SECOND

CHANCES

c.a. funderburg

Despite their sterling reputations, some films and filmmakers just don’t do it for us here at The Pink Smoke. This series, Second Chances, explores our attempts to grasp greatness where we’ve previously failed to find it; to actively make an effort to appreciate esteemed artworks for which we currently have an antipathy.

Jacques Tourneur month continues with this attempt to connect with Out of the Past, one of the defining films of the noir genre and possibly the French expatriate's most beloved work. Join Christopher Funderburg as gives a worthy film a thoughtful second chance - and maybe even comes out of the process as a newly-minted fan.

{AGAiNST AUTEURiSM: CAT PEOPLE

& CURSE OF THE DEMON}

{PiNK SMOKE PODCAST: BERLiN EXPRESS}

{NiGHT OF THE DEMON}

{THE MOViE SHELF: NiGHTFALL}

{the SECOND CHANCES index}

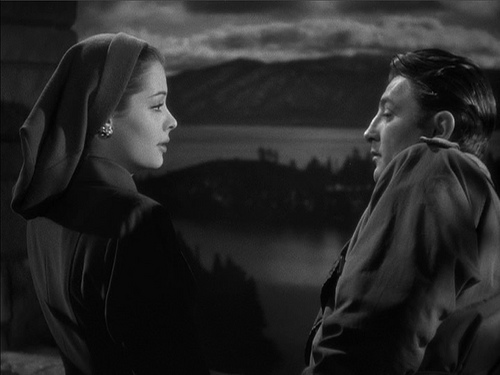

OUT OF THE PAST

jacques tourneur, 1947.

“My feelings? About ten years ago, I hid them

somewhere and haven’t been able to find them.”

You’re probably saying to yourself, “What kind of an asshole doesn’t like Out of the Past?” Robert Mitchum, Kirk Douglas, Jacques Tourneur, cinematographer Nicolas Musuraca, Jane Greer - this might be the film noir. Does any film noir - Double Indemnity, The Big Sleep, Laura - have a superior stake to being called the genre’s exemplar? More of a claim to being the grimy cream of a desperate black crop?

As with a lot of films we’ve covered in this series, it’s not that I dislike Out of the Past or think it’s a bad film, my reason for wanting to give it another shot is that people love but love this movie and I had a mild reaction to it. In general, the widest gulf between run-of-the-mill cinephiles and myself is that I don’t have much of an enthusiasm for a genre that a professed indifference towards is enough to get your license yanked.

I can’t figure it. I love crime films and novels, I consume a steady diet of Patricia Highsmith, Charles Willeford, George V. Higgins, Jim Thompson and Donald Westlake and their cinematic analogs; I constantly consume less gourmet concoctions of a similar kind as well. It’s genuinely puzzling why I don’t respond more to film noir. My own mind is a mystery to me. A shocking mystery to be unraveled through careful observation and street-savvy honesty about the human condition à la Simenon’s Magrit. There’s a void in my cinephiliac heart and I can’t help but stare into that abyss, trying to understand myself.

So here I am, selling you on this article as a bit of existential detective work - from that alone, shouldn’t the plaintive fatalism of film noir be inherently appealing to me? I don’t know why it isn’t. It might be that the titanic monuments of the genre, the Bogart films, the Billy Wilder films, don’t sink into my subconscious as profoundly as the more marginal curios like Nightmare Alley, Thieves Highway, Criss Cross and Gun Crazy.

It’s a genre that was defined post-facto with loose parameters so some of the time I’m surprised when brilliant films like Sweet Smell of Success, Gaslight, Brute Force or T-Men are even considered noir. If you shoved me down into a rusted metal chair under a naked bulb and went title by title, you’d probably end up forcing the confession that “Yes, I like The Naked City, yes I like Kiss of Death, yes I like The Woman in the Window, yes I like Raw Deal” and so on until you had enough hard evidence to convict me of being a film noir fan if not aficionado.

Maybe all it is, is that I’m working too hard to no clear end to define what makes a film noir - isn’t there a difference between a simple crime film like White Heat or The Killing and a noir? Between a Gothic melodrama like The Strange Loves of Martha Ivers or a shadowy spy film like The Third Man and the Platonic ideals of the genre? To love the genre, don’t I have to love the films that are unquestionably noir, films like Out of the Past? For the moment, all I can do is lock noir in a cold and desperate embrace, look deep in its eyes and wonder what it really is, what it really means.

