AGAiNST

AUTEURISM

c.a. funderburg

All this month, The Pink Smoke will be delving into the inarguably excellent but strangely undervalued work of French-expatriate Jacques Tourneur. From his hand in creating the Platonic ideal of film noir with Out of the Past to redefining the horror genre by focusing on its psychological elements with Cat People, Tourneur's role in cinema history is substantial and (get this!) multifarious - so, why isn't his name uttered in the same breath as Howard Hawks, Tod Browning or even Edward G. Ulmer?

By exploring the filmmaker's body of work, The Pink Smoke hopes to shine a light on the filmmaker's influence, introduce readers to some of his more overlooked films and make a case for why you (yes, you!) should mutter his name in your canonical exhalations - or at least nod your head in thoughtful appreciation every time his name comes up in casual conversation at your local Carl's Jr./Hardee's.

{PiNK SMOKE PODCAST: BERLiN EXPRESS}

{THE MOViE SHELF: NiGHTFALL}

{NiGHT OF THE DEMON}

{SECOND CHANCES: OUT OF THE PAST}

CAT PEOPLE

jacques tourneur, 1942.

CURSE OF THE DEMON

jacques tourneur, 1957.

AGAiNST AUTEURiSM

Everybody wants to believe in Genius, but more to the point, everybody wants to believe in the Genius behind the thing they love.

There is an ongoing debate, that’s deeply important to a certain kind of cinephile, as to who directed 1982’s spooktacular spook-a-rama Poltergeist. The debate pits credited director Tobe Hooper against writer/producer Steven Spielberg - and though I’m exactly the kind of cinephile who is deeply caught up in the battle, the plan right now isn’t to settle it or even engage it in terms of specifics.

What I’m caught up on is that there’s a strangeness to this argument: the dispute is over the word directed. Was Spielberg the one who really directed Poltergeist? It’s not enough that he unquestionably co-wrote and co-produced the film - there is a desire to see him given a proper authorial credit derived from the designation “director.”

This subliminal signal is transmitted from what the auteur theory has become, which now is more or less taken to mean the “director is the author of the film in the exact way a book has an author.” Is this true? To me, the Poltergeist debate hinges on an imagined conflict that doesn’t need resolving: Steven Spielberg can be a strong authorial voice heard in the film in his capacities as a writer/producer and Tobe Hooper can be a strong authorial voice heard in the film in his capacities as a director.

The bizarre idea that film criticism unconsciously lives under is that in most if not all films there is a lone artist that is the True Creator of any given film. Any other artistic voice on the film is subjugated if not superfluous. There is the Genius behind the film that I love. Conversely, I suppose, is the idea that there’s an Idiot behind all the films I don’t love. But this artistic voice controls, dominates, coerces all the other artistic voices on the film.

This is a bizarre idea if only for the reason that film is both the most collaborative of all mediums and the most expensive and, therefore, the most constrained by non-artistic concerns. Things we know to be true: the lead actor is the most powerful artist on any given film set while those in control of the money control the very existence of the artwork starting with whether they grant one of their employees the token concession of “final cut.” There’s no reason why the director should be taken as the default author of any given film, but that’s the way it is.

The things I’m writing are so obvious that I’m sure many of you will be tempted to dismiss them as irrelevant… and then continue to organize your interpretation and understanding of film under a falsehood in direct opposition to the obvious and irrelevant truth. The obvious truth is irrelevant because some framework is necessary for discussing the meaning of Game Night or Phantom Thread.

Somebody’s gotta be the author, right?

Would you ever answer “no?”

