VIDEO ODDITIES

by john cribbs

For those just tuning in: what I'm doing in this series is tracking down interesting movies I've never heard of based on the ancient art of the "video box." For younger readers a "video" was an analog system used to record sound and images onto a continuous stream of waves; a format which pre-dated dvd, Blu-Ray and HD streaming. You would take a trip to an establishment called a "video store" to rent these items from an actual person and return home with them - the video, not the person - to enjoy at your leisure (you had to bring 'em back, though.) I'm basing my selection on the outrageous boxes these "videos" came packaged in, the kind that helped us decide whether a movie looked like it was worth our time back in the days before the internet started telling us everything there was to know about every film before they've even been released. Then I'm writing about them - simple as that. With the inevitable extinction of the video store it's become more difficult to hunt down some of these more obscure titles...they're becoming harder to find than Bigfoot.

Video Oddities #12: SCREAM FOR HELP

What do you write in that diary all the time, Christie? The Life and Times of a Teenage Sex Maniac?

It's rare to come across a movie like Scream for Help, a film that is absolutely insane. That is to say, the film itself is a crazy person. I'm not accusing the director, the writer, the actors or any individual involved of being crazy - just the movie. And I don't mean that in the context of "Dude, this movie's fuckin' crazy," like the actual events depicted in the film are mind-blowingly unbelievable as if I were discussing The Road Warriors or Oldboy - I mean this movie seems like what a mentally unstable adult would be if he was a movie.

When I look back on past Video Oddities, there's always a palpable human presence behind the madness. Movies like Microwave Massacre and Big Foot make attempts at humor that ground the freakish proceedings. The Killing of Satan and Satan's Cheerleaders have awesomely cheap special effects to remind the audience that there was a supervised post-production process. Even when you're dealing with something as out there as My Brother Has Bad Dreams, which is certainly nuts, there's always a sense that the director's keeping an eye on things as if to reassure the audience that he's in full control of all this craziness. Not so with Scream for Help: it totally goes off the rails. I honestly don't think it would be exaggerating to claim that at some point during its running time, this film gains its own maniacal sentience and leaves everyone involved with it behind. It possesses itself.

It's actually great, though - best Video Oddity I've watched since Amsterdamned. Which isn't to say that it displays Amsterdamned's competent acting, confident storytelling, sparks of directorial ingenuity or above-average technical accomplishments. Actually if I'm comparing Scream for Help to a past Oddity it should be either The Dead Pit or Mongrel, since this marks the third time in the series where I've been familiar with the filmmaker's work. We at the 'smoke have always been fascinated by Michael Winner's career, and I consider myself a fan. I even named one of our recurring series, the character actor apprecition "I'll Never Forget Whatsisname," after one of his early films. But I'm certainly not an apologist: even for a workman director, Winner's filmography is all over the map. Thematically, the closest to auteurism he ever came was the six films he made with Charles Bronson between 1972 and 1985 (Chato's Land, The Mechanic, The Stone Killer, Death Wish 1-3), and even those films have done as much to damage his reputation as they have to bolster it. He definitely walks a fine line between class and crass, and while his work tends to topple over into the latter category more often than not it's hard to write him off entirely since he so often paradoxically wavers between the high and low brow. He would adapt a Gilbert & Sullivan musical into a movie, but sacreligiously have the music rewritten to resemble Cha-Cha. Or direct an updated version of classy noir The Big Sleep that moved the subtle pornography subplot of the novel to the foreground. His ode to Gainsborough costume melodramas of the 1940s is a raunchy leather-fetish sex-revenge romp that infamously features a pre-fame Counselor Troi getting her dress literally whipped off by Faye Dunaway. He'd do an Agatha Christie adaptation with a notable cast, yet have it co-produced by Golan & Globus (Winner's partners through most of the 80's) with all the production value the Cannon label indicates. Even Winner's face, with its tiny yet shining eyes, big kissable cheeks and omnipresent friendly smile, was marred by a constant bright orange tan job that lent it an unsettling ophidian texture.

