THE SMOKE's 50 FAVORITE FILMS OF THE 90's

Yep - lists. The internet's overflowing with them. "8 Best Pie Flavors from Central America"...you get the idea. But a discussion of notable films from the 90's came up years ago among future 'smoke writers (back in what is now being referred to as "the myspace days"), and we wanted to bring that discussion back. All five participants - John Cribbs, Christopher Funderburg, Ian Loffill, Marcus Pinn and Stu Steimer - were asked to come up with their 75 favorite movies from that long-ago decade: the results were then calculated into one master list of 50. Each film will be written about over the next five weeks as we draw out this self-indulgent entry into the endless abyss of movie lists, classed up thanks to contributions from some of our favorite film writers.

<<<CLICK HERE FOR #'s 41 - 50>>>

<<<CLICK HERE FOR #'S 36 - 40>>>

<<<CLICK HERE FOR #'S 31 - 35>>>

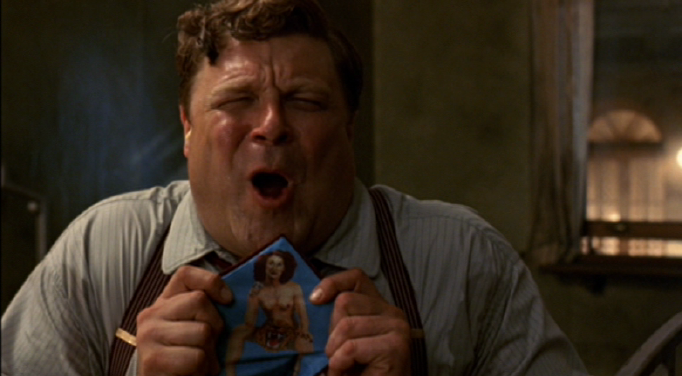

30. BOOGIE NIGHTS (1997, Paul Thomas Anderson)

stu steimer

Let me start off by saying that generally I don't really care about movies about making movies. That is not to say that there are not ones that I don't enjoy there are plenty of them, but half the time they end up coming off as bloated self-serving piles of horseshit (Contempt is the most appropriate title for a film I can think of because that is exactly what I hold for it.) So I guess it should be of some peculiarity how Boogie Nights is not only my favorite film of the 1990's, but would rank amongst my 30 favorite films ever. Of course an obvious explanation one would think would have something to do with its subject matter, as I do love pornography the hardcore stuff has gotten me through many years of lonely nights, and there are plenty of films to come out of the Boogie Nights period that I think are legitimately good films (actually, besides Bat Pussy, the best pornographic films are the surrealist-cum-absurd gems of filmmakers like Rinse Dream [specifically Night Dreams] and Gregory Dark produced in the early-mid 80s. The sex were typically the most uninvolving parts but this is getting off-topic.)

But nevermind my dateless hallucinatory lapses covered in puddles of my own dried sorrow, Boogie Nights is a solid film regardless of its subject matter (though it definitely does not hurt, the setting and the backstory of the pre-home video industry is certainly an interesting one) if this movie had been about the marketing team behind the creation of Spuds McKenzie I imagine that I would still be writing about it right now, my passion for it is as concentrated as the volume of sodium and carcinogenic additives the result of years of abusing Little Caesesar's Hot'n'Readys - pumping through my bloodstream.

Though its influences are rather obvious to anyone with a cursory knowledge of film from the 70's and onward (take some Nashville, add some Goodfellas, cut with barbiturates and Cialis) it still has this level of depth and style that I rarely see in mainstream films, especially ensemble pieces which seem to either go great or terrible. Even Altman would prove to never have much consistency with this later on in his career as evidenced by HealtH and Ready to Wear amongst about a half-dozen other misfires, both slight and major. Even Anderson's follow-up Magnolia, which I have grown to love enough to include on my own personal Top 75 films of the 90's list despite spending a good chunk of years in absolute loathing for it, carries the weight of flaws that the whole "everything is connected" ensemble subgenre is difficult to escape. Although Boogie Nights may spin a somewhat formulaic web spanning the rise, fall, and eventual salvation of most of its central characters amidst the sex and drug-fueled haze of the porn's golden age it does so with more sophistication and care than overt pretenses and forced manipulations would allow.

