rich and is hardly considered at all by his fellow working class, although sadly one of the best lines from the movie pegging him as an oblivious outcast doesn't appear anywhere in the book:

Thomas: "You'll never look like other people, George."

George: "Fuck. Is that true?"

Because everything in the novel is internalized from George's point of view, it would be hard not to write the character as self conscious as Priest does. It would be easy to simply portray him as hopelessly ignorant and out of touch, but Priest understands George is more complicated than that. Robbed, however, of the intricate mannerisms and line readings Hoskins provides that show George is at least a little ahead of the game - even if it comes from the same kind of inherent prejudice and mistrust that constitute his ignorance - Priest is forced to make minor changes so that these subtle character insights are more clear. Like this interesting little discrepancy between book and film: in the night scene at King's Cross when the pimp recognizes Simone in the backseat of the Jag, Priest describes George as having "unusual foresight," since he's locked the car before driving onto the bridge and therefore isn't too concerned when the pimp tries to get into the car. Whereas, in the movie, George hasn't locked the door and the young prostitute lets herself right in, which is how she sees Simone and why they can't just up and drive away when the pimp gets aggressive. This subtle change is an opportunity for Priest to show that he is hinking about George's absent-minded nature, even while acknowledging a certain street savviness; without Hoskins' flustered reaction to all this activity inside his vehicle, there's really no reason not to have the scene play out slightly different and give him a little more credit in the department of common sense. (Whether writing about a similarly na´ve, short, lovable hero with a rough exterior in his Short Circuit novelisation helped Priest gain perspective to George as a character is anyone's guess.)

Priest also does a good job maintaining George's general ignorance: rather than making him seem a complete tosser, he establishes that George has ideals about sex and relationships and an old-fashioned honor-among-thieves mentality that originate from the same set of standards. To George, Simone rejecting him for Cathy is the same as Mortwell neglecting to look after him once he's out of the knick - she's failed to live up to a set of standards that she couldn't possibly know existed, since they're based solely on George's expectations; like many one-sided romances, she doesn't appreciate just how much George has made her the geometric center of his world. It makes me think of my favorite Priest novel, the topographical adventure Inverted World, in which an entire city is moved across a (post-apocalyptic) world on giant tracks; the people of the city believe that if they fall too far behind a perpetually moving "optimum," they will slip into a surreal kind of oblivion (too complicated to go into here, but the optimum essentially represents the vertice of a rectangular hyperbola, with distortions becoming more severe the further one travels from it.) Helward, the "hero" of the book, is, like George, ignorant of the world around him. Becoming part of a scouting guild, he reluctantly follows his superior's instructions and accepts a mission into the "behind" which takes him away from the city for several years, not unlike George's incarceration - when he returns, he too finds himself involuntarily estranged from a wife and child. The secret, repressive society he's part of are even kind of pimps a'la Mortwell & co.: since there's a higher amount of men than women in the city, in order to procreate they have an exchange program with primitive villages they come across where they take local women into the city to get knocked up and make babies, after which the mothers are more or less discarded. Priest switches back and forth between first and third person narratives so the reader learns about the world through Helward's perception (the fact that the city moves at all is kept from most of the population), but is then able to see just how blind Helward is to the way things really are. Because for all Helward's experience (ages of the city's people are measured in miles rather than years), he really doesn't understand what he's supposed to understand. In the big ending, the big reveal, the barrier of his ignorance turns out to be - naturally - the ocean. The city has a guild whose job it is to build bridges across terrain obstacles like rivers and gorges, but in the 500 or so years of the city being pulled forward they've never hit the sea; they're not even aware of the existence of oceans (that's right, it was Earth all along!) Despite a compassionate woman (the Simone surrogate if you will) who tries to bring him to some sense of reality, in the last chapter Helward literally tries to swim the length of the Atlantic Ocean. The beach isn't just a symbolic obstruction of understanding, he literally doesn't know what an ocean is. So many recent science fiction films have correlated the ocean with the limit of human experience/knowledge/understanding (like The Truman Show, which ends with Truman sailing the ocean to the literal end of his world) or overbearing challenge of his biological destiny (like Gattaca, with Ethan Hawke transcending his limited physicality by besting genetically superior Jude Law in a swimming race in open sea - hm, Andrew Niccol likes his metaphorical ocean almost as much as Neil Jordan!) Alex Proyas' Dark City especially comes to mind, its final image of Rufus Sewell walking out on the pier of the mentally-constructed Shell Beach, the "impossible" location having been a literal dead-end prior to his confrontation and defeat of the creatures who held him in a false reality. Dark City was co-written by Lem Dobbs, whose The Limey also sees its gruff British gangster coming to terms with what he didn't understand, the subject once again being a girl, on the unforgiving coast of an unfamiliar ocean (hopefully that's not too shabby a transition to get back on the topic of Mona Lisa, which is what this article is supposed to be about).

