MOVIE SHELF: COMPARING FILMS TO THEIR LITERARY COUNTERPARTS

christopher funderburg

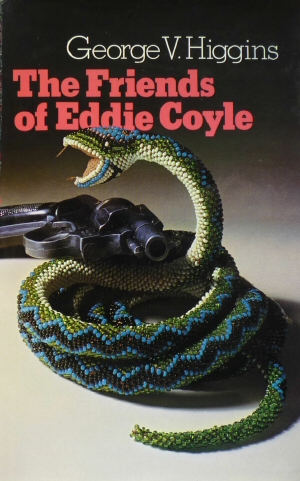

PETER YATES' THE FRIENDS OF EDDIE COYLE

based on THE FRIENDS OF EDDIE COYLE by GEORGE V. HIGGINS

Welcome to Movie Shelf, a series that compares the films on our dvd shelves to the novels on our bookcases. We at the 'smoke have always been fascinated by screenplay adaptation: what a script writer takes from the original source material, what he changes, how the two different works vary from each other and what the existence of the movie itself says about the book and vice versa. All this and more will be examined in this ongoing line of articles.

I ran into Film Comment Editor-at-Large Kent Jones a short while ago and mentioned to him that coincidentally I had just been reading his excellent liner notes for the Criterion edition of The Friends of Eddie Coyle. We're screening the film at the Jacob Burns Film Center as part of a larger series of crime novels-turned-movies and I brought up his liner notes as part of pitch to get him to actually come speak after one of our screenings. We talked for a while about how awesome Peter Yates' 1973 film is, but after a moment I said "That film is great. But the book is -" And he interjected "- something special." We both agreed that the film works, but that the book was something else altogether, something richer and rarer than the film. That's a fairly usual problem: great novel, notably inferior film. And I guess you could file Eddie Coyle away in those terms and be done with it. But I think the situation with the book versus the film in this particular case is actually a real rarity: excellent film, unique novel that definitely isn't the film. It's not even that assistant D.A.-turned-author George V. Higgins novel is great, it's that it has a singular voice and perspective that's shocking even now - I can only image how it felt back in 1970, what an eye-opener it must have been. Elmore Leonard said it taught him how to use profanity in dialog, for fuck's sake.

If The Friends of Eddie Coyle was not a game-changing novel for the crime genre, it is only because it represented the furthest the form could go in a certain direction. It didn't redirect the flow of the genre only because it followed a single, long-trickling tributary to its decisive end. From its inception, the hard-boiled novel has been defined by its language; not the language of its omniscient narrating authorial voice, but the language of its characters. Dashiell Hammett threw down the gauntlet with his bold use of slang - it's tough to imagine a time when simply having a character say "yeah" would have been considered radical, but keep in mind, Hammett was rebelling against his contemporaries coming out of the prim and proper British Mystery school, against would-be Agatha Christies and their eloquent, brilliant Hercule Poirots unraveling the clever-enough-to-be-idiotic criminal plots. These books and their "Dear sirs, if I mayhaps propose an unorthodox but irrefutable solution to this ignominious assassination: it was not a single man in this house who committed these crimes, but everyone here in this house!" would be blown to smithereens with Hammett: "Burn them out, Fat" and then gangsters dynamite the place and shoot the surrendering survivors down in cold blood, in broad daylight, in front of everyone.

Hammett's work, of course, can get absurdly slangy and time has undoubtedly diminished a bit of what likely felt like realism to stunned readers in the 1930's. His most enduring creation, the charming detective duo Nick and Nora Charles, definitely feel of their era (in part because they helped define one corner of it) even with their timeless excessive alcohol consumption and cynicism-tinged irreverence. As characters, they're a rebellion against the dourness and absurdity that followed in the wake of Edgar Allan Poe's detective stories and Sherlock Holmes' plausibility-antagonizing plots, but don't quite escape the larger shadow: with Hammett and his equally influential So-Cal follower Raymond Chandler, the criminal plots are more blunt and brutal, but no less extravagant and convoluted. Their dialog, the striking stylization of the way in which their characters speak, more or less put to bed the previously dominant style: following Hammett, crime novels were defined by the way their characters spoke. The realism of their speech, of their slang, sent the genre down a path towards authenticity - authors got the idea that realism was what Hammett's readers were responding to, so they copied it with brutality and ugliness sometimes standing in for realism; slang, cynicism and violence as a shortcut to "reality."

And oh Señor Pink Smoke reader, The Friends of Eddie Coyle is a book in which the characters speak. It's frequently described as consisting of almost nothing but long sections of dialog - that's certainly true of its follow-up and semi-sequel Cogan's Trade (recently adapted into the excruciating Killing Them Softly) but a bit of an exaggeration with Friends. Friends still has a fair amount of descriptions of people and places and small bits of active business like the opening scene where Coyle doubles back through a supermarket to make sure no one is following him to his snitchin' appointment with a cop (named Dave Foley?)* That nitpick aside, it is a dialog-heavy novel. Probably as dialog-heavy as a novel can be without becoming unreadable (and make no mistake, some of Higgins' subsequent stuff borders on unreadability precisely for that reason.) The Friends of Eddie Coyle took the definition of the genre put in motion by Hammett in the 1920's to its logical extreme: by authentically reproducing the roundabout, profane, frequently inane conversations of low-life criminals, an exacting realism could be realized in regards to the criminal world, the nature of crime and those who commit it. Higgins purportedly replicated large swaths of dialog verbatim from his time as criminal lawyer, conversations which he had both participated in and overheard. And the realism of it, of its mundanity, circular logic, restlessness, ball-busting and outright stupidity still hits with the impact of a sledgehammer - it's not a book that will blow you away, it's one that will knock you square on your ass. It's like getting cold-cocked in a bar fight that you didn't realize had started already.

