THE SMOKE's 50 FAVORITE FILMS OF THE 90's

Yep - lists. The internet's overflowing with them. "8 Best Pie Flavors from Central America"...you get the idea. But a discussion of notable films from the 90's came up years ago among future 'smoke writers (back in what is now being referred to as "the myspace days"), and we wanted to bring that discussion back. All five participants - John Cribbs, Christopher Funderburg, Ian Loffill, Marcus Pinn and Stu Steimer - were asked to come up with their 75 favorite movies from that long-ago decade: the results were then calculated into one master list of 50. Each film will be written about over the next five weeks as we draw out this self-indulgent entry into the endless abyss of movie lists, classed up thanks to contributions from some of our favorite film writers.

<<<CLICK HERE FOR #'s 41 - 50>>>

<<<CLICK HERE FOR #'S 36 - 40>>>

35. AUDITION (1999 - sort of, Takashi Miike)

ian loffill

Audition is a controversial choice for this list, not due to its actual content but because it has actually featured on many lists of best films of the 2000's. It only qualifies here through a technicality. According to imdb.com - the source I go to for a film's year of origin - it was shown at the Vancouver International Film Festival in October 1999, but it would reach much of the rest of the world the following decade. It's quite fitting that it exists on this borderline in that it signalled an end to a truly dismal decade for horror films and hinted at the direction things were heading in the new century, with several vivid titles from the Far East leading the way. Alongside Hideo Nakata's Ringu it was one of the films that helped attract the attention of audiences from the West towards extreme titles from East Asia and, for a while at least, it was an exciting flourish and a new direction for genre films. Actually it's debatable if this can be classed as a horror film. Like other films that transcend the genre (Tetsuo, Videodrome or Eraserhead for example) it almost defies categorisation and remains one of those unclassifiable one-of-a-kind movies. However, like most great shockers, the extreme elements that gave it its undeniable impact would become cliché in years to come. Largely it was imitated by filmmakers who completely failed to understand what had made it so effective in the first place.

Dream logic often comes into discussion of movies, but Audition has the quality of a harrowing nightmare. Even people who like this film have a hard time with it. It's certainly a film of famous "moments" (the mysterious sack in the apartment, the wire saw, the "pain doesn’t lie" climax etc.) but that's really selling it short. The nightmarish scenario stems from a romantic relationship that becomes more mysterious and sinister and that perhaps is where the film's strength really lies.

It starts as a kind of middle aged male fantasy where Shigeharu Aoyama, a widowed father, is encouraged by his son to remarry. Being busy, self-employed and very particular about who he would like to meet, a friend in TV and film arranges an audition for a female role that matches his specifications in a film unlikely to get financed. With almost a thousand applicants to sort through he chooses Yamazaki Asami, seemingly the woman of his dreams, and starts to court her. Everything seems to be going well until they take a coastal holiday, where he plans to make a wedding proposal, and events take a disturbing turn. The story shifts dramatically at this point but it's very carefully built-up to and throws the film in to increasingly dark territory where, like David Lynch's Lost Highway, it almost takes on a whole new identity. I'm sure some viewers were disappointed that it isn't really the gorefest that they'd expected but this is a film that, like the enigmatic Asami, plays brilliantly with expectations. After a fairly conventional opening 45 minutes the film becomes an elaborate puzzle game, forcing us to re-evaluate everything we have seen. There are telling signs that something is not quite right early on and certain lines pre-figures later events. Aoyama ignores the warnings of both his son and closest friend about the new love of his life and is drawn to Yamazaki Asami (who admits she is a clingy sort of woman) through a rather morbid passage about herself in her actress resume: "To live means to approach death gradually. I have learned that by my own experience."

Takashi Miike's films are certainly an acquired taste, but Audition is usually the one I mention in order to challenge his doubters. He has made a staggering number of films and inevitably some can feel rushed or unfocused. Of the ones that I've seen Audition, with its thoughtful and relaxed pace, seems the most elegant, confident and well-realised. He was of course aided immeasurably by a smart screenplay by Daisuke Tengan that added a highly enigmatic aura that was less evident in Ryu Murakami's more linear and self-contained novel. False trails abound in a Hitchcock manner, by giving characters, objects and entire scenes an emphasis that misleads viewers. The central relationship is quite affecting before the story shakes it to its horrific core. Even the clues to Asami's past - the record company producer she claims to know, the derelict ballet school she once attended, the closed bar she supposedly worked at – start to resemble a grim fantasy. It all plays out like a realisation of some of the worst fears that people have about relationships: a person becoming too needy, possessive partners, breakdowns of communication and trust and the worrying possibility that you don’t know that person’s true self. The film is a good contender for the world’s least appropriate date movie but if nothing else, commitment-phobes may feel vindicated by this. Exploring gender roles, alienation, sexual anxiety and generational and cultural values it’s a genuinely challenging film that can be read in many ways. There is much to discover in this truly modern film, one that still surprises and for all its confounding detail gets more fascinating and rewarding on further viewing.