The characters may not all be deep or complex (John C. Reilly as Reed Rothchild is ostensibly watching the origins of Step Brothers or Walk Hard), but they don't necessarily need to be; the humor runs concurrent to the characters and story, as much of the film works as a satire as it does a drama; the humor is constant and self-effacing, the drama more deadpan than awkwardly forward which proves to be a much greater alternative than having the entire cast lip-sync to Aimee Mann.

Some of the players have obviously been inspired by and fleshed-out of real-life counterparts (Bob Chinn, John Holmes, Shauna Grant, and Veronica Hart being obvious examples) while others completely fictional. Although scenes from Autobiography of a Flea are re-created right down to the choppy edits and stammering of dialogue the film is hardly to be considered a biographical account of John Holmes, or anyone else for that matter. Pastiches and stories of the Los Angeles porn scene are spackled all throughout the film, some of which are very direct, the most notable being the Wonderland Murders which serves as a vehicle for probably one of the best sequences in the entire film, the intensity of Alfred Molina swaying in his bathrobe waving a pistol while the echo of firecrackers bounces off the walls is palpable, never waning even after a good dozen or so repeated viewings.

The tone, as previously indicated, is a melancholic one. Even the "happy ending," a montage sequence set to "God Only Knows" by the Beach Boys, where the camera fluidly tracks the characters, who by this point have all been battered in some way, emerging from the wreckage of the past still comes off more bittersweet than anything. The film ends here, with Dirk Diggler's donkey dick unraveling out of his pants like a never-ending roll of Bubble Tape, but the stories at least the stronger ones are hardly finalized: Amber Waves (Julianne Moore) still never regains custody of her child due largely in part to the world she has become part of, Jack Horner (Burt Reynolds) who fashions himself as an artist over pornographer ("I wanna suck them in with the story and the acting...I want to make the things that keeps them around even after they've come...") now dances on a crossroads between unemployment or accepting the inevitable shift of the industry which will eventually result in the distribution of films containing titles with phrases that will completely shift the English lexicon if it was difficult in 1980 for a porn director to overcome the elements and achieve even the crudest level of artistry with his work, imagine what it would be like when he has over 150 titles in the Chuggin' Grandma's Cumfart Cocktail series to compete with.

Anderson conceptualized this film, roughly, when he was 16, making it into the Dirk Diggler Story in 1988 before its final realization in 1997, and it shows. It is easily his best film (though Hard Eight could be close) and I have doubts that he will ever make a better one. Though the teaser for The Master does look pretty good.

29. BUFFALO 66 (1998, Vincent Gallo)

marcus pinn

Buffalo 66 is a classic example of that movie people love to hate, which makes perfect sense because the film's director, writer, producer, composer and star is someone people love to hate as well. Don't get me wrong, the movie has a very large and loyal following but at the same time I think this might be the most hated movie on the list next to Pulp Fiction. I know there are some of you out there who couldn't possibly fathom the idea of someone not liking a masterpiece like Buffalo 66 but trust me, they exist. And what's so unique about this movie is that even some of the people who claim to hate Buffalo 66 secretly love it but don't want to admit it because that means liking something that Vincent Gallo is responsible for. We all know his reputation - he wished cancer on Roger Ebert, has said every mean thing in the book about every celebrity you can think of and once maintained a website full of sexist, close-minded, right wing, contradicting, racist, self-loathing rants. He goes out of his way to support Republicans when he clearly isn't one himself and knows his average fan is the most NON-republican/conservative person in the world. Shit, he probably just cast Chloe Sevigny in The Brown Bunny so he could say that he got a blowjob on the big screen from Harmony Korine's ex-girlfriend. But you have to give credit where credit is due, and Buffalo 66 is a great movie.

