THE MOVIE SHELF: comparing films to their literary counterparts

NiGHTFALL

jacques tourneur, 1957.

All this month, The Pink Smoke will be delving into the inarguably excellent but strangely undervalued work of French-expatriate Jacques Tourneur. From his hand in creating the Platonic ideal of film noir with Out of the Past to redefining the horror genre by focusing on its psychological elements with Cat People, Tourneur's role in cinema history is substantial and (get this!) multifarious - so, why isn't his name uttered in the same breath as Howard Hawks, Tod Browning or even Edward G. Ulmer?

This next round in our Tourneurment is The Movie Shelf, an ongoing series that compares the films on our dvd shelves to the novels on our bookcases. It's "book versus movie" time, Tourneuriacs.

{AGAiNST AUTEURiSM: CAT PEOPLE

& CURSE OF THE DEMON}

{PiNK SMOKE PODCAST: BERLiN EXPRESS}

{SECOND CHANCES: OUT OF THE PAST}

{NiGHT OF THE DEMON}

{the MOViE SHELF index}

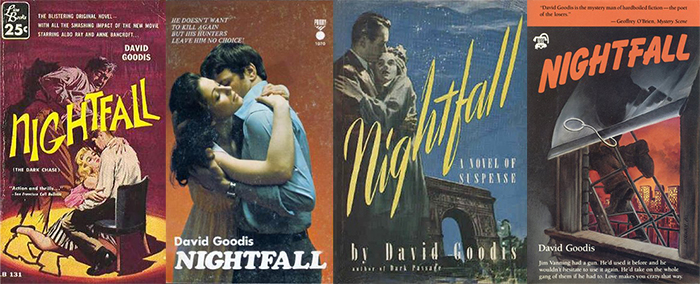

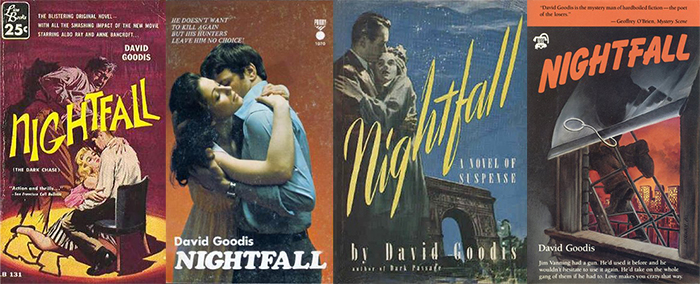

based on the novel

NiGHTFALL

david goodis, 1947.

“It was such a miserable state of affairs that it was almost comical.”

~ by christopher funderburg ~

When writing these Movie Shelf pieces, I have a tendency to at some point eventually get around to fawning over a performance that brings something unexpected to a character, an actor who transforms and expands what’s on the page in a way that’s striking and essentially cinematic.

With Nightfall, I don’t want to wait to get around to it:

Anne Bancroft is a magnificent actor.

In Jacques Tourneur’s adaptation of David Goodis’ dime-store crime story, Bancroft plays a young woman who, as she is written in the novel, I would be hard pressed to characterize as anything other than “some lady.” Late in the book, after a series of intense reversals of fortune and life-or-death situations that manage to reveal almost nothing about her, the protagonist describes her this way, “She’s such a healthy girl, she’s full of living. She needs a guy. She needs a home. And kids.” I can’t think of a single meaningful characteristic with which to describe her or a notable line of dialog she’s given in the book, I couldn’t offer a coherent explanation of her motivations or imagine much of a backstory for Goodis' character.

It’s the definition of a thankless role.

Tourneur and screenwriter Stirling Silliphant flesh out the character somewhat, but not far beyond the kind of striking archetypes Silliphant employed in his TV shows Route 66 and Naked City. The film relocates the action from New York City to Los Angeles, but the filmmakers at least turn “Martha Gardner” into an identifiable type of New Yorker: a savvy, tough-talking fashionista.1

In the book, nothing about the character’s relationship to the begotched hero even skips across the plane of believability. In the film, her cosmopolitan world-weariness makes it plausible that she might abscond to the countryside with a man she barely knows.

But Anne Bancroft... ah, Anne Bancroft. Anything she tells me, I believe.

Of all the finest actors to come out of the method school - Marlon Brando, Gene Hackman, Warren Beatty, Robert DeNiro - Bancroft’s reputation is the most unquestionably out of whack with her talent level. It’s impossible to see her in Nightfall, playing an absurdly thin part, and not understand why early in her career she fled Hollywood for Broadway. What appeal could there be for an actor to play underwritten dames who are called upon to do nothing but offer support and companionship for ruddy rubes like Aldo Ray’s “Jim Vanning?”