Why not? Why are you instinctively against the idea that films, in general, don’t have a single author the way a book has a single author? Why can’t you accept in your heart that most cinema is a confluence of separate artists’ ideas, business concerns and happy accidents? Why don’t you want to acknowledge that conflict, disagreement and compromise are elements of nearly every film production? The answers to those questions are obvious and irrelevant, so let’s shift focus to the root of all this.1

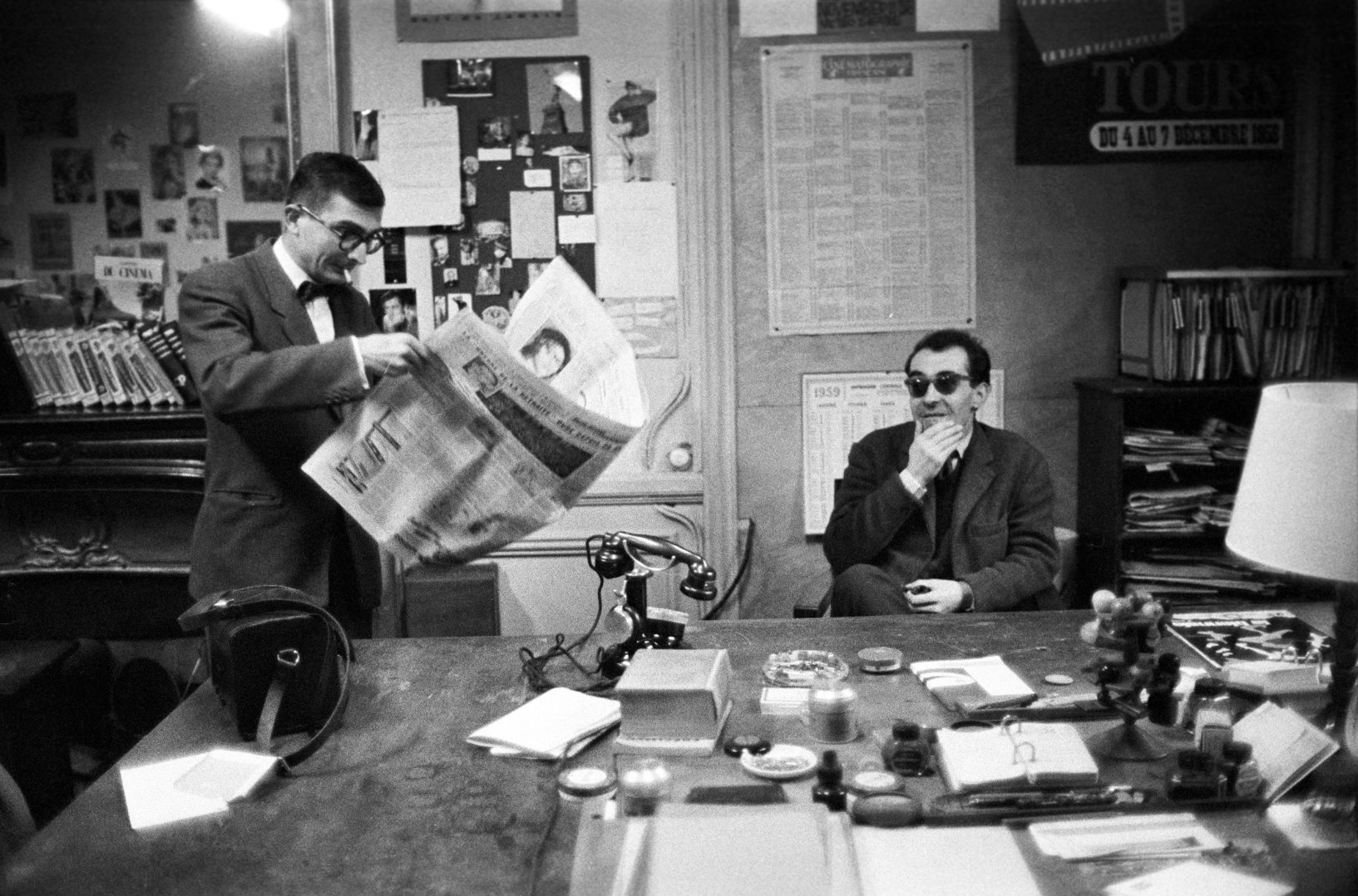

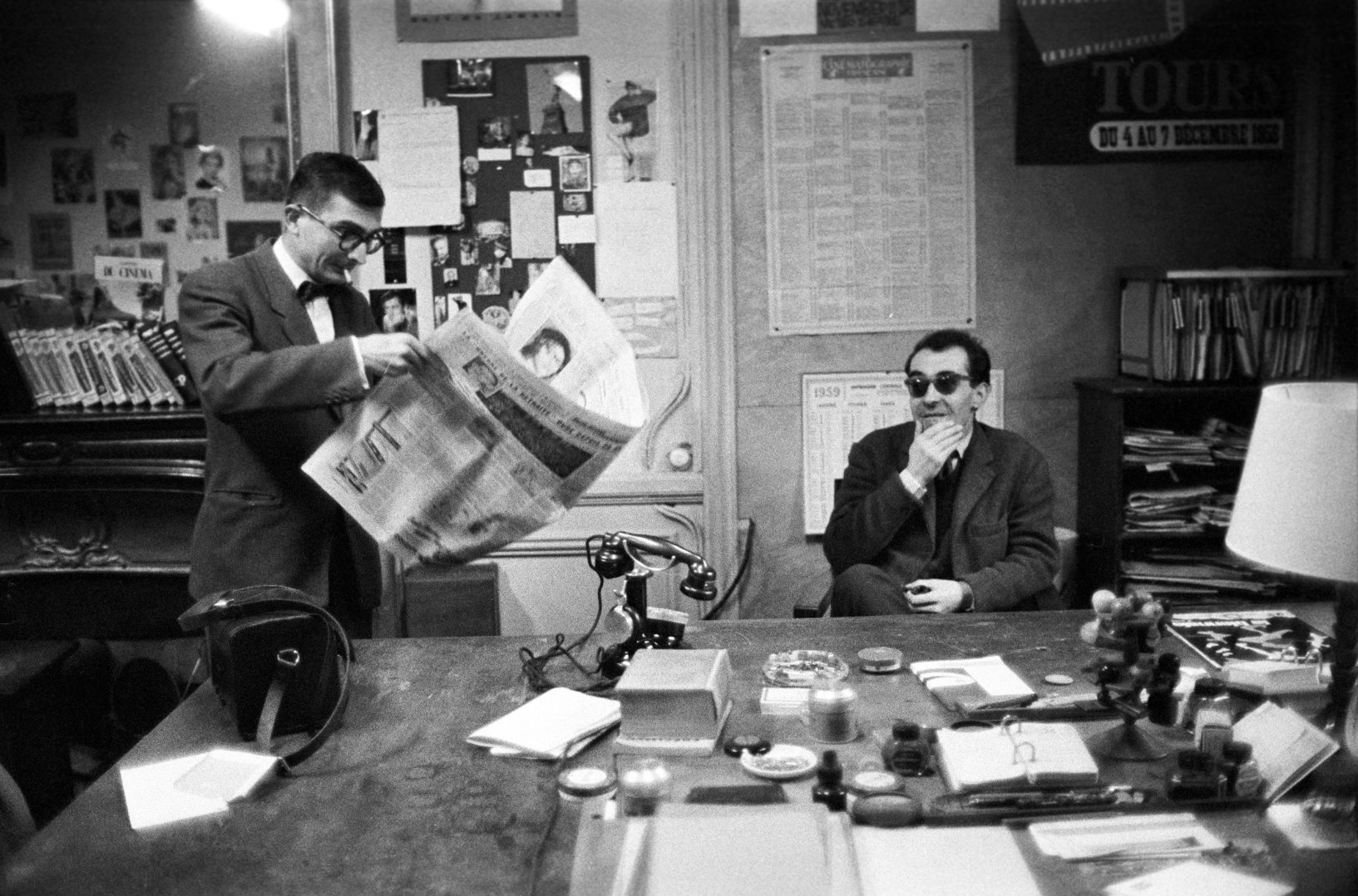

One of the problems of the auteur theory is that it was put forth by the Cahiers du cinema critics who were capable of breath-taking intellectual dishonesty, intentional misreading of cinema history, capricious self-contradiction and poetic pontificating that doesn’t make much sense if peered at too closely - a mess that Frank Tashlin described as “all this philosophical double-talk” (in reference to all the compliments they were throwing his way!)