34. THE MATCH FACTORY GIRL (1990, Aki Kaurismaki)

ian loffill

I did try to avoid having too many features by the same director on my list of favourite films of the 1990's, but Aki Kaurismaki proved to be a filmmaker I found impossible to reduce to just one or two choices. I'd certainly count him among my 5 favourite filmmakers and The Match Factory Girl still ranks as one of his finest efforts. If there were any concerns at this point in his career that the Finnish auteur had softened his approach following the success of the light-hearted Leningrad Cowboys Go America, or was eyeing the mainstream by making a feature in Britain (I Hired a Contract Killer), Match Factory Girl should have put those worries to rest. It's possibly his darkest film; the conclusion of his 'Proletariat Trilogy,' following Shadows in Paradise and Ariel, the latter of which he claimed was a "documentation of the destruction of Finland" and is just about as unsentimental as a film gets. Perhaps recognising that he couldn't go any further down this route without descending into outright miserablism, subsequent efforts have shown more traces of hope. The deadpan humour that many associate with him is subdued here. You could see it as a melodrama or a morbid comedy but it's perhaps too black and bitter to be either of those things. Here we see a fragile woman facing and finally striking back at an uncaring and harsh world. In the wrong hands the story would seem too cruel, simplistic or even incomplete but here it is the honesty and directness of its telling that is truly startling. I can't help warming to a film that concentrates on loners and defies a society that ignores or abuses them.

This is the director's most intense character study and a lot of the credit for this film should go to his frequent female lead Kati Outinen in the title role. Her melancholy face perfectly personifies the wounded pride and quiet anger slowly festering inside. Gradually we come to realise the void in Iris' life, first through its routine in her job and home life then through the rejection she faces. The film shares her small pleasures – diners, plants, cinema trips (she even cries during a Marx Brothers movie), reading, listening to the radio and buying a dress. These are all acts that, like her eventual revenge, seem like ways of transcending her frustrating and marginalised existence. Kaurismaki is unlikely to find another performer who embodies his caring but bleak worldview as well as Outinen. Besides the late Matti Pellonpää the only one who I think has come close is Maria Heiskanen. She fit so perfectly into the director's gallery of players in Lights in the Dusk that it seems a shame they have only made one film together so far.

At the end of the 1990's Kaurismaki would get to make a silent film (Juha) but he had already come pretty close to achieving that goal at the start of the decade with Match Factory Girl. Here his minimalist style was taken to its furthest point to date and it helped him find a more mature expression in the process. Kaurismaki is a master of nuance and every line, detail and gesture is carefully presented. Anyone who has seen or read an interview with the man knows that he doesn't care much for small talk. The first line spoken by a character occurs almost 15 minutes into the film. News reports and songs on the soundtrack do most of the talking. Not a single word or scene is wasted here, possibly because as well as directing he wrote, produced and edited the film and he surely knows a thing or two about economy. Understanding the virtues of brevity, the film is just over an hour long. This was part of an early campaign that the director had to challenge conventional wisdom about the length of feature films. Eventually he yielded or possibly had a change of heart. His more recent features have been longer, though not necessarily better. Interestingly, he seems happy to continue making the occasional short segment for European anthology films (Ten Minutes Older: The Trumpet, Visions of Europe, To Each His Own Cinema and the forthcoming 60 Seconds of Solitude in Year Zero.) Perhaps he does them in order to help maintain the formal discipline of his earlier work. His filmmaking signature was already well established by this stage; he's modified it only very slightly in subsequent features, but if only for its blunt and unforgiving tone Match Factory Girl has a unique and very special place in his output.