As one of the UK's only non-social realist filmmakers of the 60's and 70's, Winner always seemed a kindred spirit with Ken Russell: the two directors shared an equal fascination with the elegant and vulgar. Yet the integrity of any one of their exorbitant films was always in danger of falling apart due to a careless smattering of bad taste (I guess Peter Greenaway would fall under the same category). Since his filmography is mostly made up of straight-up action films and broad comedies, Winner was always doubly susceptible to an overindulgence of tackiness. Although he was a popular personality across the pond, enjoying a successful post-film second life as witty epicurean restaurant critic, here in the U.S. he's often stuck with the reputation as the uncultivated (or "controversial," if the writer's being polite) director of the first three Death Wish movies. I don't want to spend too much time on Winner - I'm anxious to dig into this movie - but it's important to understand how Scream for Help falls squarely between Death Wish II and 3 both chronologically and spiritually, perfectly embodying the balance between gritty nastiness and goofy nonsense. DW II was already dipping its toes in the sea of silliness by having Laurence Fishburne's rude creep get shot through his boom box, but its graphic rape scene is testament to Winner still being able to elicit a reaction from the audience, for better or worse. But whatever arguments there are to be made in support of Part II being an extension of the original's moral ambiguity and social commentary don't come close to applying to Part 3, a giddy exercise in good ol' excess and unabashed puerility. I wasn't sure what to expect going into Scream for Help: I figured it couldn't possibly be as weird as Hannibal Brooks, in which Oliver Reed and an elephant are on the run from the Nazis, or Won Ton Ton: The Dog Who Saved Hollywood, Winner's first film coming off Death Wish (when he theoretically would have had his choice of follow-up project!) Would this be a sensitive portrait of a tormented young woman a'la 1977's The Sentinel (which even Ricky Butler says is one of his best films) or a borderline misogynistic one like his penultimate splatterfest Dirty Weekend (the only movie I've ever thought should open with a disclaimer advising the viewer to prepare for a long shower after the film was over)? As it turns out, the movie isn't quite outrageous enough to end with the bad guy being bazooka'd out the window, but make no mistake - he will be horribly killed by the hero, who's happy to end the film with a self-satisfied Kersey-esque quip.

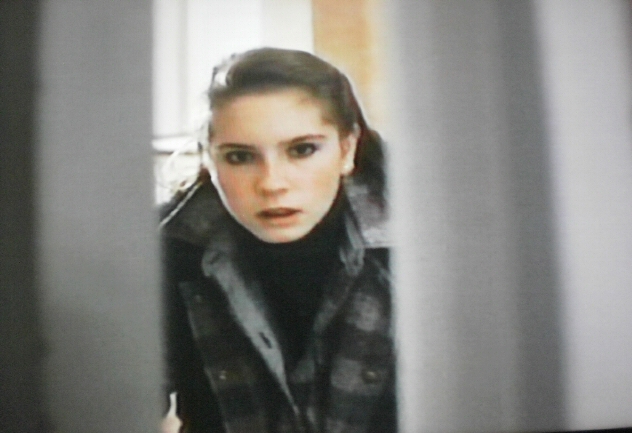

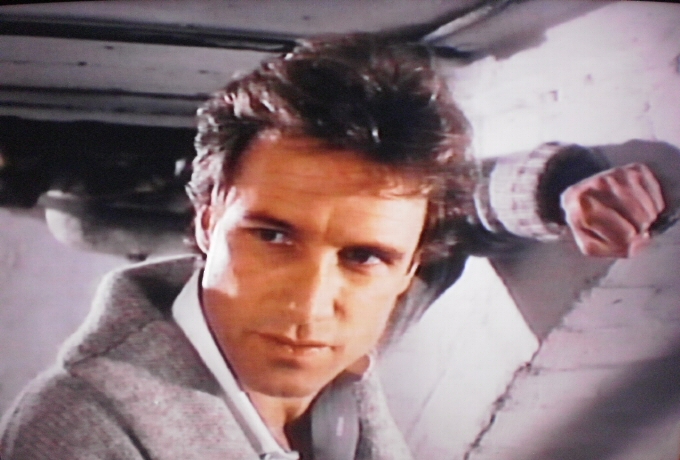

In voiceover, the lead character introduces herself as 17-year-old Christie Ruth Cromwell (full names are important in this movie) and bluntly states, "I think my stepfather is trying to murder my mother!" This of course immediately made me think of the Joseph Ruben-Donald Westlake-Terry O'Quinn classic The Stepfather, a movie Winner's film preceded by three years (and on which Death Wish author Brian Garfield received a "story" credit), but that comparison more or less ends with that line. Because while the plot - teenage girl's suspicions of homicidal intent written off by everyone as natural animosity towards stepparent - is similar to Ruben & Westlake's film, Winner keeps his story strictly within the narrow perspective of amateur sleuth Christie Cromwell. Christie, a Holly Marie Combs-looking, tiny-eyed, bottom-of-lip-biting gal, doesn't just become increasingly concerned over the possible danger to herself and her hapless mom a'la Jill Schoelen's stepdaughter; from the very beginning she obsesses over every movement of Paul Fox, the grinning car salesman who's won her mother's heart, convinced her to give Christie's dad his walking papers and ingratiated himself in their comfortable New Rochelle home. Paul Fox's conquest of her mother and extramarital activities with local leather pants aficionado Brenda Bohle just happen to have coincided with Christie's inauguration into womanhood, a vulnerable time for a virginal teen just trying to make heads or tails of this topsy turvy transition - she shouldn't have to deal with traumatic exterior events that further complicate her outlook on sex. So Scream for Help's straightforward story of snooping is really the sensitive tale of young girl's voyage towards sexual awakening, related in the sleaziest way imaginable.