And for the last 70 years, the Cahiers work has been peered at very, very closely. This is because it’s great! There’s no film writer I decisively prefer to Truffaut, it’s hard to imagine cinema without Andre Bazin, the book on Hitchcock by Rohmer & Chabrol is my favorite work ever written focusing on a single filmmaker. You can enjoy a hymn without becoming a convert - hell, you can get real goddamned meaning from a sermon without a measure of faith even the size of a mustard seed.

Even if you love those fellas, the fact is that the auteur theory has been watered down to something meaningless in part because the Cahiers du cinema critics were prone to presenting open-ended and self-serving ideas in most of their work. We end up with a stupid “the director is the author of the film in the exact way a book has an author” version of the auteur theory in part because their conception of auteurism has an elasticity and (feigned) guilessness built into it.

Take for example the idea of Howard Hawks: Auteur. Howard Hawks as a prime example of a filmmaker receiving a designation of “auteur” for no solid reason beyond the fact that the Cahiers du cinema critics really liked a lot of his movies. And maybe now, you are conjuring in your mind an idea of a Hawksian film, of groups of men cramped together engrossed in tense and intense work - which doesn’t apply to I Was a Male War Bride, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, Land of the Pharaohs or even his take on The Ransom of Red Chief.

So maybe now you’ve flipped in your mind to a “yes, but the Hawksian woman!” of The Big Sleep, Bringing Up Baby or His Girl Friday? What do those characters have in common? Stop and think about if those characters actually resemble each other than in the most broad and vague terms. What do those characters do that defy their genre archetypes from screwball comedy and film noir? If you’re writing for the Cahiers du cinema, you tie yourself in knots trying to harnass Sergeant York to Twentieth Century and then declare yourself the winner when your opponent gives up in exasperation. Part of the Cahiers trick is their unassailable grasp of minutiae: they can undermine what might seem obvious in the big picture (e.g. I Was a Male War Bride has fuck-all to do with Rio Bravo) by overwhelming their debate partner with an array of minuscule details and counter-intuitive interpretations of things people barely remember about these movies.

Compare Hawks to Preston Sturges: one has an extremely consistent style and mindset, the other does not. But that’s the weird second thread of the auteur theory, that gets lost more often than not: the impetus of the theory was not to use it to describe obvious artists with an inarguable authorial voice (like, say, Jean Cocteau) but out of a desire to give credit to less obvious “authors” like Hawks, Nicholas Ray and John Huston.

And so the very idea of it is all this philosophical double-talk: you, dear reader who has failed to do the work of a close-read, can’t tell that these filmmakers who are the inarguable author of their films are the authorial voices for the exact reason we must give them credit. The idea is appealing but also pernicious: it gives short shrift to screenwriters, producers and, most importantly, actors. Again it seems obvious to write it, but the overwhelming majority of the time, a Cary Grant movie is primarily a Cary Grant movie despite who directed, produced and wrote it. But “Cary Grant: Auteur” is an idea that far more people would bristle at than “Howard Hawks: Auteur.”2

Let me be doubly clear: my argument is not that Only Angels Have Wings and Scarface have nothing in common and that Hawks has no artistic voice; my argument is that he’s obviously (obviously!) one of several artists shaping the film and that Cary Grant, Howard Hughes and Ben Hecht all have important artistic influence over the films.3 These are meaningful voices in the creation of these artworks and declaring one the author, the authority over the others, the auteur is weird.