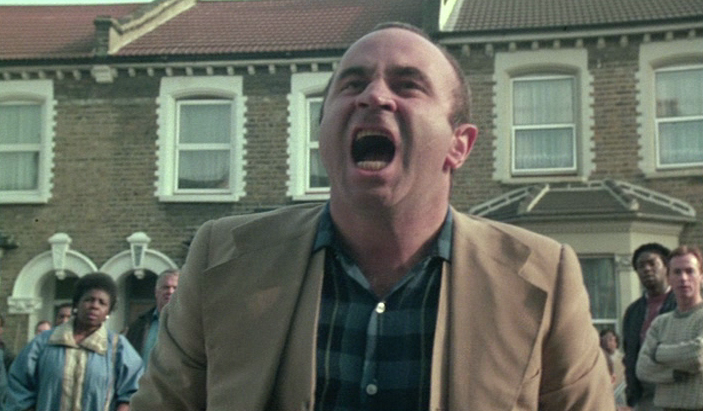

It's not really Simone's fault that she leads George to the brink of eruption on the briny edge of Brighton - she knows how to survive and who she needs to manipulate to get what she wants, but she never presented herself as anything different. As she points out, she's available to any man who can pay her fee, but to George that just means she's willing to give herself to anyone but him ("What's wrong with me? What's the matter, am I too old for you?! Am I too cheap?! Eh?!!") What he doesn't get is that, if anything, she finds herself even more disappointed by the way things turn out for her. Having once embraced freedom by the same shore, safely hidden in a hotel straddling the Brighton boardwalk, she finds that her return invites nothing but terror and violence: just like Jordan's male leads, she's idealized the seaside from an off-screen trip taken long ago only to learn that the past is the past - the present is just disappointment and ruin. Jordan often ties the ocean to the past of a woman: Simone, Renee Baker, Francie's mother. In the short story "Mr. Solomon Wept" the beach brings memories of a dead wife; "Seduction" opens with one boy creating the narrative for his friend of a girl running on the beach; in "A Love," set at Great Northern Hotel in Donegal, Jordan describes the sea as "breathing like a woman" - the sea is as alluring and unfathomable as a female. At least in Simone's case, so you can hardly blame George for being soppy about her, liking her the way they sing in songs, even though a successful union between them was always as unlikely as that of man and a dead girl, a straight man and a transgender or a young man and an older woman who turns out to be his mother. Sam's obsession with Renee Baker, or Francie's with the Virgin Mary, or the unnamed narrator of The Past with his mother Rene are all cases of women subjected to a male's idealized projection of a person they're not, or being cast in the role of something that's bigger than they are - even the political agenda of Michael Collins is mawkishly paralleled the story of two friends fighting for the love of Julia Roberts. Where the real Simone ends and begins is a complete mystery to George, so that when he's made the decision that she's his own fairy tale princess - and since she reinvented herself at Brighton, it's like Simone really is this mythical beauty who came from the sea, like Ondine - his disillusionment has nothing to do with who she actually is. Like their picturesque surroundings, Simone has failed to meet his simplistic ideal of purity and revealed herself to be as much a front as the garish constructs of the Brighton pier. You can't hate Mrs. Nugent for wanting to protect her son, or Renee for trying to make up for leaving hers, but Francie and Sam can project their frustrations over shattered fantasies onto these distorted reflections of their own choppy ocean, and the more George links Simone her past, geographically equated to Brighton, the less like the enigmatic Da Vinci painting she appears and more like just a cold and lonely, lovely work of art.