Sometimes when a director tries to make a semi-autobiographical story about their childhood it turns out to be quite embarrassing. People are a lot more cynical and apathetic these days and no one cares about your personal problems or how you were raised (especially not enough to pay money and watch it on the big screen.) Even Gallo himself who has always been very open about his rough, abusive, dysfunctional upbringing isn't above poking fun at it as well. The basic premise is quietly silly and ridiculous: a recently released ex-con ("Billy Brown") is plotting to kill an old Buffalo Bills field goal kicker ("Scott Wood") who he claims ruined his life. Along the way he kidnaps a young woman (Christina Ricci, back when she was attractive) and forces her to pretend to be his wife to keep up appearances for his screwed-up parents (Ben Gazzara and Anjelica Houston.) Along the way, Billy and his Stockholm syndrome kidnap victim fall in love and he questions whether or not he wants to go through with killing Scott Wood after all. Buffalo 66 is a great blend of comedy and drama. Certain parts will have you laughing out loud (Billy's parents and the opening scene where he was to pee) while other moments will make you cringe (Patricia Arquette's cameo.) Some moments will leave you mesmerized (Christina Ricci tap dancing in the bowling alley) and other parts will break your heart (the breakdown scene in the bathroom.) It's clear that Gallo is a biter guy, but he isn't so bitter and self-loathing that he doesn't leave us with a sweet ending. Buffalo 66 has this unique grainy yet bright and colorful look, almost like we're watching old Polaroid pictures that someone dug up from an attic that came to life. The specific type of film that Gallo uses gives the movie a timeless look, as if the story could have taken place in either 1978 or 1998. And along with a fine cast of actors ranging from Ben Gazzara and Anjelica Houston to Kevin Corrigan and 90's "it girl" Christina Ricci, the film also serves as a little reminder that not only is an unrecognizable Mickey Rourke still alive, but so is Jan "Airwolf" Michael Vincent. Whether Gallo wants to admit this or not, Buffalo 66 has elements of early Gus Van Sant (specifically Mala Noche and Drugstore Cowboy), Jarmusch's Stranger Than Paradise with a touch of Two Lane Blacktop.

By the late 1990's Vincent Gallo wasn't the most well known name but he still managed to make little marks in pop culture here and there. Between the early 1980's through the mid 1990's Gallo formed a short-lived band with renowned artist Jean Michel Basquiat, made an appearance on the cult hip-hop TV show Graffiti Rock as one of the background dancers, was up for serious consideration to co-star in Reservoir Dogs as Mr. Pink, became one of Claire Denis' regular actors (Keep It For Yourself, U.S. Go Home and Nenette & Boni) and co-starred alongside everyone from Johnny Depp to Steve Buschemi. But Buffalo 66 put Gallo on a much bigger platform and he (and the film) gained a cult status that's just as strong now as it was back in 1998. It also got Gallo just as many fans (old school hipsters and Japanese people) as it did enemies. Before the film was done shooting, he made enemies with a good chunk of the supporting cast (specifically Ricci and Houston) and apparently when it played at Sundance, Paul Schrader made a big stink and walked out 30 minutes into the movie, which prompted Gallo to refer to him as a "half a man who wrote a couple of screenplays for Martin Scorsese." Buffalo 66 has become the one thing that everyone draws comparison to when Gallo directs or even acts in something that he didn't even direct. I always find myself cautioning people that when they're about to watch something that has Vincent Gallo in it that it's nothing like Buffalo 66 and if that's what you're expecting you're going to be disappointed. I know it's not cool to be remembered for just one thing, but there's still something to be said for that.

