a pink smoke easter special

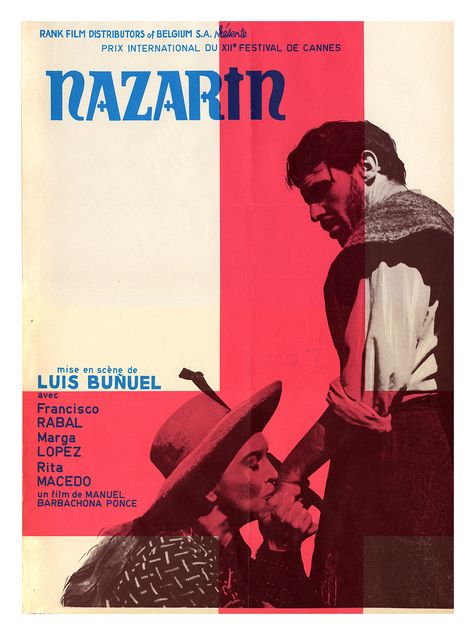

NAZARIN

luis bunuel, 1958

~ by john b. cribbs ~

"I'm an atheist, thank god" has become, for lack of a better word, the catchphrase by which audiences even scantly familiar with Luis Buñuel's films have come to reduce the rather significant impression he left on cinema. It's a shame, because while the quote does capture the kind of simple, playful irreverence and deceivingly contradictory sort of message the director is known for, it also relegates his exceptionally complicated thoughts on religion and

its

fundamentally beguiling effect on humanity to a one-off witticism. Buñuel himself later regretted allowing the phrase to become the butt of academic shorthand for easy categorization of his work as sacrilegious farce without any of its artistic or intellectual merits attached. He can't be blamed - at the time he said it, it actually meant something to take an opposing position to the Church, but as the 60s took a foothold in cultural beliefs and world cinema

was flooded with films that drew very specific political and religious lines in the sand, the director couldn't expect riotous receptions like the one L'age d'or met in 1930. The result of Buñuel was that, by the time he released The

Milky Way in 1969, attacking Christianity on film had become so outmoded it was actually

the most unexpectedly blunt move on his part to make a film that did exactly that. The unfortunate downside is, when the hero of the movie fantasizes about the pope being executed, it's the kind of thing that causes people to nod and note dismissively, "Yep, that's Buñuel for ya." Judging that moment on its own is to miss the gun being turned on itself, the brilliance of taking the concept of martyrdom - such an establishment of credibility in Catholic history

- and making it seem like the seditious suggestion of a philistine...which, at the same time, is exactly what it is! But I constantly worry that people think only of the "controversial" Buñuel and take scenes like these as nothing but provocative baiting of conservative religious types, as reliable as John Landis having his lead wiseass break the fourth wall or Kevin Smith making a Star Wars

reference. People take for granted that Buñuel hates religion - he does, but that's not the beginning and end of it.

I think this general misunderstanding of what Buñuel's about is partly to blame for Nazarin being such a tough sell to critics at the time (it might still be today) and its unexpected acceptance among parties who really should have felt the most scathed by it. Renata Adler's confused 1968 review for the New

York Times called the film "grim" and "relentlessly pessimistic." French newspapers thought the movie carried an evagelical message, political reviews declared it a flagship for anticlericalism, yet it was nearly awarded by the Catholic church(!) At the same time, the film was a huge hit: it won the international prize at Cannes and allowed Buñuel to return to Spain and make Viridiana, in a lot of ways a sister film to Nazarin

which nevertheless received much more one-sided contemptuous responses - although it was awarded the Palme d'Or, it was denounced by the Pope; Bosley Crowley called it "an ugly, depressing view of life" (was it just because the idea of a woman "rotten with piety" seemed more slanderous and perverse than what was seen as a parody of the life of Jesus?) Like Viridiana, the ineffective priest Don Nazario is a character acknowledged as having a "heart of gold" yet often described

in so many words as "a little nutty" in the same breath, his attempts to spread Christian goodness to the heathen masses of turn-of-the-century Mexico as misdirected as the former's attempt to rehabilitate a group of wretched street urchins to some form of Christ-endowed civility. Both films, each respectively based on a novel by Benito Perez Galdos, feature one spectular Buñuelian moment - Virdiana the corruption of the image of The Last Supper,