Again, if you're familiar with the more puerile of Winner's oeuvre* (read: Dirty Weekend), this shouldn't come as a surprise. But 1) this is Video Oddities - we don't focus on the filmmakers, and 2) so slippery is Scream for Help's unique form of sleaze, it seems to somehow get away from its director and form a symbiotic bond with the film itself. And like Spider-Man's black costume, it corrupts absolutely. Just like a pubescent, ponytailed Jeffrey Beaumont, Christie finds that her investigation into Paul Fox turns her into a P.I. peeping tom: five times in the first forty minutes of the movie, she discovers couples in compromising positions. Three of these encounters are Christie stumbling onto Paul Fox trading fluids with co-conspirator Brenda Bohle (they catch her spying all three times - you'd think they'd be more discreet about hooking up after the first one!) The other two happen by chance when Christie tries to present evidence to her mom, who's busy getting her own taste of Paul Fox, and best friend Janey Ralston, preoccupied with high school sweetheart/Zack Gallagher doppelgänger Josh Dealey, so even those accidental encroachments are directly related to this older man who consumes Christie's mind. From her lingering outside the window of the cheap motel where Paul Fox has arranged his love nest, outside the bedroom down the hallway of which Paul Fox's name echoes from her ravished mother's lips, and outside Brenda Bohle's house where she's poised to snap a polaroid of Paul Fox reaming Bohle from behind, Christie is also clearly captivated by these sordid scenes she finds so repulsive. Each tryst, on top of being bawdily filmed acts of infidelity and underage hanky panky, either directly or indirectly furthers the conspiracy against Christie and her mother, yet because of her own budding state of sexual growth she can't help but feel some kind of confused libidinal affinity with them. When she sneaks an initial peek into the Bohle household with the intention of obtaining photographic evidence of Paul Fox's perversity, she's faced with her own reflection in the mirror. The day after pregnant Janey Ralston is horribly killed by one of the bad guys, Christie gives up her cherry to poor Janey's not-too-distraught boyfriend Josh Dealey. And, perhaps least subtlety, she hangs around in her bedroom wearing a shirt that says "muffs."**

The marvel of Scream for Help is that, taken at face value, there's nothing wrong with mature couples enjoying a consensual roll in the hay. But seen through the vestal eyes of an inexperienced Christie, each intimate act seems more twisted than naughty, more depraved than kinky, with Paul Fox cast as the ultimate sexual deviant. Of course it has something to do with all these sudden exposures to sex being related to Paul Fox's sinister murder plot, but Christie can't even make her best friend understand after catching her in flagrante aardvarkus and freaking out:

"It's because you're still a virgin, right? That's why you're so upset."

"I'm upset because my stepfather tried to murder my murder!"

Even if Christie didn't have an adorable poster of some shirtless bo-hunk on her bedroom wall with the caption "Looking Good," the method of her investigation alone singles her out as a naïve virgin in a valley of dirty-minded philanderers. How precious is this scenario: after becoming suspicious of how Paul Fox spends his afternoons after a long day on the car lot, she trails his car on her bike, pedaling her little heart out only to be thwarted when "he turned left and I lost him." Did she not anticipate that he would eventually turn? Is she so ignorant of road travel conduct that she assumed he'd cruise in a straight line at 10 MPH for about half a mile before reaching his destination? Unable to keep up with him, she spreads her tail over several days, just picking up at whatever corner where she lost him last time (and proudly detailing her method of pursuit after it finally pays off - see Hitchcock, this is how you make scenes of tailing someone interesting!) She's 17 and apparently rich, yet doesn't have a car or even her license - in fact, after she's dug up the first bit of dirt on Paul Fox he's able to buy her off with a new bike, encouraging her to continue turning her wheels so the disreputable adults can continue their dirty deeds.