28. BARTON FINK (1991, The Coen Brothers)

stu steimer

Writing is usually hell. Not every writer is an introverted Poe or an alienated Kafka, digging literary trenches sinking further into the banks of isolation and societal withdrawal (not to say their work is quite as reflective of their lives as sometimes [over]stated both Poe and Kafka had a much more striking command for wit and humor than their reputations lead on, but this is for another discussion.) If you look through the annals of the literary world you're likely to find as many Hemingways, Woolfs, W. Somerset Maughams and Norman Mailers - writers whose lives were as dense and prolific as their output. Some spies, some soldiers, some socialites, some general adventurers, some most amalgamations of all categories. But the process of writing and I say this doing my best not to sound like the eponymous protagonist of Barton Fink but am going to end up directly quoting him anyways is always one of pain. Barton talks about the emotional pain that comes with drudging through man's despair to aptly articulate his vexation into the appropriate words, a mouthpiece for the common man; I'm just talking about laziness and lack of willpower generally I'd rather just be at McDonald's where it is safe and I have access to free WiFi to waste my remaining days of youth on YouTube watching obsessing over SkoalRebel's scathing commentary on the world as he sees it. Even now, writing this, I am in pain less of an intellectual strain and more of what I believe to be some mild form of food poisoning (though if it were not for this physical malaise keeping me alone indoors on a Saturday night I probably would have never even gotten around to starting this article, so it's working as my beneficiary here blood-shits, cold-sweats, hallucinations and all.) Nevertheless I have learned to never trust an artist, a writer, a musician, etc. who has clearly had fun with their material and generated it as a result of little-to-no obstacles of doubts followed by revisions followed by further doubts and this doesn't mean you can't be a narcissist, to be creative in any way practically demands a heavy ego from its creator. But you can tell who had fun, crafting it spontaneously without any semblance of care or thought without a roomful of previous creative abandonment trailing behind them you can tell because it is usually shit. "I find writing to be pure bliss," Barton's Faulknerian hero W.P. Mayhew comments in one scene later he is revealed to be a charlatan. There are times however when you come across the select few that actually possess that skill to create so effortlessly, punching away at the keys day and night, and do so with very real pronounced talent, a talent that is absolutely undeniable. Those are the ones that I who will sit in front of a blank word document for weeks hate most of all.

But to look at it as a whole: the crippling tedium, the faint sparks of ingenuity that make themselves known so rarely behind that blackening fog of nothingness only to immediately cease as the writer's train of thought shifts from the page to the surroundings where the familiarity bleeds away to an environment that becomes all the more alienating, you wonder if the thermostat that read 76 degrees is broken because the space feels stifling. Were the walls that close to me an hour ago? Did they move? The walls Jesus, what went into the mind of the person that painted this room? Who consciously vetted for the "barf and pee" look?

You find these distractions, no matter how trivial, and you zone in on them pretending to be annoyed but actually secretly pretty grateful that something has risen to bring you back into reality, away from the cold, dead glare of the monitor that has long ago shifted into a colorful screensaver. My distraction, at least as the present moment, consists of me pacing back and forth from my chair to the refrigerator, wondering if I should throw those carrots out. (Something is growing on them, and I think it is what has made me so sick, but perhaps it is just a fluke, and perhaps I will be fine if I were to eat them in the future maybe by then I will have built up a tolerance to the mold, or the fungi, or the bacteria, or whatever the hell that gray shit is.)

Barton's distraction comes in the form of a neighbor, Charlie, a heavy and boisterous but strangely humbling man of about 40 or so who shows up seconds after Barton calls the front desk to complain about his penetrating laughter from the next room over. He claims to be an insurance salesman the common man, as Barton refers, the kind that he writes about the kind that a career spent in the theater has brought him here, to write studio films pulpy wrestling pictures. But Barton's alleged interest in the "common man" is marginalized, his fascination and knowledge existing only within the confines of his own head. Charlie is very open and cordial, but every time he opens his mouth he is met with only the faintest acknowledgements, Barton transparently humoring him between a series of interruptions, proclamations of his supposed empathy for the everyman, launching into haphazard diatribes about the indescribable pain and burden of being that voice of so many. Barton's view and understanding of the world in which he so brazenly declares his own is as limited as that 150 square foot hotel room. To paraphrase an actual line from the film, Barton is simply just a tourist with a typewriter.