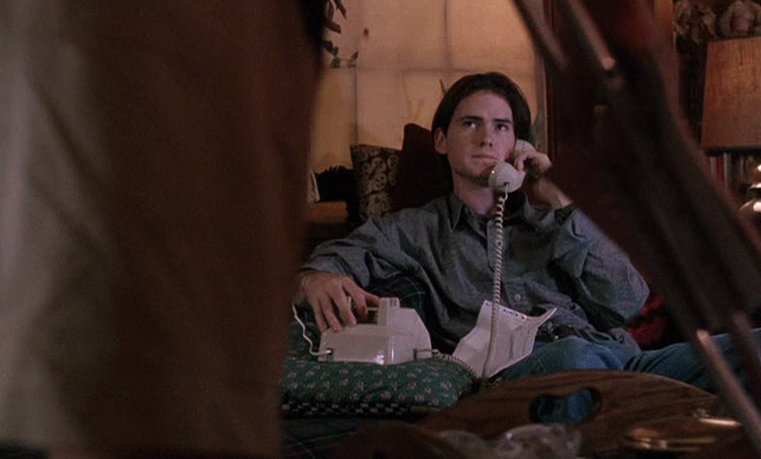

33. SPANKING THE MONKEY (1994, David O. Russell)

john cribbs

"I think I'm under environmental distress, how about you?" The question is almost inviting. If anything, the incongruously waggish tone of David O. Russell's darkly comedic debut suggests that we all need a little environmental distress every so often, that it can be as cleansing as it is traumatic. For college student Ray Aibelli, who spends his summer vacation glowering resentfully as he tends to his wounded mother at the behest of his bullying father, the claustrophobic suburbs are like a giant, embryonic cocoon with immaculately maintained front lawns. Ray unwittingly withdraws into the shell of his parents' tranquil home as if tethered to the sofa, venturing out only to walk his absent dad's dog or sulk in the company of some high school buddies, blaming his confinement on outside influences despite his own reluctance to flee. Rather than report to a prestigous pre-med internship, he's playing nurse to his dubiously incapacitated mother, allowing himself to be intectually undermined and humiliated into humble prostration. One line after another gets crossed as he carries her to the toilet, then offers a firm shoulder to lean on while she's slouching in the shower, then out comes the lotion and mainstream America has officially exited the theater. But this compromising disarmament and seduction are symptomatic of a greater Weltschmerz drawn from Ray's inability to tear himself from the friendly neighbors, the omnipresent television set, the late night beer chugging with intolerable tech school friends...all the insufferable trappings of suburbia. It's these banalities that make the movie's transgressive taboos - abuse, rape, incest, attempted murder and suicide among them - seem like just another part of the growing process. At Ray's lowest point, after bluntly informing his friend that he just tried to strangle his mother to death, the sensible response he's given is: "I guess it's time to get out of the house then, huh?"

Russell claims this movie was made for about 15% of the population, not the usual criteria when selecting the subject of one's first film. That kind of fearlessness made him one of the most respected and enduring of the 90's indie darlings, but it's his incredible sensitivity to said material that put Spanking the Monkey on this list. Russell displays a maturity (he was in his mid-30's when he made the movie) in presenting these difficult topics that concentrates on the impetus behind the characters' lapses rather than the acts themselves. As a result, the misconduct on display comes off more funny than appaling and feels absurdly relatable. Which isn't to say Russell condones the mother-son tryst as "right" or "purifying" a'la Murmur of the Heart; while nothing is ever presented as anything but absolutely wrong, they just happen to seem like the natural progression of events in these peoples' lives such is Russell's deft and careful approach. He eschews provocation for shock value, setting him apart from contemporaries such as Todd Solondz and Alexander Payne, or visual cleverness for its own sake, thus avoiding the less successful tactics of a Wes Anderson and Spike Jonze. Rather than the guns and dick jokes that were staples of low budget American features at the time, Russell instead reflects on the kind of quiet and insidious moments that made the best of 90's independent cinema stand out. Moments in Monkey suggest the "scenes inbetween" of conventional Hollywood movies, like what that horndog Hitchcock wanted us to think about when Grace Kelly closed the shade in Rear Window (Alberta Watson and her leg cast the obvious stand-in for Jimmy Stewart's hobbled voyeurist.) Discomfort and shame and serious brooding may at the heart of the movie and the comedy itself isn't exactly light (it elicits anxious snickering rather than belly laughs - the "boner boat," for example, is as clever as it is cringe-inducing) but its nauseating atmosphere is almost equally nostalgic. (It also employs traits of a great horror movie - you keep thinking "Why doesn't he just get out of the house?")