To compensate for the loss of Cathy Tyson's soft, patient, almost regal manner of speaking, Priest treats Simone as even more of a mystery, as much to the reader as to George. In the scene of their initial meeting in the movie, Simone sees George first and sizes him up from high on the landing of the hotel like the untouchable angel that oversees Danny's spree of vengeance.* In the book, which is all through George's perspective, he sees her first: "She had the natural-seeming poise of the professional model, and moved with a grace that survived the haste of her passage down the stairs. George stared at her with a vague lust." Priest's George gets more of an eyeful before his awkward introduction to Simone, and it's sort of unavoidable that Priest gets into his realization of Simone's "style, quality and innate class," how she's too good for him, and that he "fancies" her too quickly - all of that is introduced within the second paragraph after he sees her for the first time. The development of their relationship lacks the subtlety of another great little seemingly-improvised moment from the movie that isn't in the book, shortly after they've gone from not being able to stand one another to becoming something of an oddly cute couple, with George in adorable gentle pimp mode as he grooms a grinning Simone at the hotel and reassures her, "Got to look our best." Simone seems colder and even less accessible in the novelisation, to the point that she's kind of lost as a character; it kind of works though because the book is all about George and his inability to figure her out. To make this even more explicit, Priest includes exchanges like this chapter-ender:

George: "I thought you were high class and respectable."

Simone: "Whatever gave you that idea?"

George: "I dunno. I always seem to get things wrong."

George's unrealistic expectations for Simone to be something she never claimed to be couldn't be more flatly stated; like Fergus' reaction to Dil's pickle in The Crying Game - You didn't know I was a cross-dresser? Then why'd you seek me out in a gay bar? - George simply isn't aware how the game is played or even why he's playing ("Sometimes love is a strange and wicked game" was the tagline for Mona Lisa, 6 years before Jordan's international hit.) And like Fergus, a bemused George can only witness in horror the climactic one-sided gunfight that mirrors the one in The Crying Game as romantic notions (running off to Brighton) give way to an emotional catharsis (revenge) he never predicted would be the natural culmination of events. At the end of the movie George narrates himself as being the "sort who couldn't see what was in front of his face," some serious retrospective introspection from an ex-con introduced as being blithely ignorant of why his wife wouldn't want to have anything to do with him, why turning up on her doorstep with flowers isn't the smartest move, or why the Hawaiian shirt under bomber jacket with gold chain look is the complete opposite of class. He rejects the revelations at Brighton by hiding behind a pair of cheap novelty sunglasses indicative of his own na´vely-filtered, childlike perspective of the world - one with couples walking arm-in-arm and having lit'l ba-bees - and it's removing them that gets him to snap into action. As Chapter 26 in Priest's book opens with a razor blade-wielding Anderson bearing down on the two of them on the pier (something a star frame-bespectacled George literally doesn't see until Simone screams warnings at him), he relates that "George had a moment of clarity, an instantaneous flash of perception" that allows him to take control of the situation and get Simone to safety. For Priest to pinpoint that moment with that precise phrasing - he knows the Brighton sunshine is good for the ol' perspective. George has spent the film/book opening doors: after having the first one at his old home slammed in his face, his newfound quest for understanding leads him to the slit in a door at the strip tease; he breaks down the door to Simone's hotel room to find her in a compromised position; he sees Kathy and the old creep through the door (via two-way mirror) at Mortwell's and finally enters the hotel room in Brighton to the sight of Simone and Kathy in bed together. None of these offer any real understanding, their indoor-ness innately confining. George is open to understanding: the first shots of the movie have George near bodies of water - crossing a bridge, sitting quietly on a bench by a pond, notably alone - but going from these calmer, less extravagant waters to the unpredictable ocean is like going from 0 to 100. Blowing up at the beach was as inevitable for him as a final confrontation with Mortwell and Anderson was for Simone.