The hotel becomes somewhat of a hell for Barton figuratively and literally. He's got writer's block that seems to never be met with diminishment how can one, an artist with so much knowledge and understanding sink to writing a B-Movie? Nothing beyond a few words get written, the heat in the room is in a constant state of percolation, increasing with each visit from Charlie. Hours are wasted away staring at the wall paper, sickly peeling off the walls and shedding like snakeskin, the glue oozing like an infected pustule. And the frustration only increases: a woman's blood soaks through the bed sheets, Charlie skipping town just as the fuzz arrive. But on the bright side, the fever breaks and Barton completes the script in a matter of intense sleepless hours the best thing he's ever written, dense with real honest lyricism and allegory the exact opposite of what a studio producing wrestling pictures in the early 1940's wants. If the hotel is Bartons hell, then the studio system is surely his purgatory. Barton is told he is a hack, just another self-important writer floating in a sea of opportunistic smugness. Nothing he writes will ever be produced, but due to Faustian contractual obligations he is now stuck in the studio system.

Barton Fink came at a time when the Coen Brothers were still consistently making great films, long before the hit-or-miss 2000's (though A Serious Man and No Country for Old Men I would rank amongst their best, while just about everything else they have produced in the last ten years has left me yearning for even a lesser work from the 80's and 90's), but Fink remains the film in the Coens catalogue that I would place above everything else that they have done, and probably will do. It's dark and eerie in all the right places, claustrophobic, the Eraserhead influence apparent without feeling like a third-rate Lynch wannabe (something that is rare with most films inspired by Lynch's work), venturing down that trajectory of the surreal and metaphorical while leaving the pomposity behind. The film's wit and charm is subtle and underplayed a thankful contrast to the loud obnoxious bombast of The Ladykillers. Scenes are played straight, with the humor developing in natural deadpan spurts of alleviated tension simply everything I love about the Coen Brothers and nothing I hate, solidified in a runtime of under two hours. The last frame and Mundt's "tourist with a typewriter" speech are two of those cinematic moments that are probably going to stick with me forever.

27. HEAT (1995, Michael Mann)

ian loffill

After seeing Once Upon a Time in the West, Wim Wenders described it as "the limit...a killer." For him it was almost too much for one movie. It was the western to end them all, the summation of the entire genre. After a film like that, surely the western could go no further? I have to admit that although there are good things in it, I've never really cared for Sergio Leone's 1968 film (I much prefer his earlier Man With No Name trilogy) but I can certainly see what Wenders meant in his assessment. I share a similar view regarding crime movies and Heat. Certainly for me no crime movie since has come close to matching Michael Mann's extraordinary achievement. Subsequent films such as The Departed, American Gangster and Mann's own underrated Public Enemies attempted a similar feat - putting two A-list stars on opposite sides of the law in a cat and mouse game within a broader, multilayered crime story - but it remains unsurpassed. I feel that in modern terms at least, crime movies have superseded the place of the western in American cinema. Like westerns, they allow room for exploring a certain mythology, masculine values and a nation's history and outlaw stories. Writer/director Mann, who counts John Ford's My Darling Clementine amongst his favourite films, takes the moral framework of westerns and does his own modern morality plays.

I once heard it said that it takes about 25 years of maturing, hindsight and reflection for a film to become a true classic but in the case of Heat, which I first saw on video in 1996, I'd made a claim for it very early on and I still stand by it. Here the timing was near perfect, as this was towards the end of the era when both Al Pacino and Robert De Niro had any notion of quality control over their work. Just over a decade later, the two teamed up again in Righteous Kill to a derisory reaction. Here Pacino was in the middle of a major comeback that had begun with Sea of Love in 1989 and continued throughout the following decade with an Academy Award win (for Scent of a Woman - not exactly his finest moment, I know), a triumphant directorial debut (Looking for Richard) and some rather good movies along the way like Glengarry Glen Ross, Carlito's Way, Donnie Brasco and The Insider. De Niro meanwhile was still open to more offbeat material like Mad Dog and Glory, Jackie Brown, Wag the Dog and Cop Land. Alongside the same year's Casino, Heat has what I think is the most subdued and interesting performances that De Niro has ever given. This was shortly before he became the notorious sleepwalking paycheck player and connoisseur of bad comedies that we have grown accustomed to. It is also much different from the more showy "intense method actor" style that people tend to like and which bought him great acclaim in his earlier career in the seventies and eighties.