The one constant in Russell's varied work over the last 20 years is family, and the function of people within confined groups. Watson's emotionally needy mom has been reflected in his films by Mary Tyler Moore's bra-flashing adoptive parent in Flirting with Disaster, Talia Shire's domineering mom in I Heart Huckabees and Melissa Leo's controlling matriach in The Fighter. All played a hand in negatively effecting their respective son's behavior, although each would inarguably claim to have acted out of concern for their offspring's best interests. In the case of Watson, she's reacting out of fear of losing the intimacy with her son which she's already lost with her husband, a rowdy, philandering bully who guilts Ray with familial obligations - "We all have to give a little back sometimes" - that are blatantly hypocritical. So her motivation for manipulating her son's affections, partly due to boredom though increasingly out of desperation, comes off as almost pitiful as she lie there bedridden, the blue glow of the television illuminating her head like a suburban saint; being protective of Ray and being jealous of Ray have become almost indistinct from one another in her mind. But since she's so confident and sexually dominant, the father graviates away from the house and becomes estranged while the son is constantly sucked in and can't escape, giving up his freedom and even privacy as the family dog frustrates his attempts to lock himself in the bathroom and paddle the ol' primate. You really can't go home again when home has become a breeding ground for guilt, emasculation and victimization.* Ray's ultimate solution is to throw himself off a cliff into a quarry only to surface on the other side, leaving his parents and their home behind and getting on with his life, as the Morphine song suggests, "in spite of" their negative influence.

When people point to the debuts of American indie auteurs in the 90's, what's apparently been "lost" in American films since then, what I think of is the complexity of Russell's shrewd non-confrontational confrontation: his willingness to be controversial by not being controversial. While the movie has an undeniable 90's feel to it - just line up the posters to this, Swingers and Go and you'll see what I mean - its timelessness in terms of the eternal constraint of family responsibility and sexual confusion of the American male are the reason Russell is still heralded as one of the more original and audacious of filmmakers from the second Indie wave.** It's nice to look back at a time when the careers of new directors were bolstered by genuine talent, when Jeremy Davies still looked relatively healthy, and classic movies could be made for under $100,000.

* Actress Carla Gallo was probably not personally traumatized by what her character goes through in the movie (roughly handled by a groping Ray, slapped across the face by his jealous mom), but Judd Apatow seems to think she was, casting her as "Toe-Sucking Girl" in 40 Year Old Virgin, "Period Blood Girl" in Superbad and "Gag Me Girl" in Forgetting Sarah Marshall. Her frustrated attempts at seduction and feminine humilation in these films seem directly related to her role in STM.

** Just as a side note, I'll say it's kind of unnerving that Three Kings didn't make the top 50...not sure how that happened. I like Spanking the Monkey better, but I would have voted higher for Three Kings had I thought it was in danger of not getting enough support from my fellow 'smokesters.

32. DAYS OF BEING WILD (1990, Wong Kar-Wai)

christopher funderburg

The films appearing early in this Top 50 List have tended to be either singular achievements by inconsistent artists (Bad Lieutenant, Black Robe, Last Night, even Out for Justice if you want to treat Steven Seagal as an actor-auteur) or the confirmation of a world-class talent (Ratcatcher, The Insider, Life is Sweet.) Bruce Beresford made a few great movies and more than his fair share of awful ones, but he never made another one like Black Robe. Before The Insider, Michael Mann created stylish, enjoyable films but his work was infamous for its cheesiness as much as anything - Manhunter, Heat and the Miami Vice t.v. show wouldn't reasonably point towards his late career redefinition as stylistic innovator and master of the true-life epic. The early entries on the list are a mix of films from filmmakers one might be reasonably hesitant to over-praise and films from filmmakers at the moment when they jumped to greatness, but not their greatest artistic achievements.* Days of Being Wild falls into the latter category, the moment when Wong Kar-Wai made it thoroughly clear his work could stand toe-to-toe with anything out there, the arrival of a world-class artist, the jolt of shock that greets an audience when they first come into contact with a breath-taking and original talent. Wong's debut feature As Tears Go By pretended to be another Hong Kong bullet ballet in order to get funding (seriously, watch the trailer for that thing), but it was fairly clear that Wong wanted to say something else with his art. With Tears, just exactly what it was he wanted to say remained entirely mystifying - it's obviously the work of an artist striving to express himself, but who the hell knows what he's trying to express?** While Days of Being Wild didn't entirely eschew genre elements (it does climax with a massive knife fight that erupts into a shoot-out), it clarified what Wong was after: the elusiveness of human connection, moody visual reveries anchored by ironically employed pop songs, sensualism and implacable longing for a new existence, a new universe. It also solidified his relationship with a handful of actors including Leslie Chung, Maggie Chung and Tony Leung (who appears in a truly wonderful and baffling cameo to end the film) - Wong hasn't since made a feature film without at least one of the three involved. Leung's genuinely mystifying appearance somehow feels cosmically right even if he doesn't appear in the film until the final scene, isn't connected to any of the other characters and does nothing beyond get dressed up for a night out in a cramped apartment with a ceiling so low he has to do everything hunched over. He also appears to be some kind of a card shark. Wong claimed he intended the moment was a set-up to In the Mood for Love, but even if that isn't necessarily true, what the strangely drawn-out, inexplicable ending makes clear is that if it's a Wong Kar-Wai movie, Tony Leung Chiu Wai's effortlessly captivating presence will loom over it.***