Going into the novelisation, there were a few things left ambiguous or unanswered in the movie that I was curious to see if Priest would address: why George was in jail, whether or not Simone's relationship to Cathy was really a romantic one, and what the deal was with that rabbit. Priest's version implies a lot more of George's criminal background than the film - although Priest never offers specific details of his past activities, he describes him as a gofer and makes clear that his main function was more or less what it is in the movie, to drive. When he's tailing Anderson, Priest reveals: "He had always been paid for his driving. A top driver was what he was, or what he had been when he took the rap for Mortwell." George later has a memory of driving Mortwell to his house, with Mortwell ordering him to park in a lane around the back, which suggests whatever the set up was that had George taking the fall for his boss. When in Brighton, George has another flashback of an earlier trip to the shore for a job he'd been part of back in the old days; whatever went down there resulted in a watchman being shot, and Priest states that Mortwell tried to set up George for the shooting: "That was the first time, and he had had the wit to see it coming." So Priest, while recognizing that George was always viewed as an expendable part of Mortwell's operation, also saw him as being muscle for Mortwell, as Jordan had suggested by George's savage beating of the pimp on the bridge in King's Cross. In that scene in the book, the pimp is described as having "the sort of face it was impossible to kick just once" and George's brutal efficiency is implied by the great sentence, "There was a cracking sound, so George hit him again." Of course the pimp beatdown sets up the incredibly satisfying moment in Brighton where Hoskins turns into a little incredible hulk and head-butts and kicks everyone, but I always thought the implication in the movie was that George is a little scrapper who can handle himself in a fight as opposed to a professional badass bruiser with an instinct for trouble; it's what separates him from someone like the sociopathic Anderson. I think Priest would more or less agree based on his approach to the character, although he has George boldly going to Mortwell's to find Cathy with what he calls a "new lucidity," a confidence that makes him seem like a cool, collected assassin-type criminal more than a gofer, although Priest clarifies that this sudden sangfroid "was to do with being sure; it was also something to do with the gun in his pocket."

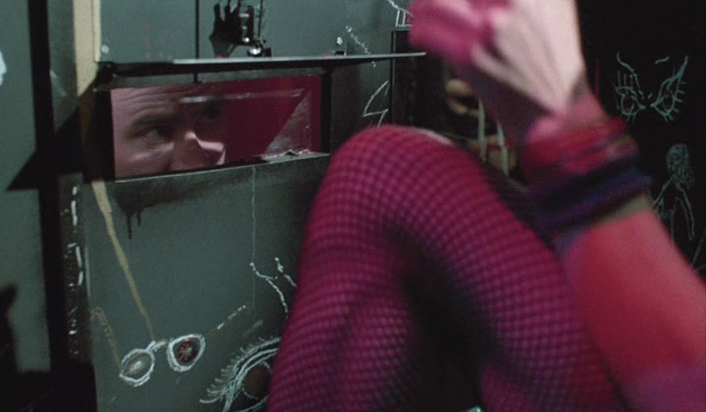

I guess that's fine: George is an ex-con who knows only fellow criminals, he couldn't possibly be totally ignorant of the nature of illegal activities. However, George should not know what to expect to find in Mortwell's house, a point in which Priest kind of slips by stating, upon George entering his boss' fancy sex cauldron and looking inside the private room closets, "All this George had seen before." It's the sordid details of Mortwell's "perfickly legal" venture into vice that vex George most distinctly, that he is consistently awed and repulsed by, like the sight of a young prostitute wearing a schoolgirl uniform who Priest classifies as a "parody of a parody, a girl disguised as a woman diguised as a child." It's one thing for Priest to have George suddenly switch into ass-kicking mode, but to have him shrug off the scene at Mortwell's feels like he's writing about a different character entirely. Again, it's really something you have to see in Bob Hoskins' face, the nearly indescrible discombobulation that registers as he tours the seedy world of the skin trade, like Stephen Rea's exhausted expression as Danny, sadly experiencing firsthand the grim inhumanity of the criminal underworld. Clearly it was a challenge for Priest to capture George's childlike befuddlement as he's touring the sex shops without the visual aid of Hoskins - or the audio aide of Genesis** (although there's no "In Too Deep" in the book, there is an added line where Simone assures George that he's as much a part of the sex business as she is, that he's "deep in it" - I like to think Phil Collins somehow read the novelisation and was inspired by that line to create the song for the movie.) He also does away with some of the confusion that sets George off on the Brighton pier by having him walks in on Simone and Cathy at the hotel in a much more compromised and explicit position, "one hand delving deep into the softness between Cathy's legs," "kissing gently on one of her nipples," while "Cathy was asleep...or unconscious." Now, one could argue that Jordan didn't intend Simone and Cathy's relationship to be ambiguous at all, but I'd say he presents it vaguely enough in the film that George could be misinterpreting a complicated, intimate relationship as one of an intensely sexual nature. Obviously not in the book, where he rightfully accuses her of "playing finger pie with a bombed-out teenage whore." Priest's blue phrasing (he also moves George and Mortwell's second meeting from the dressing room to the main area of the club, where he describes the "expert, economical movements" of a solitary stripper slinking around in the spotlight of the empty stage) ties the conclusively lesbian couple to the sleaze surrounding Simone's nighttime activity, particularly a much more graphically depicted scene of George bursting in on Simone at the fancy West End hotel room and watching in horror as "a streak of silvery semen dribbled across her taut stomach, filtering wetly into her pubic hair." The view that George witnesses through the mirror at Mortwell's is also much raunchier in Priest's book, although I'll spare you the details - suffice to say, if Hoskins' George had seen the same things as Priest's George, had probably would have lost his mind.