For some, this was a film that could never live up to its billing. A good point of comparison here is the 1981 film Death Hunt, which sees Lee Marvin and a vengeful posse hunting down fugitive Charles Bronson in the snowy North American wilderness. I enjoy the movie and the two stars are on good form but it's not as great as it could have been and journeyman director Peter Hunt probably wasn't up to the task in the first place. Incidentally it has a similar scene to Heat where the two stars come face to face and yet we only see them in separate shots. Needless to say, the two stars in that film dwarfed much of the rest of the cast. Michael Mann however wisely chose to surround his stars with a formidable line-up of players including Tom Noonan, Wes Studi, Mykelti Williamson, Jon Voight, Tom Sizemore, Natalie Portman, Diane Venora, Ashley Judd, William Fichtner and Danny Trejo, all of whom compliment the leads magnificently and even get them to raise their game. Particularly astounding is how supporting actors like Dennis Haysbert and Ted Levine make their roles count so much more than you would expect. Of all the cast members, for me it is Val Kilmer that is the most underrated asset of the movie. Chris Shiherlis is the film's most crucial secondary role, having a highly compelling story arc of his own. Although overlooked by many at the time, he deservedly got third billing on the film's poster and advertising. A stroke of luck and schedule changes allowed him to replace Keanu Reeves in the role at the last minute. I still wish that Kilmer, rather than Russell Crowe, had got to play Jeffery Wigand in Mann's next feature The Insider.

The contrast and common ground between the two stars is certainly electrifying: it gives the film its charge, but the overall tapestry is something else entirely. This is a true epic and the whole film is a wonderful balancing act that shows us both sides of the law. We see the hunter against the hunted, extrovert Vincent Hanna (Pacino) versus introvert Neil McCauley (De Niro). Both are devoted to their profession and have a survival instinct which leaves them unable to sustain anything meaningful in their private life as a result. McCauley is planning a new life abroad and as an ex-convict will do anything to avoid returning to prison. Hanna struggles through his messy personal life - he's now on his third chaotic marriage - knowing deep down that his work will always take precedence. Moral judgements and how these men choose to live their lives play a part in the outcome as well. The infamous ending was a gamble that richly paid off. Had the balance between the two leads not been so well thought out and played out it might not have worked. I often get frustrated when I get the impression that the makers don't quite know how to finish a film. However this is the kind of ending where it genuinely feels like the whole film has been building up to that very moment and I really can't think of a more perfect climax or imagine how any audience member could feel cheated. Mann is something of a perfectionist and he probably put more in to this than any other of his films; this was a long gestating project that he had been planning since the seventies, even having a dry run with a condensed version of the same story in his 1989 TV movie L.A. Takedown.* Compare the different endings of the two and you can see how horribly wrong and anticlimactic it could have been.

No matter how many times I watch Heat, I get drawn in to its multiple characters and episodes and notice things that I hadn't spotted previously. The film admires professionalism but it is equally interested in showing the very real flaws behind the people involved. In Chris' marriage for instance his gambling addiction is taking its toll. His long suffering wife is somehow strong, loyal and patient but also duplicitous. Some of the characters are spontaneous, adaptable and occasionally reckless, while others are strict professionals who have a rigid code. Mann returned to these differing ideals in Collateral. In a film full of great moments, the two that really make the film for me are relatively quiet make-or-break moments that get me every time. The first occurs before the daring bank robbery. We have already seen newly released ex-prisoner Donald Breedan (Dennis Haysbert) try to adjust to civil life in his job as a short order cook with a boss from Hell. When circumstances force McCauley to get a new getaway driver, he asks Breedan to do the job and it's agonising each time watching him come to that fateful decision. Later in the movie, McCauley gets impulsive for the first time and deviates from his plan by deciding to finish off Waingro, a former associate who double-crossed him. It's his one reckless moment in the film and it costs him. In many ways, Chris takes the route that McCauley should have taken.