She appeared in 15 films between 1952 and 1957 and you’d have to be some kind of an asshole to describe any of them as “a great character, a really great part” - some of these roles, like a scheming circus-performer in a low budget, low stakes, low intelligence, King Kong knock-off called Gorilla at Large make me sad to even think about.2 Even Nightfall, which is a great film in which she gives a great performance, the role isn’t worth her time, not really. An actor so talented is owed better characters, better writing, than her collaborators gave her to work with. The role is explosive because Bancroft is dynamite in it - not vice versa. Is it any wonder she wanted to give up on tight dresses and acidic one-liners and go across the country to, you know, act?

After conquering The Great White Way (this is a nickname for Broadway which is a street in Manhattan which is a metonym for the professional theater circuit located around a section of that street), Bancroft returned to Hollywood to deliver jaw-dropping performances in 1962's The Miracle Worker and 1964's The Pumpkin Eater. It’s not a coincidence that both films are adaptations of theater pieces. But just as quickly she found herself typecast again, this time as cinema’s premier predatory cougar, after her turn in 1967's The Graduate.

So she receded from Hollywood once again, mainly turning up in roles for her husband Mel Brooks - playing herself in Silent Movie, co-starring in To Be or Not to Be, taking on a key role in Brooksfilm’s The Elephant Man. In the mid-80’s, she had a nice run with Agnes of God, 84 Charing Cross Road and ‘night, Mother but her days as a lead were behind her and by the early 90’s she had settled into the life of character actor. She had a slew of roles in films like Honeymoon in Vegas, Home for the Holidays and Love Potion No. 9 that are in their own way as dispiriting as her initial work as an ingenue.

It’s telling that late in her career filmmakers couldn’t decide whether she was better suited to “living legend makes a cameo” roles or “sympathetic authority figure” parts like doctors, nurses and senators that are usually reserved for talented actors who aren’t famous enough to be distracting in important but nevertheless throwaway parts. By that point, when she did get the chance to share the screen with commensurately talented actors like Gene Hackman, Ed Norton and Sigourney Weaver,3 it was bit parts in charmless flops designed to launch “stars” like Jennifer Love Hewitt or Jenna Elfman.

In Nightfall, she reveals herself to be an amazingly precise and inventive performer. Midway through the film, when Jim Vanning is still trying to work out whether she’s conning him or not, he accuses her of working with the bank robbers who are hot on his tail. Her reaction contains a half-dozen gestures in a single shot, some subtle, some forceful - it’s an amazingly expressive moment, one with more good work by Bancroft in a matter seconds than some performers orchestrate in a lifetime.

The eveness of her voice as she asks "Do you always answer your own questions?" a counterpoint to the anger that flashes in her eyes - she bows her head to regroup, wanting to project her anger outward, but strictly under her control. Her hair is up for the night, she's stripped of make-up, there's an incredible lack of vanity in her work in this moment - method acting is rightfully associated with a showiness that frequently takes on an off-puttingly contrived quality, actors reveling in their own acting; the ultimate performer's vanity. There's none of this in Bancroft's work, it's delicate and unbreakable, butterfly wings with veins of steel.

It’s impossible to imagine Nightfall being as good as it is without Bancroft - and if there weren’t the film up there on the screen to prove, it would be just as hard to imagine that a good film could be made from David Goodis’ terrible novel. That’s a striking contrast because you’re more likely to hear Goodis’ name in the context of Nightfall’s greatness than Bancroft’s.

Goodis is known to cinephiles for having written Down There, the film adapted by François Truffaut into Shoot the Piano Player. That it’s a famously loose adaptation has done little to impede the novelist’s name from becoming somewhat sacrosanct to a certain portion of more knowledgeable filmgoers. Tourneur’s brilliant Nightfall is usually the second exhibit in any case that Goodis should be revered, but like Down There the book is virtually unreadable and every good idea comes from the filmmakers.

What’s so strange about Goodis’ Nightfall is that film noir has tendency to hang itself on great hooks: I have 24 hours to find out who killed me before a slow-acting poison does me in, if two strangers on a train trade murders they’ll never be caught, my husband’s life insurance policy has a clause that doubles the payout if he dies under the right circumstances, a detective becomes so obsessed with a murder case he falls in love with the deceased victim.4

There’s no hook to Nightfall, not really. Apropos of Tourneur’s involvement, it has a similar set-up to Out of the Past, this time with some rubicund square named James Jimmy-Jim Vanning getting drawn back into a criminal past he wants nothing to do with. But the set-up in the book is absurd: a trio of bank robbers fleeing Seattle get into an accident on a twisty mountain road just outside of Denver. Vanning, a good samaritan, pulls over to help them: one of the gangsters is in dire need of medical attention and the police (in Seattle?) are on the lookout for their vehicle so they commandeer Vanning’s sedan and force him at gunpoint to play wheelman.