Now I know the movie was limited in the amount of finger-pieing and semen-dribbling it could show onscreen (at least outside of an unrated director's cut), but even so Priest's spicing up of these scenes seem like he wanted to give George a little more credit, as if to say 'sure he's seen dildo hats and kinky lingerie before, he's not an idiot - it's just seeing them in practice that shocks his sensibilities.' Well sure, and being in prison for seven years would suggest he's no stranger to homosexuality either...it just speaks for the cinematic achievement of these characters that what we understand about them intrinsically from watching them is so difficult to convey on the page. For example, I never questioned how George knew Thomas: Hoskins and Robby Coltrane have a natural chemistry that settles the viewer right into their "nice to see you after seven years, need to come live in my garage?" friendship. Thomas is another aspect of the movie that's made immediately coherent by the mere presence of Coltrane, but in the book you have to seriously wonder whether or not he's supposed to be even more antisocial, if not borderline retarded. He gets George a gun and knows Mortwell, but doesn't seem to be directly involved in any current criminal ventures; Priest even points out that he disapproves of weapons, so he's presumably out of the thug life? Apparently he's just able to sustain his lifestyle as an independent entrepreneur: the book keeps the ornamental spaghetti - "The Japanese have cornered the market!" - but leaves out the fibreglass fruit fly and porcelain tutti fruitti. The novelisation also misses details like Thomas having a Mona Lisa print on his fridge, and unfortunately doesn't expound any further upon Anderson living in a room with a paraffin heater - I always thought that was a pretty weird detail for Simone to bring up. We never see much of Anderson's personal life, he's all business, but you can kind of see him living sort of the opposite of Thomas: a modest room with just his suits, his knives and a paraffin heater (unless he shot that porno with Simone in his own apartment - by the way, it's hard to see the video box in the movie but apparently the porno is titled Kactus Kitchen? Sadly the book doesn't clear this up by ever mentioning it by name.) In one of my favorite of Priest's touches, he uses the word "evil" to describe the blade of Anderson's razor; he also writes that Thomas "revealed that he slept in a pair of underpants that looked extremely evil." Anderson's razor attack on George and Simone in the elevator is more played up and suspenseful in the book: Simone recognizes Anderson's car parked on the street, Anderson's assault takes them by surprise more because George is distracted by Simone and it goes on for a few pages with the lift going up and down as Anderson hurls bottles through the cage doors to show that he's not just appropriating Michael Caine's razor-in-elevator murderous operandi from Dressed to Kill. As for Caine, his unique representation of oily sleaze is impossible to imply with the printed word (as I'm sure the author of the Jaws: The Revenge novelization would sympathize - he had to make Caine's character a drug dealer to give the reader a hint of additional smarm). As with George/Hoskins, Priest doesn't even try, opting to avoid physical description in favor of telling actions: "He winked broadly at George, and raised a hand, a mocking wave. George did the same. Each mocked the other." He does describe the shiny black leather chair shaped like a giant hand*** that Mortwell sits in at the club: "As George walked up to him, he couldn't see the thumb, and he wondered where it went to." Priest plays up the idea of Mortwell as a bully-father to George, literalizing the gangster's insistence that he's the head of George's "family" with the flashback to the Brighton heist, prior to which Mortwell insisted the crew "go on the Dodgem cars, shoot pennies into the games in the arcade, wear seaside hats." George joins other Neil Jordan lead characters who'd like to see the father figure dead: Jimmy in The Miracle (Oedipal dreams of Sam burning to death), Louis in Interview with a Vampire (resentful/homicidal attitude towards sire Lestat) and Mick in Michael Collins (antagonist relationship with older mentor ╔amon de Valera). But like them, George's conflicted feelings make him unable to act on the impulse - like Claudia in Vampire, the girl's the one who pulls the trigger, and Mortwell ends up slumped into a corner with the ominous rabbit George had previously delivered licking the blood off his hand.