Equally importantly, Days marks Wong's first collaboration with shambolic Australian cinematographer Christopher Doyle, whose stunning images shift fluidly between chaotic and dreamy in a way that gives not only expressiveness but gravity to Wong's wistful romanticism. Wong trades in quiet longing and over-whelming sensualism - Doyle's visual power makes those element palpable even when the plot turns oblique.**** Days features a handful of the most lovely close-ups ever committed to celluloid, the early moments of Maggie Chung and Leslie Chung in post-coital repose are unforgettably gorgeous. The humidity sticks to their skin while the soft shadows of the evening play off their features; a fan blows gently, restlessly nearby. We feel those moments, we live inside the world Wong and Doyle have created, we implicitly sense everything that needs to be known about the lovers, about their life and their existence. From the lonely halls of Maggie Chung's stadium soda shop to the green lushness of the Philippine jungle, Days invades your senses and leads you down a narrative path felt through intuition; it leads you along as a dream does, arresting your senses and inducing you to feel before you necessarily understand. Maggie Chung's sad midnight walks with Andy Lau's police officer wouldn't have the same emotional effect without the way Doyle captures the rain drizzling down on the sidewalks, the shadow from Lau's visor that conceals his eyes in darkness or the piercing close-ups of Chung's lovely, hopeless face. Mixed with the hypnotic imagery, the ironic use of pop music defies the standard ironic use of pop in film. Instead of contrapuntal contrast for a comic or even sarcastic effect, the cloyingly swooning music in Days gains sincerity when paired with Wong's characters and Doyle's visuals - the plastic and manipulative strains of Days' pop standards are rendered over-whelmingly romantic, evocative in spite of themselves. Days also proves that even if Wong's plots are oblique, circular or slow-moving, his ability to draw unforgettable characters and repeatedly punctuate his stories with devastating climaxes in miniature is rivaled only by the deftest of dramatists. Wong creates beautiful characters for the Chungs and Lau as well as Carina Lau and they reward him with searing performances - the low-key beauty of his story tied to their expressiveness. As Lau waits by the pay-phone for a call that never comes, in a few sentences of voice-over Wong delivers a minor tragedy as powerful as any I recall, a tragedy all more the powerful for its smallness, for its commonplace qualities. Days of Being Wild can lay serious claim to being Wong's finest film, even if that honor probably would ultimately fall to Happy Together or In the Mood for Love. What's not debatable is that Days is decisively the moment when Wong Kar-Wai became Wong Kar-Wai.

* The reason that Total Recall, Clockers and Naked Lunch fall so far down and appear so early on the list is that their filmmakers clearly made a half dozen films just as good or better - it's hard to get too excited about the excellent Total Recall when Robocop, The Fourth Man, Turkish Delight, Black Book and Soldier of Orange are out there for comparison. If anything, it probably unfairly causes it to be underrated next to Verhoeven's other masterpieces. What is Clockers next to Do the Right Thing, Crooklyn, 4 Little Girls and Malcolm X or Naked Lunch next to Videodrome, Dead Ringers, Crash and Spider? Total Recall, Clockers and Naked Lunch are all great films, but clearly not the best work their estimable filmmakers are demonstrably capable of producing.

** Wong should just stay away from genre filmmaking - his two other worst movies are the muddled, mush-headed wuxia pian Ashes of Times and the inert, wearying science-fiction disaster 2046. In college, I wrote a paper on Ashes of Time and tried to sort out a chronological time-table for the famously disjointed, impenetrable narrative. In doing so, I discovered at least two scenes that couldn't be placed, scenes in which characters referred to events that couldn't have happened yet based on where the scenes in question absolutely had to come in the narrative. It's a plot that is literally impossible to follow. Go ahead and argue that's Wong's intention, I'll be busy not giving a shit.

*** He might have even been able to fix My Blueberry Nights if Leung and Maggie Chung replaced Jude "gorgeous without charisma" Law and Norah "Lite Jazz" Jones. Certainly, Leung should have turned up somewhere. Unfortunately Leslie Chung died in 2003, so he didn't even have the option of bringing in the whole trio to salvage that mess.

**** Not to keep hammering Blueberry Nights, but absence of Doyle on that film is deeply felt - even a well-respected D.P. like Darius Khondji can't come within twenty-three thousand miles of replacing Doyle's synergy with Wong.