It’s weird to the point of being counter-productive. The noxious subconscious back-half of the auteur theory is that the less defined the director’s authorial voice, the more trivial the artwork. Try to imagine a critic arguing for the absolute greatness of an artwork while arguing that there is no auteur behind it. Because that’s what I’m about to do!

In honor of the Cahiers du cinema critics, this has all been a circuitous build-up to my point: Jacques Tourneur is not an auteur, but he still should be a filmmaker you adore.

Tourneur is an interesting case study for the argument I’m caught up in because he happened to have directed two of the finest horror films ever made, 1957’s Curse of the Demon and 1942’s Cat People - a pair of films that are almost diametrically opposed in their artistic philosophies, a pair of films where it is tough to argue their director is their auteur in any meaningful sense but are nevertheless masterpieces. It would be disingenuous to rob Tourneur of credit for having directed them but simultaneously there’s no way to designate him as the True Author of either.

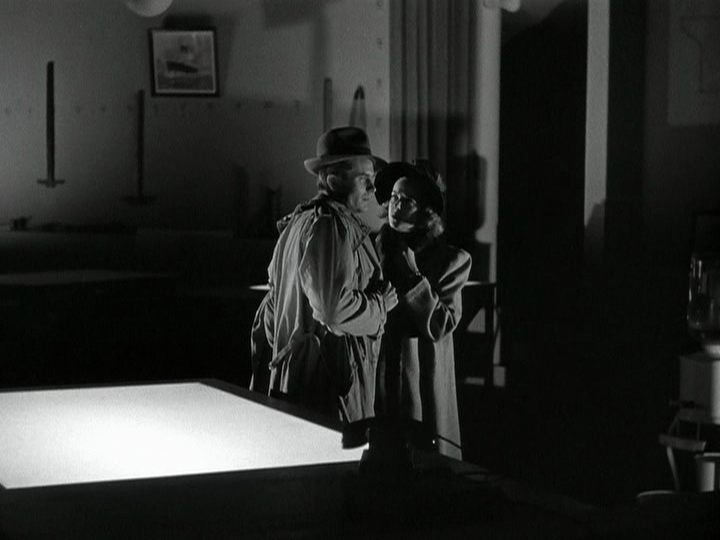

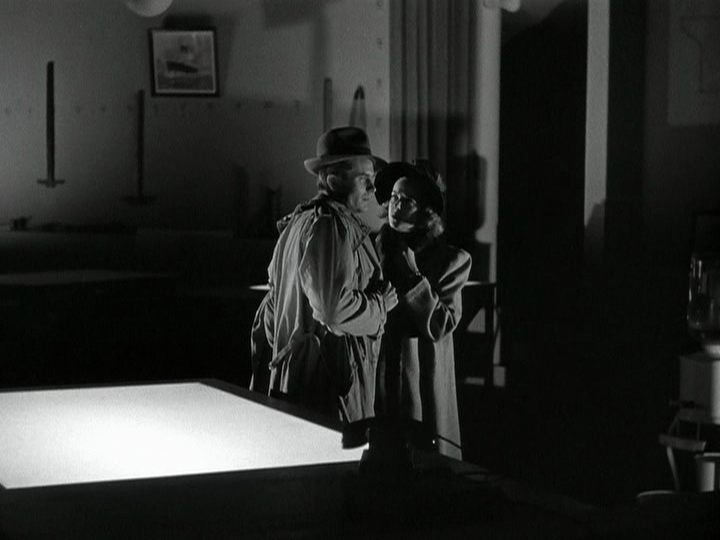

On Curse of the Demon, Tourneur and screenwriter Charles Bennett notoriously had major artistic decisions forced on them by the producer of the film, Hal E. Chester. The story follows a skeptical American psychologist investigating the supernatural powers of Satanic cult in England: Tourneur believed the legitimacy of the cult’s black magic should remain ambiguous, that the film should never fully resolved whether the demon they summoned was real or a phantasm fueled by fevered paranoia.

Chester believed the demon should eat someone within the first few minutes of the movie.