From there, they take the heavily injured hoodlum to a shady doctor before heading off to hole up for the night in a cheap motel. They tell Vanning to go sit in the bathroom, using the hotel commode as a makeshift prison cell. He listens and after it seems like the two remaining bank robbers have left, he exits the bathroom.

There’s a gun on the bed? And the satchel full of money is still there, too?

He takes the gun, he takes the money, he scrams and before he can even get out of the motel’s parking lot, he’s approached by a shifty mobster, a whole new guy who we’ve never seen before and who has no clear relationship to the fugitive heisters. After some aimless chit-chat, this fresh new hood quickly reveals himself to be a hitman by attempting to shoot Vanning in an alley near the hotel - but Jim (despite being just some guy) is too quick on the draw and out-duels the professional killer who had the drop on him.

From there, Vanning runs away and, I shit you not, he... loses the money. He just drops it somewhere. He can’t remember.

At one point he stops running through the mountainside, looks down at his hands and basically says to himself, “Wasn’t I carrying something?” He doesn’t even remember losing it, where he might have lost it, there’s no scene where he slips on the ice and the satchel flies open sending the money fluttering away over a cliff. Goodis portrays the incident more or less like Vanning thinking, “Oh shit, didn’t I have some money? That really sucks because I’m sure not where I am so I'll never be able to recover it. And it was a lot of money - I'd bet those gangsters will want it back!”

One the funniest aspects of the book, maybe the only thing that I might be tempted to call its hook, is that everyone he encounters thinks his story of simply having lost the satchel is ridiculous. How could thousands of dollars slipping away have just slipped his mind? The gangsters, the insurance investigator, even the love interest, all have a reaction of, “No, but seriously, where’s the money? You obviously didn’t lose it.” Vanning’s whole reason for avoiding the cops (who link him to crimes almost immediately) is that he doesn’t think they’ll believe him about any of this shit.

If Goodis were a better writer, the nightmarishness of this angle is something you could work with - but if the convoluted summary doesn’t make it clear, he just seems to be making things up as he goes along. It’s a book that feels deeply, hopelessly aimless. What’s the #1 action Vanning takes over and over again in the book? What does he do when circumstances now more than ever dictate that he must respond? He goes and gets some sleep.

Worried someone is tailing you around Greenwich Village? Time to get some sleep.

Just escaped from mobsters who were torturing you in a Brooklyn warehouse? Time for a little shut-eye.

Worried the woman you’ve chosen to trust you might betray you? Let’s hit the hay, I’m beat.

The only way I can figure it, Goodis must've been very sleepy when he wrote this novel.5 The lack of urgency in this book is incredible: every time it seems like it should be gearing up, Vanning heads home to either take a nap or work on some of the drawings he needs to do for his day-job as a commercial artist. Even when there are only a couple dozen pages left in the book, he’s still wandering away from the story to catch some Zzz’s.

Not only that, the book is also frustratingly talky, the final climax is a series of conversations where various parties are held at gun-point as the situation gets talked through. Throughout the novel, everybody constantly tries to suss out the implications of every situation: Vanning with Martha, Vanning with the gangsters, the insurance investigator Fraser with his wife, Vanning with Fraser, Fraser with Martha, Martha and Fraser with the gangsters. Everybody talks with everybody else about whom is potentially double-crossing whom and what may have really happened when and the likely outcomes given what they know.

Even when Vanning is all alone making his escape from the hotel bathroom-prison-cell, he wants to hash it out with someone. “Maybe if he laughed loud enough, someone would come in and see him here and talk to him. He wanted that badly right now. If he only had someone in here with him, someone with whom he could discuss this.” There’s almost no story to the book: the story is the story of people discussing the story, at length, ad nauseum, ad infinitum, addled.

After icing the ol' hitman, losing the money and dodging the cops, Vanning absconds across the country to New York City and settles into a mundane life as an commercial artist, but the novel is structured around flashbacks, so the book begins with Vanning already on the East Coast before jumping in and out of different points in the narrative. Goodis frequently switches up tenses to a disorienting effect as the story slips around its timeline - the only thing the book has going for it is how well Goodis handles the nebulous structure.