What is the deal with that white rabbit? It's obviously another Bardin-esque detail: in place of a percheron George delivers a rabbit, which Mortwell then creepily decides to bring along for the final confrontation in Brighton. The inexplicable leporid bookends the narrative that George has created for himself which ultimately breaks down as the rabbit hole caves in around him: the simple formula of mystery stories are easy for him to figure out, but like his old-fashioned ideals lack the intricate twists and complexities of real life. His own version of the romantic tale of the noble "tall, thin, black tart" starts to fall apart when Simone's attentions turn unexpectedly to the rescued Cathy, creating a rift that continues right up to the Brighton breakdown as if George's fantasized story were suddenly riddled with glitches. This narrative "hiccup" is set off via a series of repetitions that occur right after George escapes Mortwell's with Cathy: in George's Jag, she sings the infinitely recurring song "Michael Finnegan," itself a perpetual repetition that's further mirrored when married to the transiting shot of a structure in the shape of a giant shoe - "There once was a man named Michael Finnegan"/"There was an old woman who lived in a shoe" - at the Happy Eater diner. Confining in Thomas, whose presence in the film has been almost spectral - he turns up right when George needs him following his violent fit outside his ex-wife's townhouse and, beyond a very brief meeting with Simone, is completely divorced from the main plot and speaks only with George - George informs him the introduction of Cathy has made things complicated. "More complicated than the story about the horse?" Thomas asks. And once Thomas pulls away in his car, the scene ends with a giant horse appearing surrealistically right in front of George (there's no horse in the book - Thomas' line is "More complicated than The Deadly Percheron?") The sight of the horse connects what's happening to George with the events of the Bardin novel, although it's more a sign of the fantastical elements of his story leaking into the real world. Earlier in the film (and book) he'd attempted to clumsily relate to Simone the tale of the frog prince (itself connected to the twice-related/bookending frog fable from The Crying Game) as a parallel to their own situation without her taking the hint: sorry George, you're not scoring an enchanted snog. Possibly prompted by his "new lucidity," George forces his fairy tale into reality by spiriting sleeping beauty Cathy away from the evil dungeon almost magically, through a one way mirror, making it seem to her elderly john as if she's disappeared into thin air.**** He brings her to meet Simone at the diner where more repetitions take place in the reflection of earlier dialogue, like Cathy echoing Simone's earlier concern for George's ability to comprehend what's going on:

Cathy: "You don't know anything, do you?"

George: "No...no, I don't know anything."

Both Simone's and Cathy's question/statements were also expressed by Mortwell, who crafted his own repetitious question/statement monologue the first time he summons George to the nightclub: "Do you or do you not get confused? You still get confused. Well at least now you know - you do know it, don't you George?" (another repetition: Mortwell telling George he wants him to be happy, just as May does when she's awkwardly trying to seduce him). Priest gets in on this action, not only including these further examples of matching sets of repetitions from the movie's diner scene in the book...

(sitting in the diner)

Cathy: Do you like me?

George: I don't know you, do I?

(sitting outside the diner, re: Simone)

George: You like her, don't you?

Thomas: Do you?

George: I don't know her, do I?

...but also having this be the final exchange of the novelisation, again with George and Thomas talking about Simone:

"But you liked her George...you really liked her."

"Nah." George drove through Highgate Village, then took the side road towards the Heath. "I didn't know her, did I?"