It's easy to pick flaws in this film - unlikely plot turns, too many coincidences, the sense that Mann is perhaps a little bit more interested in the criminal side of the story, Pacino is given too many problems to deal with and runs away with the role in the process, etc. - and yet I don't think I'd change a thing about Heat.** It's tempting to see the film as too dense, overreaching and fatalistic, but Heat is so complex in its structure and dazzlingly assured in execution that it seems like everything happens here for a very good reason. It's almost as though fate itself was smiling on Mann when Heat came to fruition. I love all of his films to a varying degree, but I feel that this is the one above all others on which his legacy should rest. Besides his brilliant debut Thief, I dont feel like any of the others fell into place quite as perfectly as this one did. Heat was really the moment his career was building up to. It sets a standard that subsequent crime movies, much of nineties cinema, the two main stars and perhaps even Michael Mann himself could not possibly live up to.

* Much like his 1983 sophomore effort The Keep, Mann has disowned L.A. Takedown, but it remains full of interest for fans of Heat if only as a warm-up for the real deal.

** The same can't be said for Michael Mann, who is famous for tinkering with his films after release, with subtle adjustments often being made for each subsequent home video version.

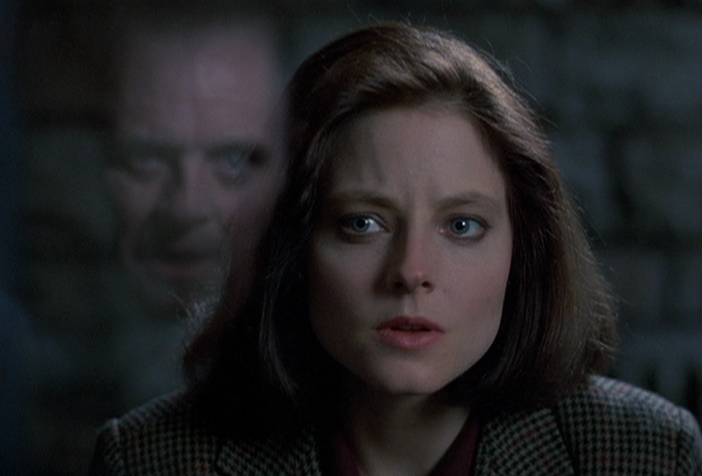

26. THE SILENCE OF THE LAMBS (1991, Jonathan Demme)

marcus pinn

Remember the sudden surge of interest in serial killers that started in the 90's and carried over into the early part of the last decade? A lot of that started with Jonathan Demme's The Silence Of The Lambs and its references to real-life serial killers like Ed Gein and Edmund Kemper. Whenever I find myself spouting out a random fun fact or piece of trivia about a serial killer, I quickly check myself and go: "Why do I know that?" Then I realize that, had it not been for Silence Of The Lambs and the internet, I wouldn't know most of the stuff I know about serial killers. True, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre was the first major film to base an iconic villain off an amalgam of real-life serial killers, but in my opinion Silence Of The Lambs is what really sparked the worlds interest in the subject. I realize the 80's brought us stuff like Maniac and Henry: Portrait Of A Serial Killer, but in my opinion those movies served no purpose but to sensationalize serial killers and almost turn them into antiheroes. Since Silence of The Lambs' 1991 release we've seen everything from serial killer trading cards to an entire subgenre of direct-to-video biopics on people like Gacy, Bundy and Dahmer (played by Jeremy Renner in an underrated performance.) I would even go so far as to say that the forensics aspect of Silence Of The Lambs influenced all those CSI/SVU/NCIS shows everyone watches today. Jonathan Demme actually made the FBI look cool, not just boring white guys in matching black suits. Unlike serial killing antiheroes Mikey and Mallory from Natural Born Killers or even Bonnie and Clyde to a certain extent, Jonathan Demme didn't try to glorify or make the villains in Silence Of The Lambs "cool." He actually made them downright frightening and instilled fear in us without using ghosts or hideous monsters. Because of scenes like Buffalo Bill's abduction of Catherine Martin, Hannibal Lector's escape or the first time we see inside Buffalo Bill's dungeon, Silence Of The Lambs could be considered a horror film just as much as it's considered a drama or a psychological thriller.