You can see Tourneur’s ideas at work in the film - his use of smoke and wind, of ambiguous shadows and eerie darkness builds a tension that is both immaterial and alive with terror. Conversely, the film also frequently goes alarmingly over-the-top with a pulverizing artless excess that is quite effective; Chester, Bennett & Tourneur each seem to be pursuing conflicting artistic impulses but it’s not to the detriment of the film. A director’s job is, frequently, to synthesize the conflicting artistic impulses of his collaborators, but Tourneur made clear many of the artistic choices in the film were not his, “The scenes where you see the demon were shot without me.”

This is not the case of a filmmaker placating a particularly annoying backseat driver, but of that passenger frequently leaning forward and grabbing the wheel. The situation got so bad that star Dana Andrews threatened to quit the film if Chester didn’t let “the director direct the film.”4 It’s an interesting mirror to the Poltergeist situation: a producer/co-screenwriter making on-set decisions to the frustration of the cast and crew. It’s natural for audiences and critics to want there to be a clear line between “collaborated with” and “undermined by” but that line frequently doesn’t exist - to take authorship of Curse of the Demon away from Tourneur and award it decisively to Chester would be ludicrous. To say that their conflicts resulted in a bad film would be untrue.

The usually unstated idea is that a compromised artwork like Curse of the Demon is a bad artwork, but cinema is an art built on compromise. Compromised cinema is cinema.

1942’s Cat People is the flip-side to Demon: an even better film, with even less conflict in its creation, where it’s even harder to attribute authorship to Tourneur. The film kicked off an astounding run of psychologically-oriented horror films5 in 1942-1946 from producer Val Lewton: Cat People, I Walked with a Zombie, The Leopard Man, The Seventh Victim, The Ghost Ship, Curse of the Cat People, The Body Snatcher, Isle of the Dead and Bedlam. There is a remarkable consistency to the aesthetic vision of these films despite their being directed by three different filmmakers (Tourneur, Robert Wise and Mark Robson.)6

In direct contrast of Curse of the Demon, producer Val Lewton insisted in all of these films that the “reality” of the supernatural threat should remain ambiguous: is Simone Simon’s character in Cat People possessed by a feline demon-spirit when she gets aroused or is that merely a paranoid fantasy created by psychological sublimation (as suggested by the great Dr. Louis Judd)? It’s a film where we never “see the demon,” so to speak, save for a fleeting and enigmatic effect in shadow near the very end of the film.

It’s not outlandish to suggest that Tourneur’s feelings about how Curse of the Demon should’ve been made were informed in part by how Cat People was made. His success under the supervision of Lewton created his conflict with Chester - Chester’s artistic battle with Tourneur is in some ways a proxy war with Lewton. But while it’s easy to credit some of the authorship of Cat People to Lewton, by all accounts throughout his career he spent very little time on set during the actual filming and stayed out of his director’s way - again, a marked contrast to the fights Chester and Tourneur had on set.

But Lewton was famous for his talent for punching up scripts, coming up with ideas for sequences, designing shots7 and creativity with economy in set design, costuming and special effects - he was immensely engaged with the artistic choices happening during pre-production, more so than is usual for a producer. So with Cat People, we have a film more in line with Tourneur’s professed artistic vision for Curse of the Demon, but a film for which he’s less deserving of authorship than that film where he was undermined by a meddling producer. Critically-speaking, what do you do with a filmmaker who directed two excellent films in the same genre, neither of which are his?

So, I’ve often wondered why Tourneur isn’t held in the same regard as Howard Hawks or Nicholas Ray or even Edward G. Ulmer when his films speak for themselves: Out of the Past, Cat People, Curse of the Demon, Nightfall, The Leopard Man, I Walked with a Zombie, Wichita, The Flame and the Arrow. This is unquestionably great filmmaking. The simple answer for why he isn’t held in massive esteem is that he’s not an auteur. Critics are uncomfortable with art where they can’t point to an author and assign genius (or stupidity) to that person.