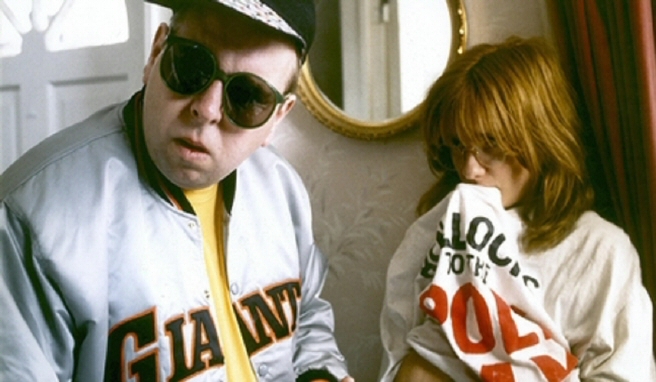

31. LIFE IS SWEET (1990, Mike Leigh)

christopher funderburg

There's a problem with assembling a Best of the Decade list such as this sweet baby: in a funny way, directors who made too many great films in the decade get penalized.* The excellence of Mike Leigh's 90's output almost certainly suffered the most from this vagary - of the 5 feature films and single 22 minute short he produced in the decade, only one film (Career Girls) could be decisively said to be undeserving of a slot in the Top 20. Because Leigh made four masterpieces - Life is Sweet, Naked, Secrets and Lies, Topsy-Turvy - the films naturally split votes amongst each other. Ask a handful of cinephiles which is their favorite and no clear answer will emerge. The Pink Smoke writers polled for this piece happen to be in unique agreement about which film is the best, but I know for a fact our choice wouldn't be universally favored among critics. But that's my point: no Leigh film is the consensus best when it comes to Leigh because they're all great. On top of that, when I put my list together, I felt strangely queasy about making a full 10% of my Top 50 Mike Leigh movies.** I mean, should I put my least favorite Leigh on the list (A Sense of History) or use that slot to offer up a little more flavor and variety? After all, I think all five Leigh movies are better than any wuxia pian from the 90's, but it doesn't make sense to have no wuxia on my list - I love that genre and it reached some pretty exquisite heights in the 90's. So, should I include my least favorite Leigh or my favorite wuxia (The Swordsman II?) Or how about giving some love to a Henenlotter film like Basket Case 2 that I can't in good conscience say is better than Life is Sweet? Should I go with five Mike Leigh movies or swap one out for a consensus classic that's obviously great but a film that I personally could care less about like Unforgiven? Several times I just threw up my hands and said "enough of this filmmaker or that one, let's get some variety in here." I suspect the other voters had to make the same kind of choices. Individual ballots of 75 films getting whittled down to the 50 ranked highest between the voters - you don't have as much room as you think to get in everything you love. Those kind of compromises and soft-headed reasoning are why I hate "The 10 Greatest Films Featuring Dogs Dressed Up like People!" lists or similar tabulations. Canons are inherently subjective, always miss a few of the inarguably best films and feature arbitray end-points (what, you don't give a shit about the 53rd best film of the 90's?) - plus, you'd have to be an ego-maniac to think your opinion is the correct one. Mike Leigh almost certainly made five of the best movies of the 90's. Don't expect to see them all on this list.

Pointless, pedantic preamble concluded, I'm happy to tell you that Life is Sweet made the cut in spite of all that noise if only because it remains the most "Mike Leigh" of all Mike Leigh's films, the platonic idea of Leigh's spectacular brand of unpredictable, hilarious, depressing domestic drama.*** The plot constructs itself by sprawling outwardly from a single household into a series of seemingly unrelated, meandering vignettes until building to an unexpected catharsis followed by a few quiet scenes of emotional stasis. The story rambles along, carried by complex, detailed performances and the ebb and flow of everyday life. There is comedy and pathos in equal measure, Leigh's dexterous dialog (developed in collaboration with the actors)**** contains as many memorable quips and quotable lines as a Marx Brothers movie, but the psychological components of the words are never undercut for the comedy. Leigh does kitchen sink realism with a flair for absurdity and gallows wit. There's surprisingly little cynicism in these film despite the fact that several of them will make you want to blow your brains out. That template I've just outlined applies perfectly to more than a half dozen of Leigh's eleven feature films: Bleak Moments, High Hopes, Life is Sweet, Secrets and Lies, Career Girls, All or Nothing, Happy-Go-Lucky, Another Year. As I mentioned in a footnote, Topsy-Turvy goes way off-model, but even still it has the unmistakable Leigh flavor. Vera Drake (a bit more somber and lacking in all but the faintest traces of humor) as well as Naked (relentlessly witty but also consumed by the lead character's restless cynicism - also, it's a road picture) are the only other two features to significantly veer away from Leigh's signature approach and they don't even stray that far. Life is Sweet, however, stays firmly rooted in the realm of domestic minutiae, chronicling the endless squabbles of the family unit while featuring a larger than usual dose of jokes. Most crucial to essential Leigh-ness is the inclusion of "the Mike Leigh special": an unflaggingly repellent ball of unfocused anger, resentment and desperation who takes their misery out on anyone around them, usually their family. The fat kid in All or Nothing, the abusive mourning nephew in Another Year, David Thewlis in Naked, the dyspeptic shiftless son in Meantime, the hair-dresser's daughter in The Short and Curlies, the driving instructor in Happy-Go-Lucky, the stringy-haired bulimic daughter in Life is Sweet. Leigh specializes in these kind of characters, the hopeless creatures happiness mysteriously eludes; in Life is Sweet Jane Horrocks plays quite an affecting variation on the theme.