But ultimately, the vague timeline seems to be a cover for the inexplicable fact that both the bank robbers and an insurance investigator employed by the bank have caught up to Vanning in NYC. There’s no good explanation for how either of them found Vanning living under his assumed identity and the games with the timeline allow Goodis to get away with some sleight of hand in that regard: he begins with these men having already caught up with Vanning; Goodis skips around to explain why they’re after him and how he got to New York but the writer can leave out the tricky business of dealing with how they caught up with him.

There are two things that the preceding summary belies: First, Martha Gardener is truly inconsequential to the story. Vanning thinks she set him up for the gangsters to get the drop, but it turns out not to be true. She’s an indescribably average young woman and it never once makes sense when she starts training pistols on captive gangsters while Vanning and Fraser head out into the night. Second, Tourneur and Silliphant are right to throw out almost all of that mess in order to make their film.

The filmmakers engage in a series of moves to streamline the plot and revise the key scenes. They eliminate one of the bank robbers. There’s no trip to the shady doctor, no motel, no on-call contract killer. With the bank robbers, instead of two generic thugs and their more reasonable boss, there’s a dumb mean one and a well-dressed co-conspirator who appears to be in charge. The more debonaire of the duo grows increasingly violence-averse as the film wears on and his weakness of will becomes apparent - his grasp on his authority over his gregariously vicious accomplice slips away as a result. In the book, it’s strictly a pair of knuckle-dragging leg-breakers and their “I’m talking reeaaaal nice in order to be scarier” boss.

By eliminating the hitman, Tourneur and Silliphant rightly judge that Vanning’s refusal to go to the cops will never have a fully convincing explanation. They lean into the irrationality of the decision - by contrast, Goodis seems to be piling on reasons for why Vanning absolutely cannot get law enforcement involved. Not only did he lose the money (the proof of his story), but he committed a murder in cold blood! What’s weird is that in the book, law enforcement still connects him to the bank robbers - Goodis writes himself into a corner where the money both matters to Vanning’s decisions and doesn’t matter. It’s a book where someone literally forgets to bring along the MacGuffin.

Tourneur and Silliphant instead position Vanning as an average Joe desperate to return to a normal routine after his life was blown apart by a moment of panic. The casting of Aldo Ray is perfect - he excelled at playing All-American lugs who are in over their heads but can’t admit it. His raspy, choked cadences make his every word sound like a man who can barely get through a sentence - the basics of existence are taxing to him. Blonde, baby-faced, red-cheeked, beefy and strapping, he’s a mess of perfectly American contradictions like excessive confidence, naiveté, confusion and self-reliant can-do spirit.

He makes for a ridiculous pairing with Bancroft’s dark-browed urbanity, an overtly sexy and cerebral Italian model from the Bronx paired up with a sweetly blustering, corn-pone lug - but it’s easy to see what appeals to her about his bull-in-a-china-shop guileless charms and Bancroft is of course utterly irresistible for her part. They’re a weird match that’s great - the adventure and exoticism of their bond instantly clicks into place. I also suspect that Anne Bancroft could generate onscreen chemistry with a tomato can.

Aldo Ray is pretty close to a human tomato can.

Tourneur and Silliphant reorganize the setting from the novel’s Seattle-Denver-New York jumble to the more evocative and logical Seattle-Wyoming-Los Angeles grouping. Silliphant’s sense of the American landscape that provided Route 66’s reason for being is put to great use by Nightfall and Tourneur. The snowy expanses of Wyoming during winter are gorgeous and terrifying; breath-taking expanses of empty whiteness bordered by the dark glow of the distant mountains. It’s one of the most outstanding examples of work in the oxymoronic sub-genre of “daylight noir.”

There's nowhere to run to - and it would take you an eternity to get there.

Wyoming’s unforgiving countryside contrasts brilliantly with the seedy neon of Los Angeles, Tourneur presenting the city as the perfect image of the cheapness and corruption of civilized existence - you get the sense Bancroft’s character doesn’t care so much about gangsters, lost money or even romance so much as seizing the opportunity to put on a nice, warm, stylish hunting jacket and explore the snowy vistas of the American pastoral. Los Angeles is all dive-bars, loneliness and unappealing strangers bumming cigarettes. Wyoming is deadly isolation and the awe-inspiring pitilessness of nature.

By contrast, the novel’s climax takes place in a generic one-bedroom apartment.