Tourneur’s excellent work and meagre reputation are the perfect example: authorship of his very best films is given to Val Lewton. He didn’t make enough films noir for critics to build his identity around Out of the Past. His westerns aren’t as distinct as Ford’s or Hawks’ and the genre is out of favor, anyway. Can anyone connect together his best swashbucklers Anne of the Indies and The Flame and the Arrow as the work of a single visionary? His two best horror films are from alternate dimensions, artistically-speaking.

It’s simple, again maybe to the point of obviousness, but that’s why Tourneur doesn’t get mentioned as one of the greats. Because what good is an all-time great if he’s not the Genius behind the art you love? There’s a critical anxiety that almost wants to relieve itself by positioning the greatness of Tourneur’s films as a coincidence: if he’s not an auteur, there’s no credible reason for the consistent, over-arching excellence of his work. It’s an unhappiness: an artist and his work being diminished because of faulty ideas about his medium, ideas driven by impulses that are deeply unappealing to me.

There’s a pissing-contest smallness to debates organized around auteurism: my guy’s the best, my guy’s the smartest, the most talented, the greatest. The macho posturing around, say, whether Orson Welles is a genius wronged by the system or a bloated charlatan has a pathetic quality that I find touching now that I’ve been completely defeated by life. There’s something deeply human about getting caught up so much in identifying with an artwork, in projecting with such anger and indignity over a filmmaker. It’s beautiful how dumb these fights are.

It’s easy enough to say maybe you shouldn’t care about the person behind the plastic object in front of you,8 that the object itself is the thing, but it’s too human to care about the artist for me to believe in saying that. This is a winding way of writing “these debates are emotional as much as intellectual” while explaining why I’m completely sympathetic to them. As much as I want to be, I’m not above any of the things I’m critiquing, least of all emotion-driven irrationality.

Tobe Hooper did direct Poltergeist, goddammit. And Jacques Tourneur’s films are brilliant. Even if he wasn’t an auteur.

~ APRiL 3, 2018 ~

1 Take that, Straw Man!

2 There’s a reason they loved Hitchcock with all of his both real and semi-apocryphal “Actors are cattle” quotes. On a similar note, I started thinking about how actor pairings like Hepburn/Tracy or Dick Powell/Ruby Keeler or Wilder/Pryor indicate more clearly what a film will be than all but a few directors. Even luminaries George Cukor, Howard Hawks and Frank Capra are almost beside the point in the context of those sort of star pairings.

3 I’m also not arguing that auteurs absolutely do not exist in cinema: what else could you call Eric Rohmer, let alone Claire Denis or Hollis Frampton? But even then, Agnes Godard and Nestor Almendros and Alex Descas deserve to be credited with some meaningful measure of authorship over their work with those auteurs. Contrast this to a novel or a painting, is all I mean.

4 Bennett famously said of Chester “If he walked up my driveway right now, I’d shoot him dead.” (The Andrews quote is from Chris Fujiwara's Jacques Tourneur: The Cinema of Nightfall, the Bennett quote is from the Turner Classic Movies article on the film.)

5 It’s tough to describe some of these films like Curse of the Cat People and Seventh Victim as “horror films” per se, but at worst they’re horror-adjacent.

6 Gunther Von Fritsch is credited as co-director on Curse of the Cat People, though most accounts have him being fired from the film and emphasize his minimal contributions to the finished product. I don't know, I'm just going on what I heard from some guy. This guy I heard it from, he's probably got a degree from a college of some kind, which I think you'll agree is pretty impressive. I trust him.

7 The legendary “endless zoom-out” of the dying and dead in Gone with the Wind is famously something he came up with while working as producer David O. Selznick’s righthand man.

8 I’m thinking of Rene Clair’s quote to the effect of “Cinema remains a light, a white sheet and a strip of plastic.” I can't find the exact quote, so I might even be getting who said it wrong. Them's the breaks when you settle for a writer who does shoddy research.