Nazarin a portrait of Jesus laughing mockingly at a wounded, hallucinating prostitute - but are on the whole much more grounded in reality than some of the director's other famous films, although he can't resist throwing in the voice of Nazario chanting "mea culpa" and a creepily adult-sounding boy being spanked outside to compliment the savior's smiling visage. The Jesus image is the only real example of surrealism in Nazarin, its humor is more harsh and less broad*,

its setting in the days of Porfirio Diaz's dictatorship arguably the closest Buñuel came to depicting life under Franco. Finally, although the film reflects the kind of cruelty that existed around the time of Diaz and his tyrannical "pan o palo" policies, that specific government doesn't play a part in the story, so like Viridiana it's not readily apparent exactly who the director's satirical target is.

I think this general misunderstanding of what Buñuel's about is partly to blame for Nazarin being such a tough sell to critics at the time (it might still be today) and its unexpected acceptance among parties who really should have felt the most scathed by it. Renata Adler's confused 1968 review for the New

York Times called the film "grim" and "relentlessly pessimistic." French newspapers thought the movie carried an evagelical message, political reviews declared it a flagship for anticlericalism, yet it was nearly awarded by the Catholic church(!) At the same time, the film was a huge hit: it won the international prize at Cannes and allowed Buñuel to return to Spain and make Viridiana, in a lot of ways a sister film to Nazarin

which nevertheless received much more one-sided contemptuous responses - although it was awarded the Palme d'Or, it was denounced by the Pope; Bosley Crowley called it "an ugly, depressing view of life" (was it just because the idea of a woman "rotten with piety" seemed more slanderous and perverse than what was seen as a parody of the life of Jesus?) Like Viridiana, the ineffective priest Don Nazario is a character acknowledged as having a "heart of gold" yet often described

in so many words as "a little nutty" in the same breath, his attempts to spread Christian goodness to the heathen masses of turn-of-the-century Mexico as misdirected as the former's attempt to rehabilitate a group of wretched street urchins to some form of Christ-endowed civility. Both films, each respectively based on a novel by Benito Perez Galdos, feature one spectular Buñuelian moment - Virdiana the corruption of the image of The Last Supper,

Nazarin a portrait of Jesus laughing mockingly at a wounded, hallucinating prostitute - but are on the whole much more grounded in reality than some of the director's other famous films, although he can't resist throwing in the voice of Nazario chanting "mea culpa" and a creepily adult-sounding boy being spanked outside to compliment the savior's smiling visage. The Jesus image is the only real example of surrealism in Nazarin, its humor is more harsh and less broad*,

its setting in the days of Porfirio Diaz's dictatorship arguably the closest Buñuel came to depicting life under Franco. Finally, although the film reflects the kind of cruelty that existed around the time of Diaz and his tyrannical "pan o palo" policies, that specific government doesn't play a part in the story, so like Viridiana it's not readily apparent exactly who the director's satirical target is.

Is it Don Nazario? Does Buñuel hate priests? On the surface, the answer seems to be yes: Buñuel portrays him as a holy fool, a Quixotic pilgrim stubbornly charging at spirtual windmills. If that's the case then who exactly is Buñuel sympathizing with in the movie? Certainly not the military official who forces the peasant passing by on the road to

acknowledge his superiority, or the political heads of the Catholic church who defrock Nazario. Not the ditch diggers who see the priest's offer to work for food as setting an unfair precedent to their slipshod union and run him off, setting off a violent labor dispute. And certainly not Beatriz, the suicidal nymphomaniac, or Andara, the "hideous" hooker, the only two people who choose to worship and follow Nazario, and for all the wrong reasons. No - just as Cervantes wrote affectionately of his

wayward Man of La Mancha, Buñuel admires his title hero as a man who lives by ideas that are unacceptable in his time and place, despite how stubbornly he sticks by them or how antiquated they are. In the words of Octavio Paz, Nazario's madness "consists in taking seriously great ideas and trying to live accordingly." He is a man out of time, a hopeless idealist whose precepts of virtue among the unenlightened are (rightly) considered

outdated by those he tries to convert and (humorously) blasphemous by the heads of the same church that supposedly advocate the same basic ideoologies. In that sense, Buñuel almost seems to respect him as a fellow heretic.