It goes without saying that Hannibal Lecter (a role first played by Brian Cox in Michael Mann's Manhunter) is the poster child for the movie and it's one of the greatest performances Anthony Hopkins have ever given. But what most people don't seem to realize is that in the two-plus hour film Hopkins has very minimal screen time. He's built up so much because his reputation and the horrible shit he's done is talked about so much before we even see him (biting off a nurse's nose and assaulting a guard.) Before we witness his violent side, Demme shows his manipulative side and how he uses his mind to mess with people. The way Demme shows Lecter's ability to get inside the mind of Clarice Starling and screw with her is pretty intriguing. We only see Hannibal's horrific side at the end of the film when he cuts off a police officer's face and wears it as a disguise. People get so caught up in the Lecter character that they forget Silence Of The Lambs produced another iconic villain in the form of Buffalo Bill, played by the great Ted Levine. True, the Buffalo Bill character is recognized in most circles as a great villain and he's been parodied and referenced in plenty of films and on television, but Anthony Hopkins' Academy Award-winning performance as Lecter kind of overshadowed Ted Levine's brilliant performance, which was worthy of just as much praise and acclaim as Hopkins got. The shot of Levine holding his dog while lowering the basket of lotion down to his kidnap victim is just as memorable as Hopkins' polarizing glare. It goes without saying that Levine is one of the greatest character actors to ever live, but Buffalo Bill went a little beyond Levine's usual portrayal of the mumblely, menacing bad guy or sidekick. Jame Gumb a.k.a. Buffalo Bill, a combination of Ted Bundy, Ed Gein and Norman Bates, is complex, scary and downright fucked up. Not that I sympathize or feel Bill's pain, but when Levine delivers the line "YOU DONT KNOW WHAT PAIN IS!" you feel it in your gut. His mannerisms are slightly off and original, reminiscent of no other tortured serial killer we'd seen in a movie before. When he mocks Catherine's scream for help you laugh and cringe at the same time. And his showdown with Clarice at the end really does have you on the edge of your seat. Buffalo Bill's introduction is similar to Lecter's in that the hype of his crimes are talked about so much that we already feel his presence in the movie long before we actually see him for the first time.

Naturally Jodie Foster's lead performance as Clarice Starling is a major draw as well. It's obvious she represents that underdog people love to root for - a tiny woman among a sea of big, intimidating men trying to become an FBI agent. What I love about the Starling character and how it's portrayed is that although Demme makes the gender thing obvious in a few key moments like the autopsy scene or the few times people hit on her on in the film, he still doesn't shove it down our throats and make us feel pity for some helpless woman. We don't get any forced "girl power" bullshit and Clarice isn't some unrealistic, tough as nails, man-hating cyborg-like cunt. She's smart and tenacious; we also see her weak and vulnerable side. During the training montages we see her succeed and fail. When she's in Lecter's presence she's just as scared and on the verge of tears as she is curious and focused on her task (getting insight from Lecter to try and catch Buffalo Bill.) Naturally she's a character women will automatically root for because we don't see many good female leads in noir/psychological thrillers, but she's just as intriguing to men as well.

TO BE CONTINUED NEXT WEEK WITH #'s 21-25

RELATED ARTICLES

home about contact us featured writings years in review film productions

All rights reserved The Pink Smoke © 2012