When she does get behind the wheel of a car, Christie is further frustrated: Paul Fox has tampered with the engine (later a grease monkey sites a disconnected caw-bah-ratah spring, an apparently important car part that appears to control the gas, the brakes and the steering), resulting in a helter-skelter barrelling through town with a terrified Josh Dealey in the passenger's seat.*** The fact that Dealey is Christie's partner during her first disastrous turn behind the steering wheel as well as her first disastrous copulation should be lost on nobody, as well as the fact that Paul Fox is the one who messes up both of these very important events in Christie's life. Paul Fox is so dominant a presence in this crucial point of Christie's adolescence that everyone around her not only assumes her pubertal turmoil is the reason for all this "my stepdad's dangerous" hullabaloo, they base their behavior on it. In the middle of the film, after Janey's been murdered and evidence against Paul Fox seems to have moved far beyond the circumstantial, the police commissioner is still convinced Christie is simply muckraking a man who sexually intimidates her. This previously unthreatening character mocks her claims while swiveling back and forth in a leather chair, grinning playfully, his legs obscenely spread open, teasing her about being a "good little actress." The staging of the scene is genius: it's set in Christie's house, but it feels like it's taking place in the office of some amorous principal. The commissioner (who on top of everything is Josh Dealey's dad, so you'd think he'd take the horrible killing of his son's girlfriend a little more seriously) comes off as so unequivocally lecherous that if anybody entered the room in the middle of this, they'd want to know what the hell was going on. This kind of lewd bullying from such an unexpected source doesn't do much to alleviate Christie's insecurity, who's ready to join the convent. Despite Josh Dealey's reassurance that the next time they make love, it "won't be like it is in this picture," referring to the polaroid of sweaty schemers Paul Fox and Brenda Bohle knocking boots, Christie has already come to the conclusion: "Sex is just plain horrible!"

You can't blame Christie for being flustered: you've got one man electrocuted, one pregnant high school chum mowed down by a car, one automobile with the carborator spring tampered with, one mom tumbling down a giant flight of stairs like a Donkey Kong barrel. All these alleged accidents within days of each other, evidence linking Paul Fox to the site of Janey's murder, a strong motive for Paul Fox to want to kill his wife compiled with an affair with a younger woman - Christie's 17, she's not a kid, why aren't people taking her allegations seriously? At least in The Stepfather, Terry O'Quinn has no clear motivation: he's just crazy and nobody could predict that he was a monster. But an ambitious, handsome young cat like Paul Fox marrying a rich older woman with a giant house whose father (Paul Fox's former employer) owned "half the town?" To add insult to injury, literally seconds after Christie is informed that Janey has died at the hospital, Paul Fox tactlessly thanks her for not snitching on him!

He might as well have explicitly said, "Sorry I killed your friend and am planning to kill you, but thanks for not telling your mom about me banging the younger broad I plan to marry after murdering her in that hotel room." The audacity of Paul Fox is matched only by his malice, which turns playful once he's caught Christine in bed with Josh Dealey and chides her with the immortal line, "I'm not like you, Christie - I'm very forgiving of your sexual foibles."

This reminded me of Uncle Charlie hypocritically admonishing his niece and the young cop after catching them "in the garage" in Shadow of a Doubt: yes, we were hooking up - aren't you a multiple murderer? Like the relationship of Charlie and Uncle Charlie, there's something oddly conspiratorial about the antagonism between Christie and Paul Fox. In Shadow, an agreement is struck that the younger Charlie won't expose her uncle as the Merry Widow Murderer, a pact that - out of convenience - holds up even after he's been killed trying to murder her on a train at the end of the film. In Scream, even though Christie hates Paul Fox and does everything in her power to protect her mother from him, their shared knowledge of his evil scheme grants them an intimacy she never would have accepted if he'd just been a boring old non-homicidal stepfather: the plot to murder her mother breaks the ice in their relationship! When mom plummets down the steps of their house and appears to have been killed, Christie looks up at Paul Fox and shouts, "You did it, you finally did it!" instead of "Mom, are you ok?" I don't think it's a mistake, or bad delivery, that her reproachful line sounds more like encouragement: Christie has unintentionally brought herself into Paul Fox's evil ploy, and its instigator seems to mutually respect her for figuring everything out while her mother wallows in blissful ignorance. In this movie, general understanding is akin to sexual awareness, and the ones who are most knowledgeable of the secret plot are the most sexually depicted: scheming mastermind Brenda Bohle is shown fully nude, covering up the patrially nude Paul Fox (who's only partially in on the full scheme). Whereas Christie's mom, being the most oblivious to the developing machinations, is heard but not seen during her sex scene. Christie, in the course of slowly connecting the dots, loses her virginity - the two could not be less exclusive of each other. Paul Fox is so prevalent in Christie's passage to womanhood that he's even there to witness her postcoital freak-out when blood from her ruptured hymen (Michael Winner = class act) soils her white sheets. The liberation of making it through her "first time" is then instantly linked to further evidence of the external threat as Paul Fox stops Christie from running into the bathroom, an act that makes her understand he's booby trapped the gas-fired water heater inside it to explode.

* I'm going to start working on a spec script called The Puerile Oeuvre.

** It's not the band, they didn't form until 1991.

*** During this scene there's a long shot of the stuntwoman driver casually pushing hair out of her face while the car is supposedly going haywire.

<<Previous Page 1 2 Next Page>>

home about contact us featured writings years in review film productions

All rights reserved The Pink Smoke © 2014