On the other hand, this man is an idiot! He's as sanctimonious and judgmental as any man of the cloth. He invites the constant theft of his house, the stoning of his person by irritated townspeople, and refuses an offer to escape arrest which may result in his execution. And if Buñuel isn't attacking Nazario and his beliefs, doesn't that mean

he condones them? I guess what I'm saying is that it all comes down to is what Buñuel thinks of Jesus. In his depiction of the real guy in The Milky Way, Buñuel's ideas on enlightenment are expressed in the final scene where Jesus heals the two blind men, but doesn't stick around to help explain what it is they're seeing. He doesn't have time to show them "black" and "white" as they

insist. One of them shouts that he can miraculously hear a plane passing over (transporting Simon of the Desert to the nightclub perhaps?), even though he could hear perfectly without his newly restored sight. In the last shot of the movie the men follow Jesus' posse, who easily step over a small ditch, and use their walking sticks to avoid stumbling: again, relying on themselves and the discourse of their original handicap rather on this heaven-sent gift. It's less obvious yet just as effective

as what is possibly the 'smoke's favorite Buñuel moment of all time: the handless man who slaps his son upside the head when Simon of the Desert restores his missing appendages. In these instances, it's not so much hyprocisy as the consensus that miracles come and go, but it's still just another day. Nazarin has its own hybrid of the characters from those two films: a blind beggar who supplements himself

to beg money from the priest, yet out of earshot doesn't hesitate to give his daughter a good smack when she talks back to him.

That covers Buñuel's opinion of the deified messiah and man's reliance on religious magic only so far as it will help him in carrying out his day-to-day existence, but throughout Milky Way he also shows Jesus as a man: out of breath after running, maintaining his trademark "iconic" beard only because his mother says it looks good on him. This is clearly an image of Jesus in

contrast with the church's mystical rendering of him, and it allows Buñuel to access his celebrated aphorisms without the divinity. Famous parables with messages like "turn the other cheek" and "love thy enemies" can then be considered based on whether they're being exercised in the name of social justice or exploited for personal gain. In order to make a clear distinction between what man takes from Christian doctrine, in Nazarin Buñuel had to

cast as his hero the best possible Christian, a Jesus figure, one who models his life so archaically close to Christ that he allows even his most essential possessions (food, clothes) to be taken away and, after losing literally everything including his home and his job, peregrinates the land poor and shoeless. Like Viridiana with her coarse linens and crown of thorns, he embraces this antediluvian style of genuflection even when doing so threatens his personal well-being. Unlike Christ, Nazario is never

seen preaching and fails to attract a following beyond the two delusional groupies who tag along on his "mission." Buñuel even strips Nazario of the political importance of the historical Jesus** to make his seem even more a fool's errand. Nazario's not trying to shake the tense political and religious situation in Jerusalem, he's just been implicated in the burning of the inn he was staying at and is sort of an indifferent fugitive. The obvious thematic

question this raises is what place a Jesus figure would have in the modern world, but what Nazario's impotence as a spirtual leader sets up is the wayward priest's own crisis of faith. Buñuel wants to guide him to a resolution of this crisis in a way that's part sympathetic and part critical, although never outright condescending. Whether it's showing Jesus in front of the shaving mirror, or whisking Simon away to the Devil's nightclub, Buñuel is less interested in castigating

these individuals based on their beliefs than he is in liberating them from their repressive sanctity, which he just happens to do by wearing down their defenses against the most corporeal temptations.