Silliphant’s sense of location can even be found in smaller locations changes. In the book, the gangsters find Vanning in New York and rough him up in a warehouse. What kind of warehouse? Who knows. In the film, he’s dragged to the oil fields on the edge of the city - a wooden 2-by-4 is shattered by the cycling derrick in a demonstration of what’s in store for Vanning’s shin if he doesn’t cough up the location of the dough. The dispiriting cruddiness of L.A. is even a factor in convincing the insurance investigator that Vanning wasn’t in on the bank robbery: no one would live where Vanning does if he had any money.

This is one of Silliphant’s greatest strengths, the simple understanding that setting itself can give a scene a compelling focus and energy: by switching yet another scene set in a generic apartment to a runway show (the hoods bust in and disrupt the whole thing), the script can begin amassing clever and interesting details. Look at the way Vanning sweeps Marie Gardener off her feet during the escape: she’s wearing an evening gown and high heels, she can’t run so he’s got to grab her like a groom sweeping up his bride. It’s an intense and romantic detail derived entirely from the switch in setting.6

There’s a hundred little changes the filmmakers make from the novel. But it’s tough to say to say they betrayed the book or used it only as a suggestion for something else entirely - compare it to Shoot the Piano Player in that regard, which uses the novel as a springboard for playful, semi-ironic Nouvelle Vague experimentation. It might be better to say with Nightfall that the filmmakers guided their artwork away from the novel, that they somehow took the story and led it by the hand where it always wanted it to go (but Goodis had failed to take it.)

So let me close the loop: you should be including Bancroft in your mental role-call of Nightfall’s guiding artists. It’s impossible to imagine Nightfall being Nightfall without her work, without her performative creation. She doesn’t dominate the movie - I think of Neil Jordan talking about how Bob Hoskins is Mona Lisa, she doesn’t take over the film that way - but she contributes something meaningful and major that does not and could not exist in the book. A performance like Bancroft’s is an essentially cinematic thing; the closeness and subtlety of her work is something that I’m unconvinced could be reproduced even on the stage.

In my introductory piece to Tourneur month, I wrote about the idea that it frequently makes sense to see a film as being a harmony of creative voices rather than the result of a single author’s insistences. That’s certainly the case with Nightfall where the artistic voices of Bancroft, Tournuer and Silliphant can be clearly heard. Can I hear Goodis’ voice in the film? That, I’m less sure about. Is there a point at which the conventions of a genre drown out an artist’s voice? Do I hear Goodis or just dime-store conventions? Or am I trying to ignore his voice because of its disharmony, the ways in which it is off-beat and out of key, drab and mundane and flat.

If I’m writing it down, I should have a decisive answer. But I don’t. Maybe that only proves my point: you can’t unthread these things the way everyone presumes to do. Tourneur, Bancroft, Silliphant, Goodis, Aldo Ray, everyone together, the better and the worse, is called Nightfall and that might be as finely as you can tune it.

~ APRiL 10, 2018 ~

1 I’m sure much to Superman and Batman’s chagrin, they also change her name from the homely and wholesome “Martha” to the less matronly “Marie.” Not that Marie is some fuckin’ exciting name, but it does conjure the Catholic ethnicities and tie the character to Italian and Latino cultures associated at the time with city living.

2 Look, I know the film has a cult reputation, what with its judo murders, secret gorilla suits and trapeze mayhem, but it must really suck to be a performer of Bancroft’s caliber stuck doing that kind of shit. That she always put the her best face forward and brought her talent and craft to these kind of roles isn’t a point the film’s favor, only Bancroft’s.

3 Truthfully, I don’t think those actors are anywhere near as talented as her. Nah, not even Hackman.

4 The other option is building them around a character, the character is the hook: Philip Marlowe, Sam Spade, Tom Ripley - Nightfall obviously lacks that kind of centering focus as well. Jim Vanning ain’t shit. Also, if you're curious, the films I’ve just described are The Man Who Knew He Had Been Poisoned, Strange Trainers, Doubly Devious (tagline: "Double the Devious, Double the Payout!") and Inspector Necrophile.

5 It all reminds me of the late Paul Cooney’s description of Fleming’s The Spy Who Loved Me.

6 I use the phrase “switch in setting” loosely here, there’s not a one-to-one analog for a lot of these scenes. The novel’s story is both convoluted and empty, so a lot of sequences get transformed into something else entirely (like the entire bit about Vanning believing the police think he’s a peeping tom because the insurance investigator caught him climbing a tree to peer in Martha Gardner’s window to see if she’s actually conspiring with the bank robbers at the exact moment one of them had showed up to shake her down so she was making that guy a cocktail to calm everyone down but to Vanning it looked like they were in cahoots so he naturally talks his way out of an arrest and goes home to get some sleep. Goddamn this book sucks.)