The film loosely follows the attempts of Jim Broadbent to break free of his mundane 9 to 5 in an institutional kitchen by buying a rusted old hot dog truck to refurbish, but the story (like Broadbent's character) keeps getting hijacked by other concerns, most prominently Timothy Spall as a would-be high-end restaurateur. But even before the movie digresses to a long sequence following Spall's exploits, it keeps getting knocked off track by Horrocks as Broadbent and Allison Steadman's implacable daughter. She's a mess of nervous tics, out-sized pseudo-political sentiments and cutting put-downs. Anytime Horrocks appears on screen, she dominates the movie, her aggressive negativity and nasty commentary on her life and family stopping the story in its tracks. It's not that the family even has an extreme reaction to her anymore - her presence gets treated more like a faulty heater in the winter, an annoyance they can't ignore, but something that might as well be engaged with gentle humor and patience. Horrocks attempts to disrupt their lives, but she's simply an aggravation they have to live with as opposed to someone who makes them reconsider their existence. Steadman (Leigh's wife at the time) spews jokes, exaggerated reactions, chatter and giggles at every moment, her reaction to both Horrocks' misery and Broadbent's charms an identical nervous bellowing laughter and zippy musing - she almost seems like one of the little girls in her dance class blown up to adult size, over-flowing with energy but not quite sure how to usefully channel it towards her adult responsibilities. Broadbent delivers a more spirited and comic performance than I can ever recall the legendary actor attempting - not just the amazing monologue he addresses to the spoon that destroys his burgeoning career, but throwaway business like playing with a pair of porcelain dogs. Leigh carefully draws a portrait of a marriage you can understand between Broadbent and Steadman, one that began in their youth and sputters along more than a decade later, a union in which both parties are in love and managing to avoid driving each other out of their minds. I've scarcely mentioned their other daughter, a practical, tomboy-ish plumber's assistant played by Claire Skinner mainly because her personality is to have no personality. She's got concrete, unexciting plans to travel abroad, a steady job and very little to say. Leigh's implicit commentary contrasts Skinner vs. Horrocks: which would you prefer were your daughter? The staid to the point of non-existence lass or the one that hurls verbal violence in all directions all hours of the day?

With Life is Sweet, Leigh explicates his favorite theme: why are some people effortlessly happy and others not able to achieve happiness? It's hard to imagine Horrocks ever finding contentment - she's disgusted by her chocolate-spread intensive sex-life and shaky relationship with David Thewlis, in "getting ready for Naked" mode. She has no goals, no aims and in a devastating climatic confrontation with Steadman, she even has her tenuous illusions about being a politically motivated feminist shattered by Steadman's incisive commentary. Worse, Steadman pulls the rug from under the role that she's fiercely adopted, almost out of necessity: family provocateur. Steadman undermines Horrock's ideas about her role as a "daughter" and "beloved child" throwing down brutal truths about the nature of family and exposing to daylight the burdens and unhappiness of her mother that Horrock didn't realize existed. In the film's final moments, one of the placid conversations on which Leigh's films tend to end, Horrocks and her sister have a quiet discussion about their lives, their dialogue further exploding the theme of joy's mysterious nature. Broadbent's story provides yet another layer, his indomitable goofball seemingly able to overcome whatever obstacle life throws at him, a man naturally predisposed to looking on the bright side of things, a man unable to ever be fully crushed by the grind of life - the other extreme on a familial spectrum with Horrocks as his opposite polarity. It's easy to see how Steadman adores him despite his flightiness. The final piece in the puzzle Leigh assembles comes in the form Timothy Spall's weirdo hep-cat restaurateur. He affects a "with it" quality that seems transparently pathetic on first glance, but his resolve and self-confident patter could convince many a skeptic of his cognizance. A tubby, balding, pale dude who seriously dresses like Mars Blackmon in a couple scenes, Spall cuts an unlikely figure in his red convertible and with his ridiculous sounding dreams to open a high-end bistro called "The Regret Rien" that serves vomitous-sounding concoctions like tripe souffle, liver in lager and quails on a bed of spinach and treacle. He's the human representation of the power of hope, of the value of self-confidence, of believing against belief in your impossible dreams. To see how easily these dreams can be punctured, how pathetic those punctures can leave us, feels tragic right up until it turns ugly. In a flash, Leigh shows us how crushed hope can bring out most grotesque awfulness in humanity - even the man who has it all figured out is at heart pitiable and base in the face of fate's cruelties and his own self-deception. But that's the choice: the delusional dreams of tongues in rhubarb hollandaise or the lifeless reality being a plumber's assistant.