So if he wasn't specifically looking to take the Catholic church down a notch through the tale of a religious idiot, what exactly was Buñuel's plan with this movie? That he wants to "save" his characters hardly sounds like the agenda of "an atheist, thank god." A more applicable quote, at least towards understanding his heavily theology-slanted narratives and this film in particular, is one from Buñuel's

autobiography: "Belief and lack of it amount to the same thing." Because if there is one thing Buñuelis unquestionably into it's human behavior, from whence the sex and crime and perversion that fuel his obsessions flow, and he is equally interested in the piety of the righteous and the vulgarity of the wicked. This informs the penultimate scene of Nazarin, in which the incarcerated and bullied former priest tries to convince a fellow prisoner who's saved him

from being beaten and raped that the prisoner is a good man. The prisoner assures him that he isn't, saying "You're on the side of good and I'm on the side of evil, and neither of us is any use for anything." Nazario is devastated by this declaration, more or less a paraphrasing of Buñuel's quote, and appears broken by its nihilistic implications. Already confused over his sudden inability to distinguish "contempt" from "forgiveness" when his cellmates turn on him, the incarcerated

priest is utterly, figuratively grounded by this introduction of adiamorphic equalization. Nazario's chaste life and the prisoner's sinful one have landed them in the same place, on the road to further misery and uncertain fates. That an admitted criminal, one who confesses to having robbed a number of churches and doesn't even consider those crimes to be the "bad things" he's done, could nevertheless risk his life to save a fellow man, is an unfathomable

paradox that the priest can't bear to sort out in his head. It's also an example of a side of Buñuel many don't consider, the humanitarian half that prompted the small moment in Viridiana where one of the beggars sneaks food to the "leper" the others have collectively scorned and set away from the rest of the group. Another interesting connection between the two films: when the prisoner moves to defend Nazario he whips out a concealed

blade in a movement reminiscent of how the beggar who intends to rape Viridiana brandishes his weapon. Both are unintentionally setting off the moment that will resign the hero to a life removed from god, even though one is defending the conflicted party while the other is attempting to hurt them.

The conversation between Nazario and the prisoner, as well as the theme of rejecting salvation in favor of earthly needs, is something Buñuel borrowed from Dialogue Between a Priest and a Dying Man, an atheist polemic written by the Marquis de Sade in 1782 and published in 1929 (Sade comes up a lot in the director's filmography: his

writings and "imagined crimes" inspired The Criminal Life of Archibaldo de la Cruz, Michel Piccoli portrays Sade in The Milky Way etc.) The dialogue is between an unrepentent libertine on his death bed and a priest attempting to administer last rites - the dying man succeeds in convincing the holy man that since there is no evidence to prove god's existence it's wrong to devote one's life to piety and virtue,

ultimately paraphrasing of the Golden Rule - "render others as happy as one deserves oneself to be" - an ancient maxim which Matthew attributed to Jesus despite its dating back to the parable of The Eloquent Peasant as early as 2040 BC. The writing is referenced directly in a scene where Nazario tries to provide the same final ministrations to a woman who may be dying of the plague in a small town. The woman ignores him, crying out for her lover Juan ("Not heaven - Juan!") and,

when Juan finally arrives, insists he make the priest leave. Nazario sees this as a failure since he was unable to convince the woman that salvation is better than taking comfort in the presence of her boyfriend, and Buñuel, like Sade, uses it as a victory to expose the ultimate fault of a pious priest, so quick to send us away to paradise, ignorant to our earhtly concerns. Nazario is at odds with the secular and the spiritual throughout the film as he attempts

to satisfy an impossible balance between faith and superstition, insisting that miracles are unrealistic while maintaining the aura and omnipotence of an all-powerful deity. Andara is constantly asking seemingly ignorant questions that are completely logical: the belief that three buzzards bring bad luck truly isn't any more absurd than the idea that giving money to priests save people's souls. To draw an honest rationale between the two is to lose the sense of heaven, which is the last thing Nazario wants

to do, although it brings him nothing but grief. When he's called upon to "heal" a sick child, he tries to escape the family's claims of his sainthood with the highly contradictory line "Only God and science can help her." But he's trapped by his own beliefs to perform the "miracle" of saving the child (who, it's established, has just recently been administered medication) - although his reluctant prayers turn to a mocking travesty as he watches helplessly as women

in the girl's family writhe in religious ecstasy on the floor, he can't claim this to be a failure similar to the plague victim, although it's clearly a disaster. These women accept his license to carry out the lord's work yet take it to such a blasphemous extreme that the scene could represent the beginning of any of history's great debacles that stemmed from religious fervor. It's not the gospel Nazario wants to teach, but the alternative is a woman who refuses her last rites in favor of her lover's arms.