THE SECOND CHANCE

Watching Out of the Past again for the first time in a decade, I can tell you that what I don’t respond to about the movie are the things that define the genre - Out of the Past is undoubtedly one of the essential noir masterpieces, but I’d like it more if it weren’t. It's a film shrouded in gorgeous shadows and cut open by hard angles of light, exactly the way a film noir should be. It's a film where the dialog's a razor sharpened by wit and cynicism, exactly the way a film noir should be. It's a film where a gumshoe in a raincoat and fedora doesn't believe a gorgeous woman no matter how her desperate eyes plead with him.

It's a film I find hard to believe because its story's too pat.

The plot couldn’t be more basic for noir: a brooding loner just wants to run his small-town gas station and be left alone. Right as things are getting serious with the young lass who just can’t quit him despite his murky past, a smooth-talking heel shows up and lets him know that somebody disquietingly important, the big man himself, has been looking for him for a long time and wants to see him. Just to talk.

From there, the story hops to a few more noir staples: a lengthy flashback about a doomed romance with an alluringly mysterious woman who might not be as innocent as she claims. Is this meeting with the big man about that woman? Yes - and the $40,000 she’s accused of making off with. It keeps going, adding more of the usual: blackmail, a panicked getaway, a double-cross, a midnight rendezvous, a frame-up, a murder in the heat of passion, a police roadblock and a vengeance-driven mute teenager armed with a fishing rod.

As the definition goes, noir plots weave a web of circumstances that only entangle our hero further as he thrashes about within them. Trying to escape only makes the situation more dire: turns keep getting worse until the audience can feel the doom clinging to him from head to foot, roping him in place. As a result, noir stories have a tendency to pile on incident after incident until there’s no way for things to get worse without relying on coincidences, narrative elisions and contrived motivations.

Out of the Past in particular can’t stop felting threads for its dooming web, it keeps introducing new characters with new malices through to the end of the film: a sweet small-town girlfriend, a jealous back-water cop, a menacing thug, a mysterious millionaire, a femme fatale, a double-crossing ex-partner, a shady lawyer and all of these conflicts feel only tangentially looped together, the jealous cop connected to the shady lawyer only by the flimsiest gossamer zig-zag across the expanse of the entanglement.

What makes the film feel like the essential noir is the way in which it uses every defining archetype of the genre to create its chaotic mesh. If you step back from it, the film can be taken in as a coherent whole not because of any deft organizing on the part of the script or the director, but because each thread hangs together naturally no matter how haphazardly they are interwoven. The plot works because it’s woven almost exclusively from the most autogenetic strands of the genre. Like a lot of films noir, Out of the Past has a compulsion to keep adding to its clingy net, to keep widening its expanse - but like only the best of the genre, its story feels both shamelessly contrived and bleakly inevitable.

It’s a perverse tone: the story is going where it's headed regardless of the contrivances used to drive it there. I guess that’s a close enough cousin to Aristotle’s maxim that any dramatic art should have a resolution that’s both inevitable and surprising.

When the film works - and let me be clear: going scene by scene, this film works - its success can be attributed to its casting. In what seems to be the natural order of things, the older I get, the more I’m into Robert Mitchum. Ten years ago, I wouldn’t have thought to mention him if you asked about my favorite actors, give me another ten and he’ll probably be the first one who comes to mind. In Out of the Past, he works his usual “drowsy dynamite” angle and it’s killer.

But Out of the Past has another ace in the hole with Kirk Douglas,1 still early enough in his career to be playing a villain with a relatively small amount of screen-time. He makes an impact - the producers must have felt like they struck gold in finding a performer with enough screen presence to not look silly in trying to wrest scenes from Mitchum's control, and even bully him here and there. It’s not a great part, or even a particularly interesting one, but once again: it’s archetypal. It’s the sort of villain that crops up over and over again in noir, where the pervasive sense of helplessness is frequently stoked by confrontations with men like this; men who are powerful enough to dominate your existence, obsessive enough to narrow their focus onto you and callow enough not to care what ultimately happens to you.

Kirk Douglas is a phenomenal actor who rarely seemed to be challenged by his roles. He’s great in Out of the Past but he also doesn’t seem to be working for it, he doesn’t take the part to any territory beyond where it’s routed to end up. This is both good and bad: he’s perfect, but he doesn’t exceed the limitations of that perfection. Menacing and suave, irresistible and nefarious, he’s everything the role calls for and nothing more. I repeatedly get the impression while watching his films that he’s an actor caught being flawlessly inconsequential.

It’s impossible not to contrast him to Mitchum’s loping, sleepy-eyed rhythms, the way Mitchum always seems to be wandering off course and taking the audience along with him through sheer effortless force of charisma. He’s a performer who exudes a desultory, impatient laziness, a guy who’s going to do his own thing the moment he gets bored - Tourneur sets him against the precision and focus of Douglas to brilliant effect.