I'll make a little bit of a circle back to the beginning here in order to wrap things up: no one on the planet (and possible not on Omicron Persei 8) makes films like Mike Leigh; not his inscrutable, collaborative development process but also in terms of the ideas and thematic obsessions to which he returns over and over again. It's a cliché to write that Leigh's films feel breath-takingly close to real life and then expound on their unique rhythms and cadences, tones found nowhere else in cinema and only encountered outside of movie theaters. Or, I'm assuming it's a cliché because Roger Ebert's done that and he's basically a cliché machine.***** Anyhoo, Mike Leigh: there's nobody like him and even his films that are mediocre compared to his overall body of work are 2.3 billion times better than just about anything out there. It's hard to believe that the film I described above clears the bar of "competence" let alone works flawlessly and contains humor and emotion in equal measure with a host of brilliant performances and never sacrifices ideas to make the story "flow better." Leigh refuses to pare away the troublesome elements of his style, forces aesthetics to take a backseat to characters and themes, never strives for slickness or convention. He blows up cinema in film after film, establishing himself as one of the truly unique artists in the history of the medium. I defy you to find a filmmaker in this world or the next who can make a movie like Mike Leigh. There hasn't even been a filmmaker like him and I suspect there never will be - forget monkeys: you could have a thousand Palme d'Or winners sitting behind a thousand cameras for a thousand years and you'd never bring together a character like Horrocks' troubled bulimic, never get a deft and wily performance like Broadbent's, never get a scene like the mother-daughter reckoning that erupts late in Life is Sweet, nor a moment like the final shot of this brilliant dissertation on family, work, dreams, desperation, drunkenness, sex, self-hatred, happiness and unhappiness. They might write a few good one-liners, but that dialogue would only be so much clever trash if it didn't come out of one of Leigh's character's mouths into one of the singular, peculiar, all-too-real worlds he devises. It's unfair and ludicrous that I decided I should only choose two or three of his films for my list. But Spall's would-be prune quiche impresario proved how difficult it is to regret nothing - it might seem like an inconsequential regret that a Leigh title or two gets left off of this Top 50 Best Films of the 90's list, but like Leigh's other work, Life is Sweet proves it's the inconsequential regrets that make up an unhappy life.

* Similarly, eclectic and prolific directors who don't specialize in masterpieces per se but churn out a ton of enduring films also get a little bit shafted. Miike and Linklater don't necessarily have anything that absolutely deserves to be on this list that didn't make it, but they were hugely vital filmmakers in the 90's. They'd both definitely crack a Top 50 Filmmakers of the 90's list.

** I seem to be the only voter who included short films, which is ludicrous bullshit: Sanctus and The Wrong Trousers are as good of films as were made in that decade or any other - shorts films deserve their rightful place in cinema history and the continuing critical dismissal of their importance irks me to no end. The irking literally will not end!

*** By a mile, the bouncy, biographical period piece musical Topsy-Turvy takes the cake for most off-model.

**** There's a lot of misinformation out there about how Leigh "devises and directs" his films and Leigh considers his process proprietary, so there's no way to know exactly how much of his work is improvised, how much the actors are involved in the creation of their characters and how much (or what) Leigh writes down in advance of his months-long developmental workshops.

***** Except when he's pretending to be Garfield. [Ooh - Jane Horrocks did a voice in that movie! -- ed.]

CLICK HERE TO CONTINUE WITH #'s 26-30

RELATED ARTICLES

home about contact us featured writings years in review film productions

All rights reserved The Pink Smoke © 2012