Whether someone believes in god or not - "illusion or futility" as Sade's dying man put it - is not as important a concern as whether man has any use for him.

Nazario's unreceptive flock don't have much use for god at all. These people don't need enlightenment, they've got brand new electricity being installed at the inn! In the plague village they don't need priests, they need medics! Even the church has evolved past his "insolence" and "follies," even though they are strictly in keeping with Catholic dogma. Life

at the beginning of the twentieth century has progressed beyond the need for blessings and selfless charity; most unfashionable is the ideal of unconditional love. Beatriz and Andara cause most of Nazario's problems, especially in the third act when Beatriz's boorish boyfriend Pinto stirs up authorities to arrest the travelers and Andara's admiring dwarf follower Hugo becomes the trio's "Judas" and gives up their whereabouts. The village is completely willing to accept Andara

as a street walker (albeit it a "hideous" one) yet get themselves riled over the idea of a man in the company of two women, even though they also have no problem with Beatriz's relationship to the cruel and bullying Pinto. Beatriz is psychosexually tortured, indulging in sadomasocistic fantasies*** that send her into violent fits, which she refers to as "spasms of the heart." Repressed into a waking state of full-blown delusion, her only course is to believe that her carnal urges are akin

to religious devotion, a fallacy that's crushed when her mother points out she loves Don Nazario "as a man." Buñuel's use of Beatriz to examine a woman being pulled away from a chaste life by a brute who wants to use her for sex must have informed the character of Viridiana, whose dilemma is not to fend off her own base urges but to somehow find a loophole in which consensual depravity could be considered a form of selfless charity. For both, Buñuel presents it as going

in one extreme direction or the other, celibacy or hedonism. Viridiana's is basically, "Oh, I'm unworthy to serve God? Then I might as well debotch myself and enjoy a threesome with my cousin!" In fact, in the context of their later collaborations, Buñuel's most retroactively insolent act would be casting Francisco Rabal, who would represent the sleazy secular world Viridiana surrenders herself to at the end of that

movie, as the holy Nazario. Pinto and Virdiana's Don Jorge are basically the same character, lulling the ladies further away from their fanatical devotions to god (although Pinto's method of seduction is one suited to woo a woman with her own sexual hangups.) Not that outside interference is entirely to blame in the case of Beatriz and Andara: the latter is jealous that Nazario might prefer Beatriz and moans unconsolably despite the priest's claim to love both women equally. Amusingly, he seems most

enamored of a slug he's placed on his hand as his two companions quarrel over who he loves best. Buñuel goes out of his way to show that life with Pinto is not a healthy option for Beatriz, but doesn't hesitate to point out that a deluded life of misguided hero worship is hardly the place for her either.

These characters are bound to earth, which is why Buñuel structures the film after anti-transcendental Spanish Picaresque literature, a form he'd continue to experiment with and come closer to perfecting in The Milky Way. Like the galley prisoners who turn on Quixote despite his defense of them, everyone Nazario tries to help - Andara and her fellow prostitutes, the construction foreman and his workers, the plague victims,

Nazario's fellow prisoners - instantly despise and ridicule him. Like the bawdy occupants of Picareseque novels, they're presented as colorful and hopelessly corrupt so that Buñuel can maintain an objective view of the kind of torment Nazario subjects himself to without coming off as cynical and misanthropic, two other words that have been thrown around over the years in discussions of his work. In the words of Andre Bazin, discussing Los Olvidados, Buñuel's "cruelty evades nothing, concedes nothing,

and dares to dissect reality with surgical obsenity... Paradoxically, the main feeling which emanates...is one of unshakable dignity of mankind." Buñuel really does love humanity, warts and all, and fully detests anything that gives a man a dreamed-up authority to feel like more than he actually is. This is the quality he loathes in the officer who humiliates the man on the road, sanctimonious figureheads of the