Which is just as much a revelation for the character as coming to terms with being "the sort who couldn't see what was in front of his face," the closing of George's "book" that didn't end up in Priest's. But bringing the word "like" back is kind of ingenious: it reminds the reader of the childlike na´vety George shares with so many of Jordan's male leads that his trip to Brighton has helped him get past. Whether the reaction to what they learn at the seaside is positive or negative, Jordan's characters grow from their experience at the Portstewart resort in Angel, the circus in The Miracle, the carnival in the first scene of The Crying Game (technically not the seaside - it appears to be straddling some kind of river or quarry, but its proximity to water is still notable), the children's entertainment center and boardwalk magic show at Southend in Breakfast on Pluto. The beach is where childhood idealism dies, and the characters can either accept it or not: as Fergus refers to 1 Corinthians, it's the place where they must put away childish things. Like the junkie girls who demand ice cream, George reverts to a child on the Brighton pier, demanding some Brighton rock in a grotesque display that's also a cry for simple solutions and an effort to tune out the complexities of the adult world.***** He'll ultimately abandon Mortwell, the absent father, and Simone, the mother he's trying to impress, ready to accept responsibilities as a parent to his own daughter.

As I mentioned, the ending of the novelisation differs slightly from the movie. It actually ends more like The Crying Game: George has just visited Simone in jail, their unconventional relationship in stasis by the convenient plot resolution of one of them being behind bars. I didn't realize until comparing the film and book's endings that the last scene in the film is open ended - in fact, George telling Thomas the end of his story could even be a flashback, the implication being that leaving Simone to her fate in Brighton is the last chronological event of the movie (thus negating the last sentence of my preceding paragraph). However that impression is probably just based on the whimsical "happy" tone of Jordan's ending, almost like fading into a dream, the haunting shot of Simone in the rearview of the Jag, so close yet completely untouchable, framed in glass like the famous painting itself, an indelible image to leave the viewer with. The dream of Simone brought to George's doorstep may have died there in Brighton, but if the last scene in the garage is in fact the final act of Mona Lisa George is better off for his experiences, left with the two people (Thomas and Jeanie) who don't think him a mug. Priest's ending represents the same idea, but reminds you that, besides the performances of Hoskins and Caine and the character of Simone, the thing most glaringly absent from the novelisation is, simply, Neil Jordan. His uncanny knack for infusing straight stories with fantastical, dreamlike touches is something that the director himself can't perfectly replicate in prose, making me wonder whether Mona Lisa is just too good for a novelisation (as opposed to say Krull, Oh Heavenly Dog! and, yeah, Short Circuit). Priest's book version is very readable, but for all his qualifications as a science fiction writer he never quite captures the chimerical reflection of George as he exits the Royal Albion, leaving Simone behind, walking parallel to the water on the promenade.

* In addition to Chris Priest's Dream of Wessex, Sphere also released the U.K. editions of such novelisations as George Romero & Susanna Sparrow's Dawn of the Dead - which has to be one of the few novelisations to be reprinted three decades later - and Donald F. Glut's The Empire Strikes Back. (I should mention that Glut, despite writing, directing and providing voices for hundreds of animated shows, is listed on Wikipedia as being "best known for writing the novelization of the second Star Wars film.")

** Is there any 80's movie not marred by 80's music? The novelisation of course does not mention Genesis; however, the last scene of the book has Thomas and Jeanie forcing George to switch off Nat King Cole in favor of "Here Comes the Sun." I'm convinced this is from the original script, since David Leland was a close from of HandMade Films co-founder/Mona Lisa executive producer George Harrison. But I'm glad it didn't end up in the movie.

*** I never thought of it before, but was this prop a reference to Michael Caine being in The Hand?

**** Not my observation - I picked that up from Matthew Dessem's exceptional (and ambitious) Criterion Contraption blog.

***** Priest again: "(George) walked down to the beach, and clattered across the shingle to the sea's edge. Here he turned his back on the waves and looked back across the town: he saw the lights from streetlamps, windows and signs, and the moving brilliance of traffic, but the sea sucked up all the noise from the town so that it seemed to exist in frigid silence."

RELATED ARTICLES

<<Previous Page 1 2 Next Page>>

home about contact us featured writings years in review film productions

All rights reserved The Pink Smoke ę 2013