Douglas’ Whit Sterling wants to dictate the circumstances of life to everyone around him: his hired thugs, his sleazy lawyer, Jane Greer’s Kathie Moffat,2 eventually Mitchum’s weary private eye. What seems to rankle Mitchum’s Jeff Bailey/Markham isn’t so much the implicit death threats as the impediment of his independence. Mitchum lets us know: this is a man who’d rather be fishing right now. Who’d rather not be in love with a gangster’s moll. Who’d rather not get his sweet young new girlfriend caught up in all this. Who’d rather not die, but that’s negotiable.

Mitchum is a performer who, without insisting, does what he will do. Douglas is a performer who, without embellishment, does what is required.

It’s perfect casting and it makes the film.

I’m less enamored of Jane Greer and that’s always the problem with a story like this: for the femme fatale to work, the audience has to fall for her as well. Forget the anklet, Double Indemnity plays because who the hell could resist Barbara Stanwyck? Watch Peggy Cummins doing trick-shots and it's not the guns that will make you crazy. Jane Greer is fine but to go crazy for Out of the Past, I’d have to go crazy for her.

It feels absurd to talk about needing to go head over heels for a character in order for a film to work, but that's what it is. Sure, cinema is a plastic image, an unreality, but with film noir the whole point is falling in love with the portrait of Laura and the stories you concocted in your head about her.

The betrayals of Out of the Past feel weightless to me in that context. It won’t break my heart, what happens with Kathie Moffat either way, so it’s hard to feel too bogged down in the desperation of it all. Mitchum plays nearly every character like he was born to die bleeding out in the back of a cab after being stabbed to death, answering the driver for where’s headed with a terse, “Nowhere, just drive.” You're not worried about Mitchum because Mitchum is doomed from the first frame; you’ve got to care what happens to Moffat, to worry that you’re a fool for caring, to search for the double-cross and curse yourself for doubting - that's the only way the film can hit at full force.

Greer stays at a distance from me, so Out of the Past stays at a distance. “All women are wonders, because they reduce all men to the obvious,” as the film says. I don’t feel reduced enough to the obvious with Out of the Past.3

None of this is to say that I don’t appreciate the film or think she lacks chemistry with Mitchum. Who could hate a film with this exchange:

Kathie: I don’t want to die.

Jeff: Neither do I, baby, but if I have to, I’m going to die last.

That’s the needle I’ve been trying to thread: I don't want to disparage a film that I admire. I don't want to disparage a genre and by default its exemplification. I’m trying to understand why I don’t connect with a formula that on the surface feels instinctively like something I should connect with.

I believe with a kind of dreamy sentimentality that romance is doomed, that fate conspires against us, that we can’t escape our failures, that there are malicious forces in the world beyond our control; I believe in a kind of inevitable pain to going on with it, day after day, that there’s no way to win, only to lose more slowly. It’s not that I’m repulsed that noir somehow commodifies or Hollywood-ifies these sentiments, either - there’s a tender (ah, fuckin' maudlin) quality to my sense of these things.

It’s tempting to tie this further to noir themes: the total mystery of why we love someone or not, of why we fall for the woman in the picture frame or not. But it feels pretty glib. I’d like to like this movie more than I do. I wonder why I don’t. Could it be as simple as swapping Barbara Stanwyck into the Jane Greer role? Or do I wish it would abandon its generic conventions and follow its story down stranger avenues? Usually, I admire Tourneur for his precision and restrained direction, but would I have preferred if this time he had employed a more fevered style?

All of these questions would feel absurd in the face of a perfect film. And how could a film that defines its genre be anything other than perfect?

~ APRiL 17, 2018 ~

1 Kirk Douglas was in a film called Ace in the Hole. This is a reference am I making and if you get the reference, you might be tempted to call it a “joke.” But it is not. There is no joke there.

2 What an awful name for a femme fatale.

3 And then some asshole says to me, he says, “I disagree, I read your review of the film!”

4 One more footnote, disconnected to anything in the article, this one’s for true footnote fanatics: another reason I watched this movie again is that Errol Morris is fond of quoting it. Morris uses the line “I could see the frame, but I couldn’t see the picture” when talking about the philosophical impetus of his “existential detective films.” I was shocked to find out that’s not the line! Mitchum says, “I think I’m in a frame… I don’t know. All I can see is the frame. I’m going in there now to look at the picture.” This doesn’t blow up Morris’ concept or anything, but since he quotes it so frequently I was surprised to see he had revised the line to slightly better suit his needs.