Catholic church,

rich hypocrites

who look down on everybody else. Buñuel's goal in Nazarin is to exorcise this notion from his hero's head, even though he is technically stripped of the surface titles and arrogance that make the kinds of characters I just mentioned such easy targets. Buñuel doesn't want to say "this is a good and righteous man who was unjustly met with derision and hatred" - he wants to take that basic theme of the Jesus story and turn it into

"this is a backwards and confused man who needs to understand that there's just nothing you can do. We are who we are, and nobody has the right to claim otherwise."" Buñuel doesn't hate Nazario for his beliefs, nor does he love him for his convictions - just as he wanted Simon off that pillar, he wants Nazario where

he belongs, down here on earth withthe rest of us.

The final scene is of Nazario being marched away alone, the church having formally distanced themselves from his actions and Beatriz resigned to go away with Pinto. Nazario is spirtually naked, having been hollowed out by his dialogue with the prisoner who saved his life. When the armed guard stops for some fruit, the vendor offers Nazario a pineapple. The shocked priest initially refuses the charity, although visibily torn between hunger and the kind of stubborn

fasting of worldly materials he's maintained throughout the film. Ultimately he accepts the gift of the pineapple which, absurdly, has simultaneously redeemed his belief in humanity and "cured" him of his rejection of earthly necessities. He moves - whether happily or miserably, unquestionably determined - off camera from the lower side, a blessed descension rather than an accursed ascension, to the sound of increasingly loud drums. In Buñuel's hometown of Calanda

it's a tradition to beat an enormous number of drums from noon on Good Friday until noon on Saturday in recognition of the shadows that covered the earth at the moment Christ died.**** At the end of Nazarin, Buñuel's "Jesus" is also dying, but it's a liberated spiritual death - one that, for the filmmaker, is just as representative and worthy of celebration as the death of Christ. To have endured years of such an overwhelming ritual of a town's religious

ties as Calanda's drum marathon, it's no wonder the director found it easy to sympathize with the different kind of religious awakening that his priest undergoes. After all, he was an atheist. Thank god.

~ MARCH 2011 ~

* There's actually a lot of hilarious moments in Nazarin: the people who enter and exit through Nazario's window rather than the door, Beatriz's amateurishly botched suicide, Andara's deranged decision to cover her tracks by burning Nazario's apartment (and putting the St Antonio figurine in with the kindling while "saving" the porcelain infant in its arms) are just a few examples. The part that makes me laugh the most is when Nazario's fellow priest believes that he wasn't up to any hanky panky with Andara while she was hiding in his apartment because she's "too hideous."

** For more on the historical Jesus, I recommend Paul Verhoeven's recent Jesus of Nazareth, an exegesis of research and interpretations of historical texts the filmmaker collected as a member of the Jesus Seminar. While it's probably not the best book you could read on the subject, going over the subject through Verhoeven's eyes is incredibly entertaining. He doesn't mention Buñuel's film in the book, but he admires Pasolini's The Gospel According to Saint Matthew.

*** I've read articles that call the sequence between Beatriz and her boyfriend a "flashback," but it's absolutely a fantasy. Brought on by a raucous fight between two prostitutes (during which Buñuel makes sure to include a shot of their exposed legs), Buñuel even goes out of his way to give her fantasy that "wavy dream" lens effect to distinguish it from the rest of the film, pretty significant considering the way dreams and reality bleed into each other uninterruptedly in most of his films (just compare it to scenes in Belle de jour which are abruptly revealed to be Severine's sexual fantasies.) In the scene, Beatriz bites her lover's lip causing it to bleed, dominating him in a way she could never do in real life. This sequence alone makes up the quota of Buñuel's signature explicit sexuality that the rest of the film is notably lacking.

**** On a side note, I got real excited when my 16 month old daughter started beating the table in rhythm with the drums while I was watching the end of the movie. "Good job, Odile - you understand the symbolism!"