But there's an essential modesty to the book. Eddie Coyle is a small-time middleman and the plot more or less follows his attempts to weasel his way into a job snitching for the cops so that he can avoid doing a small bid for transporting stolen property. Based out of Boston, he's got a grand jury hearing up in New Hampshire in a couple weeks concerning a mob truck full of Club Canada he was caught driving and he's not looking to go back in the joint even for a couple years. The cops don't particularly give a shit about him - he's a stocky clown who never provides them with any useful info. And he's a nobody: his main activity in the book is acting as a middleman between a group of bank robbers and a gun dealer. He doesn't rob banks himself and you don't get the impression any of his compatriots think he's much use. He's nicknamed "Eddie Knuckles" because he got his hands smashed in a desk drawer as retribution for previously screwing up this simple task of acquiring legit, more or less untraceable firearms. Jackie Brown, the gun dealer, comes across as the savviest (certainly hardest working) of any of the knuckle-headed crooks traipsing through the story and I'm not sure Higgins cares if you're rooting for him or Coyle when Mr. Knuckles sees him with a trunkload of machine guns and decides to sell him out to the cops. The book has a startling matter-of-factness about it, a total lack of magnetic or charming human beings, no Nick and Nora Charles spouting one-liners or Philip Marlowes wryly commenting down at the underworld as they maneuver just above it all.

Reading the book, you get the sense, finally, that this must be what the criminal world is like. No embellishments. No horseshit and gunsmoke.

Again, it's the dialog that hooks you: the endless conversations recounted therein are frequently hilarious, strange or grimly compelling. The nuts and bolts of the small-time wheeling and dealing proves hypnotically fascinating, an insider's tour of a world relentlessly portrayed on television and in the movies and in other books but never with this level of truthfulness: this is how it works. So what if Eddie Coyle isn't much more than a callow idiot and the bank robbers are the kind of dull, casually misogynistic jerks you'd go well out of your way to avoid in real life? I've always thought that liveliness is one of the most overlooked (and mysterious) qualities an artwork can possess; that "jumps off the page" quality commonly associated with the crassest and most calculatingly manipulative entertainment, but really shared by almost all of the most enduring novels and films ever created; what are centuries-old evergreens like Jacques le Fatalist and Gargantua and Pantagruel if not lively? Coyle achieves a peculiar brand of liveliness, one in which the monotony of dullards leading depressing lives jumps off the page through the sheer force of the authenticity of their behavior. The book is alive in some strange way, lively for its aliveness. There's no way that Higgins intends for you to like any of the characters in his book, not even the cops, but the overall effect is charming, compelling, page-turning stuff about the minute details of acquiring a cache of machine guns from drug-addled soldiers to sell to clueless hippie-militant types.

As much as Hammett and Chandler were characterized by their cynicism (the word "hard-boiled" itself meant to describe a type of emotional deadness shared by those new-style detectives), it would be tough to describe Coyle as cynical. It's too casual and mundane - a cynical worldview would throw everything off balance. It's simply a plain view of the criminal world, those whose job it is to operate outside of the law. No heroes, no villains, no wiseguys, no brilliant detectives or amoral badasses. Higgins puts on display men with, yes, a natural toughness and inarguably a comfort with violence, but not tough guys. A man like Donald Westlake's classic unflinching badass Parker character couldn't exist in the world Higgins has explicated, nor could a smart-mouthed moralist like Philip Marlowe. The criminal plots lack extravagance - with its depictions of bank robberies, the book could I suppose be located within the burgeoning caper genre of its era, but its crimes' straight-forward simplicity couldn't have less in common with those books' (and films') essential outlandishness. It might also be tempting to describe Coyle's world as amoral, but these men are deeply bound to the system of moral codes as enforced by "the boys back in Providence." There's a criminal code, not one involving honor, but the understanding that if you fuck up, you will get your hands smashed in a desk drawer. Nothing personal or nothing. Coyle weasels around with this code and thinks he's found a decent mark in the unaffiliated Jackie Brown, the book's closing irony a moral comeuppance for Coyle based on codes he truly didn't violate. Higgins does a great job of pulling apart the moronic mechanics of the thought process that leads to Coyle's demise, the mistaken notions of "truth" and "what must have happened" that put a bullet in the back of the wrong guy's head.

* How come no one on the internet has cut together a wacky scene with that clip of Robert Mitchum walking up to a pay-phone, making a call and demanding "quit farting around, get me goddamned Dave Foley" followed by some hilarious clip of Dave Foley in a Kids in a Hall or News Radio sketch chatting back at him? This is what the internet is for. This is why our government decided Youtube can't be sued for egregious copyright violations: so we can do shit like this. Get on it, kids.

<<Previous Page 1 2 Next Page>>

home about contact us featured writings years in review film productions

All rights reserved The Pink Smoke © 2013