I think this general misunderstanding of what Buñuel's about is partly to blame for Nazarin being such a tough sell to critics at the time (it might still be today) and its unexpected acceptance among parties who really should have felt the most scathed by it. Renata Adler's confused 1968 review for the New

York Times called the film "grim" and "relentlessly pessimistic." French newspapers thought the movie carried an evagelical message, political reviews declared it a flagship for anticlericalism, yet it was nearly awarded by the Catholic church(!) At the same time, the film was a huge hit: it won the international prize at Cannes and allowed Buñuel to return to Spain and make Viridiana, in a lot of ways a sister film to Nazarin

which nevertheless received much more one-sided contemptuous responses - although it was awarded the Palme d'Or, it was denounced by the Pope; Bosley Crowley called it "an ugly, depressing view of life" (was it just because the idea of a woman "rotten with piety" seemed more slanderous and perverse than what was seen as a parody of the life of Jesus?) Like Viridiana, the ineffective priest Don Nazario is a character acknowledged as having a "heart of gold" yet often described

in so many words as "a little nutty" in the same breath, his attempts to spread Christian goodness to the heathen masses of turn-of-the-century Mexico as misdirected as the former's attempt to rehabilitate a group of wretched street urchins to some form of Christ-endowed civility. Both films, each respectively based on a novel by Benito Perez Galdos, feature one spectular Buñuelian moment - Virdiana the corruption of the image of The Last Supper,

Nazarin a portrait of Jesus laughing mockingly at a wounded, hallucinating prostitute - but are on the whole much more grounded in reality than some of the director's other famous films, although he can't resist throwing in the voice of Nazario chanting "mea culpa" and a creepily adult-sounding boy being spanked outside to compliment the savior's smiling visage. The Jesus image is the only real example of surrealism in Nazarin, its humor is more harsh and less broad*,

its setting in the days of Porfirio Diaz's dictatorship arguably the closest Buñuel came to depicting life under Franco. Finally, although the film reflects the kind of cruelty that existed around the time of Diaz and his tyrannical "pan o palo" policies, that specific government doesn't play a part in the story, so like Viridiana it's not readily apparent exactly who the director's satirical target is.

I think this general misunderstanding of what Buñuel's about is partly to blame for Nazarin being such a tough sell to critics at the time (it might still be today) and its unexpected acceptance among parties who really should have felt the most scathed by it. Renata Adler's confused 1968 review for the New

York Times called the film "grim" and "relentlessly pessimistic." French newspapers thought the movie carried an evagelical message, political reviews declared it a flagship for anticlericalism, yet it was nearly awarded by the Catholic church(!) At the same time, the film was a huge hit: it won the international prize at Cannes and allowed Buñuel to return to Spain and make Viridiana, in a lot of ways a sister film to Nazarin

which nevertheless received much more one-sided contemptuous responses - although it was awarded the Palme d'Or, it was denounced by the Pope; Bosley Crowley called it "an ugly, depressing view of life" (was it just because the idea of a woman "rotten with piety" seemed more slanderous and perverse than what was seen as a parody of the life of Jesus?) Like Viridiana, the ineffective priest Don Nazario is a character acknowledged as having a "heart of gold" yet often described

in so many words as "a little nutty" in the same breath, his attempts to spread Christian goodness to the heathen masses of turn-of-the-century Mexico as misdirected as the former's attempt to rehabilitate a group of wretched street urchins to some form of Christ-endowed civility. Both films, each respectively based on a novel by Benito Perez Galdos, feature one spectular Buñuelian moment - Virdiana the corruption of the image of The Last Supper,

Nazarin a portrait of Jesus laughing mockingly at a wounded, hallucinating prostitute - but are on the whole much more grounded in reality than some of the director's other famous films, although he can't resist throwing in the voice of Nazario chanting "mea culpa" and a creepily adult-sounding boy being spanked outside to compliment the savior's smiling visage. The Jesus image is the only real example of surrealism in Nazarin, its humor is more harsh and less broad*,

its setting in the days of Porfirio Diaz's dictatorship arguably the closest Buñuel came to depicting life under Franco. Finally, although the film reflects the kind of cruelty that existed around the time of Diaz and his tyrannical "pan o palo" policies, that specific government doesn't play a part in the story, so like Viridiana it's not readily apparent exactly who the director's satirical target is.